| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Daniela Morato, MD | Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Angeles, CA |

| Sean Henderson, MD | Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Angeles, CA |

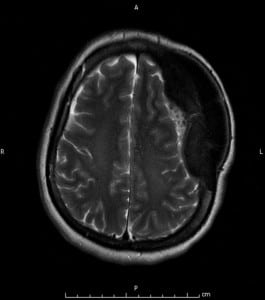

A 47-year-old Hispanic woman presented to the emergency department for evaluation of a left frontal head mass she reported noticing in the previous month, which caused her localized dull discomfort. She denied any recent or past trauma, and denied any vision, speech, motor or sensory changes. Her examination was significant for a large, firm, non-tender exophytic left frontal mass, approximately 5 cm in diameter with normal scalp overlying it. Her neurological examination was completely normal. An MRI revealed a 10x6x4 cm area of expansion of the left frontal and parietal calvarium with a plaque-like dural based mass underlying the calvarial thickening, consistent with a meningioma with interosseous extension. There was moderate mass effect on the underlying left cerebral hemisphere with a 5mm midline shift to the right (Figure 1).

Meningiomas are one of the most frequently reported primary intracranial neoplasm, accounting for approximately 25% of all such lesions diagnosed in the United States.1 The incidence increases with age and is higher in women, with a male-to-female ratio of about 1:2.2 While the majority (>90%) of meningiomas are histopathologically benign, they can be associated with devastating neurological complications, such as seizures and vision loss.3 The risk factors most commonly attributed to meningiomas are exposure to ionizing radiation and hormones, although the exact association between these has not been clearly defined.1 The options for management and prognosis of benign meningiomas are dictated primarily by tumor location and size. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment but given that these are slow-growing tumors and sometimes asymptomatic, it is not necessary for every patient. Other options include radiation alone or as an adjuvant to surgery, or observation.4

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Rick A. McPheeters, DO

Submission history: Submitted July 25, 2009; Revision Received November 29, 2009; Accepted January 11, 2010

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Sean O. Henderson, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, LAC+USC Medical Center, Unit #1, Room 1011, 1200 N. State Street, Los Angeles, CA 90033

Email: sohender@usc.edu

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Claus EB, Bondy ML, Schildkraut JM, et al. Epidemiology of intracranial meningioma.Neurosurgery. 2005;57:1088–95. [PubMed]

2. Rohringer M, Sutherland GR, Louw DF, et al. Incidence and clinicopathological features of meningioma. J Neurosurg. 1989;71:665–72. [PubMed]

3. Feun LG, Raub WA, Landy HJ, et al. Retrospective epidemiologic analysis of patients diagnosed with intracranial meningioma from 1977 to 1990 at the Jackson memorial hospital, Sylvester comprehensive cancer center: the Jackson memorial hospital tumor registry experience. Cancer Detect Prev. 1996;20:166–70. [PubMed]

4. Lee JH, Sade B. Management options and surgical principles. In: Lee JH, editor. Meningiomas: diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. London: Springer; 2009. pp. 203–207.