| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Janet S Richmond, MSW | Tufts University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, Boston, Massachusetts |

| Jon S Berlin, MD | Medical College of Wisconsin, Departments of Psychiatry and Emergency Medicine, Milwaukee, Wisconsin |

| Avrim B Fishkind, MD | JSA Health Telepsychiatry, LLC, Houston, Texas |

| Garland H Holloman, Jr, MD, PhD | University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry, Jackson, Mississippi |

| Scott L Zeller, MD | Alameda County Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry, Oakland, California |

| Michael P Wilson, MD, PhD | UC San Diego Health System, Department of Emergency Medicine, San Diego, California |

| Muhamad Aly Rifai, MD, CPE | Drexel University/Blue Mountain Health System, Department of Psychiatry, Lehighton, Pennsylvania |

| Anthony T Ng, MD, FAPA | Acadia Hospital, Bangor, Maine |

ABSTRACT

Agitation is an acute behavioral emergency requiring immediate intervention. Traditional methods of treating agitated patients, ie, routine restraints and involuntary medication, have been replaced with a much greater emphasis on a noncoercive approach. Experienced practitioners have found that if such interventions are undertaken with genuine commitment, successful outcomes can occur far more often than previously thought possible. In the new paradigm, a 3-step approach is used. First, the patient is verbally engaged; then a collaborative relationship is established; and, finally, the patient is verbally de-escalated out of the agitated state. Verbal de-escalation is usually the key to engaging the patient and helping him become an active partner in his evaluation and treatment; although, we also recognize that in some cases nonverbal approaches, such as voluntary medication and environment planning, are also important. When working with an agitated patient, there are 4 main objectives: (1) ensure the safety of the patient, staff, and others in the area; (2) help the patient manage his emotions and distress and maintain or regain control of his behavior; (3) avoid the use of restraint when at all possible; and (4) avoid coercive interventions that escalate agitation. The authors detail the proper foundations for appropriate training for de-escalation and provide intervention guidelines, using the “10 domains of de-escalation.”

INTRODUCTION

Traditional methods of treating agitated patients, ie, routine restraints and involuntary medication, have been replaced with a much greater emphasis on a noncoercive approach. Experienced practitioners have found that if such interventions are undertaken with genuine commitment, successful outcomes can occur far more often than previously thought possible. In the new paradigm, a 3-step approach is used. First, the patient is verbally engaged; then a collaborative relationship is established; and, finally, the patient is verbally de-escalated out of the agitated state. In some ways, this is a return to Lazare’s methods published in an article written more than 35 years ago.1

The traditional goal of “calming the patient” often has a dominant-submissive connotation, while the contemporary goal of “helping the patient calm himself” is more collaborative. The act of verbally de-escalating a patient is therefore a form of treatment in which the patient is enabled to rapidly develop his own internal locus of control.

When working with an agitated patient, there are 4 main objectives: (1) ensure the safety of the patient, staff, and others in the area; (2) help the patient manage his emotions and distress and maintain or regain control of his behavior; (3) avoid the use of restraint when at all possible; and (4) avoid coercive interventions that escalate agitation.

These objectives may be challenging to pursue in some situations and settings. For example, in an emergency department, both the clinician and patient can slip into irrational thinking or expediency at the price of engaging each other. A clinician who has many patients to see and too little time may prematurely use medication to avoid verbal engagement. However, using medication too quickly may seem dismissive, rejecting, or humiliating to the patient2 and can lead to more agitation and violence.

Agitation is a behavioral syndrome that may be connected to different underlying emotions. Associated motor activity is usually repetitive and non–goal directed and may include such behaviors as foot tapping, hand wringing, hair pulling, and fiddling with clothes or other objects. Repetitive thoughts are exhibited by vocalizations such as, “I’ve got to get out of here. I’ve got to get out of here.”3 Irritability and heightened responsiveness to stimuli may be present,4 but the association of agitation and aggression has not been clearly established.5

Agitation exists on a continuum, eg, from anxiety to high anxiety, to agitation, to aggression.6 The agitated patient may be unable to engage in any conversation, and may be on the edge of new or repeated violence, requiring vastly different management than a person who may be willing and able to engage. The Project BETA (Best practices in Evaluation and Treatment of Agitation) guidelines7discussed in this section will help shape a practical, noncoercive approach to de-escalating agitated patients regardless of etiology or capacity to engage in a therapeutic relationship.

CLINICIAN’S APPROACH TO AGITATION

Emergency psychiatry is a well-established mental health discipline. However, the number of emergency psychiatrists and the volume of psychiatric crises they see are limited when compared to the number of emergency department physicians evaluating psychiatric emergencies. Interventions must often proceed with the agitated patient with, at best, a tentative diagnosis.

A paradigm that can be useful for both psychiatrists and emergency physicians is one in which the clinician uses rapid assessment and decision-making skills in an effort to quickly provide symptom relief. This relief, through verbal de-escalation and/or medication, enhances a positive clinician-patient relationship, decreases the likelihood of restraints, seclusion, and hospital admissions,8 and prevents longer hospitalization, since the use of restraints has been associated with increased length of stay.9,10 After initial stabilization of the patient’s agitation, the clinician can work with the patient to establish a final diagnosis.

Regardless of underlying etiology, agitation is an acute emergency and “requires immediate intervention to control symptoms and decrease the risk of injury” to the patient or others.11 While voluntary medication and environment planning are also important, verbal de-escalation and nonverbal communication are usually key to engaging the patient and helping him become an active partner in de-escalation.

Finally, each clinician must remember the 4 main reasons for using noncoercive de-escalation. First, when staff members physically intervene to subdue a patient, it tends to reinforce the patient’s idea that violence is necessary to resolve conflict. As such, noncoercive de-escalation is a success for the patient and staff, and is in effect a form of treatment. Second, patients who are put in restraints are more likely to be admitted to a psychiatric hospital8 and have longer inpatient lengths of stay.9,10Third, the Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services consider low restraint rates a key quality indicator, and fourth, staff and patients are less likely to get hurt when physical confrontation is averted.

DE-ESCALATION OF AGITATED PATIENTS IN THE EMERGENCY SETTING

General principles of verbal de-escalation can be found in specific psychotherapies, linguistic science, law enforcement, martial arts, and the nursing profession. Clinicians who work with agitated patients on a daily basis have perfected skills that frequently are in line with principles found in these resources. However, a review of the literature indicates that scientific studies and medical writings on verbal de-escalation are few and lack descriptions of specific techniques and efficacy.

There is indirect evidence from pharmacologic studies of agitation that verbal techniques can be successful in a substantial percentage of patients. In a recent study, patients were excluded from a clinical trial of droperidol if they were successfully managed with verbal de-escalation; however, the specific verbal de-escalation techniques were not identified or studied.12

The following guidelines were therefore developed by the consensus of the authors and a review of the limited available literature on verbal de-escalation.13–15

GUIDELINES FOR ENVIRONMENT, PEOPLE, PREPAREDNESS

Guideline: Physical Space Should Be Designed for Safety

The physical environment is important for the safe management of the agitated patient. Moveable furniture allows for flexible and equal access to exits for both patient and staff. The ability to quickly remove furniture from the area can expedite the creation of a safe environment. Some emergency departments prefer stationary furniture, so that the patient cannot use the objects as weapons, but this may create a false sense of security. There should be adequate exits, and extremes in sound, wall color, and temperature of the environment should be avoided to minimize abrasive sensory stimulation. Be mindful, also, of the potential for an agitated patient’s throwing objects that may cause injuries to others. Any objects, such as pens, sharp objects, table lamps, etc that may be used as weapons should be removed or secured. The clinician should closely monitor any objects that cannot be removed.

Guideline: Staff Should Be Appropriate for the Job

Clinicians who work in acute care settings must be good multitaskers and tolerate rapidly changing patient priorities. In this environment, tolerating and even enjoying dealing with agitated patients takes a certain temperament, and all clinicians are encouraged to assess their temperament for this work.

Agitated patients can be provocative and may challenge the authority, competence, or credentials of the clinician. Some patients, in order to deflect their own sense of vulnerability, are exquisitely sensitive in detecting the clinician’s vulnerability and focusing on it. To work well with agitated patients, staff members must be able to recognize and control countertransference issues and their own negative reactions. These include the clinician’s understanding of his own vulnerabilities, tendencies to retaliate, argue, or otherwise become defensive and “act-in” with the patient. Such behaviors on the part of the clinician only serve to worsen the situation. Clinicians need to also recognize their limits in dealing with an agitated patient, as it can be quite taxing, and sometimes the best intervention is knowing when to seek additional help.

Security and police officers, who work with agitated patients, must accept that a patient’s abnormal behavior is a manifestation of mental illness and that de-escalation is the preferred treatment of choice. The Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) model is a police-based, first-responder program that has been implemented nationwide. Persons taken into custody because of suspected mental illness are taken to a psychiatric emergency service or other facility where the person can receive psychiatric evaluation and treatment. CIT officers usually volunteer for these teams so that an officer is not forced into taking on a role that he does not want. Training of officers is provided by mental health professionals, legal experts, and advocates.16,17

Natural skill at verbal de-escalation exists on a continuum. However, almost anyone can learn de-escalation techniques and use them successfully if he is well trained and adopts a certain skill set. The most essential skill is a good attitude, starting with positive regard for the patient and the capacity for empathy. Staff should be able to recognize that the patient is doing the best he can under the circumstances, ie, the patient is experiencing difficulty in conforming to what is expected of him. Clinicians in emergency settings also will need to be skilled at recognizing that the inability to conform is due to either cognitive impairment—for example, delirium, psychosis, intoxication, and intellectual disability—or the patient’s lack of the skills needed to effectively get his needs met, eg, personality disorder.

Guideline: Staff Must Be Adequately Trained

Training in management of the agitated patient decreases the tendency of clinicians to avoid working with these patients. The American Psychiatric Association Task Force on Psychiatric Emergency Services18 has recommended that staff receive annual training on managing behavioral emergencies. This training is analogous to advanced cardiovascular life support training, ie, knowledge about skills can be taught in a classroom or can be learned from a book, but skills come only with practice. De-escalation skills can be learned by role playing and can be practiced in day-by-day encounters with nonagitated patients who are considered to be difficult in the sense of not conforming to what the clinician expects.

All persons who work with agitated patients should receive training in de-escalation techniques. A person, who is appropriate for the job, as discussed earlier, should be the one who works directly with the patient. A psychiatrist, emergency physician, or any other healthcare worker can become proficient at de-escalation, and any of these can engage the patient and perform de-escalation.

De-escalation frequently takes the form of a verbal loop in which the clinician listens to the patient, finds a way to respond that agrees with or validates the patient’s position, and then states what he wants the patient to do, eg, accept medication, sit down, etc. The loop repeats as the clinician listens again to the patient’s response.19 The clinician may have to repeat his message a dozen or more times before it is heard by the patient. Yet, beginning residents, and other inexperienced clinicians, tend to give up after a brief attempt to engage the patient, reporting that the patient won’t listen or won’t cooperate.20

The amount of time permitted for verbal de-escalation may vary depending on the setting and other constraints. However, it is the consensus of Project BETA De-escalation Workgroup members that verbal de-escalation frequently can be successful in less than 5 minutes. Its potential advantages in safety, outcome, and patient satisfaction indicate it should be attempted in the vast majority of agitation situations, even in very busy emergency settings.

Even the most complicated cases can be managed with a little additional time. Assuming that a single interaction of listening and responding takes less than a minute, then a dozen repetitions of the clinician’s message would take 10 minutes at the most. De-escalation, when effective, can avoid the need for restraint. Taking the time to de-escalate the patient and working with him as he settles down can be much less time-consuming than placing him in restraints, which requires additional resources once he is restrained.

There are patients who cannot be effectively engaged and verbally de-escalated, eg, a delirious patient. However, training should emphasize that a patient may not respond to initial efforts to engage him in de-escalation and that persistence is indicated, especially when the patient is not showing signs of further escalation that is moving toward violence.

Guideline: An Adequate Number of Trained Staff Must Be Available

Working with an agitated patient is a team effort and there must be an adequate number of people to provide for verbal de-escalation, offer the possibility of voluntary medication, and maintain safety if the patient’s agitation escalates to violence. There is also a benefit in having enough people to provide a nonverbal communication to the patient that violence on the part of the patient will not be acceptable behavior. In a busy emergency service, the de-escalation team should consist of 4 to 6 team members made up of nurses, clinicians, technicians, and police and security officers, if available.

Guideline: Use Objective Scales to Assess Agitation

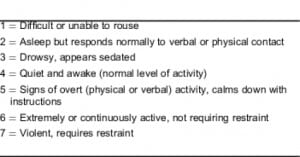

The use of objective scales to measure agitation can help mitigate defensive behaviors on the part of staff that might result in their avoiding or “ignoring” early signs of agitation. One such scale that is quite simple and easy to implement is the Behavioural Activity Rating Scale (BARS; Table 1).21

The initial BARS score should be based not only on the patient’s presentation, but also on his behavior before arrival at the emergency facility. Any score other than a 4 should trigger an evaluation by a clinician and establish the urgency of that evaluation. Other available scales include the Overt Aggression Scale,22 the Scale for the Assessment of Aggressive and Agitated Behaviors,23and the Staff Observation Aggression Scale.24

GENERAL DE-ESCALATION GUIDELINES

Guideline: Clinicians Should Self-Monitor and Feel Safe When Approaching the Patient

A clinician cannot be effective if he has too much emotion or is frightened by the patient. Keeping the clinician safe is the first step toward patient safety. Approximately 90% of all emotional information and more than 50% of the total information in spoken English is communicated not by what one says but by body language, especially tone of voice.25 When the clinician approaches the agitated patient, he must monitor his own emotional and physiologic response so as to remain calm and, therefore, be capable of performing verbal de-escalation.26

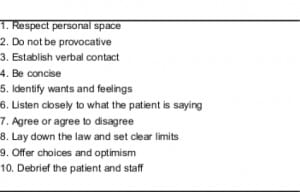

Guideline: 10 Domains of De-Escalation Exist That Help Clinicians’ Care of Agitated Patients

Review of the literature establishes 10 domains of de-escalation (Table 2).27

Domain I: Respect Personal Space

Key Recommendation: Respect the Patient’s and Your Personal Space. When approaching the agitated patient, maintain at least 2 arm’s lengths of distance between you and the patient. This not only gives the patient the space he needs, but also gives the clinician the space needed to move out of the way if the patient were to kick or otherwise strike out. The clinician may want to give himself more distance in order to feel safe; and, if a patient tells you to get out of the way, do so immediately. Both the patient and the clinician should be able to exit the room without feeling that the other is blocking his way.

A high percentage of patients have a past history of trauma, and the emergency experience has the potential for repeating the traumatic experience when specific aspects of personal space are ignored. A person who lives on the street may be very sensitive about protecting his belongings. Those who have been sexually abused may be apprehensive about being unclothed, which can increase their sense of vulnerability and cause humiliation.

Domain II: Do Not Be Provocative

Key Recommendation: Avoid Iatrogenic Escalatio.The clinician must demonstrate by body language that he will not harm the patient, that he wants to listen, and that he wants everyone to be safe. Hands should be visible and not clenched. Avoid concealed hands, which imply a concealed weapon.20 Knees should be slightly bent. The clinician should avoid directly facing the agitated patient and should stand at an angle to the patient so as not to appear confrontational. A calm demeanor and facial expression are important. Excessive, direct eye contact, especially staring, can be interpreted as an aggressive act. Closed body language, such as arm folding or turning away, can communicate lack of interest. It is most important that the clinician’s body language be congruent with what he is saying. If not, the patient will sense that the clinician is insincere or even “faking it” and may become more agitated and angry. It is also important to monitor closely that other patients or individuals do not provoke the patient further.

According to Lazare and Levy,28 humiliation is an aggressive act where a person has threatened another person’s integrity and very self. In some cases, humiliation itself can be traumatic. Therefore, do not challenge the patient, insult him, or do anything else that can be perceived as humiliating.

Domain III: Establish Verbal Contact

Key Recommendation: Only 1 Person Verbally Interacts with the Patient. The first person to make contact with the patient should be the person designated to de-escalate the patient. If that person is not trained or is otherwise unable to take on this role, another person should be designated immediately.

Multiple people verbally interacting can confuse the patient and result in further escalation. While the designated person is working with the patient, another team member should alert staff to the encounter, while removing innocent bystanders.

Key Recommendation: Introduce Yourself to the Patient and Provide Orientation and Reassurance. A good strategy is to be polite. Tell the patient your title and name. Rapidly diminish the patient’s concerns about your role by explaining that you are there to keep him safe and make sure no harm comes to him or anyone else in the emergency setting. If the patient is very agitated, he may need additional reassurance that the clinician wants to help him regain control. Orient the patient as to where he is and what to expect. If the patient’s name is unknown, ask for his name. Judgment is required in deciding whether to call the person by his first or last name. Although some prefer calling all patients by their last names, this formality, in some situations, can add to a patient’s suspicion and appear patronizing. When in doubt, it is best to ask the patient how he prefers to be addressed; this act communicates that he is important and, from the very beginning of the interaction, that he has some control over the situation.

Domain IV: Be Concise

Key Recommendation: Be Concise and Keep It Simple. Since agitated patients may be impaired in their ability to process verbal information, use short sentences and a simple vocabulary. More complex verbalizations can increase confusion and can lead to escalation. Give the patient time to process what has been said to him and to respond before providing additional information.

Key Recommendation: Repetition Is Essential to Successful De-escalation. This involves persistently repeating your message to the patient until it is heard. Since the agitated patient is often limited in his ability to process information, repetition is essential whenever you make requests of the patient, set limits, offer choices, or propose alternatives. This repetition is combined with other assertiveness skills that involve listening to the patient and agreeing with his position whenever possible.19

Domain V: Identify Wants and Feelings

Examples of wants include succorance, the wish to ventilate to an empathic listener, a request for medication, some administrative intervention, such as a letter to an employer, or intervening with a difficult spouse or parent. Whether or not the request can be granted, all patients need to be asked what their request is.1 A statement like, “I really need to know what you expected when you came here,” is essential, as is the caveat “Even if I can’t provide it, I would like to know so we can work on it.”

Key Recommendation: Use Free Information to Identify Wants and Feelings. “Free information” comes from trivial things the patient says, his body language, or even past encounters one has had with the patient.19 Free information can help the examiner identify the patient’s wants and needs. This rapid connection based on free information allows the clinician to respond empathically and express a desire to help the patient get what he wants, facilitating rapid de-escalation of agitation.

A sad person wants something he has given up hope of having. A patient who is fearful wants to avoid being hurt. In a later discussion of aggression, it will be apparent that the aggressive patient has specific wants also, and identifying these wants is important for the management of the patient.

Domain VI: Listen Closely to What the Patient Is Saying

Key Recommendation: Use Active Listening. The clinician must convey through verbal acknowledgment, conversation, and body language that he is really paying attention to the patient and what he is saying and feeling. As the listener, you should be able to repeat back to the patient what he has said to his satisfaction. Such clarifying statements as “Tell me if I have this right…” is a useful technique. Again, this does not mean necessarily that you agree with the patient but, rather, that you understand what he is saying.

Key Recommendation: Use Miller’s Law. Miller’s law states, “To understand what another person is saying, you must assume that it is true and try to imagine what it could be true of.”25 If you follow this law, you will be trying to understand. If you are truly trying to imagine how it could be true, you will be less judgmental, and the patient will sense that you are interested in what he is saying and this will significantly improve your relationship with the patient. For example, if the patient’s agitation is driven by the delusion that someone is following him and intends to cause him harm, you can imagine how this is true from the patient’s standpoint and engage the patient in conversation as to why this is happening to him and who would want to harm him. This will convey your interest and will result in the patient engaging in conversation about that which is driving his agitation. By engaging in conversation, the patient will begin to see that you care, which in turn, fosters de-escalation.

Domain VII: Agree or Agree to Disagree

Fogging is an empathic behavior in which one finds something about the patient’s position with which he can agree.19 It can be very effective in developing one’s relationship with the patient. There are 3 ways to agree with a patient. The first is agreeing with the truth. If the patient is agitated after 3 attempts to draw his blood, one might say, “Yes, she has stuck you 3 times. Do you mind if I try?” The second is agreeing in principle. For the agitated patient who is complaining that he has been disrespected by the police, you don’t have to agree that he is correct but you can agree with him in principle by saying, “I believe everyone should be treated respectfully.” The third is to agree with the odds. If the patient is agitated because of the wait to see the doctor and states that anyone would be upset, an appropriate response would be, “There probably are other patients who would be upset also.” Using these techniques, it is usually easy to find a way of agreeing, and one should agree with the patient as much as possible. Clinicians may find themselves in a position where they are being asked to agree with an obvious delusion or something else the clinician can obviously have no knowledge of. In this situation, acknowledge that you have never experienced what the patient is experiencing but that you believe that he is having that experience. However, if there is no way to honestly agree with the patient, agree to disagree.

Domain VIII: Lay Down the Law and Set Clear Limits

Key Recommendation: Establish Basic Working Conditions. It is critical that the patient be clearly informed about acceptable behaviors. Tell the patient that injury to him or others is unacceptable. If necessary, tell the patient that he may be arrested and prosecuted if he assaults anyone. This should be communicated in a matter-of-fact way and not as a threat.

Key Recommendation: Limit Setting Must Be Reasonable and Done in a Respectful Manner. Set limits demonstrating your intent and desire to be of help but not to be abused by the patient. If the patient is causing the clinician to feel uncomfortable, this must be acknowledged. Often telling the patient that his behavior is frightening or provocative is helpful if it is matched with an empathic statement that the desire to help can be interrupted or even derailed if the clinician feels angry, fearful, etc.

The bottom line is that good “working conditions” require that both patient and clinician treat each other with respect. Being treated with respect and dignity must go both ways. Violation of a limit must result in a consequence, which (1) is clearly related to the specific behavior; (2) is reasonable; and (3) is presented in a respectful manner.

Some behaviors, eg, punching a wall or even breaking a chair, may not automatically indicate the need for seclusion or restraint, and the patient can continue to be de-escalated with some increase in limit setting and consequences. Reassure the patient that you want to help him regain control and establish acceptable behavior.

Key Recommendation: Coach the Patient in How to Stay in Control. Once you have established a relationship with the patient and determined that he has the capability to stay in control, teach him how to stay in control. Use gentle confrontation with instruction: “I really want you to sit down; when you pace, I feel frightened, and I can’t pay full attention to what you are saying. I bet you could help me understand if you were to calmly tell me your concerns.”

Domain IX: Offer Choices and Optimism

Key Recommendation: Offer Choices. For the patient who has nothing left but to fight or take flight, offering a choice can be a powerful tool. Choice is the only source of empowerment for a patient who believes physical violence is a necessary response. In order to stop a spiraling aggression from turning into an assault, be assertive and quickly propose alternatives to violence. While offering choices, also offer things that will be perceived as acts of kindness, such as blankets, magazines, and access to a phone. Food and something to drink may be a choice the patient is willing to accept that will stall aggressive behaviors. Be mindful that these choices must be realistic. Never deceive a patient by promising something that cannot be provided for him. For example, a patient should not be promised a chance to smoke when the hospital has a no-smoking policy.

Key Recommendation: Broach the Subject of Medications. The goal of medicating the agitated patient is not to sedate but to calm him. As Allen and colleagues11 point out, a calm, conscious patient is one who can participate in his own care and work with the crisis clinician toward an appropriate treatment disposition, which is of benefit to the patient and also to the staff. It can decrease length of stay and make the emergency department experience a positive one.

When medications are indicated, offer choices to the patient. Timing is essential. Do not rush to give medication but, at the same time, do not delay medication when needed. Using increasing strategies of persuasion is a sound technique (Table 3). For example, the first step is not to mention medication at all but to ask the patient what he needs, what works. Try to get the request for medication to come from the patient himself, or perhaps the patient has a better idea.

If the patient does not mention medication and the clinician believes it is indicated, then state clearly to the patient that you think he would benefit from medication. Ask the patient what medication has helped him in the past or state, “I see that you’re quite uncomfortable. May I offer you some medication?”

Gentle confrontation may also be useful: “It’s important for you to be calm in order for us to be able to talk. How can that be accomplished? Would you be willing to take some medication?”

Another step is one just short of involuntary medication. “Mr Smith, you’re experiencing a psychiatric emergency. I’m going to order you some emergency medicine.” This strategy is authoritative, as in being knowledgeable and self-assured, possessing expertise, having the ability to explain one’s thinking, and being persuasive. Giving the patient a choice in either oral or parenteral administration can help give the patient some control. He may willingly take medication if the means of administration is a choice, even if the administration of medication itself is not a choice. Appealing to the patient’s desire to stay in control and the clinician’s mandate to keep everyone safe, one might say to the patient: “I can’t let any harm come to you or anyone else” or “I need to protect you from hurting someone, so I would like for you to take some medication to help you stay in control.” The clinician then says to the patient as many times as necessary, “Would you like to take medication by mouth or by a shot?” Emphasizing the protection aspect is very important and can be effective in empowering the patient to stay in control. “I feel medications can help, would you like a pill you can swallow, a pill that will melt in your mouth, or a liquid? If you agree to take a pill by mouth you can avoid taking a shot.” Even when there is no choice but to give an injection, the clinician can give a choice as to which drug is to be used, emphasizing that one has a more beneficial side-effect profile.

Finally, when verbal attempts to de-escalate fail, more coercive measures such as restraints or injectable medication may be necessary to ensure safety but always as a last resort.

Key Recommendation: Be Optimistic and Provide Hope. Be optimistic but in a genuine way. Let patients know that things are going to improve and that they will be safe and regain control. Give realistic time frames for solving a problem and agree to help the patient work on the problem. When the patient states, “I want to get out of here,” the clinician can respond, “I want that for you as well; I don’t want you to have to stay here any longer than necessary; how can we work together to help you get out of here?”

Domain X: Debrief the Patient and Staff

Key Recommendation: Debrief the Patient. After any involuntary intervention with an agitated patient, it is the responsibility of the clinician who ordered these interventions to restore the therapeutic relationship to alleviate the traumatic nature of the coercive intervention and to decrease the risk of additional violence.

Start by explaining why the intervention was necessary. Let the patient explain events from his perspective. Explore alternatives for managing aggression if the patient were to get agitated again. Teach the patient how to request a time out and how to appropriately express his anger. Explain how medications can help prevent acts of violence and get the patient’s feedback on whether his concerns have been addressed. Finally, debrief the patient’s family who witnessed the incident.

Once the patient is calm, the clinician can acknowledge and work with the patient on a deeper level, help put the patient’s concerns into perspective, and assist him in problem solving his initial precipitating situation. Since prevention of agitation is the best way to treat it, planning with the patient is best: “What works when you are very upset as you were today? What can we/you do in the future to help you stay in control?”

Key Recommendation: Debrief the Staff. If restraint or force needs to be used, it is important that the staff be debriefed on the actions after the event. Staff should feel free to suggest both what went well during the episode, and what did not, and recommend improvements for the next episode.

THE AGGRESSIVE PATIENT

As previously noted the extent of aggression associated with agitation has not been clearly established.5 However, some agitated patients are aggressive and the approach to the patient depends upon the type of aggression. Moyer29 has defined several types of aggression, some of which are commonly seen in the emergency setting. Types of aggression also have been identified in the setting of a correctional facility30 and by martial arts instructors.31 These identified types can be placed in Moyer’s classification and are important because principles of management have been developed for each of the different types of aggression. Some of the management techniques used in correctional facilities and taught in the martial arts are not recommended for use in the healthcare setting. However, the principles allow us to develop techniques appropriate to the healthcare setting and are discussed here. It will be apparent that there is always something the patient wants. As discussed earlier, identifying the patient’s wants is important and, in this case, determines how the patient is managed.

Instrumental aggression is used by those who have found they can get what they want by violence or threats of violence. This aggression is not driven by emotion and can be handled by using unspecified counter offers to the aggressor’s threat. If a patient threatens to hurt someone if he doesn’t get a cigarette, a counter offer might be, “I don’t think that’s a good idea.” The patient’s next response may be, “What do you mean?” A counter offer would be, “Let’s not find out.”

Fear driven aggression is not self defense. The patient wants to avoid being hurt and may attack to prevent someone from hurting him. Give the fearful patient plenty of space. Do not have a show of force or in any other way intimidate the patient or make him feel threatened, as this will feed into the patient’s belief that he is going to be hurt. De-escalation involves matching the patent’s pace until he begins to focus on what is being said rather than his fear. If the patient says, “Don’t hurt me. Don’t hurt me.” Counter with the same pace by saying, “You’re safe here. You’re safe here.”Try to decrease the pace tohelp the patient calm down.

Irritable aggression comes in 2 forms. The first is the patient who has had boundaries violated. Someone has cheated him, humiliated him, or otherwise emotionally wounded him. He is angry and trying to put his world back together, ie, he is trying to regain his self-worth and integrity. This patient wants to be heard and have his feelings validated. This type of aggression is identified by the patient’s telling you what has made him angry. De-escalation involves setting conditions for the patient to be heard. Fogging and the broken record approach19 are most helpful. A typical scenario is the patient who found out that his girlfriend had cheated on him. His friends kidded him and a fight ensued. He was brought in by police. On arrival the patient is furious. He states that his girlfriend had cheated on him and that the police are treating him unfairly. The initial response is to agree in principle that the patient’s anger is justified. This is followed by telling the patient that you want to know more but cannot until he regains control so that “we can talk.” The patient may respond that nobody understands. The response is that he may be right but you would like to try to understand. This loop may need repeated a dozen or more times before the patient complies.

The second form of irritable aggression occurs in persons who are chronically angry at the world and are looking for an excuse to “go off.” They give no reason for their anger. They want to release the constant pressure resulting from their world view. They make unrealistic and erratic demands and use these as an excuse to attack when their demands are not met. They get enjoyment out of creating fear and confusion and may make feigned attacks to intimidate those who are working with them. Do not react in a startled or defensive way. These patients are looking for an emotional response from anyone who is an audience. Don’t give them one and remove all other patients, unnecessary staff members, and bystanders from the area. Use emotionless responses. De-escalation involves giving the patient choices other than violence to get what he wants. As he makes erratic demands, use the broken record to return to the options you can offer. Let him know you will work with him but only when he is willing to be cooperative. Set firm limits to protect staff and other patients and intervene with restraint if the limit is violated. Unfortunately, many of these patients will test the limit by doing just what you have asked them not to do and end up in restraints.

CONCLUSION

Verbal de-escalation techniques have the potential to decrease agitation and reduce the potential for associated violence, in the emergency setting. But while much has been written on the psychopharmacologic approaches to agitated patients, until now there has been relatively little discussion about verbal methods.

Modern clinical thinking endorses less coercive interventions, in which the patient becomes a collaborative partner with staff members in managing behavior. These approaches may result in many benefits over traditional procedures. Patients spiraling into agitation can be calmed without forced medication or restraint; most importantly, such benign treatment can empower the patient to stay in control while building trust with caregivers. This may help patients to confidently seek help earlier in the future, and avoid subsequent episodes of agitation altogether.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Leslie Zun, MD

Submission history: Submitted July 29, 2011; Revision received September 6, 2011; Accepted September 26, 2011

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

DOI: 10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6864

Address for Correspondence: Janet S. Richmond, MSW

575 Chestnut St, Waban, MA 02468

E-mail: JanetRichmond@att.net

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding, sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Lazare A, Eisenthal S, Wasserman L. The customer approach to patienthood: attending to patient requests in a walk-in clinic. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32:553–558. [PubMed]

2. Shame Lazare A. and humiliation in the medical encounter. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1653–1658. [PubMed]

3. Day RK. Psychomotor agitation: poorly defined and badly measured. J Affect Disord. 1999;55:89–98. [PubMed]

4. Lindenmayer JP. The pathophysiology of agitation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61((suppl 14)):5–10.[PubMed]

5. Nordstrom K, Allen MH. Managing the acutely agitated and psychotic patient. CNS Spectr.2007;12((suppl 17)):5–11. [PubMed]

6. Zeller SL, Rhoades RW. Systematic reviews of assessment measures and pharmacologic treatments for agitation. Clin Ther. 2010;32:403–425. [PubMed]

7. Holloman GH, Jr, Zeller SL. Overview of Project BETA: best practices in evaluation and treatment of agitation. West J Emerg Med. 2011;13:1–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

8. Beck JC, White KA, Gage B. Emergency psychiatric assessment of violence. Am J Psychiatry.1991;148:1562–1565. [PubMed]

9. Compton MT, Craw J, Rudisch BE. Determinants of inpatient psychiatric length of stay in an urban county hospital. Psychiatr Q. 2006;77:173–188. [PubMed]

10. Knutzen M, Mjosund NH, Eidhammer G, et al. Characteristics of psychiatric inpatients who experienced restraint and those who did not: a case-control study. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:492–497. [PubMed]

11. Allen MH, Currier GW, Carpenter D, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: treatment of behavioral emergencies. 2005;2005;2005;1111((suppl 1))((suppl 1)):110–112. 5–108. quiz in J Psychiatr Pract. J Psychiatr Pract.

12. Isbister GK, Calver LA, Page CB, et al. Randomized controlled trial of intramuscular droperidol versus midazolam for violence and acute behavioral disturbance: the DORM study. Ann Emerg Med.2010;56:392–401. [PubMed]

13. Livingston JD, Verdun-Jones S, Brink J, et al. A narrative review of the effectiveness of aggression management training programs for psychiatric hospital staff. J Forensic Nurs. 2010;6:15–28.[PubMed]

14. Morrison EF. An evaluation of four programs for the management of aggression in psychiatric settings. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2003;17:146–155. [PubMed]

15. Farrell G, Cubit K. Nurses under threat: a comparison of content of 28 aggression management programs. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2005;14:44–53. [PubMed]

16. Dupont RT. The crisis intervention team model: an intersection point for the criminal justice system and the psychiatric emergency service. In: Glick RL, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, et al., editors.Emergency Psychiatry: Principles and Practice. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

17. The University of Memphis. CIT. CIT Center Web site. Available at: http://cit.memphis.edu. Accessed August 29, 2011.

18. Allen M, Forster P, Zealberg J, et al. Report and recommendations regarding psychiatric emergency and crisis services: A review and model program descriptions. American Psychiatric Association Task Force on Psychiatric Emergency Services Web site. Available at:http://www.emergencypsychiatry.org/data/tfr200201.pdf. Accessed June 13, 2011.

19. Smith MJ. When I Say No, I Feel Guilty: How To Cope – Using the Skills of Systematic Assertive Therapy. New York, NY: Dial Press/Bantum Books;; 1975.

20. Fishkind A, Agitation II: Glick RL, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, et al, eds. Emergency Psychiatry: Principles and Practice. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. De-escalation of the aggressive patient and avoiding coercion.

21. Swift RH, Harrigan EP, Cappelleri JC, et al. Validation of the behavioural activity rating scale (BARS): a novel measure of activity in agitated patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2002;36:87–95. [PubMed]

22. Yudofsky SC, Silver JM, Jackson W, et al. The Overt Aggression Scale for the objective rating of verbal and physical aggression. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:35–39. [PubMed]

23. Brizer DA, Convit A, Krakowski M, et al. A rating scale for reporting violence on psychiatric wards. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1987;38:769–770. [PubMed]

24. Palmstierna T, Wistedt B. Staff observation aggression scale, SOAS: presentation and evaluation.Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1987;76:657–663. [PubMed]

25. Elgin SH. Language in Emergency Medicine: A Verbal Self-Defense Handbook. Bloomington, IN: XLibris Corporation;; 1999.

26. Kleespies PM, Richmond JS. Evaluating behavioral emergencies: the clinical interview. In: Kleespies PM, editor. Behavioral Emergencies: An Evidence-Based Resource for Evaluating and Managing Risk of Suicide, Violence, and Victimization. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association;; 2008. pp. 33–35.

27. Fishkind A. Calming agitation with words, not drugs: 10 commandments for safety. Current Psych. 2002;2011;1(4) Available at:http://www.currentpsychiatry.com/pdf/0104/0104_Fishkind.pdf. Accessed June 13,

28. Lazare A, Levy RS. Apologizing for humiliations in medical practice. Chest. 2011;139:746–751.[PubMed]

29. Moyer KE. Kinds of aggression and their physiological basis. Commun Behav Biol. 1968;2:65–87.

30. Barnhart TE. Four types of correctional violence. Corrections Web site. Available at:http://www.corrections.com/news/article/23111-four-4-types-of-correctional-violence. Accessed September 2, 2011.

31. MacYoung M. Four types of violence. No Nonsense Self-Defense Web site. Available at:http://nononsenseselfdefense.com/four_types_of_ violence.htm. Accessed September 2, 2011.