| Author | Affiliation |

| Kenneth S. Whitlow, DO | Kaweah Delta Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Visalia, California |

| Babette W. Davis, DO, MPH | Baystate Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Springfield, Massachusetts |

Introduction

Case Report

Discussion

ABSTRACT

High altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) is a form of high altitude illness characterized by cough, dyspnea upon exertion progressing to dyspnea at rest and eventual death, seen in patients who ascend over 2,500 meters, particularly if that ascent is rapid. This case describes a patient with no prior history of HAPE and extensive experience hiking above 2,500 meters who developed progressive dyspnea and cough while ascending to 3,200 meters. His risk factors included rapid ascent, high altitude, male sex, and a possible genetic predisposition for HAPE.

INTRODUCTION

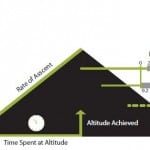

High altitude illness (HAI) is a spectrum of conditions characterized by the nausea, vomiting, and sleep disturbances typical of acute mountain sickness (AMS), the ataxia and eventual coma seen in high altitude cerebral edema (HACE), and the cough, dyspnea, and eventual death typical of high altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE).1 Though uncommon, HAPE is a potentially life-threatening non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema that occurs within 2-4 days after rapid ascent above 2,500 meters (8,000 feet) (Figure).2 Clinically, the patient will be afebrile and have one or more of the following: tachypnea, hypoxemia with an oxygen saturation 10 points lower than expected after correcting for altitude, and inspiratory crackles in the right middle lobe which become diffuse as the process progresses. Known risk factors include male sex, cold environmental temperatures, vigorous exertion, and preexisting conditions.3 Evidence suggests that genetics may also play a role.3 HAPE is best treated with simulated or actual descent, nifedipine, or hydralazine. If left untreated, death will ensue.

Figure. Incidence and risk factors for high altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE).

CASE REPORT

A 25-year-old previously healthy Caucasian male was evacuated from 3,200 meters after experiencing nausea, headache, shortness of breath, and cough. The patient, who frequently enjoyed short mountaineering trips from his home at sea level, had been at altitude the previous weekend with no concerns. On the first day of ascent his group had slept at 1,800 meters and ascended to 3,200 meters on day two. Subsequently the patient felt malaised and experienced a cough. Later on day two he developed nausea and insomnia. By the morning of day three his cough worsened and progressed to frank shortness of breath, but he refused to descend. As the day progressed so did his symptoms, he was no longer able to self-descend and was airlifted to base and transported to a community academic emergency department (ED) approximately one hour away.

During transport he reported complete resolution of his headache and nausea immediately after landing at base altitude but continued to complain of progressively worsening dyspnea despite high-flow oxygen via non-rebreather mask. His vital signs on arrival in the ED were: temperature: 98.6°F, heart rate: 86, blood pressure 131/76, respiratory rate: 20, and oxygen saturation 80% on room air, which represented an improvement from prehospital saturations between 60-70%. On exam he had diffusely coarse breath sounds, audible without a stethoscope, with use of accessory muscles, but was otherwise well appearing. He was given 100% oxygen, albuterol and ipratropium nebulizers, inhaled and intravenous dexamethasone, 5mg of intravenous hydralazine, and 40mEq of intravenous furosemide. Subsequently his oxygen saturations improved to the mid 90s on two liters of oxygen via nasal cannula, and his breath sounds and respiratory effort improved substantially. He was placed in observation, was continued on intravenous dexamethasone, and was successfully discharged the next day. After discharge the patient’s father remembered that he had been forced to abort a hiking trip at altitude as a young man due to sudden onset of “asthma,” a condition of which he had no prior diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

This patient presented with a near-classical presentation of HAPE. As with 50% of HAPE patients, he also exhibited symptoms of AMS manifesting as nausea and poor sleep,3 which was a probable manifestation of periodic breathing of altitude, a phenomenon where the hypoxia and alkalosis of altitude result in Cheyne-Stokes respiration that can disrupt sleep.3,4 His risk factors for HAPE included rapidly attaining high altitude from his baseline of sea level, male sex, and possible genetic predisposition.3

HAPE is believed to be precipitated by the hypobaric hypoxemia of ascent resulting in a poor ventilatory response and increased sympathetic tone with mean pulmonary artery pressures above 35mmHg. The resultant pulmonary hypertension is coupled with inadequate production of endothelial nitric oxide and an overproduction of endothelin, resulting in disruption of the alveolar-capillary barrier.5 High molecular weight proteins, cells, and fluid enter the alveolar space with eventual alveolar hemorrhage. In the patient this is manifested as a non-productive cough, mild dyspnea on exertion, and difficulty ascending.3 This progresses to dyspnea at rest; pink, frothy sputum that may include frank blood; and drowsiness. Lab studies may show an increased white blood cell count with a normal brain natriuretic peptide, likely ruling out cardiogenic pulmonary edema. The history will most likely differentiate HAPE from pneumonia.

Although this patient had no prior symptoms of HAPE despite his frequent mountaineering, his father described having what he believed was acute asthma while climbing, and genetics appear to be a risk factor for HAPE.6,7 It is believed that the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, nitric oxide pathway, and hypoxia-inducible factor pathway, are controlled by genes that differ in HAPE-susceptible patients.6 Other studies provide evidence of mitochondrial DNA8 or heat shock protein9 polymorphisms in HAPE-susceptible individuals or differences within the major histocompatibility complex.10 Although the genetic connection is not yet clearly established by the research, these and future studies may help to better explain our patient’s risk, protecting his offspring in future generations.

A patient developing any form of HAI is best treated with descent.2 The goal with HAPE patients, however, is to reduce the pulmonary artery pressure. This is best achieved with supplemental oxygen, which may be available before initiating descent. Rest and limiting cold exposure will also be beneficial.3 Descent, either with minimal effort by the patient (e.g., via air or ground evacuation versus self-descent) or simulated descent through the use of a hyperbaric chamber, will further reduce pulmonary pressures. Pharmacologic treatment focuses on reducing pulmonary artery resistance. Nifedipine or hydralazine have shown to be of benefit, particularly if oxygen therapy is unavailable. As arterial vasodilators, they will reduce pulmonary vascular resistance, pulmonary artery pressure, systemic vascular resistance and blood pressure while improving arterial oxygenation pressure. Although there is currently evidence for the use of phosphodiesterase inhibitors, dexamethasone, salmeterol, and acetazolamide in HAPE prophylaxis, there is no current evidence supporting their use as treatment once HAPE has developed.

Advice given to any patient with previous HAPE includes gradual ascent with acclimation to elevation. Nifedipine, tadalafil, sildenafil, dexamethasone, acetazolamide, or salmeterol may be used prophylactically. Nifedipine should be carried for potential self-administered treatment.2 A portable pulse oximeter is a small and relatively inexpensive monitoring device that a previous HAPE patient can easily carry and use for early detection of disease provided they have been instructed in its interpretation at altitude. More complex solutions include portable oxygen and hyperbaric tents. Knowledge of the nearest available oxygen, hyperbaric tent, and evacuation resources may be a more realistic safety plan and exit strategy.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Joel Schofer, MD, MBA

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Kenneth S. Whitlow, Baystate Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, 759 Chestnut Street, Springfield, MA 0199. Email: witdavis@gmail.com

Submission history: Submitted June 3, 2014; Accepted July 12, 2014

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

- Gallagher SA, Hackett P, Rosen JM. High altitude illness: Physiology, risk factors, and general prevention. In: Basow, DS, Ed. UpToDate. Waltham MA: 2013.

- Stream JO, Grissom CK. Update on high-altitude pulmonary edema: pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Wilderness Environ Med. 2008;19:293.

- Gallagher SA, Hackett P. High altitude pulmonary edema. In: Basow, DS, Ed. UpToDate. Waltham MA: 2013.

- Wickramasinghe H, Anholm JD. Sleep and breathing at high altitude. Sleep Breath. 1998;3:89-102.

- Bartsch P, Mairbauri H, Maggiorini M, et al. Physiological aspects of high-altitude pulmonary edema. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1101

- Luo Y, Zou Y, Gao Y. Gene polymorphisms and high-altitude pulmonary edema susceptibility: a 2011 update. Respiration. 2012;84:155-62.

- Lorenzo VF, Yang Y, Smonson TS, et al. Genetic adaptation to extreme hypoxia: study of high-altitude pulmonary edema in a three-generation Han Chinese family. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2010; 44:198.

- Luo Y, Gao W, Chen Y, et al. Rare mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms are associated with high altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) susceptibility in Han Chinese. Wilderness Environ Med. 2012;23:128132.

- Qi Y, Niu WQ, Zhu TC, et al. Genetic interaction of HSP70 family genes polymorphisms with high-altitude pulmonary edema among Chinese railway constructors at altitudes exceeding 4000 meters. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;405:17-22.

- Hanaoka M, Kubo K, Yamazaki Y, et al. Association of high-altitude pulmonary edema with the major histocompatibility complex. Circulation. 1998;97:1124-8.