| Author | Affiliation |

| Mian Adnan Waheed, MD | Texas Tech University Health Science Center, Department of Internal Medicine, Odessa, Texa |

| Lavi Oud, MD | Texas Tech University Health Science Center, Department of Internal Medicine, Odessa, Texa |

Introduction

Case Report

Discussion

ABSTRACT

Propofol is frequently used in the emergency department to provide procedural sedation for patients undergoing various procedures and is considered to be safe when administered by trained personnel. Pulmonary edema after administration of propofol has rarely been reported. We report a case of a 23-year-old healthy male who developed acute cough, hemoptysis and hypoxia following administration of propofol for splinting of a foot fracture. Chest radiography showed bilateral patchy infiltrates. The patient was treated successfully with supportive care. This report emphasizes the importance of this potentially fatal propofol-associated complication and discusses possible underlying mechanisms and related literature.

INTRODUCTION

Propofol (2,6-diisopropylphenol) is an ultrashort-acting intravenous hypnotic and sedative agent formulated as an emulsion containing soybean oil, egg phospholipid and glycerol.1 It is commonly used for induction of anesthesia in the operating room, as routine sedation in the intensive care setting, and also for procedural sedation in the emergency department (ED). Common adverse effects of propofol include hypotension, respiratory depression, bradycardia and pain during injection. Pulmonary edema after administration of propofol has rarely been reported.2-5 To our knowledge, we report the first case of propofol-related pulmonary edema in the United States.

CASE REPORT

A 23-year-old man presented to the ED with pain and swelling of his left foot secondary to a work-related accident. He had no preexisting medical problems. The patient was a smoker and denied drug allergies, use of medications or illicit drugs. He was noted to be in severe distress due to pain. His temperature was 36.7oC, heart rate 88 beats/min, blood pressure 133/90 mm Hg, respirations 20 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry (SpO2) 100% on room air. His weight was 66 kg and his physical examination was unremarkable, except for left foot swelling and tenderness. He had a Mallampatti score of 1 and an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification of 1. Routine initial laboratory workup, including complete blood count, electrolytes, renal and liver function panel, urinalysis and urine drug screening, was within normal range. A nondisplaced proximal third metatarsal fracture was noted on plain radiography of the left foot. The patient had a low pain tolerance and thus requested sedation and analgesia for any manipulation of his foot. In order to splint his foot, procedural sedation, along with analgesia were provided, including intravenous meperidine 75mg and intravenous propofol in 75mg aliquots up to a total of 350mg over a period of one hour. The patient was under continuous cardiopulmonary monitoring with three-lead electrocardiography and SpO2 monitoring, as well as close observation by nursing staff to check for signs of respiratory dysfunction or other adverse effects. He tolerated the procedure well, adequately maintaining his airway. His SpO2 was >95% throughout the procedure, on oxygen at 15 liters per minute through a non-rebreather mask. After the procedure, oxygen supplementation was gradually reduced over 15 minutes.

At 60 minutes following the procedure, the patient was completely awake and oriented, saturating 96% on room air. Ten minutes later, the patient developed acute cough with moderate quantity hemoptysis. Arterial blood gas analysis showed pH of 7.35, PaO2 44mmHg, PaCO2 42mmHg and SaO2 76%. His temperature was 36.6oC, heart rate 95 beats/min, blood pressure 128/70mmHg, respirations 18 breaths/min, and SpO2 80%. Supplemental oxygen through nasal cannula at four liters per minute was initiated with improvement in SaO2 to 90%. Physical examination revealed bilateral coarse crackles throughout both lung fields with normal heart sounds and normal neck examination. Chest radiography showed patchy bilateral lung airspace infiltrates (Figure), which were confirmed on computed tomography angiography that was otherwise unremarkable. Additional diagnostic studies obtained following development of hypoxemia, including coagulation profile, d-dimer, as well as serial electrocardiograms and troponin I assays, were within normal range. Serum creatinine kinase was 633IU/L.

Figure. Chest radiography showing diffuse bilateral patchy infiltrates 60 minutes after propofol administration.

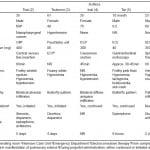

Table. Clinical characteristics of patients with propofol-associated pulmonary edema.

The patient was admitted to a telemetry unit. Intravenous ceftriaxone 2 grams daily and azithromycin 500mg daily were initiated empirically, along with intravenous furosemide 40mg every six hours. Workup for an infectious etiology, including tuberculosis by interferon-gamma release assay, coccidioidomycosis complement fixation, histoplasmosis antibody, blastomycosis antibody, aspergillus antibody, human immunodeficiency virus antibody, along with sputum and blood cultures, was negative. Echocardiography was unremarkable. A C-reactive protein test was normal and an antinuclear antibody test was negative. A follow-up complete blood count was normal. Over the course of next two days the patient’s hypoxia and hemoptysis resolved with no additional treatment. Follow-up chest radiography two days after admission showed near-complete resolution of lung infiltrates, and the patient was discharged from the hospital in stable, asymptomatic condition.

DISCUSSION

Propofol is frequently used for procedural sedation in the ED and is considered to be safe when administered by trained personnel.6 Typical initial dosage of propofol used for procedural sedation is 1mg/kg intravenously, followed by 0.5mg/kg every 3min titrated to the desired level of sedation. Doses used for induction of anesthesia are around 2-2.5mg/kg.7

While not the primary focus of the present report, the care of the reported patient could have been alternatively facilitated by using a regional nerve block, thus avoiding exposure to systemic procedural sedation, its attendant risks, and the associated need for additional monitoring. However, as noted by others,8 regional anesthesia requires special training and expertise, and may not be consistently available. Our findings underscore the variability in clinical practice among emergency medicine clinicians and the potential for improvement.

We describe development of hemoptysis and pulmonary edema following the administration of propofol for conscious sedation. While hemoptysis is an uncommon manifestation of pulmonary edema, it has been reported previously.9,10 Anesthesia-related pulmonary edema has been associated with airway obstruction, gas embolism, cardiac failure, fluid overload, acid aspiration, reactions to blood products and drug hypersensitivity reactions.11,12

Several alternative causes of hypoxic respiratory failure and lung infiltrates should be considered in our patient. Negative pressure pulmonary edema due to airway obstruction may complicate administration of central nervous system suppressants. However, the latter possibility is unlikely due to lack of signs of airway compromise throughout the closely monitored propofol administration and afterwards. In addition, the timing of hemoptysis does not support a diagnosis of negative pressure pulmonary edema. Cardiogenic pulmonary edema could not explain the findings in our patient as there was no evidence of myocardial damage or cardiac dysfunction. Similarly, fat embolism syndrome is unlikely to occur after a minor foot fracture. Although heroin overdose has frequently been reported to cause opiate-related pulmonary edema, meperidine has not been associated with pulmonary edema on literature review. No evidence of aspiration was noted on close observation, and pulmonary infection is unlikely, given the context of clinical onset, prompt resolution of clinical and radiographic abnormalities over two days, and a negative infection-related workup. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage can have similar initial presentation. However, diffuse infiltrates without change in hemoglobin and prompt clinical and radiographic resolution with supportive treatment makes this diagnosis implausible.

Acute pulmonary edema as an adverse effect of intravenous propofol has rarely been reported,2-5 as detailed in the table. Both male and female patients were described with ages ranging between 10 months to 61 years. Pulmonary edema pattern developed within 30 minutes to one hour and was associated with a varying severity of hypoxic and hypercarbic respiratory failure, requiring initiation and continuation of mechanical ventilation. Clinical and radiographic resolution occurred within five days.

The pathogenesis of pulmonary edema associated with propofol remains unclear, although anaphylactoid reaction is the most frequently postulated hypothesis.2,4,5,13 Propofol contains a diisopropyl chain and a phenol group, both of which have the potential to elicit an allergic reaction.14 An anaphylactoid reaction may increase vascular permeability and result in acute pulmonary edema. In addition, propofol has been shown to have significant vasodilator activity in the pulmonary vasculature in rats.15 These mechanisms may contribute to the development of pulmonary edema.

Given the uncertain pathogenesis, with no definite risk factors, no specific preventive steps can be taken beyond contemporary monitoring approach. Increased clinician awareness of this uncommon complication of propofol administration may help improve our understanding of the scope and underlying disease process. Pulmonary edema is a rare complication associated with propofol. Close monitoring and vigilance are required for early recognition and appropriate emergent treatment of associated complications. Further studies are needed to examine the epidemiology of propofol-associated pulmonary edema, its underlying mechanisms, and possible preventive measures.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Joel Schofer, MD, MBA

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Mian Adnan Waheed MD, Texas Tech University Health Science Center, Department of Internal Medicine, 701 West 5th Street, Odessa, Texas 79763. Email: Mian.waheed@ttuhsc.edu.

Submission history: June 24, 2014; Revision received July 19, 2014; Accepted July 22, 2014

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

- Marik PE. Propofol: therapeutic indications and side-effects. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:3639–49.

- Tsai MH, Kuo PH, Hong RL, et al. Anaphylaxis after propofol infusion for Port-A-Cath insertion in a 35-year old man. J Formos Med Assoc. 2001;100:424–6.

- Tsutsumi N, Tohdoh Y, Kawana S, et al. A case of pulmonary edema after electroconvulsive therapy under propofol anesthesia. Masui (Jpn J Anesthesiol). 2001;50:525-7.

- Inal MT, Memis D, Vatan I, et al. Late onset pulmonary edema due to propofol. Acta Anesthesiol Scand. 2008;52:1015–7.

- Tai Y, Chih-Ta Y, Yao-Jong Y. Acute pulmonary edema after intravenous propofol sedation for endoscopy in a child. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:320–2.

- Smally AJ, Nowicki TA, Simelton B. Procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17:317–22.

- Patanwala AE, Christich AC, Jasiak KD, et al. Age-related differences in propofol dosing for procedural sedation in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Med. 2013;44:823-8.

- Grabinsky A, Sharar S. Regional anesthesia for acute traumatic injuries in the emergency room. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9;1677-90.

- Ma JL, Dutch MJ. Extreme sports: extreme physiology. Exercise-induced pulmonary oedema. Emerg Med Australas. 2013;25:368-71.

- Takahashi T, Kinoshita K, Fuke T et al. Acute neurogenic pulmonary edema following electroconvulsive therapy: a case report. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34:703.

- Fisher MM, Stevenson IF. Unexplained acute membrane pulmonary oedema related to anesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1986;14:29–31.

- Stoelting RK. Acute pulmonary edema during anesthesia and operation in a healthy young patient. Anesthesiology. 1970;33:366–9.

- Laxenaire MC, Mata-Bermejo E, Moneret-Vautrin DA, et al. Life threatening anaphylactoid reactions to propofol. Anesthesiology. 1992;78:604–9.

- De Leon-Casasola OA, Weiss A, Lema MJ. Anaphylaxis due to propofol. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:384–6.

- Kaye A, Anwar M, Banister R et al. Responses to propofol in the pulmonary vascular bed of the rat. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1999;43:431-7.