| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Aaron Birch, MD | Department of Emergency Medicine, Madigan Army Medical Center, Tacoma, Washington |

| David Um, DO | Department of Emergency Medicine, Madigan Army Medical Center, Tacoma, Washington |

| Brooks Laselle, MD | Department of Emergency Medicine, Madigan Army Medical Center, Tacoma, Washington |

Introduction

Case report

Discussion

ABSTRACT

Superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome is most commonly the insidious result of decreased vascular flow through the SVC due to malignancy, spontaneous thrombus, infections, and iatrogenic etiologies. Clinical suspicion usually leads to computed tomography to confirm the diagnosis. However, when a patient in respiratory distress requires emergent airway management, travel outside the emergency department is not ideal. With the growing implementation of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), clinicians may make critical diagnoses rapidly and safely. We present a case of SVC syndrome due to extensive thrombosis of the deep venous system cephalad to the SVC diagnosed by POCUS.

INTRODUCTION

Superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome, first described by William Hunter in 1757 in a patient with syphilitic aneurysm,1 is defined as a constellation of symptoms that result from the decrease in vascular flow within the SVC. Traditionally, this has been understood to mean a drop in blood flow due to extrinsic compression of the SVC, usually from a thoracic tumor or other rigid structure within the thorax. Bronchogenic carcinoma, typically small or squamous cell, is responsible for nearly 80% of all cases of SVC syndrome, and lymphoma accounts for 15% of cases; yet spontaneous thrombus, infections, and iatrogenic etiologies are also described.2–4 The formation of venous thrombi secondary to pacemaker leads and central venous catheters is also a well-documented phenomenon.5,6

Several different anatomic factors contribute to the development of SVC syndrome. Principally, it is a relatively thin-walled vessel with low intravascular pressure, making it easy to compress. Subsequent compression impedes flow, which may contribute to thrombus formation, particularly if there is a thrombogenic foci already present, such as a central venous catheter. Additionally, there are a number of rigid and semi-rigid structures abutting the SVC, including vertebrae, ribs, and the aorta, which can cause compression.7,8

Imaging modalities, such as computed tomography (CT), are rapid, standardized, and give a detailed view of large areas. However, they nearly always require transport away from the resuscitation area and its resources. Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is a versatile imaging modality that is instantly available at the bedside, can be performed real-time in conjunction with resuscitation efforts, and can be performed serially without harmful ionizing radiation exposure to the patient or provider. Diagnosis of SVC syndrome with POCUS has not been previously described. This diagnosis is usually confirmed via traditional angiography, CT angiography, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).9–11

As such, the following is a case presentation of SVC syndrome due to extensive thrombosis of the deep venous system cephalad to the SVC diagnosed by POCUS.

CASE REPORT

A 71-year-old male with a past medical history of acute promyelocytic leukemia (PML) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma currently undergoing chemotherapy, presented to the emergency department (ED) via ambulance with a chief complaint of progressively worsening shortness of breath over the past three days. He experienced an acute worsening of this symptom accompanied by a gradual onset of upper body cyanosis beginning that morning.

Upon initial examination, the patient was in severe respiratory distress, speaking in three-word sentences. Initial vital signs were the following: blood pressure 124/94 mmHg, pulse 100 beats per minute, respiratory rate 28, temperature 97.9 F, SpO2 97% on 15 L/min non-rebreather mask. His head and upper torso had a generalized cyanotic appearance with a remarkably sharp demarcation line approximately at the nipples

Figure 1

Patient demonstrating sharp line of demarcation inferior to nipples separating pallor (inferior) and plethora (superior).

. Neck exam showed jugular venous distension without thyromegaly. The pulmonary exam revealed tachypnea, bilateral wheezing and the use of intercostal and supraclavicular accessory muscles. The abdomen was soft, mildly tender, distended, without masses, and with diminished bowel sounds. Extremity and neurologic exams were unremarkable.

Initial attempts at obtaining peripheral intravenous access proved exceedingly difficult despite obviously visible vasculature. After gaining peripheral access, several nurses noted difficulty in drawing blood and flushing medications and saline. POCUS was immediately performed to evaluate for the cause of his acute dyspnea and to locate vessels for vascular access, including a limited trans-thoracic echocardiogram, extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (EFAST), evaluation of the inferior vena cava for preload and bilateral internal jugular veins (IJV) assessments, for projected central venous access.

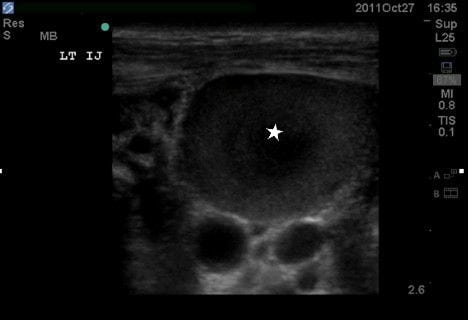

The echocardiogram showed a small pericardial effusion without evidence of tamponade with a grossly normal ejection fraction. The EFAST revealed absence of pneumothorax and a moderately large amount of free fluid in the abdomen consistent with previously known ascites. The vascular ultrasound (US) examinations (Figures 2–5) showed an inferior vena cava that collapsed more than 50% with each respiration, suggesting a central venous pressure of less than 8 mm Hg12; assessment of the IJVs demonstrated bilateral thromboses with extension into the subclavian and axillary veins bilaterally. There was no thrombosis in the right femoral vein and because of lack of functional IV access, a triple lumen central line was then placed under US guidance to allow resuscitation and treatment. Normal saline was administered with improvement in the patients’ symptoms.

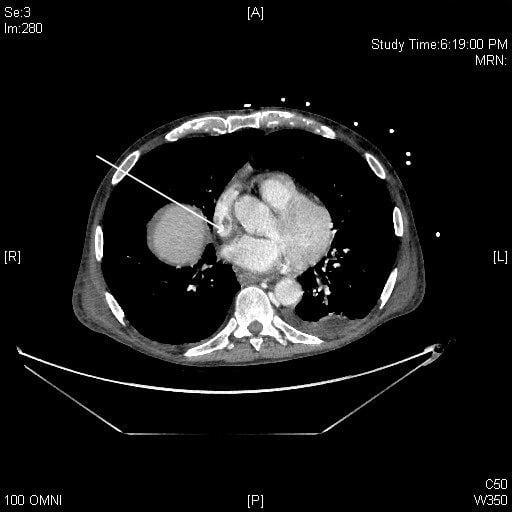

The electrocardiogram was without ischemia, and a chest radiograph was without acute pathology. Once the patient was stabilized, a CT of the head, neck and chest showed thrombus within the left innominate, right and left subclavians, and superior vena cava with total occlusion of the distal superior vena cava at the level of the cavo-atrial junction. These correlated with the POCUS findings and confirmed the cause of SVC syndrome. After discussion with the patient’s primary oncologist and his family, the decision was made to transition the patient to comfort care measures and he was transferred to the medical ward. He expired later that evening due to respiratory arrest.

Figure 6

Computed tomography image demonstrating filling defect in SVC distal to central venous port tip (arrow). SVC, superior vena cava

DISCUSSION

Our case represents a novel report in the medical literature demonstrating the utility of POCUS in the ED as the diagnostic modality of bilateral IJV thromboses. An added benefit of POCUS was demonstrated in our case – the directed guidance of venous access to the appropriate, patent femoral vein, which allowed treatment and resuscitation of the patient. Upper extremity IV access was non-functional in this patient due to obstruction from the SVC thrombosis, but the IVC was found to be patent on US as well as the femoral vein distal, which was cannulated using real-time ultrasound guidance.

SVC syndrome with unilateral IJV thrombosis is a rare occurrence, with bilateral IJV thromboses being rarer still.13 Literature searches via PubMed, Google Scholar, Cochrane Review, and Ovid using the terms “bilateral internal jugular vein thrombus,” “bilateral internal jugular vein thrombosis,” and “bilateral internal jugular vein thromboses” revealed multiple case reports demonstrating diagnosis of the thrombus via CT, MRI and US; however, none of the articles reported ED POCUS as the diagnostic modality. Few cases mentioned US as the initial diagnostic modality and these were radiologist-performed inpatient studies.14

Risk factors for thrombosis of the SVC include a history of malignancy, trauma, recent surgery, central venous access, retropharyngeal or deep space neck infections, hypercoagulability or known existing thrombi, and polycythemia. The more rapid the compression of the vessel, the more quickly symptoms occur due to lack of collateral vessel development. Physical exam findings of SVC syndrome most commonly include facial swelling with venous engorgement of the neck, trunk and upper extremities, dyspnea, orthopnea, cough, headache, nausea, and dizziness. Other complaints include a palpable cord or mass, fever, chest pain, visual disturbances, or seizures.15–19 Upper body cyanosis tends to be a late and ominous sign. Possible complications include pulmonary embolus, thrombophlebitis, airway edema, pseudotumor cerebri, superior sagittal sinus thrombosis, coma, and death.

Many diagnostic modalities exist including US, CT, magnetic resonance imaging, and contrast venography. CT is the gold standard and is the confirmatory radiographic modality of choice.20 As seen in this case, in the hands of an appropriately trained emergency physician, POCUS identified the extensive thromboses and helped plan the course of action for vascular access in this critically ill patient (femoral venous access). This information was timely and invaluable in the resuscitation of this patient who was too sick to travel to radiology for consultative imaging. Additionally, a number of other bedside ultrasounds were performed including an echocardiogram and an EFAST exam, giving critical information about cardiac function, volume status, and abdominal free fluid – all within minutes of arrival. In our patient, POCUS proved to be an invaluable tool.

Treatment typically consists initially of supportive care, head elevation, rest, supplemental oxygen, anticoagulation with the consideration of thrombolytics, clot retrieval. Some have advocated the use of diuretics and glucocorticoids. Identifying and treating the underlying cause, such as radiation and/or chemotherapy for malignancy, or antibiotics for underlying infection or thrombophlebitis, is also critical.15–19 All unnecessary catheters or other thrombogenic foci should be removed.

In summary, the rare occurrence of SVC syndrome due to thrombosis of the SVC is most commonly associated with vein cannulation, surgery, and malignancy. Although the SVC itself may be difficult to image with US, the diagnosis can be inferred readily at the bedside in the hands of the emergency physician, as evidenced in this case by identification of bilateral IJ and axillary thromboses. Though operator-dependent, POCUS is becoming an increasingly available and used resource. As more providers become adept at performing these exams in both stable and unstable patients, our hope is that patient safety and outcomes correspondingly improve.

Footnotes

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Aaron Birch, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, Madigan Army Medical Center, 9040 Fitzsimmons Ave, Tacmoa, WA 98431. Email: asbirch@gmail.com. 9 / 2014; 15:715 – 718

Submission history: Revision received October 9, 2012; Submitted May 29, 2014; Accepted June 10, 2014

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not represent the official views of the Department of Defense or Army Medical Department.

REFERENCES

1 Cardiopulmonary syndromes. National Cancer Institute website. ;

2 Gucalp R, Dutcher J Oncologic emergencies. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 2005; :575-576

3 Ahmann FR A reassessment of the clinical implications of the superior vena caval syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 1984; 2:961-9

4 Hassikou H, Bono W, Bahiri R Vascular involvement in Behçet’s disease. Two case reports. Joint Bone Spine. 2002; 69:416-8

5 Matsuura J, Dietrich A, Steuben S Mediastinal approach to the placement of tunneled hemodialysis catheters in patients with central vein occlusion in an outpatient access center. J Vasc Access. 2011; 12:258-61

6 Gbaguidi X, Janvresse A, Benichou J Internal jugular vein thrombosis: outcome and risk factors. QJM. 2011; 104:209-19

7 Dashti SR, Nakaji P, Hu YC Styloidogenic jugular venous compression syndrome: diagnosis and treatment: case report. Neurosurgery. 2012; 70:E795-9

8 Jayaraman MV, Boxerman JL, Davis LM Incidence of Extrinsic Compression of the Internal Jugular Vein in Unselected Patients Undergoing CT Angiography. Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;

9 Braun IF, Hoffman JC, Malko JA Jugular venous thrombosis: MR imaging. Radiology. 1985; 157:357-60

10 Lordick F, Hentrich M, Decker T Ultrasound screening for internal jugular vein thrombosis aids the detection of central venous catheter-related infections in patients with haemato-oncological diseases: a prospective observational study. British Journal of Haematology. 2003; 120:1073-1078

11 Modayil PC, Panthakalam S, Howlett DC Metastatic Carcinoma of Unknown Primary Presenting as Jugular Venous Thrombosis. Case Reports in Medicine. 2009;

12 Nagdev AD, Merchant RC, Tirado-Gonzalez A Emergency department bedside ultrasonographic measurement of the caval index for noninvasive determination of low central venous pressure. Ann Emerg Med. 2010; 55:290-5

13 Wang S, Raio C, Nelson M Bilateral internal jugular vein thrombosis. J Clin Ultrasound. 2011; 3:161-162

14 Panzironi G, Rainaldi R, Ricci F Gray-scale and color Doppler findings in bilateral internal jugular vein thrombosis caused by anaplastic carcinoma of the thyroid. J Clin Ultrasound. 2003; 31:111-5

15 Ugras-Rey S, Watson M Selected oncologic emergencies. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 2010; :1592-1594

16 Blackburn P Emergency complications of malignancy. Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 2004; :1363-1365

17 Armstrong BA, Perez CA, Simpson JR Role of irradiation in the management of superior vena cava syndrome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1987; 13:531-9

18 Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW The superior vena cava syndrome: clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine (Baltimore). 2006; 85:37-42

19 Blalock A, Cunningham RS, Robinson CS Experimental production of chylothorax by occlusion of the superior vena cava. Ann Surg. 1936; 104:359-64

20 Nickloes TA Superior vena cava syndrome. Medscape website. ;