| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Ryan P. Offman, DO | Mercy Health Partners, Muskegon, Michigan |

| Ryan M. Spencer, BA | Michigan State University College of Osteopathic Medicine, East Lansing, Michigan |

Introduction

Case report

Discussion

ABSTRACT

We present an interesting case of a patient with a previously known diaphragmatic hernia in which the colon became incarcerated, ischemic and finally perforated. She had no prior history of abdominal pain or vomiting, yet she presented with cardiovascular collapse. She was quickly diagnosed with a tension pneumothorax and treated accordingly. To our knowledge, this is the only case report of a tension pneumothorax associated with perforated bowel that was not in the setting of trauma or colonoscopy.

INTRODUCTION

Tension pneumothorax and its associated symptoms of tachycardia, hypotension, and eventual cardiovascular collapse are caused by the condition in which the pressure within the pleural space exceeds that of atmospheric pressure. This arises as the result of a ‘one-way valve’ scenario where air and/or fluid is allowed to enter the pleural space but is prevented from escaping. Tension pneumothorax typically has been described as occurring in patients on ventilators in an ICU setting, patients who have undergone trauma or resuscitation attempts, and those with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive lung disease.1 Other causes of tension pneumothorax are much more rare. Here we describe a unique case of atraumatic tension pneumothorax in a 50-year-old woman in the presence of an empyema secondary to perforation of an incarcerated segment of large bowel through a diaphragmatic hernia.

CASE REPORT

A 50-year-old female with a past medical history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, gastroesophageal reflux disease, paraesophageal gastric hernia, diaphragmatic hernia, and sickle cell trait presented to the emergency department (ED) with acute onset left-sided pleuritic chest pain and severe dyspnea. Relevant past surgical history includes Nissen fundoplication and appendectomy. Upon her arrival she was hemodynamically unstable with a heart rate of 162 beats per minute, blood pressure 75/62, and respiratory rate of 36 per min. Her oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

The patient was seen immediately. Upon initial examination she was noted to be in severe respiratory distress and could not speak more than one or two words between breaths. While attempting to obtain an initial history from the patient her BP began to drop further and she became more tachycardic. Monitor revealed continued sinus tachycardia with no ectopy. Upon auscultation it was noted that breath sounds were completely absent in the left hemithorax. Bedside ultrasound was immediately available and showed an abnormal pleural line, lack of comet-tail artifacts, and absence of lung sliding motion. This was felt to be consistent with pneumothorax. Due to her worsening cardiovascular instability it was decided that there was not sufficient time to obtain a portable chest radiograph and emergent needle thoracostomy was performed. After applying betadine solution to the overlying skin, a 14-gauge intravenous catheter was inserted in the left second rib interspace in the mid-clavicular line. Immediately a large release of air was appreciated. The patient’s BP increased from 63 systolic to 100 systolic and her heart rate began to decrease. Additionally, she was no longer exhibiting signs of respiratory distress as she was much less tachypneic and no longer using accessory muscles. The patient now demonstrated appreciable, however diminished, breath sounds on the left. Of note, this was the only intervention given to this patient at this time. At this point, the patient had not yet received any fluid resuscitation, vasoactive medications, nor antiarrhythmics.

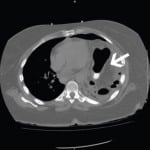

At that point it was felt that the patient was stable enough to obtain a chest radiograph. The radiograph showed some residual pneumothorax but also showed what appeared to be bowel in the left hemithorax (Figure 1). Lung markings could not be visualized 3 centimeters from the apex, although the exact size could not be determined due to overlying bowel. The radiologist’s report noted that the splenic flexure of the colon was herniated through the left hemidiaphragm. There was some aeration in the left upper lobe of the lung, the remainder of the left hemithorax was opacified. Cardiothoracic surgery was consulted, reviewed the chest radiograph and made the recommendation to replace the needle thoracostomy with a Heimlich valve to temporize the patient as we obtained an axial computed tomography (CT). After placing the Heimlich valve, a CT of the chest was obtained and showed a left diaphragmatic hernia with an intrathoracic loop of colon along with a loculated hydropneumothorax suspicious for empyema (Figure 2). This was compared to a CT from 12 days prior when she presented to the ED with abdominal pain and vomiting. The previous scan showed no evidence of incarceration of the bowel loop or the presence of an empyema. She had been following the diaphragmatic hernia with a surgeon on an outpatient basis. On that visit, her symptoms resolved and was discharged. She returned 2 days prior to this presentation with posterior thoracic pain. At that time, chest radiograph was obtained and showed the known hernia but no acute process, specifically no pneumothorax. She was felt to have musculoskeletal pain and was once again discharged. However, the CT scan obtained on the current visit showed an increased amount of colon within the thorax and the colon appeared to be significantly more distended when compared to the prior CT. This was suspicious for incarceration of the colon.

Figure 1. Portable chest radiograph obtained after needle thoracostomy, demonstrating near complete opacification of the left hemithorax with the presence of bowel loop.

Figure 2. Axial computed tomography scan of the chest, demonstrating near complete atelectasis of the left lung along with a loculated hydropneumothorax with multiple air pockets, suggestive of empyema.

The patient continued to remain hemodynamically stable while in the ED. Her surgeon that she was seeing regarding the diaphragmatic hernia was contacted and came to see her in the ED. Upon reviewing the radiograph and CT results, plans were made to take the patient to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy. This revealed a 3.5 cm diaphragmatic defect approximately 3 cm lateral to the esophageal hiatus through which a 10 cm segment of transverse colon was incarcerated. The segment of incarcerated transverse colon appeared ischemic and there was a 2 mm perforation. General surgery could not reduce the hernia. Therefore, cardiothoracic was called in to perform a thoracotomy and radial incision of the diaphragm “because of the narrowness of the diaphragmatic hernia.” Bowel, as well as omentum, was found to be “edematous and matted,” and was reduced and passed into the abdomen. No frank pus or stool was observed in the thoracic or peritoneal cavities. The ischemic segment of bowel was resected to healthy colon both proximally and distally and a side-to-side anastomosis was created. A chest tube was inserted into the left posterior thoracic cavity and the diaphragmatic defect was repaired.

Cultures of serosanguineous secretion from the chest tube showed growth of Escherichia coli and Enterococcus Avium. She was placed on antibiotic therapy. She gradually regained bowel function and continued to improve quite well. She was discharged after a 9-day hospital stay in good condition.

DISCUSSION

Although we did not have the luxury to obtain a confirmatory radiograph prior to intervention, it is felt that the presenting absence of breath sounds cannot be attributed simply to the presence of bowel in the thoracic cavity. This patient presented with cardiogenic shock. This was proven through response to initial therapy and subsequent radiologic and laboratory testing. Workup revealed no other etiologies of acute cardiogenic shock and she certainly revealed tension physiology upon initial presentation which responded immediately to relief of pressure within the chest cavity. Moreover, had her presentation been solely due to displacement of bowel, she would have clinically worsened with the introduction of free air into her chest. Although we were surprised at the small volume of the pneumothorax after initial stabilization, we postulate that very little external air was needed to provide tension physiology with so much of her hemithorax occupied by incarcerated bowel. In addition, her bowel was found to be grossly ischemic ruling out the possibility that her pulmonary findings were due to a sudden worsening of the size of the hernia. Although radiology felt CT images to be consistent with empyema, surgical findings did not support this. However, CT appearance is notoriously inaccurate when characterizing pleural fluid.2 Retrospectively, we are left with no other reason for her cardiovascular collapse other than tension pneumothorax from her ischemic, perforated bowel.

While there have been several cases reported in the literature of tension pneumothorax due colon perforation associated with colonoscopy, the patient described in this case did not undergo any recent endoscopic procedures.3,4 Additionally, there have been case reports of tension pneumothorax in the setting of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia.5,6 However, the patient described in this case did not have any history of either remote or recent traumatic injury.

Here we have reported an unusual case of tension pneumothorax in the setting of a chronic diaphragmatic hernia with perforation of incarcerated transverse colon and subsequent formation of an empyema. The cause of the patient’s diaphragmatic defect is not completely apparent, although it is unlikely to be a congenital (Bochdalek or Morgagni) hernia as it was not noticed during prior surgical procedures or imaging studies in the distant past. As previously stated, it had been discovered prior to this described ED visit that the patient in this case had a diaphragmatic hernia with the presence of colon in the left hemithorax. However, imaging studies confirmed that the colon was not incarcerated and that surgical intervention was not immediately necessary at that time. She had been following the hernia with her surgeon on an outpatient basis with repeat imaging studies as needed. Even though the hernia had remained stable for quite some time, upon incarceration and perforation, she rapidly decompensated. This case illustrates that, while rare, formation of a tension pneumothorax is an important consideration when following patients with known diaphragmatic hernia. Moreover, their presentation is unlikely to be typical of incarcerated bowel.

Footnotes

Address for Correspondence: Ryan Offman, DO, Emergency Health Partners-Muskegon, 1500 E. Sherman Blvd, MI 49444 Email: dr.ryanoffman@gmail.com 3 / 2014; 15:142 – 144

Submission history: Revision received August 4, 2013; Submitted September 23, 2013; Accepted October 3, 2013

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. MacDuff A, Arnold A, Harvey J. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society pleural disease guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010;65:ii18-ii31.

2. Abramowitz Y, Simanovsky N, Goldstein MS, Hiller N. Pleural effusion: Characterization with CT attenuation values and CT appearance. Am J Roentgenol. 2009; 192:618-23.

3. Ball CG, Kirkpatrick AW, Mackenzie S, et al. Tension pneumothorax secondary to a colonic perforation during diagnostic colonoscopy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2006; 36:478-480.

4. Ignjatovic M, Jovic J. Tension pneumothorax, pneumoretroperitoneum, and subcutaneous emphysema after colonoscopic polypectomy: a case report and review of the literature. Lagenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:185-189.

5. Ramdass MJ, Kamal S, Paice, et al. A Traumatic diaphragmatic herniation presenting as a delayed tension faecopneumothorax. Emerg Med J. 2006; 23:e54.

6. Kelly J, Condon ET, Kirwan WO, et al. Post-traumatic tension faecopneumothorax in a young male: case report. World J Emerg Surg. 2008;3:20.