| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Stephen Zanoni, MD | Naval Medical Center San Diego, Department of Emergency Medicine, San Diego, California |

| Gerald Platt, MD | Naval Medical Center San Diego, Department of Emergency Medicine, San Diego, California |

| Shaun Carstairs, MD | Naval Medical Center San Diego, Department of Emergency Medicine, San Diego, California |

| Mark Hernandez, MD | Scripps Hospital Chula Vista, Department of Emergency Medicine, Chula Vista, California |

Introduction

Case report

Discussion

ABSTRACT

Patients who present with recurrent syncope are at risk for having underlying conduction disease, which may worsen if not promptly recognized and treated. We describe a patient who initially presented to a Mexican clinic with recurrent syncope and an electrocardiogram that showed complete heart block. After being transferred to our emergency department, he deteriorated into complete ventricular asystole with preserved atrial function and required placement of a transvenous cardiac pacemaker.

INTRODUCTION

Syncope is a common chief complaint in the emergency department (ED), with underlying conduction disease as a rare but serious possible cause. Ventricular asystole with preserved atrial function is a rare presenting rhythm in the ED and is not commonly reported as a cause of syncope.1 We present a case of a patient who presented with syncope that progressed to altered mental status due to complete ventricular asystole.

CASE REPORT

A 68-year-old male was transferred to our ED in Southern California via ambulance from the United States (U.S.)-Mexico border after being initially assessed in a Mexican medical clinic. Paramedics reported that he had presented to the clinic because of recurrent fainting episodes witnessed by his family in Mexico. According to the ambulance personnel, his electrocardiogram (ECG) performed at the clinic demonstrated third-degree atrioventricular block. The ECG that was performed in Mexico was not transported with the patient and was therefore not available for review.

While at the Mexican clinic, the patient reportedly decompensated and had an episode of altered mental status with what were described as “unstable” vital signs. The full details of what occurred were not available, but it was reported that the practitioners at the clinic initiated transcutaneous pacing and administered an unknown sedation medication and started the patient on a dopamine infusion. He was then transferred to the U.S.-Mexico border via ambulance. Just prior to arrival at our hospital, the patient’s intravenous access was lost in the ambulance, and his transcutaneous pacing became ineffective. Upon arrival in the ED, he was lethargic and could not follow commands. He was cyanotic, had a weak but palpable pulse, shallow respirations, and a native heart rate of 30 beats/min with no capture by the pacemaker. We immediately increased the amperage of his transcutaneous pacer, which resulted in cardiac capture, and the patient developed a palpable pulse of 70 beats/min with improvement of his blood pressure to 114/53 mmHg. His core temperature was normal. The patient’s neurological exam improved as he now had spontaneous movement of all 4 extremities. His initial oxygen saturation was 88%, which improved with supplemental oxygen administered via bag valve mask. As his saturations improved, he began to be able to follow commands. However, he became agitated and combative and endotracheal intubation with rapid sequence induction was performed.

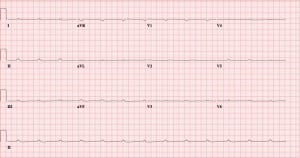

Following intubation and mechanical ventilation, his oxygen saturation improved to 100%. An ECG obtained while the pacer was turned off (Figure) revealed ventricular asystole with preserved atrial function. Emergent cardiology consultation was obtained for transvenous pacer placement. Secondary assessment revealed no jugular venous distention, normal heart sounds without murmurs and clear lungs bilaterally. The abdomen was soft and non-distended. Extremities revealed resolving cyanosis without edema.

Figure. Electrocardiogram demonstrating complete ventricular asystole.

The patient’s daughter was contacted and arrived after intubation and initial stabilization. She reported the patient took atenolol for hypertension, smoked “heavily,” and was recently started on bupropion for smoking cessation. He had no known prior cardiac history. The prior week, while vacationing in Mexico with family, he had increasing weakness, shortness of breath, and several syncope episodes. According to the daughter, he had no recent chest pain, nausea, vomiting, or focal weaknesses. There was no history of trauma. She stated he had no recent increases in his medication dosages, and he had forgotten to bring his atenolol with him to Mexico.

Arterial blood gas following intubation revealed a pH of 7.13, pCO2 of 45 mmHg, pO2 of 422 mmHg, and a lactate of 14.2mmol/L. Bedside glucose was 220 mg/dL. Cardiac enzymes revealed a troponin T of 0.31μg/L with a normal creatine kinase. Complete blood count was unremarkable. His comprehensive metabolic panel was significant for an anion gap of 24 with normal electrolyte levels. His potassium was normal at 4.0 mEq/L. His creatinine and blood urea nitrogen were 2.3 mg/dL and 28 mg/dL respectively. Urine drug screen and serum alcohol were negative. The cardiologist’s official read of the ECG was complete ventricular asystole with preserved atrial function at a rate 100 beats per min. No p-wave enlargement was appreciated. Intervals, axis, and ST morphology could not be assessed due to the underlying rhythm.

A sodium bicarbonate infusion was started and the patient was taken to the interventional cardiology suite for transvenous pacer placement. Afterward, he was admitted to the intensive care unit. On hospital day 2, a transthoracic echocardiogram was significant for mild mitral regurgitation and mild left ventricular hypertrophy. He was successfully extubated on hospital day 3, had intact mental status, and was able to consent for placement of implantation of a permanent dual chamber pacemaker. He was discharged after successful completion of the procedure with close follow up. His cardiac enzymes trended downward from initial presentation, and he did not have a percutaneous coronary angiogram performed during his inpatient stay. He was diagnosed with complete atrioventricular block due to advanced conduction disease with no reversible etiology. Amiodarone or other anti-dysrhythmic medications were not administered during his stay.

DISCUSSION

Ventricular asystole with preserved atrial function is an extreme consequence of conduction disease, with a poor prognosis if not treated emergently. In the case described above, no reversible etiology was discovered and no medication or illicit substance was suspected to be the cause. The patient did have a prescription for atenolol, but he was not recently taking it, making beta-blocker poisoning unlikely as an etiology. Other previously reported causes include: digitalis therapy in the setting of hypokalemia,2 Lyme disease,3 increased vagal tone or vagal stimulation,1,4,5 and blunt chest trauma resulting in acute tricuspid insufficiency.6,7 In one case, the rhythm occurred in a 46-year-old male presenting with chest pain and no known coronary disease one minute following nitroglycerin therapy.8

In previous case reports, the rhythm either self-terminated or was readily stabilized by appropriate pacing therapies. Interestingly, manual external pacing at a rate of 52 beats per minute generated a blood pressure of 108/62 mmHg in a patient who experienced this rhythm during pulmonary artery catheter placement.9 In another case report, the patient was administered 500 mg intravenous of aminophylline and reverted to sinus rhythm shortly after without other cardiac pacing modalities.7

In our patient, no reversible cause for his complete heart block was found. His electrolytes and Lyme studies were normal. Medication overdose was unlikely given his noncompliance. His echocardiogram was negative for major structural abnormality. However, our patient did not have a non-contrast head computed tomography or a PCA performed. These studies, in particular the PCA, may have aided in discovering a potential cause. Regardless of the underlying etiology, sustained ventricular asystole is a rhythm that requires immediate intervention with external cardiac pacing and subsequent placing of implantable cardiac pacemaker.

Footnotes

Address for Correspondence: LT Stephen Zanoni, MD, Naval Medical Center San Diego, Department of Emergency Medicine, 34800 Bob Wilson Dr., San Diego, CA 92134. Email: steve@thezanonis.com. 3 / 2014; 15:149 – 151

Submission history: Revision received July 8, 2013; Submitted September 23, 2013; Accepted October 28, 2013

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense or the United States Government.

REFERENCES

1. Yerg JE, Seals DR, Hagberg JM, et al. Syncope secondary to ventricular asystole in an endurance athlete. Clin Cardiol. 1986; 9:220-222.

2. Leon-Sotomayor L, Myers WS, Hyatt KH, et al. Digitalis-Induced ventricular asystole treated by an intracardiac pacemaker. Am J Cardiol. 1962;10:298-301.

3. Weissman K, Jagminas L, Shapiro MJ. Frightening dreams and spells: a case of ventricular asystole from Lyme disease. Eur J Emerg Med. 1999;6:397-401.

4. Korantzopoulos P, Grekas G, Lampros S, et al. Markedly prolonged atrioventricular block with ventricular asystole during sleep. South Med J. 2009;102:870-874.

5. Schuurman PR. Ventricular asystole during vagal nerve stimulation. Epilepsia. 2009;50:967-968.

6. Wang NC. Immediate pacing for traumatic complete atrioventricular block and ventricular asystole. Am J Med. 2012; 123:e3-4.

7. Khoury MY, Moukarbel GV, Obeid MY, et al. Effect of aminophylline on complete atrioventricular block with ventricular asystole following blunt chest trauma. Injury. 2001;32:335-338.

8. Younas F, Janjua M, Badshah A, et al. Transient complete heart block and isolated ventricular asystole with nitroglycerin. J Cardiovasc Med. 2012;13:533-535.

9. Chan L, Reid C, Taylor B. Effect of three emergency pacing modalities on cardiac output in cardiac arrest due to ventricular asystole. Resuscitation. 2002;52:117-119.