| Author | Affiliation |

| Katherine R. Harter, MD, MPH | Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Angeles County + USC Medical Center, Los Angeles, California |

| Sanjay Bhatt, MD | Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Angeles County + USC Medical Center, Los Angeles, California |

| Hyung T. Kim, MD | Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Angeles County + USC Medical Center, Los Angeles, California |

| William K. Mallon, MD | Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Angeles County + USC Medical Center, Los Angeles, California |

Introduction

Case Report

Results

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

ABSTRACT

We report the case of a 33-year-old woman returning from Haiti, presenting to our emergency department (ED) with fever, rash and arthralgia. Following a broad workup that included laboratory testing for dengue and malaria, our patient was diagnosed with Chikungunya virus, which was then reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for initiation of infection control. This case demonstrates the importance of the ED for infectious disease case identification and initiation of public health measures. This case also addresses public health implications of Chikungunya virus within the United States, and issues related to the potential for local spread and autochthonous cases.

INTRODUCTION

Fever in the returned traveler can be a diagnostic challenge. Emergency medicine providers must consider a broad differential diagnosis, which includes infectious diseases native to the areas of travel. Often this differential includes diseases not routinely considered and even at times includes a diagnosis new to the clinical team. In this report, we review a case of a woman complaining of high fever, joint pain, and rash who presented to our urban emergency department (ED) in Los Angeles County shortly after returning from abroad.

CASE REPORT

On June 13, 2014, a 33-year-old Caucasian woman presented to the ED. She complained of one week of fever, joint pain and rapid development of a total body rash. She did note recent travel to visit friends in Port au Prince, Haiti from May 29, 2014, to June 7, 2014. During her trip she noted multiple mosquito bites, and while she had initially been taking antimalarials, due to nausea she stopped taking them shortly after her arrival. Her vaccination history included immunizations to typhoid, hepatitis B and tetanus. On June 6, 2014, she began to feel nonspecific malaise. Concerned about her symptoms, she decided to leave earlier than previously planned. Prior to departure she noted that her friends, now local to Haiti, were having similar symptoms of malaise and fever.

On June 7, 2014, she returned to the United States and noted a fever of 102.0°F. Additionally, she noted a rash over her trunk and extremities. She was initially evaluated at an outside ED on day 2 of her illness. At that time her laboratory workup revealed a leukocyte count of 5900, hemoglobin 12.8 g/dL, hematocrit of 37.1%, and platelet count of 148000/m3. The remainder of her laboratory work-up, including basic metabolic panel, hepatic function panel and coagulation studies, were all within normal limits. She was diagnosed with cellulitis and sent home on trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and clindamycin. After one day of antibiotics, due to nausea she discontinued her medications. She also noted that her fever began to improve. On day 6 of her illness, she noted a returning fever, further spread and intensification of her rash, and diffuse joint pain.

She presented to our ED on day 7 of her illness with a temperature of 100.3°F, a heart rate between 110 and 120 beats per minute, and was otherwise hemodynamically stable and well appearing. Her physical exam was notable for a diffuse blanching maculopapular rash covering her trunk, extremities and face. She complained of joint pain and swelling but had no appreciable effusions; she had full active strength and range of motion in all extremities, with otherwise benign neurologic, cardiopulmonary and abdominal exams.

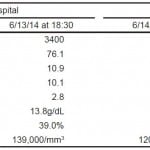

Given her recent travel history, thick and thin malaria smears were sent along with basic laboratory studies. Her leukocyte count resulted as 3400 (neutrophils= 76.1%, lymphocytes= 10.9%, eosinophils= 2.8%, monocytes= 10.1%), hemoglobin 13.8 g/dL, hematocrit of 39%, and platelet count 139000/mm3. Her urinalysis, basic metabolic panel, and hepatic function panel were also within normal limits. Her human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) screen was negative. She remained stable throughout the ED course and was placed in the ED observation unit for further monitoring. There, her BinaxNow malaria antigen detection test and Giemsa stain thin and thick smears were reported negative.

While in the ED observation unit she remained hemodynamically stable. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) was contacted for further recommendations and for disease reporting. Serologic studies were sent for the evaluation of both dengue and Chikungunya viruses. Additional sets of labs were obtained as shown in table below. She was discharged later that afternoon.

The Chikungunya IgG and IgM serologic studies were reported positive. These positive serology studies were reported to the California Department of Public Health who responded with a notification bulletin to local health facilities and vector control in the patient’s neighborhood, which included spraying her neighborhood for Aedes mosquitoes. On follow-up one week after discharge, our patient reported that the majority of her symptoms had resolved by day 10 of her illness. She did endorse persistent mild joint pain in her extremities, much improved from her initial presentation to our ED. Three weeks following her return from Haiti, she endorsed complete resolution of all symptoms, including cessation of arthralgia.

Table. Laboratory work up throughout emergency department visits of patient with chikungunya fever: complete blood count trend.

DISCUSSION

Given our patient’s recent travel history, the initial differential diagnosis included tropical infections endemic to Haiti. The differential included hepatitis, malaria, primary HIV, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), typhoid fever, rickettsia, leptospirosis, as well as more common etiologies of fever and rash seen in the ED, including group A streptococcus and drug reactions. Upon discussion with the CDC, the differential extended to include dengue and chikungunya fever.

Dengue and chikungunya fever have similar clinical features, are both spread by the Aedes mosquitos, and can present with a wide range of symptoms, ranging from those of a benign febrile illness to those with severe neurologic and hemorrhagic complications that can result in shock and death. Clinical differentiation of the chikungunya virus from the dengue virus can be difficult; generally arthralgia is more commonly seen in chikungunya fever while myalgia and thrombocytopenia (platelets <118,000/mm3) are more common to dengue fever.1,2 Both illness may have a rash, and both may have a saddleback fever profile. A tourniquet test is more likely to be positive in dengue fever; however, this is not consistently seen in the literature.3

Chikungunya fever is primarily a mosquito-borne alpha-virus endemic to Africa.4 Humans are the primary viral host and the global spread of the virus occurs when infected humans travel between regions that both support competent Aedes mosquitoes. The Aedes Aegypti and Aedes Albopictus mosquitoes are vectors for both dengue and chikungunya viruses; these mosquitoes were initially thought to be endemic to the tropics; however, they are now known to survive in the Americas and some parts of the United States (U.S.)4,5 Additionally, recently studied point mutations have resulted in increased infectivity and transmission of the virus.5,6 Thus, both the breadth of human travel and genetic variation in the virus itself are promoting the spread of the virus.

The viral incubation is quite short, and returned travelers who develop a fever more than 7-10 days after their return are unlikely to have either dengue or chikungunya infections. The incubation period ranges from 2-4 days and symptoms generally present between 3-7 days after the initial mosquito bite.1,7,8 Serologic surveys indicate that over 75% of those with antibodies to the chikungunya virus have had a symptomatic infection, thus supporting the belief that most of those infected become symptomatic.2 The spectrum of clinical features of chikungunya fever ranges from asymptomatic patients to those who experience hemorrhage and death.

The most common symptoms are fever and polyarthralgia. Joint symptoms, which are reported in over 85% of symptomatic patients, are usually symmetric and more commonly occur in the distal joints, most frequently in the hands and ankles.8,9 Additional symptoms may include cutaneous manifestations, commonly a maculopapular rash over the face, trunk and extremities, headaches, myalgias, conjunctivitis, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.2,8 Severe complications are rare, but include uveitis, retinitis, myocarditis, hepatitis, nephritis, bullous skin lesions, hemorrhage, and neurologic complications, including encephalitis, Guillain-Barre syndrome and cranial nerve palsies.1,2,8,10-12 Patients more likely to experience severe outcomes include neonates, adults over the age of 65, and those with an underlying medical condition or immunodeficiency.2,8

In acute infection symptoms generally resolve within 14 days, though occasionally symptoms can persist for many years. Polyarthralgia is the most common chronic manifestation of Chikungunya fever; the most common factors associated with prolonged joint pain or stiffness are pre-existing arthralgia, underlying rheumatologic disorders, female sex, and increased age, though data vary by population studied.8,9,13

Chikungunya fever is often diagnosed clinically, especially in resource-limited settings. General laboratory workup often reveals lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, an elevated creatinine, and elevated hepatic transaminases.1,2,8 Specific laboratory tests do exist to confirm diagnosis of Chikungunya virus and are available through the CDC and several state health departments. Diagnosis through the viral culture can detect the virus within the first three days of illness. RT-PCR can detect viral RNA in the first eight days of illness, and serology can detect IgM and IgG antibodies towards the end of the first week of illness.1

The mainstay of treatment revolves around symptomatic management. As noted above, given the similarities in initial clinical presentation, shared geographic distribution, and Aedes mosquito disease vector for the Chikungunya and dengue viruses, the CDC recommends that all suspected cases of Chikungunya be managed as dengue fever initially; this is particularly true as dengue fever has increased morbidity and mortality.1 Additionally, they recommend against the use of aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs given the risk of associated hemorrhage in patients with dengue fever.1

Prevention strategies for the Chikungunya virus primarily focus on minimizing exposure to mosquitos and local vector control efforts. There are no specific vaccinations or medications for the prevention or treatment of Chikungunya. In general, epidemics of Chikungunya worldwide have been limited to areas of competent Aedes mosquitos, and until recently no local transmission was noted in or near the U.S. With recent outbreaks in the Caribbean and South America, as well as the first documented cases of autochthonous transmission in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, it will be important to consider chikungunya in the differential of a patient with recent travel, fever, arthralgias and/or a rash.14

California has had seven confirmed cases of Chikungunya fever in 2014, all found in travelers returning to or visiting the U.S.14 In addition, the California Department of Public Health released a notice on June 13, 2014 that competent Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes have been found in several California cities, including in Los Angeles County, where this case presented, making the possibility of local transmission more realistic as travelers return from endemic countries.15

CONCLUSION

Chikungunya fever typically presents within 2-4 days of infection, and is spread primarily from mosquito to human. Until recently cases of Chikungunya fever in or near the U.S. were noted only in travelers returning to or visiting from regions with current epidemics. Chikungunya and dengue fever share many clinical aspects and in suspect patients both diseases should be tested. As of May 30, 2014, the first case of autochthonous transmission was noted in Puerto Rico, and since that time more cases have been reported. With the recent notice regarding competent mosquitoes in California and other areas of the U.S., the index of suspicion must be raised and the differential broadened to include Chikungunya fever, especially as it can lead to the initiation of public health interventions such as vector control.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Rick McPheeters, DO

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Katherine Harter, The Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Angeles County and USC Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, USC Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, 1200N. State Street, Los Angeles, CA 90033. Email: krharter@gmail.

Submission history: Submitted July 11, 2014; Accepted August 15, 2014

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

- CDC. Chikungunya information for healthcare providers. CDC Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/chikungunya/pdfs/CHIKV_Clinicians.pdf. Accessed Jul 4, 2014.

- Staples JE, Breimen RF, Powers AM. Chikungunya fever: an epidemiological review of a re-emerging infectious disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:942-8.

- Nimmannitya S, Halstead SB, Cohen SN, et al. Dengue and chikungunya virus infection in man in Thailand, 1962–1964. Observations on hospitalized patients with hemorrhagic fever. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1969;18:954–71.

- Fischer M, Staples JE. Notes from the field: Chikungunya virus spreads in the Americas – Caribbean and South America 2013-2014. MMWR. CDC Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6322a5.htm. Accessed Jul 4, 2014.

- Pialoux G, Gaüzère BA, Jauréguiberry S, et al. Chikungunya, an epidemic arbovirosis. Lancet Infec Dis. 2007;7(5):319-27.

- Vega-Rúa A, Zouache K, Girod R, et al. High level of vector competence of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus from ten American countries as a crucial factor in the spread of chikungunya virus. J Virol. 2014;88(11):6294-6306.

- Queyriaux B, Simon F, Grandadam M, et al. Clinical burden of chikungunya virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8(1):2-3.

- Thiberville SD, Moyen N, Dupuis-Maguiraga L, et al. Chikungunya fever: epidemiology, clinical syndrome, pathogenesis and therapy. Antiviral Res. 2013;99(3):345-70.

- Borgherini G, Poubeau P, Jossaume A, et al. Persistent arthralgia associated with chikungunya virus: a study of 88 adult patients on Reunion Island. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:469-75.

- Chandak NH, Kashyap RS, Kabra D, et al. Neurological complications of chikungunya virus infection. Neurol India. 2009;57(2):177.

- Wielanek AC, De Monredon J, El Amrani M, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome complicating a chikungunya virus infection. Neurology. 2007;69(22):2105-7.

- Das S, Sarkar N, Majumder J, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in a child with chikungunya virus infection. JPID. 2014;9(1):37-41.

- Dupuis-Maguiraga L, Noret M, Brun S, et al. Chikungunya disease: infection-associated markers from the acute to the chronic phase of arbovirus-induced arthralgia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1446.

- CDC. Chikungunya virus in the United States. ArboNET. CDC Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/chikungunya/geo/united-states.html. Accessed Jul 4, 2014.

- CDPH. Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. CDPH Web site. Available at http://www.cdph.ca.gov/HealthInfo/discond/Pages/Aedes-albopictus-and-Aedes-aegypti-Mosquitoes.aspx. Accessed Jul 4, 2014