| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Daryl K. Knox, MD | Mental Health and Mental Retardation Authority of Harris County, Comprehensive Psychiatry Emergency Program, Houston, Texas |

| Garland H Holloman, Jr, MD, PhD | University of Mississippi Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry, Jackson, Mississippi |

ABSTRACT

Issues surrounding reduction and/or elimination of episodes of seclusion and restraint for patients with behavioral problems in crisis clinics, emergency departments, inpatient psychiatric units, and specialized psychiatric emergency services continue to be an area of concern and debate among mental health clinicians. An important underlying principle of Project BETA (Best practices in Evaluation and Treatment of Agitation) is noncoercive de-escalation as the intervention of choice in the management of acute agitation and threatening behavior. In this article, the authors discuss several aspects of seclusion and restraint, including review of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services guidelines regulating their use in medical behavioral settings, negative consequences of this intervention to patients and staff, and a review of quality improvement and risk management strategies that have been effective in decreasing their use in various treatment settings. An algorithm designed to help the clinician determine when seclusion or restraint is most appropriate is introduced. The authors conclude that the specialized psychiatric emergency services and emergency departments, because of their treatment primarily of acute patients, may not be able to entirely eliminate the use of seclusion and restraint events, but these programs can adopt strategies to reduce the utilization rate of these interventions.

INTRODUCTION

A major focus of Project BETA (Best practices in Evaluation and Treatment of Agitation)1 is noncoercive de-escalation, with the goal being to calm the agitated patient and gain his or her cooperation in the evaluation and treatment of the agitation. Some healthcare providers may view forced medication, seclusion, and restraint as the safest and most efficient intervention for the agitated patient but are relatively unaware that these interventions are associated with an increased incidence of injury to both patients and staff. These injuries are both physical and psychological. In addition, the use of drugs for the purpose of restraint results in side effects that can be problematic. Both physical interventions and drugs for the purpose of restraint have short-term and long-term detrimental implications for the patient and the physician-patient relationship. Because of this, regulatory agencies and advocacy groups are pushing for a reduction in the use of restraint. However, there are clinical situations for which verbal and behavioral techniques are not effective and the use of seclusion and/or restraint becomes necessary to prevent harm to the patient and/or staff. When use of restraint and seclusion is unavoidable, there are measures that can be taken to mitigate some of the negative consequences that may result when such actions are taken.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has adopted Conditions of Participation for Hospitals. These same conditions have been endorsed by The Joint Commission (TJC). In doing so, the following definitions are used:

- Seclusion is the involuntary confinement of a patient alone in a room or area from which the patient is physically prevented from leaving. Seclusion may be used only for the management of violent or self-destructive behavior.2

- A restraint is any manual method, physical or mechanical device, material, or equipment that immobilizes or reduces the ability of a patient to move his or her arms, legs, body, or head freely.2

- A drug is considered a restraint when it is used as a restriction to manage the patient’s behavior or restrict the patient’s freedom of movement and is not a standard treatment or dosage for the patient’s condition.2

- Seclusion and restraint must be discontinued at the earliest possible time.2

- Within 1 hour of the seclusion or restraint, a patient must be evaluated face-to-face by a physician or other licensed independent practitioner or by a registered nurse or physician assistant who has met specified training requirements.2

Specified also are the following patient’s rights:

- Seclusion or restraint may be used only when less restrictive interventions have been determined to be ineffective to protect the patient, a staff member, or others from harm.2

- All patients have the right to be free from restraint or seclusion, of any form, imposed as a means of coercion, discipline, convenience, or retaliation by staff.2

- Restraint or seclusion may only be imposed to ensure the immediate physical safety of the patient, a staff member, or others.2

In addition to the requirement to conform to these regulations, there are medicolegal reasons to avoid seclusion and restraint. A National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors document on risk management concludes as follows:

“Every episode of restraint or seclusion is harmful to the individual and humiliating to staff members who understand their job responsibilities. The nature of these practices is such that every use of these interventions leaves facilities and staff with significant legal and financial exposure.

Public scrutiny of restraint and seclusion is increasing and legal standards are changing, consistent with growing evidence that the use of these interventions is inherently dangerous, arbitrary, and generally avoidable. Effective risk management requires a proactive strategy focused on reducing the use of these interventions in order to avoid tragedy, media controversy, external mandates, and legal judgments.”3

The purpose of this article is twofold. First, we will review information that supports the need to avoid physical restraint if at all possible. Second, we will provide guidelines for the use of seclusion and restraint when other methods fail. We will also offer recommendations to lessen the psychological impact on patients and staff that often ensues in the aftermath of a seclusion and restraint episode.

USE OF PHYSICAL RESTRAINT

There is much controversy regarding the use of restraints and seclusion. In 1994, Fisher4 reviewed the literature and concluded that restraint and seclusion were useful for preventing injury and reducing agitation and that it was impossible to run a program that dealt with seriously ill individuals without the use of these restrictive interventions. However, he did acknowledge that use of these interventions caused adverse physical and psychological effects on both staff and patients and pointed out that nonclinical factors, such as cultural biases, role perceptions, and attitude, are substantial contributors to the frequency of seclusion and restraint.

A review by Mohr et al5 concluded that the use of restraints puts patients at risk for physical injury and death and can be traumatic even without physical injury. Acknowledging the lack of empirical studies, they also concluded that physical injuries to patients were caused by a variety of complications from the use of physical restraint.

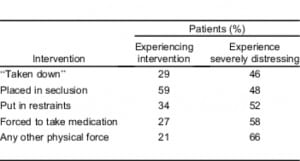

The Table shows several items from the data of a survey of 142 patients, using a questionnaire designed to identify the frequency of potentially harmful events and the associated psychological distress experienced by the patient. This clearly shows that commonly used interventions are traumatic to patients.6

If patients experience physical and psychological effects from restraints, what effects do healthcare providers experience when working with agitated patients? Healthcare workers are at a considerably higher risk for workplace violence than other professions. Nurses are at greater risk than physicians (2.19% vs 1.62%), but the risk is even greater for mental health professionals (6.82%).7 In a survey of 242 emergency department workers at 5 hospitals, approximately 48% had been physically assaulted.8 In a randomized sample of 314 nurses, 62.1% had been exposed to aggression by patients. Of these, 40% experienced psychological distress and 10% experienced moderate to severe depression.9 None of these studies looked at the injury occurring during attempted restraint. However, in a study of the prehospital, emergency medical services (EMS) setting, 4.5% of cases involved violence toward EMS personnel.10 When physical restraint was used in the prehospital setting, 28% involved assault on EMS personnel.11

Even if restraint and seclusion can prevent injury to patients and staff, a physical altercation with a patient can result in a variety of injuries to both, and these injuries could be avoided if effective ways were available to manage the patient without their use. This can happen, but it will require a change in attitude on the part of clinicians who work with agitated patients, as well as change in the staff development training and culture of the institutions in which they practice. In a summary report, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration states, “The culture must change from one in which seclusion and restraint are viewed as positive and therapeutic to one in which they are regarded as violent acts that result in traumatization to patients, observers, and others.”12 The following studies show that this is possible.

A public psychiatric inpatient service was able to reduce restraint without an increase in patient-to-patient assaults. There was an initial increase in patient-to-staff assaults but when the initial period was excluded, there was no statistical change.13

In a retrospective analysis of a large inner city hospital’s efforts to implement the mandates of CMS and TJC, Khadivi et al14 found a significant decrease in the use of restraints but an increase in assaults on patients and staff. However, they noted that “staff did not receive any specific training in the management of violent patients, which may have increased the rate of assaults on staff members and diminished their ability to reduce other-directed assaults.”

Another large study took place in 9 Pennsylvania state hospitals during an 11-year period. According to the authors, “the rate of seclusion decreased from 4.2 to 0.3 episodes per 1,000 patient-days. The average duration of seclusion decreased from 10.8 to 1.3 hours. The rate of restraint decreased from 3.5 to 1.2 episodes per 1,000 patient-days. The average duration of restraint decreased from 11.9 to 1.9 hours.” At the time of the study, 1 hospital had gone 2 years without using restraint; and, since 2005, the system as a whole, which provides more than 60,000 days of care per month, had used seclusion 19 times and restraints 143 times for a total of 160 hours. Data on staff injury indicated that staff members were not at increased risk of assault. The authors attributed part of the success to administration recognizing that “seclusion and restraint are not treatment modalities but treatment failures.” Other major reasons were changes in attitude, culture, and environment within the hospitals.15

Donat16 reviewed several initiatives aimed at reducing seclusion and restraint taken during a 5-year period at a public psychiatric hospital. These initiatives included “changes in the criteria for administrative review of incidents of seclusion and restraint, changes in the composition of the case review committee, development of a behavioral consultation team, enhancement of standards for behavioral assessments and plans, and improvements in the staff–patient ratio.” He applied a multiple regression analysis to the results and discovered that the most significant variable leading to the 75% reduction in seclusion and restraint incidents was “changes in the process for identifying critical cases and initiating a clinical and administrative case review.”

The above strategies for decreasing seclusion and restraint worked well in inpatient hospital environments, and there are several other reports on successful reduction of seclusion or restraint.17–20 However, it may be unrealistic to expect these results in a psychiatric emergency service (PES) or emergency department (ED) setting, as they differ in clinical structure, purpose, and length of stay from an inpatient hospital unit.

Zun,21 in a prospective study of complications of restraint use in emergency departments, found that use of restraints “is significantly higher than in an inpatient facility.” Hospital inpatient units are seldom as hectic as an ED or PES. In inpatient facilities, patients typically have a chance to develop rapport with staff over a period of days, and most units provide ample space and a place such as a bedroom for patients to retreat when unit activity becomes stressful. The volume of admissions and discharges from an inpatient unit occurs more sporadically than in an ED or PES, where there are constant admissions and discharges within a day, and the acuity level can be constantly high and intense. Arguably, these differences between the emergency setting and an inpatient unit make it less likely that episodes of seclusion and restraint can be eliminated totally in this setting. However, review of seclusion and restraint cases, including feedback to staff, and institutional changes in culture and attitude, can be important factors in reducing occurrence of these incidents in more acute settings.

In the introduction to a special session on seclusion and restraint, Busch22 states that programs for reduction of restraint have been successful without increasing the risk to staff. She asks, “Can we do a better job of preventing or de-escalating these situations so that we do not need to use seclusion, restraint, or emergency medication?” She points out that literature tells us that we can.

Even with these and other success stories, the use of seclusion and restraint is still a common practice. Seclusion is used as an intervention in 25.6% of emergency departments.23 In another survey of emergency departments, 30% of respondents used physical restraint alone and another 30% used physical restraint combined with pharmacotherapy.24

Ashcraft and Anthony25 state that successful seclusion and restraint reduction programs are based on strong leadership direction, policy and procedural change, staff training, consumer debriefing, and regular feedback. Forster and colleagues26 focused their training on increasing awareness of factors that lead to agitation and violence, teaching less restrictive interventions, and the teaching of safe reactions to patient violence. Borckardt and colleagues27 implemented an engagement model that includes trauma-informed care training, changes in rules and language, patient involvement in treatment planning, and changes to the physical characteristics of the therapeutic environment. Project BETA believes that the culture that promotes the use of restraint and seclusion can be changed. This will require implementing programs with the above features, plus specific training in verbal, de-escalation techniques.

GUIDELINES FOR THE USE OF SECLUSION AND RESTRAINT

When seclusion or restraint is necessary, the least restrictive intervention should be chosen. The Figure shows a recommended algorithm. Unless the patient is actively violent, verbal de-escalation should be tried first. The clinician should offer medication and try to involve the patient in decisions about medication. If the patient is an immediate danger to others, restraint is indicated. If the patient is not a danger to others, seclusion should be considered. However, if the patient would be a danger to himself while in seclusion, restraint is appropriate. If the restrained patient will engage in a reasonable dialog, verbal de-escalation efforts should continue, including getting the patient’s input on medication. Either way, medication should be administered to calm a patient who has been placed in restraints. If restraint is not indicated and the patient is willing to sit in a quiet, unlocked room, then an unlocked seclusion room should be used. If not, then forced seclusion is indicated. For some patients, seclusion with decreased stimulation is adequate for them to regain control. For others, medication should be considered, and ongoing efforts at verbal de-escalation may be beneficial. All patients in restraint or seclusion should be monitored to assess response to medication and to prevent complications from these interventions. Treatment should be directed toward minimizing time in forced seclusion or restraint. Once the patient has regained control, a more thorough evaluation can be done, followed by further treatment planning and determining disposition.

In summary, approaches for reducing seclusion and restraint episodes that may be applied to ED/PES settings include change in organization culture where restraint is viewed as a treatment failure, implementing an administrative quality management review process aimed at improving outcomes in manging aggrerssive behavior, regular staff feedback, early identification and intervention using de-escalation techniques, and the use of protocols or aggressive mangement algorithms to guide clinical interventions.

In addition, it is important, as well as legally mandated, that CMS guidelines be followed and incorporated into the program’s policies and procedures. All clinical staff in an ED or PES must have training on an annual basis at a minimum on verbal de-esclation techniques and the prevention and management of aggressive behavior. All staff members, including physicians, should be familiar with the types of restraints used in their programs and how to appropriately apply, monitor, and assess potential bodily injury that might result from application of the restraints. Use of video cameras in the clinical areas that are used by clinical staff to monitor the clinical environment can also be used in an instructive manner to review the restraint or seclusion episode to see if other, less forecful, interventions could have been tried. Where possible, time set aside to debrief staff and patients on the seclusion and restraint episode can provide valuable learning opportunites as well as a way to verbalize and process feelings surrounding the event.

CONCLUSION

While it may not be possible to eliminate incidents of seclusion and restraint in the PES or ED setting, more can be done to reduce the current rate of these incidents. It is important to keep in mind that often a patient’s first entry into the mental health system can be through the doors of an emergency department. Patients may be at their lowest point of functioning, whereby their perceptions are altered, their sense of reality is grossly impaired, and they are being forced into treatment. It is in this atmosphere that emergency clinicians must make the most of a very unpleasant experience for the patient by endeavoring to make the experience as therapeutic as possible, with the goal of getting that patient into ongoing psychiatric treatment to minimize the likelihood of another decompensation and emergency setting encounter. “The new psychiatric emergency department is a place to start treatment and not one whose primary purpose is restraint, triage or referral.”28

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Leslie Zun, MD

Submission history: Submitted July 29, 2011; Revision received September 7, 2011; Accepted September 16, 2011

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

DOI: 10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6867

Address for Correspondence: Daryl K. Knox, MD

Mental Health and Mental Retardation Authority of Harris County, Comprehensive Psychiatry Emergency Program, 1502 Taub Loop, Houston, TX, 77030

E-mail: daryl.knox@mhmraharris.org

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding, sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Holloman GH, Jr, Zeller SL. Overview of Project BETA: best practices in evaluation and treatment of agitation. West J Emerg Med. 2011;13:1–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

2. Department of Health and Human Services. Condition of participation: patient’s rights. Federal Register 482.13. 2006. pp. 71426–71428.

3. Haimowitz S, Urff J, Huckshorn KA. Restraint and seclusion—a risk management guide. 2011. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Web site. Available at:http://www.nasmhpd.org/general_files/publications/ntac_pubs/R-S RISK MGMT 10-10-06.pdf. Accessed July 6.

4. Fisher WA. Restraint and seclusion: a review of the literature. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1584–1591. [PubMed]

5. Mohr WK, Petti TA, Mohr BD. Adverse effects associated with physical restraint. Can J Psychiatry.2003;48:330–337. [PubMed]

6. Frueh BC, Knapp RG, Cusack KJ, et al. Patients’ reports of traumatic or harmful experiences within the psychiatric setting. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1123–1133. [PubMed]

7. Duhart DT. Publication No. NCJ 190076. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice Programs; 2001. Violence in the Workplace, 1993–99.

8. Gates DM, Ross CS, McQueen L. Violence against emergency department workers. J Emerg Med.2006;31:331–337. [PubMed]

9. Lam LT. Aggression exposure and mental health among nurses. Adv Ment Health. 2002;1:89–100.

10. Grange JT, Corbett SW. Violence against emergency medical services personnel. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2002;6:186–190. [PubMed]

11. Cheney PR, Gossett L, Fullerton-Gleason L, et al. Relationship of restraint use, patient injury, and assaults on EMS personnel. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2006;10:207–212. [PubMed]

12. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Summary report: a national call to action: eliminating the use of seclusion and restraint. SAMHSA Web site. Available at:http://www.samhsa.gov/seclusion/sr_report_may08.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2011.

13. McCue RE, Urcuyo L, Lilu Y, et al. Reducing restraint use in a public psychiatric inpatient service.J Behav Health Serv Res. 2004;31:217–224. [PubMed]

14. Khadivi AN, Patel RC, Atkinson AR, et al. Association between seclusion and restraint and patient-related violence. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:1311–1312. [PubMed]

15. Smith GM, Davis RH, Bixler EO, et al. Pennsylvania State Hospital system’s seclusion and restraint reduction program. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1115–1122. [PubMed]

16. Donat DC. An analysis of successful efforts to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint at a public psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1119–1123. [PubMed]

17. Sharfstein SS. Commentary: reducing restraint and seclusion: a view from the trenches. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:197. [PubMed]

18. Sullivan AM, Bezmen J, Barron CT, et al. Reducing restraints: alternatives to restraints on an inpatient psychiatric service—utilizing safe and effective methods to evaluate and treat the violent patient. Psychiatr Q. 2005;76:51–65. [PubMed]

19. Lewis M, Taylor K, Parks J. Crisis prevention management: a program to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint in an inpatient mental health setting. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2009;30:159–164. [PubMed]

20. Jonikas JA, Cook JA, Rosen C, et al. A program to reduce use of physical restraint in psychiatric inpatient facilities. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:818–820. [PubMed]

21. Zun L. A prospective study of the complication rate of use of patient restraint in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2003;24:119–124. [PubMed]

22. Busch AB. Special section on seclusion and restraint: introduction to the special section.Psychiatric Serv. 2005;56:1104.

23. Zun LS, Downey L. The use of seclusion in emergency medicine. Gen Hosp Psychiatry.2005;27:365–371. [PubMed]

24. Downey LV, Zun LS, Gonzales SJ. Frequency of alternative to restraints and seclusion and uses of agitation reduction techniques in the emergency department. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:470–474. [PubMed]

25. Ashcraft L, Anthony W. Eliminating seclusion and restraint in recovery-oriented crisis services.Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:1198–1202. [PubMed]

26. Forster PL, Cavness C, Phelps MA. Staff training decreases use of seclusion and restraint in an acute psychiatric hospital. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1999;13:269–271. [PubMed]

27. Borckardt JJ, Madan A, Grubaugh AL, et al. Systematic investigation of initiatives to reduce seclusion and restraint in a state psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:477–483. [PubMed]

28. Berlin J. Psychiatric emergency department: where treatment should begin. Psychiatric News Web site. Available at: http://pn.psychiatryonline.org/content/46/14/12.1.full. Accessed September 4, 2011.