| Author | Affiliation |

| Kristin Berona, MD | Los Angeles County + University of Southern California Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Angeles, California |

| Kevin Hardiman, DO | Los Angeles County + University of Southern California Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Angeles, California |

| Thomas Mailhot, MD | Los Angeles County + University of Southern California Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Angeles, California |

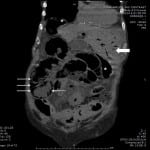

A 76-year-old female with a history of Parkinson’s, dementia, and hypertension presented to the emergency department with non-bilious, non-bloody vomiting and abdominal pain for 2 days. Her exam was significant for borderline hypotension without tachycardia, abdominal distension and a palpable ventral hernia. An emergency physician performed ultrasound showed free intraperitoneal air and gas in the liver (Video). A computed tomography showed pneumoperitoneum, pneumatosis intestinalis, and hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) (Figure). At laparotomy, she was found to have a sigmoid colon perforation from adenocarcinoma, ischemic small bowel, and a colovesicular fistula. Post-operatively her clinical status worsened, and she was transitioned to comfort care and expired on hospital day 2.

HPVG was first reported in infants with necrotizing enterocolitis.1 In adults, it is most commonly associated with mesenteric ischemia and pneumatosis intestinalis, accounting for 43% of HPGV cases2 and an associated mortality of 75%.2-3 It has been reported with other diseases such as diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, obstructive pyelonephritis, pancreatitis, cholangitis, uterine gangrene, and severe shock.4 HPVG is attributed to either bacterial gas production in bowel entering mesenteric circulation4 or intraluminal air entering capillaries from impaired mucosal barrier or increased intraluminal pressure.5 HPVG spreads to the periphery of the liver whereas pneumobilia collects centrally, in the direction of bile flow. Treatment is always aimed at the underlying etiology of HPVG.

Figure. Computed tomography without contrast of the abdomen and pelvis showing free air (asterisks), pneumatosis intestinalis (thin arrows), and hepatic portal venous gas (large arrow).

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Sean O. Henderson, MD

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Kristin Berona, MD, LAC+USC Medical Center, 1200 N. State St. Room 1011, Los Angeles, CA Email: kberona@gmail.com.

Submission history: Submitted July 23, 2014; Revision received September 2, 2014; Accepted September 23, 2014

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

Video. Ultrasound videos in epigastrium and right upper quadrant showing pneumoperitoneum and hepatic portal venous gas.

REFERENCES

- Wolfe JN, WA Evans. Gas in the portal veins of the liver in infants; a roentgenographic demonstration with postmortem anatomical correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1955;74(3):486-488. [PubMed]

- Kinoshita H, Shinozaki M, Tanimura H, et al. Clinical features and management of hepatic portal venous gas: four case reports and cumulative review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1410-1414. [PubMed]

- Liebman PR, Patten MT, Manny J, et al. Hepatic-portal venous gas in adults: etiology, pathophysiology and clinical significance. Ann Surg. 1978;187:281-287. [PubMed]

- Abboud B, El Hachem J, Yazbeck T, et al. Hepatic portal venous gas: physiopathology, etiology, prognosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(29):3585-90. [PubMed]

- Nelson AL, Millington TM, Sahani D, et al. Hepatic portal venous gas: the ABC’s of management. Arch Surg. 2009;144(6):575-581. [PubMed]