| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Miriam W. Boeri, PhD | Kennesaw State University, Department of Sociology, Kennesaw, GA |

| Benjamin D. Tyndall, BA | Kennesaw State University, Department of Sociology, Kennesaw, GA |

| Denise R. Woodall, BS | Kennesaw State University, Department of Sociology, Kennesaw, GA |

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

This paper aims to identify the needed healthcare and social services barriers for women living in suburban communities who are using or have used methamphetamine. Drug users are vulnerable to injury, violence and transmission of infectious diseases, and having access to healthcare has been shown to positively influence prevention and intervention among this population. Yet little is known regarding the social context of suburban drug users, their risks behaviors, and their access to healthcare.

Methods:

The data collection involved participant observation in the field, face-to-face interviews and focus groups. Audio-recorded in-depth life histories, drug use histories, and resource needs were collected from 31 suburban women who were former or current users of methamphetamine. The majority was drawn from marginalized communities and highly vulnerable to risk for injury and violence. We provided these women with healthcare and social service information and conducted follow-up interviews to identify barriers to these services.

Results:

Barriers included (1) restrictions imposed by the services and (2) limitations inherent in the women’s social, economic, or legal situations. We found that the barriers increased the women’s risk for further injury, violence and transmission of infectious diseases. Women who could not access needed healthcare and social resources typically used street drugs that were accessible and affordable to self-medicate their untreated emotional and physical pain.

Conclusion:

Our findings add to the literature on how healthcare and social services are related to injury prevention. Social service providers in the suburbs were often indifferent to the needs of drug-using women. For these women, health services were accessed primarily at emergency departments (ED). To break the cycle of continued drug use, violence and injury, we suggest that ED staff be trained to perform substance abuse assessments and provide immediate referral to detoxification and treatment facilities. Policy change is needed for EDs to provide the care and linkages to treatment that can prevent future injuries and the spread of infectious diseases.

INTRODUCTION

Methamphetamine (MA) is a stimulant that affects the central nervous system and releases dopamine neurotransmitters to the brain while simultaneously inhibiting their uptake. This produces a pleasurable experience along with increased activity and decreased appetite. The effects of MA “may include increased blood pressure, hyperthermia, stroke, cardiac arrhythmia, stomach cramps and muscle tremor; acute negative psychological side effects include anxiety, insomnia, aggression, paranoia and hallucinations,” while MA withdrawal may produce “fatigue, anxiety, irritability, depression, inability to concentrate and even suicidality.”1 MA use can damage nerve terminals and cause body temperature to become dangerously elevated.

MA users, compared to users of other drugs, have more serious health problems, risk behaviors and exposure to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.2–10 A review of the literature on MA use and injury found that injuries were primarily associated with driving and violence, as well as related to MA production.11

Studies show that drug-using females, especially those who inject drugs, are a vulnerable population for transmission of infectious diseases.2,5 Female MA users also show more indicators of depression than male users and are more likely to report they use MA for self-medication and weight-loss.12While female MA users are vulnerable to the same risk factors as men, social and economic context has a greater impact on women MA users than on men, and women are motivated to use MA for social and emotional reasons rather than sexual stimulation. 13–14 Moreover, injuries related to physical violence were reported more among female than male MA users.15

Research shows that injection risk behaviors among drug users are socially learned and influenced by the social context of drug use.16–23 Yet we have little understanding of the social context of suburban drug users, their risk behaviors, and their awareness of drug-related diseases. Even less is known regarding socially marginalized suburban women who use drugs and lack access to needed healthcare. Due to the stigma related to drug use, the risk for injury is intensified for women who use drugs and are afraid of admitting to their drug use, often intimidated by potential legal repercussions.

The aim of this paper is to identify the barriers to needed healthcare and social services for suburban women who use or have used MA. We used a sample of women interviewed in a research study on MA users in the suburbs funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Our broad long-term goal is to better understand how to provide services for women marginalized by drug use and poverty in order to prevent further injury, violence and transmission of diseases.

METHODS

Based on a two-year study on MA use in the suburbs, we found that women were at greater risk for injury and diseases than were the men in our study. This prompted a second study to further examine the social context, reasons for drug use, risk behaviors and access to needed healthcare and social services among a sample of female MA users living in the suburbs. The study field included the 12 counties that surround a large metropolitan area in the southeastern United States. Only those counties recognized as suburban areas of the city were included in our field recruitment.

Recruitment and Screening

Recruitment began with researchers spending time in the field and becoming acquainted with various drug-using networks. We used a combination of targeted, snowball, and theoretical sampling methods to recruit non-institutionalized participants.24,25 We first used a screening process to ensure that participants passed the eligibility criteria: being 18-years or older and having used MA in the suburbs. Screening consisted of asking questions that were not related to the criteria (e.g., do you have children, are you employed) so that criteria eligibility could not be guessed. The researcher’s university Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. Data collection started in February 2010, and the last participant was enrolled in March 2011.

Data Collection

We used a longitudinal design consisting of three interviews: a first in-depth interview, drug history and risk behavior inventory; a second follow-up interview; and a third follow-up interview in conjunction with a focus group. Participants chose to join a focus group or conduct the third follow-up interview alone. Interviews were audio-recorded and conducted in a private location agreed upon by the interviewer and participant, including the participant’s home, private library rooms, a private university research office and the interviewer’s car. The principal investigator and trained, certified research assistants conducted the interviews face-to-face. No identifying material was collected. Signed consent was obtained before collecting information. The recordings were transcribed verbatim. The qualitative data included field notes, interviewer notes, and transcripts of interviews and focus groups. All data were protected by a certificate of confidentiality granted by NIDA, which also protected the researchers from court subpoena. This certificate aided in helping to gain the trust of the participants, as was our willingness to help women access the resources they needed. Our involvement with accessing resources merits further explanation.

During the first interviews, participants were provided a list with the numbers and addresses of the healthcare and social services in their counties in response to their expressed needs. These included medical and dental services, psychiatric counseling, family counseling, legal services, employment services, screening for (HIV), hepatitis C (HCV) and sexually transmitted diseases, detoxification and drug treatment, food and housing services. Initially, we drew from a pamphlet of resources that was freely provided by local government and non-profit social services, and we added those we found through our own searches on the internet. At the follow-up interviews we inquired about the women’s success at accessing and using services from the individualized resource list we gave them. During the focus group sessions, we again discussed each resource we provided, if it had been contacted, and how successful the women were in having their needs met by these resources. After a few follow-up interviews, and upon learning that the majority of resources the women had contacted either did not respond or responded negatively to requests for help, we began to call from the lists ourselves to confirm what the women told us. The typical response to our inquiries was to be referred to another service. Based on these referrals, our resource list increased.

Sample

Thirty-one women were interviewed, and of these over half completed all three interviews. Ages ranged from 19 to 50-years-old. Twelve were active users of MA, defined as having used MA at least once in the 30 days prior to the last interview. Seventeen reported to having injected drugs, and four knew of their positive HCV status. Twenty-four women were identified as part of a marginalized sub-population, defined as having little or no employment, no permanent housing, no dependable transportation, and inconsistent access to a telephone number. While all women asked for and were given resource lists for their specific needs, we primarily worked with the marginalized and most vulnerable women to try to find needed resources. This subgroup represents the majority of the women described in this paper.

RESULTS

All transcripts and notes were coded to better examine the barriers the women experienced. The commonly reported barriers were combined under one of two categories: restrictions and limitations. Restrictions are barriers implemented by the social service or their regulatory agency, such as mandatory fees and waiting lists. Limitations are related to the women’s own limited resources to access services, such as lack of phone or transportation.

Restrictions to Services

The most common restrictions experienced by our participants were identification requirements, mandatory fees, waiting lists, service use caps and having a criminal or drug use history, which virtually “blacklisted” the women from accessing resources. Below we give examples of these restrictions based on our field experience with the population and quotes from the participants. We learned that many participants already knew of these restrictions, and, therefore, never attempted to access resources that might have been available to them. Others who had already been turned away previously attempted to access them again in the naïve hope that our referral provided some source of social capital.

Government Approved Identification

Most services require some form of identification (ID)—typically a government-issued ID, such as a driver’s license or military card. Our efforts to help our participants obtain an ID led to a “Catch-22” dilemma when we discovered they needed an official birth certificate to be issued an ID, but they could not obtain their birth certificate unless they provided proof of identification. For example, one homeless participant looking for shelter had lost all but one proof of ID (an old social security card). Her official driver’s license had been stolen, and she could not be re-issued one until she provided two acceptable proofs of ID, one being a birth certificate. The process of obtaining her birth certificate continued to present challenges, as she needed an immediate form of payment over the phone, a fax machine to send her proof of ID, and an address to receive the certificate, all of which were unavailable to her. Without her ID, we were not able to help her find any shelter or even obtain food from the community food pantry.

Another young woman left all her belongings and paperwork when she abruptly left the trailer where she had lived with an abusive boyfriend. When we tried to help her obtain these items, her ex-boyfriend said he had thrown them away. Without her ID, she was prohibited from accessing needed treatment. We soon learned that what one woman said was true for all: “If you don’t have two forms of ID, together, you don’t have nothing.”

Mandatory Minimum Fees

The primary resource needed by the women that was most inaccessible was healthcare, including medical, psychological and dental services. Clinics that charged sliding scale fees revealed a minimum payment that often presented a restriction for many homeless and almost homeless women. Those services that did not charge a fee had other restrictive payment requirements, such as proof of Medicaid, which presented a seemingly insurmountable challenge of paperwork for those who might qualify. Only one woman in our sample who attempted to qualify for Medicaid actually obtained it, after a nearly two-year wait. When we met her she had been unemployed for years, a victim of domestic violence, and indicated what appeared to be mental health problems. Blinded in one eye by a recent accident, she was helped with the copious paperwork by the women in her community.

Women without Medicaid or insurance typically could not afford even the minimum payment. When we told one woman about a program that required a minimum of only $12, she replied:

“Well, if I could afford it then I would do that. I would, but I can’t afford that 12 dollars a day. I can’t. There’s no way. I mean, I do good to come up with a couple dollars a day to put in my car so I can get somewhere…but it’s hard.”

Perpetual Waiting Lists

Long waiting lists were a significant barrier for housing, medical and dental services, emergency financial assistance, and inpatient substance abuse treatment. To our surprise, even domestic violence shelters had waiting lists. Most of our participants who attempted to access resources for which they qualified reported various responses from the service providers that essentially meant there was a waiting list. For example, one woman told us, “They wasn’t giving out any assistance until the first of the month when they got funds in.” Others who asked to get on a list were told that the waiting list was closed.

Service Use Caps

Another surprising finding was that the services needed by the most poor had restrictions on the number of times they could be used. These included emergency food services and homeless shelters. One homeless woman described her situation saying, “Once you leave the shelter, you can’t go back for six months, so that wasn’t an option. I had nowhere to go; I was headed for the woods.” We heard similar stories outside the only homeless shelter in one suburban county as the homeless were turned away for reaching their maximum nights of use without finding employment.

In another instance, we found that if the homeless women did not use a service for several weeks, their files would be closed. After a patient’s files were closed, their name was placed at the end of a long waiting list when they tried to access services again. This was the case at a suburban health center providing a narrow range of physical and mental health services where some women became unable to access needed psychotropic medications. The state of these women during this time left them more vulnerable to numerous health and safety risks.

Blacklisted: Criminal Records and Drug and Alcohol Screens

Criminal convictions, particularly drug convictions, affected our participants’ ability to receive food, shelter, and other basic resources they needed when employment was almost impossible to obtain due to their record. In other cases, the women would have been eligible to stay at the only homeless shelter in the area but were restricted due to drug and alcohol testing. Rather than any desire to be “high,” we learned that their reasons for continuing drug use were due to their insecure situations, mental health issues, or physical and emotional pain that was left untreated. In fact, many women wanted help for their addiction to alcohol or drugs. One woman who was expelled from a shelter told us she would like to have drug treatment, and she tried to stop on her own, but it was difficult in her current homeless status: “I’m having a hard time struggling with drugs. I do need treatment, but I can’t get in [and] I don’t have a way to comply with the shelter rules.”

The use of drugs and alcohol to ease their troubled state of existence is well known, and we found women are especially susceptible to using alcohol or drugs when in a relationship with a user. For example, one woman, who had been drug-free for over three months, was allowed entry to a homeless shelter and permitted to stay after she found part-time employment at a nearby business. She was doing well until she accepted a beer from a homeless man she befriended and was denied entry to the shelter after failing a breathalyzer test. The next time we saw her; this 50-year-old woman was prostituting on a busy highway and staying at a low-rate motel where she took her clients.

Limitations to Service Use

In addition to the barriers that restricted access to services, the women often did not use services for which they qualified, due to social and economic limitations endemic among marginalized populations. The most common limitations experienced by our participants were no transportation, lack of communication technology, and fear of unwanted governmental intrusion.

Lack of Public Transportation

Transportation limitations were ubiquitous for our suburban population. If there was any public transportation in the suburban communities, it was very limited in terms of geographic coverage and frequency of service. Additional transportation services offered in some counties had other limitations, such as short hours of operation and appointment requirements.

Some women asked neighbors with cars for help; however, when they relied on the charity of others, they were often at the mercy of these people’s busy schedules, and frequently left without a ride due to unforeseen circumstances. Since the women did not have reliable transportation, they missed multiple appointments and either stopped trying access services or, at times, were told they could not schedule another appointment since they had missed so many. Suburban women who knew of free or affordable services in the city were cut off from these more comprehensive and accommodating urban service centers for lack of transportation.

We discovered that among most of the marginalized communities we studied, men owned cars more than did women. The working-class men typically needed a car since they relied on it for many kinds of part-time work that required their own equipment (i.e. small construction jobs, scrap metal collection, landscaping). The farther away from shopping and service areas the women lived, the more dependent they were on men with cars. We found that this meant some women remained dependent on abusive partners with access to transportation. One participant described her geographically isolated situation when her abusive partner left her, “I can’t get anywhere. I can’t do anything. I’m stuck.”

Communication Problems: “Leave a Message”

As mentioned previously, even those females who were fortunate enough to have a residence were often faced with the dilemma of not having a working phone number for callbacks from social services. We found that most of the phone numbers listed for social services were answered with a voice mail recording asking the caller to leave their name and a number to call back, which these women usually could not provide. Moreover, even when calls were answered by a live staff person, it was typically a volunteer or intern who wanted nothing but a name and phone number to give to a supervisor at an undisclosed later date. As one participant attempting to find a job through her county’s department of labor explained, “Well, I mean, I gave someone’s phone number, but, you know, that’s not their problem. When you look for a job, you got to have a phone.” Another woman corroborated when she tried to access financial services, “They wanted a telephone number to call you back, and you get a recording…but they acted like they would help me if I had a number for them to call back.” Eventually, our researchers helping the women left our own phone number, but we were rarely called back. While we became frustrated, our participants became disheartened. “Just forget it,” we heard too often when we encouraged them to try again.

Fear of Government Intrusion

Fear of governmental intrusion was also a serious concern for the women who were using or had used illegal drugs and were seeking help. Homeless shelters often drug test mothers with children, putting them at risk for unwanted intervention by the Department of Family and Child Services. Others had already experienced losing their children to social service care and were afraid to even attempt help from any government source.

Most of the women did not want contact with law enforcement, which limited their access to services. For example, one woman called us to ask to go to an emergency department (ED). She did not have transportation, and in the past she was billed for the ambulance. The EDs we contacted told us that if a patient needed to get to the hospital without an ambulance, they should call the police. Typically, current or former drug users who have had negative encounters with the police in the past were not willing to do this since it calls attention to their drug-using situation. Domestic violence shelters also tended to have this same requirement. To keep their locations confidential, they preferred that clients arrive in a police car. Our female participants were repeatedly unwilling to call the police for help. As one said, “How do I know I can trust them? No, no way, I’m not doing that.”

Consequences of Barriers to Services

Injuries

The lack of health services often resulted in injuries associated with continued drug use. The women recounted their experiences of untreated injuries to themselves or their families due to a lack of ongoing medical care. During a focus group, one woman explained:

“My son broke his arm and I didn’t have insurance so they just put a temporary cast on him and that’s all they would do. They will say, “Follow up with so-and-so [family doctor] in two days.” When you go to that doctor then you got to write a check or they’re just not going to take you.”

Another participant in the focus group agreed as she held up a broken finger, describing a similar scenario: “I was supposed to follow up with a surgeon but I didn’t have the money, it’s still broken and it still hurts!”

In some instances, use of the drug itself was involved in the injuries sustained by the women. The interviewer was summing up this woman’s case:

“You had an accident on methamphetamine so that’s why you can’t see well. Well, you were on Xanax and methamphetamine at the time. And you fell and the knife went into your eye…[Participant: To the back of my skull.]”

Remaining in these vulnerable circumstances without resources left women at risk of serious injury that often went improperly treated.

Violence

One chronic social disease that often resulted in injury was domestic violence. Nearly 80% of the suburban women in our sample experienced domestic violence, and many lived with abusive partners in their homes or had former violent partners living in their communities. This left them at risk for unexpected violence. One woman admitted that her missing teeth were due to an estranged husband’s anger, and he still showed up unannounced at the home where she was now living. Without the social capital or economic means to obtain a legal divorce, there was little for her to do but wait until he hit her before she could call the police. She had learned, as another woman corroborated, that without physical abuse, the police in her area would not do anything. Two women in our sample reported having been taken to the police station and jailed when they were defending themselves against abusive husbands and the police believed they were the perpetrators of the violence instead.

Those women with no one to take them in reported assaults by strangers. Barriers to homeless shelters, described above, left the women exposed to violent attacks on the street, such as the homeless woman who recounted a violent episode that left a visible scar:

“I was cut in ’07 in my face and my hand by a [man] on the street. Just for no reason, he just walked up, gang-related shit, you know. And I’m too old to be out there fighting off these people on the streets… And he thought well, gee, there goes a—let me go cut her up. Nobody’s going to miss her. I’ve even had police officers tell me that. “How many man hours, how many tax dollars do you think we’re going to spend looking in the woods for your butt? If you’re stinking in the woods, we’ll find you one day.”

Infectious Diseases

Seventeen women in our sample were injectors, and as such they were at risk for more health problems in the absence of needed services. Focus group discussions revealed how the scarcity of services that address drug use in suburban areas increases this population’s risk of injury and infectious disease. The unavailability of new syringes heightens their risk of injury, as does their lack of proper sterilization knowledge and equipment. One participant said, “A lot of people don’t have access to water or boiling water. Yeah, they use dirty creek water. I’ve seen somebody use lake water, and I’ve seen people use spit.” While some women knew that syringes were more accessible in the city, few of our participants had transportation or ventured that far if they did. Most expressed apprehension of buying syringes in a pharmacy for fear of being labeled a drug user. The women who knew how to obtain syringes often got them from friends who were diabetic or who knew a diabetic.

Public health issues, such as the spread of infectious diseases, emerged as a major concern. Only half of the women in our sample knew their HCV status, and of these, four women reported to have been diagnosed with HCV. While many women had not been tested for years, a few learned of their status while in jail. Participants with HCV reported multiple barriers to treatment, and untreated injectors were at higher risk for injury while they remained untreated. These women were unable to obtain laboratory tests to diagnose the stage of their HCV or receive consistent medical attention. For example, a female injector, 21-years-old, recently learned that she had HCV when she was in jail for possession and distribution of MA. When asked if she knew how she got it, she replied, “Hepatitis C…is very prevalent in [suburban town]. I can name at least five friends that have it.” At the time of her last interview, she was receiving no healthcare or further treatment due to lack of resources, including no insurance and no transportation. Moreover, she was refused care at two public clinics because she did not live in the same county and did not have the proper paperwork. Subsequent contact with her revealed that she was continuing to inject MA in high-risk social settings.

Treatment for Drug Abuse

Gender played a part in lacking access to detoxification, stabilization units and/or drug treatment facilities. In the area of our study, many more inpatient facilities exist for men than for women. For women with children, the premium for bed space is especially high. In an attempt to find a detoxification and treatment residence for one woman, 45 calls were made to various treatment facilities by the participant and our research staff. This count, drawn from field notes, did not include call transfers, returned calls, or unreported calls. This homeless woman, like most of those we interviewed, was a polydrug user taking whatever was available to ease her suffering. Withdrawing from physical addiction to methadone and Xanax, she went to an ED and was released after 12 hours as “medically stable” while still homeless, psychologically drug addicted, and without medication for her high blood pressure. When we called the ED to understand why she was released without detoxification and drug treatment for opioids, the hospital staff responded, “We can’t give our beds to drug addicts.” Her continued drug use left her vulnerable to greater injuries as she combined drugs that were available to her from unreliable sources. Similar to many of the most marginalized and vulnerable women in our study, we lost contact with her.

Detoxification is not available to MA users for the purpose of MA withdrawal. Other than evidence of a threat of harm to self or to others, free public-funded facilities required the presence of benzodiazepines or alcohol in the bloodstream for the patient to be considered for long-term detoxification and treatment. Some women learned that if they said they were suicidal, they might be accepted into an ED and possibly a detoxification facility. In one case, a woman who had recently relapsed knew from previous experiences at an ED in another county that she had to have alcohol in her blood and be suicidal to be admitted. She presented with these symptoms and received long-term help. Today this woman lives in a safe aftercare home and has employment.

DISCUSSION

Our findings show two alarming facts regarding access to needed services for the most marginalized women living in suburban areas: (1) legitimate services have numerous restrictions and limitations that act as barriers to obtaining needed healthcare, shelter, and other resources; (2) these barriers frequently leave these women in a vulnerable state and subject to further injury, violence or infection.

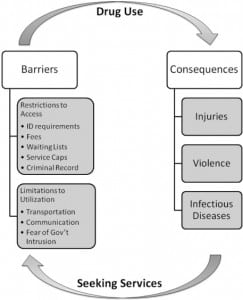

The stories of these women revealed a cycle of drug use followed by barriers encountered while attempting to access needed social services, followed by more drug use to ease their now increasing pain and suffering. Figure 1 depicts this cycle of barriers to needed services and the drug use that are both causes and consequences of each other in a recursive process.

The cycle does not necessarily begin with drug use. MA was frequently cited by the women as a way of forgetting emotional scars, such as childhood traumas like rape and molestation. Others used it to cope with domestic violence and emotional abuse. The consequences of using MA–chiefly injury, violence, and disease–subsequently led the women to seek health and social services.

Restrictions such as ID requirements and long waiting lists were met with apathy by marginalized service consumers, who tended to surrender hope of accessing needed resources based on past experiences. Inability to access emergency resources, such as shelter in the winter, psychotropic medications, or follow-up care to ED visits, left the women open to greater risks and vulnerable to injuries.

Limitations to services were exacerbated by the lack of public transportation in suburban areas. Reliance on transportation for the most basic needs, such as food, work, and healthcare, left many of the women in vulnerable situations with abusive partners or voluntarily exposing themselves to harm from former boyfriends or strangers in exchange for transportation.

For the majority of our socially isolated participants, EDs were their only source of healthcare. Others have found, similarly, that EDs are the primary source of healthcare for chronic drug users and other vulnerable populations.26, 27 A study by Larson et al28 found that a high rate of ED use was associated with barriers to regular care similar to those we found, including lack of insurance, inability to pay for services, difficulty with transportation, and substance abuse issues. Healthcare use and risk prevention awareness has been shown to help prevent HIV and other infectious disease transmission, but a lack of resources and continuity of care are barriers to healthcare and treatment.29–33

The ED is an important point of contact between marginalized drug users and health and social service providers, often during times of greatest need. Kellerman34 identified ED physicians and staff as critical sources for injury control. Yet our study findings show that marginalized female MA users living in the suburbs not only experienced multiple barriers to healthcare use, but they also lacked continual care or injury prevention after ED visits. McCoy35 suggests that this may be due in part to the fact that primary and emergency providers of healthcare may lack sufficient knowledge and training when dealing with substance users. The same study shows that simple drug user awareness training can both improve attitudes and knowledge about users and their needs as well as encourage implementation of drug use screening and assessment protocols. We echo others’ suggestions for care providers to identify health and social needs when marginalized users present at EDs and to connect them with social workers and resources beyond their stay in the ED.28, 35, 36

LIMITATIONS

The major limitation of this study is that it cannot be generalized beyond the research sample. However, as a primarily qualitative study, it does not require a probability sample. The goal is to gain a better understanding of injury risk behaviors and access to healthcare and social services among a suburban sample of female MA users. A convenience sample is sufficient to achieve this goal.37–9 Despite its limitations, the findings from this qualitative study contribute to the literature an in-depth and detailed understanding of injury risks faced by marginalized women living in the suburbs.

CONCLUSION

We know that drug use is a significant factor in violence and injury, particularly among women, and MA-using females are more likely to be exposed to injury and violence than their male counterparts.15 Our findings show that healthcare and social services are related to injury and violence prevention, but in the suburbs these services often are overburdened, under-funded and intimidating to drug-using women. Lack of services or access to services leaves women and their children vulnerable to the risk of injuries. We found that many of these women receive their only healthcare while incarcerated or at EDs. We know that preventative healthcare at public funded clinics is a more feasible solution, and ultimately is less costly to the taxpayer than emergency care.31, 34

More can be done within the public health field to prevent injury among drug-using populations. Prevention and intervention initiatives can be placed in community health clinics with specialized staff trained in drug-related injuries and diseases. Women and others who come to the ED for drug-related injuries or ask for drug treatment should be taken to the appropriate treatment facility, either detoxification units or residential treatment. Those who test positive for HCV should be offered continued care.40 Compared to public spending for those who repeatedly use ED for injuries, and who are at greater risk for contracting infectious diseases, providing treatment appears to be a more economically feasible solution than to discharge drug addicts seeking treatment when they are “medically stabilized.” If this is the current policy, efforts should be made to have policy changed.

Finally, attention needs to be focused on addressing the needs and limitations that are unique to vulnerable populations in the suburbs. While urban areas have the greatest numbers of residents needing social and healthcare resources, they also have more services aimed at the poor. However, suburban rates of poverty and associated drug use and crime are increasing.41 Suburban ED staff should be trained in substance abuse assessment, HIV and HCV prevention, screening and continued care, and to provide drug users who present at EDs access to treatment on demand. While these require short-term funding, they are less costly to municipal and state healthcare budgets than the long-term expenses incurred by treating the multiple injuries and diseases resulting from untreated drug addiction and associated violence and transmission of infectious diseases.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Monica H. Swahn, PhD, MPH

Submission History: Submitted January 15, 2011; Revision received: March 14, 2011; Accepted March 18, 2011

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem.

Address for Correspondence: Miriam W. Boeri, PhD

Kennesaw State University, 1000 Chastain Road, Kennesaw, GA 30144

Email: mboeri@kennesaw.edu

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

The project described was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Award numbers 1R15DA021164; 2R15DA021164. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health. We would like to acknowledge co-investigator, Annette Bairan, who helped with final proofreading and the women who shared their intimate stories and health concerns with us.

REFERENCES

1. Barr AM, Panenka WJ, MacEwan GW, et al. The need for speed: an update on methamphetamine addiction. J Psychiat Neurosci. 2006;31:301–13.

2. Bourgois P, Prince B, Moss A. The everyday violence of hepatitis C among young women who inject drugs in San Francisco. Hum Organ. 2004;63:253–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

3. Compton WM, Thomas YF, Conway KP, et al. Developments in the epidemiology of drug use and drug use disorders. Am J Psychiat. 2005;162:1494–1502. [PubMed]

4. Jones K, Urbina A. Crystal methamphetamine, its analogues and HIV infection: medical and psychiatric aspects of a new epidemic. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:890–94. [PubMed]

5. Lorvick J, Martinez A, Gee L, et al. Sexual and injection risk among women who inject methamphetamine in San Francisco. J Urban Health. 2006;83:497–505. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

6. Ostrow D. The role of drugs in the sexual lives of men who have sex with men: continuing barriers to researching the question. AIDS Behav. 2000;4:205–19.

7. Rawson RA, Gonzales R, Obert JL, et al. Methamphetamine use among treatment-seeking adolescents in Southern California: participant characteristics and treatment response. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;29:67–74. [PubMed]

8. Rodriguez N, Katz C, Webb VJ, et al. Examining the impact of individual, community and market factors on methamphetamine use: a tale of two cities. J Drug Issues. 2005;35:665–93.

9. Semple S, Zians J, Grant I, et al. Impulsivity and methamphetamine use. J Subst Abuse Treat.2005;29:85–93. [PubMed]

10. Worth H, Rawstone P. Crystallizing the HIV epidemic: methamphetamine, unsafe sex and gay diseases of the will. Arch Sex Behav. 2005;34:483–86. [PubMed]

11. Sheridan J, Bennett S, Coggan C, et al. Injury associated with methamphetamine use: a review of the literature. Harm Reduct J. 2006;3:14–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

12. Hser Y, Evans E, Huang YC. Treatment outcomes among women and men methamphetamine abusers in California. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28:77–85. [PubMed]

13. Maher L. Sexed Work: Gender, Race, and Resistance in a Brooklyn Drug Market. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1997.

14. Gorman EM, Clark CW, Nelson KR, et al. A community social work study of methamphetamine use among women: implications for social work practice, education and research. J Soc Work Pract Addict. 2003;3:41–62.

15. Cohen JB, Dickow A, Homer K, et al. Abuse and violence history of men and women in treatment for methamphetamine dependence. Am J Addiction. 2003;12:377–85.

16. Berkman LF, Glass T. Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, editors. Social Epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 137–73.

17. Blankenship KM, Koester S. Criminal law, policing policy, and HIV risk in female street sex workers and injection drug users. J Law Med Ethics. 2002;30:548–49. [PubMed]

18. Chitwood D, Griffin DK, Comerford M, et al. Risk factors for HIV-1 seroconversion among injection drug users: a case-control study. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:1538–42. [PMC free article][PubMed]

19. Curtis R, Friedman SR, Neaigus A. Street level drug markets: network structure and HIV risk. Soc Networks. 1995;17:229–49.

20. Fitzpatrick K, LaGory M. Unhealthy Places: The Ecology of Risk in the Urban Landscape. New York, NY: Routledge; 2000.

21. Neaigus A, Friedman SR, Curtis R, et al. The relevance of drug injectors’ social and risk networks for understanding and preventing HIV infections. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:67–78. [PubMed]

22. Poundstone KES, Strathdee A, Celantano D. The social epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:22–35. [PubMed]

23. Schensul JJ, Radda K, Weeks M, et al. Ethnicity, social networks and HIV risks in older drug users. Adv Med Soc. 2002;8:167–97.

24. Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998.

25. Watters J, Biernacki P. Targeted sampling: options for the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl.1989;36:416–30.

26. McCoy CB, Metsch LR, Chitwood DD, et al. Drug use and barriers to use of health care services.Subst Use Misuse. 2001;36:789–806. [PubMed]

27. McGeary KA, French MT. Illicit drug use and emergency room utilization. Health Serv Res.2000;35:153–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

28. Larson MJ, Saitz R, Horton NJ, et al. Emergency department and hospital utilization among alcohol and drug-dependent detoxification patients without primary medical care. Am J Drug Alcohol Ab. 2006;32:435–52.

29. Des Jarlais DC, McKnight C, Goldblatt C, et al. Doing harm reduction better: syringe exchange in the United States. Addiction. 2009;104:1441–6. [PubMed]

30. Needle RH, Coyle S. Community Based Outreach Risk Reduction Strategy to Prevent Risk Behaviors in Out-of-Treatment Injection Drug Users. Rockville, MD: NIDA/NIH Consensus Development Document; 1997.

31. Anglin MD, Hser Y. Criminal justice and the drug-abusing offender: policy issues of coerced treatment. Behav Sci Law. 1991;9:243–67. [PubMed]

32. Carrière GL. Linking women to health and wellness: street outreach takes a population health approach. Int J Drug Pol. 2008;19:205–10.

33. Robles RR, Matos TD, Colon HM, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(S5):S392–403. [PubMed]

34. Kellermann AL. The base of the pyramid. West J Emerg Med. 2010;11:233–4. [PMC free article][PubMed]

35. McCoy HV, Messiah SE, Zhao W. Improving access to primary health care for chronic drug users: an innovative systemic intervention for providers. J Behav Health Ser R. 2002;29:445–57.

36. Silverman M, LaPerriere K, Haukoos JS. Rapid HIV testing in urban emergency department: using social workers to affect risk behaviors and overcome barriers. Health Soc Work. 2009;34:305–8. [PubMed]

37. Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000.

38. Lambert EY, Ashery RS, Needle RH. Qualitative Methods in Drug Abuse and HIV Research. NIH Publication No. Washington DC: National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1995. pp. 95–4025.

39. Varjas K, Talley J, Meyers J, et al. High school students’ perceptions of motivations for cyberbullying: an exploratory study. West J Emerg Med. 2010;11:269–73. [PMC free article][PubMed]

40. Sylvestre D. Approaching treatment for hepatitis C infection in substance users. Clin Infect Dis.2006;41:S79–82. [PubMed]

41. Raphael S, Stoll MA. Job sprawl and the suburbanization of poverty. The Metropolitan Policy Program, Brookings. 2010.