| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Thomas E. Terndrup, MD | Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania |

| James M. Leaming, MD | Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania |

| R. Jerry Adams, PhD | Evaluation and Development Institute, Denver, Colorado |

| Spencer Adoff, MD | Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania |

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

Surge capacity for optimization of access to hospital beds is a limiting factor in response to catastrophic events. Medical facilities, communication tools, manpower, and resource reserves exist to respond to these events. However, these factors may not be optimally functioning to generate an effective and efficient surge response. The objective was to improve the function of these factors.

Methods:

Regional healthcare facilities and supporting local emergency response agencies developed a coalition (the Healthcare Facilities Partnership of South Central Pennsylvania; HCFP-SCPA) to increase regional surge capacity and emergency preparedness for healthcare facilities. The coalition focused on 6 objectives: (1) increase awareness of capabilities and assets, (2) develop and pilot test advanced planning and exercising of plans in the region, (3) augment written medical mutual aid agreements, (4) develop and strengthen partnership relationships, (5) ensure National Incident Management System compliance, and (6) develop and test a plan for effective utilization of volunteer healthcare professionals.

Results:

In comparison to baseline measurements, the coalition improved existing areas covered under all 6 objectives documented during a 24-month evaluation period. Enhanced communications between the hospital coalition, and real-time exercises, were used to provide evidence of improved preparedness for putative mass casualty incidents.

Conclusion:

The HCFP-SCPA successfully increased preparedness and surge capacity through a partnership of regional healthcare facilities and emergency response agencies.

INTRODUCTION

Hospital emergency departments (ED) are crowded and often at overcapacity, yet most local and regional community surge plans call for transporting all seriously ill and injured patients to regional EDs for immediate stabilization and definitive care.1Catastrophic events have recently tested responses of these communities and have illustrated the need for further improvement.2 Such events include the Haitian earthquake in 2010, the novel influenza H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic of 2009, and Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Furthermore, national-level exercises such as “Dark Winter” and the Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program (HSEEP) have repeatedly exposed areas where the need for improvement in response is clear.3–7 For political leaders, health officials, hospital leaders, and emergency management officials, upholding public confidence in their respective institutions before, during, and after a catastrophic event is crucial. This can be done by increasing preparedness for public health emergencies, largely those that require the ability to treat a large influx of patients (surge capacity).

The purpose of this article is to describe an approach to improve surge capacity, in this case for hospital and ED treatment areas. The timely availability of these treatment areas is crucial for all seriously ill and injured patients, and for the public’s health, when a mass casualty incident (MCI) occurs. The region in which these activities took place is demographically consistent with much of the United States, insofar as it includes a locale containing multiple hospitals of various sizes and capabilities; emergency medical service (EMS) and emergency management agencies (EMA) as response agencies; limited public health services; and both sparsely and densely populated areas, including small towns, rural areas, and modest urban and suburban populations.

We used the resources enabled by a federal grant purposed to examine the benefit of developing a partnership of healthcare facilities as part of The Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP) of the Department of Health and Human Services.8 The HPP was created “to improve the state of medical and public health.”9 While part of the HPP’s mission is to increase preparedness in hospitals and emergency response systems for natural and terrorist disasters, there are scant data on its effectiveness or on how implementation can be achieved.

The Healthcare Facilities Partnership of South Central Pennsylvania

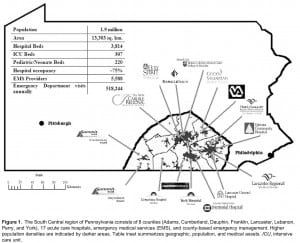

The Healthcare Facilities Partnership of South Central Pennsylvania (HCFP-SCPA; Partnership) consists of the following counties of Pennsylvania: Adams, Cumberland, Dauphin, Franklin, Lancaster, Lebanon, Perry, and York. The region is composed of both rural and micro and metro urban areas, and has a hospital capacity and capability that ordinarily serves the needs of these communities (Figure 1). Within this region, a total of 17 acute care hospitals became members of the Partnership, which was supported by a federal grant from September 1, 2007, to August 8, 2009, inclusive of 2 no-cost extensions to the initial award.

The South Central region of Pennsylvania consists of 8 counties (Adams, Cumberland, Dauphin, Franklin, Lancaster, Lebanon, Perry, and York), 17 acute care hospitals, emergency medical services (EMS), and county-based emergency management. Higher population densities are indicated by darker areas. Table inset summarizes geographic, population, and medical assets. ICU, intensive care unit.

METHODS

Background

The Partnership leveraged the structure of the South Central Pennsylvania Regional Counter-Terrorism Task Force (SCTF), EMAs, and the Emergency Health System Federation (EHSF, regional EMS agency) as important and established entities with an identical geography to that of the HCFP-SCPA with which to formulate planning efforts. The SCTF’s mission is to deliver a comprehensive and sustainable regional “all-hazards” emergency preparedness program that addresses planning, prevention, response, and recovery for events in South Central Pennsylvania that exceed local capabilities. The SCTF, supported primarily by grants from the Department of Homeland Security, is organized into approximately 10 functional groups and committees. It consists of representatives from 16 hospitals, the Office of Public Health Preparedness, 8 county EMAs, and other critical entities required for public health and safety for a population of about 2 million people.

The EHSF is the regional EMS council for the South Central Pennsylvania region. It consists of more than 200 quick response services, basic life support services, and advanced life support services. It provides information and education for the community and EMS personnel. The EHSF also works to improve preparedness and recruitment and provides regional resources that can be deployed in the event of a required response.

Also in place before the development of the Partnership was the federal Emergency System for Advance Registration of Volunteer Health Professionals Program (ESAR-VHP). The ESAR-VHP (a product of HHS in response to volunteer-related complications on September 11, 2001) is a registration program of healthcare professionals who will potentially volunteer their efforts in the event of a mass casualty event. ESAR-VHP expedites the volunteer’s verification of identity, licenses, credentials, and accreditations. In the state of Pennsylvania, ESAR-VHP is known as The State Emergency Registry of Volunteers in Pennsylvania (SERV-PA).

Structure

The project responded to 6 objectives: (1) enhance situational awareness of capabilities and assets in the South Central Region of Pennsylvania; (2) develop and pilot test advanced planning and exercising of plans in the region; (3) augment written medical mutual aid agreements (MMAA) between healthcare facilities in the region, with special emphasis on hospitals; (4) develop and strengthen partnership relationships through joint planning, frequent communication, simulation, and evaluation of preparedness; (5) ensure National Incident Management System (NIMS) compliance; and (6) develop and test a plan for effective utilization of the ESAR-VHP.

After the grant was awarded, personnel from the SCTF, the largest 7 EMS companies, and 11 hospitals within the region were provided the opportunity to participate in specific roles including planning, collaboration, development, and training activities. The project contracted with additional key partners to provide both technical assistance and outcomes measurements.

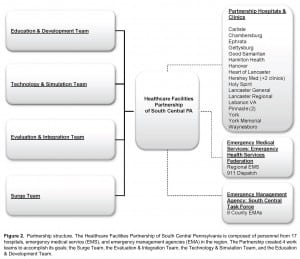

Four primary teams were formed within the Partnership to establish modes, mechanisms, procedures, and evaluation techniques to fulfill the goals created for the grant. These teams were (1) education and development, (2) technology and simulation, (3) evaluation and integration, and (4) surge enhancement. Each team consisted of 6 to 10 members including 1 acting team leader and 1 coleader. Teams met regularly to discuss current developments and to further the goals as set forth by the HCFP as a whole. The response to this model (Figure 2) for completing the work was received favorably by members of the Partnership and this proved an efficient means of task management for its overall goals.

Partnership structure. The Healthcare Facilities Partnership of South Central Pennsylvania is composed of personnel from 17 hospitals, emergency medical service (EMS), and emergency management agencies (EMA) in the region. The Partnership created 4 work teams to accomplish its goals: the Surge Team, the Evaluation & Integration Team, the Technology & Simulation Team, and the Education & Development Team.

Through early Partnership discussions, a consensus was reached that surge capacity would be defined as “the number of adequately staffed beds that can be provided in addition to the normal demand within 2 hours of an incident,” which includes accounting for both inpatient and ED treatment beds. The Partnership focused around this unifying, central concept.

Specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-framed (SMART) objectives were created from the 6 grant objectives. These SMART objectives centered on multiple projects and assessments. Each of the 59 SMART objectives created by the Partnership included a description of how to measure or document the objective, and the person or persons who took the lead to implement each, and provided a deadline for completion.

Obtaining the Six Goals

Inclusive and frequent communication was evaluated as essential for the Partnership to act as 1 cohesive unit. Two specific tools were implemented to enhance contact during meetings and to immediately collaborate on data and information: a desktop-sharing tool and a toll-free number. The desktop–sharing program (Webinar, Web-based seminar) was fully interactive, which allowed all attendees to present, respond to, and discuss information in real time. The Webinar program was complemented by a toll-free number. Attendees of Webinar meetings were able to communicate verbally during sessions by calling into a phone conference. Using the Webinar with phone, meetings could be held and “attended” by all parties, regardless of their location within the 8 counties (approximately 13,303 km2). This significantly reduced travel costs and allowed partners to complete their other regular duties with less interruption to their everyday workflow.

The Partnership conducted regularly scheduled discussions between regional healthcare facilities on shared needs to enhance surge capacity. Emphasis was based on frequent development, reduced dependency on face-to-face meetings, and growth of mutual understanding of hospital-based procedures.

To better communicate situational awareness, emergency alert systems were improved. These systems were the Facility Resource Emergency Database (FRED) system, an 800-MHz radio system, and the Health Alert Network (HAN) system. FRED is an Internet-based system that alerts facilities in the event of a crisis or situation that may warrant a coordinated response. It provides information about the emergency and enables facilities to report about available resources. The 800-MHz radio is a system implemented by the Pennsylvania Department of Health as a means to alert and communicate in the event of failure of primary communication methods. HAN is a national system developed by the Center for Disease Control that alerts facilities of any health threat using Web- and satellite-based technologies, and then links organizations critical for preparedness and response to said events.

These alerts were tested, improved, and practiced by using the Comprehensive Hazard and Vulnerability Analysis (HVA), the HSEEP, the pandemic influenza exercise (PanSurge07) assessment, and the PanFlu assessment. The Partnership also established triggers for activating those systems and created an “ideal communication” flow chart for the South Central Pennsylvania region.

A Web-based portal (http://hcfp-scpa.org) was created that had both a public and private (secured) component. On the secured access portion of the portal, members of the Partnership are able to share information about the surge capability of their particular hospital. Hospitals reported bed capacity in key areas such as the ED, intensive care unit, pediatric intensive care unit, and medical/surgical floors. The portal also kept a central repository for information regarding availability of equipment, similar to that of the National Hospital Available Beds for Emergencies and Disasters System developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. On the public portion of the Web site, the Partnership created a way to communicate with the region’s communities about preparedness efforts and emergency situations.

To gather effectiveness and outcomes data, brief Web-based surveys and polls, as well as larger hospital and regional exercises, were performed to quantify various outcomes and clarify roles and responsibilities. To develop a library of low-cost repeatable training exercises, 3 computer simulations were created: a pandemic influenza outbreak (gradual and persistent surge simulation), mass casualty blast incident (sudden surge simulation), and a hospital evacuation scenario (“reverse” surge simulation). These flat-screen, computer-based simulations incorporated the HVA, PanSurge07, and PanFlu assessment results for at-risk medical populations.

Regional hospital MMAAs were examined and updated, where possible. All participating healthcare facilities reviewed, enhanced, and agreed upon updated MMAAs that now included the availability of volunteers (SERV-PA). Updated MMAAs were also signed between EMS agencies.

A SERV-PA administrator at each of the HCFP-SCPA hospital facilities was designated and trained. The administrators were given responsibility and oversight for volunteer alerts and organization of volunteers during an actual event. The HCFP-SCPA carried out a week-long recruiting event to encourage volunteers to register at each regional facility. The SERV-PA program was advertised on the Partnership Web site and at several of the hospitals in the region to further encourage volunteer enrollment. Following recruitment, the SERV-PA system was tested to determine how many new volunteers were generated.

The NIMS training requirements were simplified to become more appropriate for the hospital-based participants, and training was made more accessible to all Partnership hospitals, with an online certification process. A new NIMS compliance template was created and distributed on the Partnership Web site.

After several months of information gathering and discussion, the Partnership evaluation and integration team identified 6 gaps in the overall progress and focused on remediating these specific gaps. The gaps were identified as requirement for (1) increased capacity through staffing and alternative care sites, (2) improved efficiency through preparedness standardization, (3) decompression of hospitals by working with alternative care sites, (4) development of command and control and NIMS compliance, (5) development of improved transportation planning, and (6) enhanced surge capacity through broader participation.

RESULTS

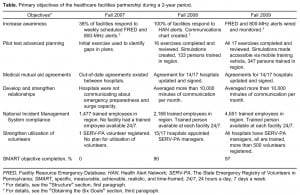

Outcomes of the Partnership were targeted to be realistic, measurable, time-conscientious, and repeatable so as to be available for implementation by other hospital expanses looking to develop partnerships. Progress was evaluated by the completion of the 59 SMART objectives (Table) and tested through implementation of 17 brief regional exercises.

Preparedness

The HCFP-SCPA produced various resources to strengthen emergency preparedness. The 3 computer-based simulations were created and used throughout the region as an education tool. Along with this, the Partnership launched a Web-based portal with a public and secure access to facilitate communication between partners and with the public. A regional “ideal communication flow chart” (Figure 3) was created and trigger points for surge response were identified and agreed upon to further strengthen communication.

![Figure 3 Communication flow chart. In the eventuality of an event, 911 is notified, emergency medical service is dispatched, and emergency management agencies (EMA) are contacted (when a mass casualty incident [MCI] has/may have occurred). Incident scene operations may require emergency operations center (EOC) support for MCIs of significant magnitude. The EMAs are then responsible for producing a Pennsylvania Emergency Incident Reporting System (PEIRS) report. Information on the PEIRS report is passed through the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency (PEMA), to the Pennsylvania Department of Health (DOH), to the Emergency Health Services Federation (EHSF), and then to the hospitals who will be receiving the patients. To achieve faster situational awareness for hospitals, the 911 service now directly contacts local hospitals in the event of a significant occurrence for which surge is possible. These local hospitals then contact regional hospitals capable of creating a Facility Resource Emergency Database (FRED) alert that notifies all hospitals in the region.](https://westjem.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/6853-f3-300x216.jpg)

Communication flow chart. In the eventuality of an event, 911 is notified, emergency medical service is dispatched, and emergency management agencies (EMA) are contacted (when a mass casualty incident [MCI] has/may have occurred). Incident scene operations may require emergency operations center (EOC) support for MCIs of significant magnitude. The EMAs are then responsible for producing a Pennsylvania Emergency Incident Reporting System (PEIRS) report. Information on the PEIRS report is passed through the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency (PEMA), to the Pennsylvania Department of Health (DOH), to the Emergency Health Services Federation (EHSF), and then to the hospitals who will be receiving the patients. To achieve faster situational awareness for hospitals, the 911 service now directly contacts local hospitals in the event of a significant occurrence for which surge is possible. These local hospitals then contact regional hospitals capable of creating a Facility Resource Emergency Database (FRED) alert that notifies all hospitals in the region.

Preparedness was also strengthened through assessment. Seventeen regional data gathering and assessment exercises were conducted during the time period of the grant. After each was performed, the partnership evaluated and reviewed the results to identify limitations in the region as a whole and within each Partnership facility.

Relationships were built and strengthened by the HCFP-SCPA. The frequent communication between partners improved relationships informally. Formally, MMAAs were signed and updated between facilities. Outside the partners, alternative care sites were identified and officially recognized.

Training, policies, and procedures for working with volunteers during a surge were developed or adopted. Fifteen of 17 hospitals appointed SERV-PA managers and all were sufficiently trained by the end of the granting period. More than 500 SERV-PA volunteers had been added within the region since the start of the project. This compares favorably with the 600 volunteers that were available statewide at the beginning of the Partnership.

After implementation of the grant projects, NIMS compliance increased in the independent study (IS) 100 by 1,395; in the IS 200 by 1,439; in the IS 700 by 220; and in the IS 800 by 120, in the region. This should lead to a greater ability for hospitals to meaningfully participate in disaster response.

During the initial HAN alert system exercise, 76% of the hospitals confirmed receipt of HAN alerts and 45% of the personnel within the hospital received the alert. After review and improvements were made, a second exercise was completed. In the repeated exercise, HAN alert system No. 2, 100% of the hospitals confirmed receipt of the alert and 47% of the personal within the hosptials confirmed receipt.

At baseline, an average of 38% of healthcare facilities responded to scheduled weekly alerts on the FRED and 800-MHz systems. In all, 50% of hospitals were responding to the 800-MHz alert system, and 62% of hospitals were using the FRED alert system (31% used both systems). Some facilities did not respond to the FRED or the 800-MHz system. At the conclusion of the grant, all hospitals had the 800-MHz radio, wired and monitored continually, and had practiced receiving the FRED alert.

Surge Capacity

Surge capacity was analyzed by a contemporaneous phone survey of cooperating hospitals of the region. This was performed by using the Health Alert Network and Web portal communications as an alerting activity, followed by a teleconference documenting capacity for surge at 0700 and 1500 hours at each facility. At baseline in 2007, it was determined that total regional surge capacity for critical adult patients was 10 or less and for critical pediatric patients, 2 or less. Regionally, this had not been available previously on a contemporaneous basis. After exercises, self-reported capacity for the responding hospitals showed an average regional hospital surge capacity of 342 beds over the baseline of 3,192 beds (a 10.7% regional increase with surge capacity). After these surge capacity exercises, we were able to demonstrate the following increases in hospital beds: 25% increase in adult floor beds, 37% increase in critical care beds, 27% increase in ED beds, and a total regional increase of 24%. However, no increase in pediatric capacity could be created regionally without changing the Department of Health regulations on designated use of adult and pediatric beds. In subsequent practice sessions, verifiable alternative care expansion and personnel availability were shown to produce more than 3,600 low-acuity, staffed evaluation and treatment rooms for surge capacity enhancement within the region. These exercises asked hospital organizations to identify usable, staffed clinical areas that could be directed to care for patients needing education, immunization, and low-acuity visits but not requiring services only available within the affiliated hospital. These sessions assumed that the ESAR-VHP was used to augment staffing of available beds (ie, movement of providers assured between hospital organizations), that memorandum of understandings between hospital organizations resulted in enhanced coordination between overloaded and other hospital organizations, and that staffed beds for low-acuity patients could provide a load of 4 patients per treatment room per hour.

DISCUSSION

During initial review, it was clear that many improvements to the emergency response system were needed in the region. Many systems that were expected to respond to MCI and other surge emergencies, such as NIMS, MMAAs, and ESAR-VHP, were in existence but not functioning optimally.

During the granting period, we observed and demonstrated the importance of testing emergency response, not only as a single healthcare entity but also as a regional healthcare system. In particular, it is important for key jurisdictions within a healthcare region to practice communication in order for a flow of information to go from the initial dispatch to all of the key jurisdictions that need to respond, including hospitals. It was clear to the Partnership that without significant practice and troubleshooting, the path of communication did not move rapidly from the initial dispatch to all of the event catchment hospitals.

We highlighted the need for effective practice exercises and simulations. Practice made it possible to troubleshoot the complex decision making effectively. Simulation training with the regional facilities is a priority and is crucial to sustain regional disaster preparedness. The computer-based simulation added additional interactive and qualitative data and measurements that exceeded previous real-time exercises, such as tabletops.

LIMITATIONS

This project had several important limitations. Although the South Central Pennsylvania region has many communities, hospital facilities, and demographics that are similar to other regions, no 2 points across the country are the same. Each region has individual requirements, restrictions, and resources, which may differ from ours. However, we believe that much of our technique can be replicated elsewhere.

The members of the partnership were asked to disclose information to the HCFP-SCPA, and much of the data were reliant on this self-reporting. Furthermore, we rely on the partners to uphold preparedness and surge quality after the end of the grant period. Although we believe that our partners are dedicated to emergency preparedness and increasing surge capacity, the incident of fraudulence is possible. Similarly, while we feel that improvement in hospital personnel participation is a result of participation in, and actions of, the HCFP-SCPA, the possibility exists that subjects improve or modify an aspect of their behavior that is being experimentally measured in response to the fact that they are being studied.

CONCLUSION

The Partnership successfully increased preparedness and surge capacity through a coalition of regional healthcare facilities and emergency response agencies. At baseline, the healthcare facilities in our region of Pennsylvania had the ability to accommodate 10 critically ill patients. At the conclusion of the study, the Partnership has practiced a regional response to a large surge event and has found an increase in capacity that exceeds 100 patients.

Table.

Primary objectives of the healthcare facilities partnership during a 2-year period.

Footnotes

We would like to thank the members of the Healthcare Facilities Partnership of South Central Pennsylvania and their representatives: Hanover Hospital (Joshua Hale), Gettysburg Hospital (Ron Sterchak), Chambersburg Hospital (Vickie Negley), Waynesboro Hospital (Dan Farner), The New Carlisle Regional Medical Center (Georgeann Laughman), Holy Spirit Hospital (Jason Brown), Pinnacle Health (Christie Muza), Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center (Scott Freeden), Good Samaritan Health System (Kim Crosson), Heart of Lancaster Regional Medical Center (Scott Marks), Ephrata Community Hospital (Gloria Jean Maser Fluck), Lancaster Regional Medical Center (Walter Roth), Lancaster General Hospital (Jeffery Manning), York Memorial Hospital (Lisa Ziegler), and York Hospital (Kevin Arthur). We would also like to thank Osteopathic Hospital, The Lebanon Veterans Affairs Medical Center, The University Physicians Group-Fishburn, the University Physicians Group-Middletown, and The South Central Pennsylvania Regional Counter-Terrorism Task Force. We would also like to thank Nancy Flint, Carla Perry, Shannon Harrington, and Lee Groff for their help. We would like to thank Christopher Hatzi and Dennis Damore of Crisis Simulations International, LLC (CSI). These activities were supported in part by a grant from the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Preparedness and Emergency Operations, Division of National Healthcare Preparedness Programs, grant No. HFPEP070002-01-01.

Supervising Section Editor: Christopher Kang, MD

Submission history: Submitted July 13, 2011 ; Revision received August 29, 2011 ; Accepted October 3, 2011

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.orgfucfuciem_westjem

DOl: 10.5811fwestjem.2011.10.6853

Address for Correspondence: Thomas E. Terndrup, MD, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, H043, 500 University Dr, PO Box 850, Hershey, PA 17033-0850

E-mail: tterndrup@hmc.psu.edu

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Barbisch DF, Koenig KL. Understanding surge capacity: essential elements. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:1098–1102. [PubMed]

2. Schafermeyer RW, Asplin BR. Hospital and emergency department crowding in the United States. Emer Med (Fremantle) 2003;15:22–27. [PubMed]

3. Steinman M, Lottenberg C, Pavao OF, et al. Emergency response to the Haitian earthquake: as bad as it gets. Injury [published online ahead of print July 30, 2010][PubMed]

4. Brevard SB, Weintraub SL, Aiken JB, et al. Analysis of disaster response plans and the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina: lessons learned from a level I trauma center. J Trauma.2008;65:1126–1132. [PubMed]

5. Hota S, Fried E, Burry L, et al. Preparing your intensive care unit for the second wave of H1N1 and future surges. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:e110–e119. [PubMed]

6. O’Toole T, Mair M, Inglesby TV. Shining light on “Dark Winter” Clin Infect Dis.2002;34:972–983. [PubMed]

7. US Department of Homeland Security. Homeland security exercise and evaluation program, volume I: HSEEP overview and exercise program management. Available at:https://hseep.dhs.gov/support/VolumeI.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2011.

8. US Department of Health and Human Services. HHS awards health care facilities partnership program grants. Available at:http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2007pres/09/pr20070927c.html. Accessed June 22, 2011.

9. US Department of Health and Human Services Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response. Report on the hospital preparedness program. Available at:http://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/hpp/Documents/hpp-healthcare-coalitions.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2011.