| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Ryan M Knight, MD | San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, Fort Sam Houston, Texas |

| Peter J Cuenca, MD | San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, Fort Sam Houston, Texas |

ABSTRACT

In this report, we discuss a case of a 14-month-old male presenting in the emergency department with refusal to bear weight on his left leg. Plain radiographic studies revealed no evidence of effusion, fracture, or dislocation. Laboratory studies were significant for an elevated white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. Further studies included unremarkable ultrasound of the left hip and normal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of both hips. An incidental finding on MRI was a left inguinal mass concerning an incarcerated hernia. Ultrasound of this mass demonstrated a left undescended testis within the inguinal canal and possible incarcerated paratesticular inguinal hernia. The final pathologic diagnosis of a torsed gangrenous left testicle within the inguinal canal was confirmed during surgery.

CASE REPORT

A 14-month-old male presented to our emergency department (ED) refusing to bear weight on his left leg since waking in the morning. His parents reported a 4-day history of elevated temperatures with a maximum temperature of 100.4°F. Per his parents’ report, he normally walks independently. His parents also reported decreased oral intake, increased fussiness the day of presentation, and no bowel movement for 3 days prior to presentation. The parents denied vomiting, inconsolable crying, loose stools, cough, congestion, recent illness, or sick contacts prior to his presentation in the ED. His past medical history was significant for congenital hip dysplasia, treated only with nightly bracing, and bilateral undescended testes. The family recently moved to the area and had not established care with an urologist regarding orchiopexy. The child received only 1 round of immunizations due to parental preoccupation with his congenital hip dysplasia, undescended testes, and the family’s recent move. He had no known drug allergies, did not take any medications, and had no family history of disease.

Physical exam revealed blood pressure 93/49 mmHg, heart rate of 153 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 28 breaths per minute, temperature of 100.4°F, oxygen saturation 96% on room air, and a weight of 10 kg. The child was fussy but consolable sitting on his mother’s lap. When placed in a standing position, the patient held his left hip in flexion, abduction, and external rotation, refusing to allow his foot to touch. He was able to hold all his weight on his right foot. Skin exam revealed no evidence of exanthema, erythema, warmth, induration, or fluctuance. Full passive range of motion of the left hip was intact and caused no additional distress to the child from his baseline crying. His abdominal exam revealed a soft, nontender, nondistended abdomen without masses, guarding, or rebound. His genital exam revealed a circumcised male with undescended testes bilaterally. No inguinal masses were seen or palpated. The remainder of his physical examination was unremarkable.

Radiographs of his left hip, femur, and knee demonstrated no fracture, effusion, or other abnormal process. Laboratory studies were remarkable for a leukocytosis of 16.7 and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) at 103 mm per hour and 4.7 mg/L respectively. A single blood culture was drawn. An ultrasound of his left hip was performed and demonstrated no joint effusion.

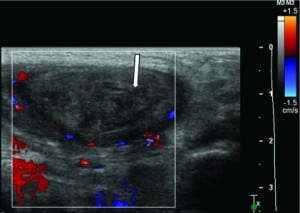

Orthopedics was consulted, and the patient was admitted to pediatrics for an inpatient magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the left hip to evaluate for septic joint prior to proceeding to the operating room for joint aspiration. This MRI showed normal appearing hips but did reveal a left inguinal mass concerning an incarcerated hernia (Figures 1 and 2). An ultrasound of this mass was performed and demonstrated an undescended testicle within the inguinal canal as well as an associated paratesticular inguinal hernia with possible incarceration (Figures 3 and 4). Surgical exploration revealed a gangrenous, torsed left testicle within the inguinal canal. The patient underwent a successful left orchiectomy and inguinal canal reconstruction and was scheduled to return to the operating room in 4 weeks for right-sided orchiopexy. The patient’s recovery was uneventful, and he was discharged from the hospital in 3 days.

DISCUSSION

Refusing to bear weight in a child is a concerning complaint and has a broad differential.1 Infectious causes include septic arthritis, transient synovitis, osteomyelitis, diskitis, and cellulitis. Neoplastic causes include bony tumors, such as Ewing’s sarcoma, osteochondroma, and osteosarcoma, as well as neuroblastoma, leukemia, and lymphoma. Trauma and nonaccidental trauma must always be considered in this pediatric complaint. Abdominal pathology for this complaint includes appendicitis, psoas abscess, and genitourinary disorders, such as testicular or ovarian torsion (Table).

Routine laboratory testing is neither specific nor sensitive regarding the workup of patients with a limp or refusing to bear weight. Tests should be ordered based on the history and physical exam findings to help establish the diagnosis. Laboratory tests can be helpful when malignancy, infection, or inflammatory arthritis is suspected.2 These tests should include a complete blood count, ESR, CRP, and a blood culture and lyme testing if geographically appropriate.3

Radiographic studies should begin with standard radiography, which can reveal fractures, dislocations, large effusions, and are noninvasive, relatively inexpensive, and easily obtained. An oblique view of the tibia and fibula increases the sensitivity to diagnose a toddler’s fracture. Further studies should be ordered based on the history and physical. Ultrasonography can help detect small effusions, soft tissues masses, and is also noninvasive. Studies such as computer axial tomography (CT), bone scan, and MRI may also be indicated. CT can quickly diagnose abdominal pathology or bony abnormalities. MRI is useful for spinal pathology, soft tissue masses, tumors of the bone, and intra-articular pathology.4

Testicular torsion is classically described as having a bimodal distribution with peaks being within the first year of life and early in puberty.5 Although this bimodal distribution is the most common presentation, torsion can occur at any age and must be considered in any male with acute scrotal or abdominal pain.6 Although a rare event overall, among patients with undescended testes, torsion is not uncommon and is the primary indication for surgical correction once the patient is deemed safe for general anesthesia. A recent 20-year retrospective review found only 11 cases with most cases in the perinatal period.7 Another study found a torsion rate of 3.8% of patients going to the operating room with an undescended testis.8 Andersen and Wille-Jorgensen9 present a 3.6% rate of undescended testicular torsion in a 5-year retrospective study of patients with suspected torsion. For poorly understood reasons, torsion more commonly occurs in the left testis.10 The presentations of these cases have been associated with groin pain, a palpable mass, or inconsolable crying. None of these cases are reported in the 1- to 3-year-old age range; most are in children under 1 year of age, making this a unique case in medical literature.

In the undescended testicle, torsion classically occurs in the perinatal period and is considered unlikely after the first year of life. However, the highest incidence of testicular torsion occurs in the young adult population.11 Most testes are unsalvageable at the time of diagnosis due to the difficulty of the diagnosis in this age range.6,7 Due to the consequences of a missed diagnosis, clinicians must have a high index of suspicion and always keep testicular torsion part of their differential diagnosis with any child refusing to bear weight. Doppler ultrasound has emerged as the test of choice for diagnosis of testicular torsion; however, a high false negative rate remains. Sensitivity of 87.9% and specificity of 93.3% for Doppler ultrasound for testicular torsion is reported, but this is much lower in the case of the undescended testis.12,13 Current literature recommends orchiopexy by the age of 2. The rate of spontaneous descent declines significantly after 3 months of age, and the risks of surgery and general anesthesia decrease after 1 year.14

The previous cases reported in the literature of infants or toddlers with undescended testicular torsion had symptoms that led to a diagnosis of nonspecific abdominal pain leading to the final diagnosis. These symptoms include inconsolable crying, intolerable feeding, or restlessness. This case lacks those features as the child continued to feed and was fussy but consolable. He did not have a palpable inguinal mass or any apparent distress with abdominal or genitourinary exam.

The child who refuses to bear weight or use a joint should be considered to have a serious condition until proven otherwise and necessitates a through workup until the source is revealed.15 Testicular torsion must be included in the differential of any child with an empty scrotum and concerning symptoms. Salvage rates are estimated at 90% to 100% if detorsion occurs within 6 hours of onset of symptoms, but decline to 20% after 12 hours and 0% to 10% if delayed longer than 24 hours.16However, severe damage is reported to occur within 4 hours of onset of symptoms.17 Early urologic consultation is critical, even prior to definitive diagnosis if suspicion is high enough.

CONCLUSION

The primary issues in the case of a pediatric patient with an undescended testicular torsion are both delay in presentation and delay in diagnosis, leading to a necrotic testicle. These children usually present late with nonspecific symptoms that lead to a broad differential that must be quickly narrowed if the child is to have a salvageable testicle. Patients undergoing orchiectomy can have issues with fertility later in life secondary to a decreased sperm count. This case demonstrates a nonspecific history and physical examination in a child outside the classic age range for testicular torsion. Emergency physicians must use available diagnostic tools to quickly narrow the differential and appropriately dispose the child to raise the chance of a salvageable testicle.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Judith R. Klein, MD

Submission history: Submitted November 2, 2010; Revision received December 31, 2010; Accepted March 30, 2011

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

DOI: 10.5811/westjem.2011.3.2126

Address for Correspondence: Ryan M. Knight, MD

San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, 3851 Roger Brooke Dr, Fort Sam Houston, TX 78234

E-mail: rmk103@hotmail.com

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Leet AI, Skaggs DL. Evaluation of the acutely limping child. Am Fam Physician. 2000;;61:1011–1018. [PubMed]

2. Kocher MS, Mandiga R, Murphy JM, et al. A clinical practice guideline for treatment of septic arthritis in children: efficacy in improving process of care and effect on outcome of septic arthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;;85-A:994–999. [PubMed]

3. McCollough M, Sharieff GQ. Abdominal pain in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;;53:107–137. [PubMed]

4. De Boeck H, Vorlat P. Limping in childhood. Acta Orthop Belg. 2003;;69:301–310. [PubMed]

5. Cuckow PM, Frank JD. Torsion of the testis. BJU Int. 2000;;86:349–353. [PubMed]

6. Saad S, Duckett O. Urologic and gynecologic problems in children. In: Tintinalli JE, Ruiz E, Krome RL, editors. Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;; 2004. pp. 900–905.

7. Zilberman D, Inbar Y, Heyman Z, et al. Torsion of the cryptorchid testis—can it be salvaged? J Urol. 2006;;175:2287–2289. [PubMed]

8. Ibrahim AH, Al-Malki TA, Ghali AM, et al. Undescended testes: Do we need to fix them earlier? Ann Pediatr Surg. 2005;;1:21–25.

9. Andersen L, Wille-Jorgensen PA. Torsion of the testis. A 5-year material. Scand J Urol Nephrol.1990;;24:91–93. [PubMed]

10. Ringdahl E, Teague L. Testicular torsion. Am Fam Physician. 2006;;74:1739–1743. [PubMed]

11. Mowad JJ, Konvolinka CW. Torsion of undescended testis. Urology. 1978;;12:567–568.[PubMed]

12. Liu CC, Huang SP, Chou YH, et al. Clinical presentation of acute scrotum in young males.Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2007;;23:281–286. [PubMed]

13. Bentley DF, Ricchiuti DJ, Nasrallah PF, et al. Spermatic cord torsion with preserved testis perfusion: initial anatomical observations. J Urol. 2004;;172:2373–2376. [PubMed]

14. Barthold JS, Gonzalez R. The epidemiology of congenital cryptorchidism, testicular ascent and orchiopexy. J Urol. 2003;;170:2396–2401. [PubMed]

15. Singh KA, Gabriel K. Pediatric musculoskeletal complaints. In: Daniels J, Hoffman MR, editors.Common Musculoskeletal Problems: A Handbook. New York, NY: Springer;; 2010. pp. 79–88.

16. Cattolica EV, Karol JB, Rankin KN, et al. High testicular salvage rate in torsion of the spermatic cord. J Urol. 1982;;128:66–68. [PubMed]

17. Candocia FJ, Sack-Solomon K. An infant with testicular torsion in the inguinal canal. Pediatr Radiol. 2003;;33:722–724. [PubMed]