| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Phillip Stafford, MD | Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Maryland Medical Center, Baltimore, Maryland |

| Katherine M. Prybys, DO | University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland |

Case report

Discussion

Conclusion

ABSTRACT

The urinary tract is an often forgotten and under-appreciated source of infection in anuric hemodialysis patients. Bladder abscess, also called pyocystis, is a severe complication of low urinary flow that can be difficult to detect, leading to delays in treatment and increased morbidity. The emergency physician should maintain a high suspicion for pyocystis, which can be quickly diagnosed by bedside ultrasound. We report a case of a hemodialysis patient with an initially minor presentation who developed sepsis secondary to pyocystis and prostate abscess.

CASE REPORT

A 57-year-old African American male patient with past history of hypertension and long-standing end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on maintenance hemodialysis through a left upper extremity arteriovenous fistula presented to the emergency department (ED) complaining of penile pain and discharge for one day. He denied any other significant complaints, including fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or rectal pain. He reported that he has been anuric for many years, but on the day prior to presentation, the patient began experiencing a scant amount of thick urethral discharge. The patient denies any sexual contact for at least two years, trauma, or any similar episodes in the past.

In the emergency department, initial vital signs were: heart rate 68, blood pressure 149/83, respiratory rate 18, temperature 98.9 Fahrenheit, and oxygen saturation 99% on room air. Abdominal examination found no distention or tenderness, and there was no costovertebral angle tenderness. Genitourinary examination confirmed a scant amount of urethral discharge without any additional discharge or tenderness on penile palpation. There was right-sided inguinal lymphadenopathy. There were no lesions, scrotal tenderness, or scrotal swelling. A digital rectal exam was performed due to concern for prostatitis, which revealed a prostate that was enlarged, boggy, and tender to palpation.

A urethral swab of the discharge fluid was obtained for gram stain, culture, and polymerase chain reaction assay for gonorrhea and chlamydia DNA. Resistance to swab passage in the distal urethra was noted. Due to concern for prostatitis and sexually transmitted infection, the patient was given a single-dose treatment regimen of ceftriaxone, azithromycin, and metronidazole, with a plan to prescribe ciprofloxacin for outpatient treatment of prostatitis. However, approximately 60 minutes after the urethral swab was performed, the patient then developed a large amount of purulent drainage from the urethra, which was cultured. Repeat vital signs at that time revealed a heart rate of 120, blood pressure 160/100, respiratory rate 22, and temperature 101.7 Fahrenheit establishing a diagnosis of early sepsis, which was initially thought to be secondary to pyelonephritis in the setting of anuria.

Intravenous access, labs, and blood cultures were obtained, and the patient was started on vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam. A computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained to evaluate the patient for a differential diagnosis of pyelonephritis, nephroureterolithiasis, and pelvic abscess. The patient was hospitalized, and the departments of urology and nephrology were consulted. Because the bladder had partially decompressed spontaneously, the urologist initially advised against Foley catheter placement in the ED.

CT with intravenous contrast was performed, revealing a heterogeneous, thick walled bladder consistent with pyocystis in the setting of copious urethral discharge of purulent fluid. CT also demonstrated communication between the posterior bladder wall and the seminal vesicles and a large prostatic abscess. After the patient’s admission to the hospital, the urologist placed a Foley catheter for further bladder irrigation and drainage. After successful drainage of the prostatic abscess through a percutaneous drain placed by interventional radiology, the Foley catheter was removed.

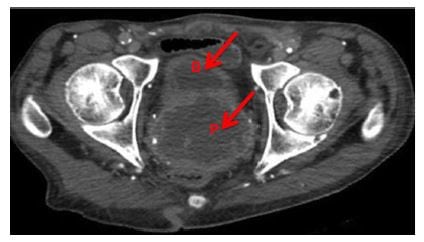

Figure 1

Axial computed tomography demonstrates persistent abscess within the bladder and prostate after spontaneous urethral drainage, with communication between the bladder (B) and prostate (P) abscesses.

Cultures of the discharge fluid and of the prostatic abscess after drain placement both revealed E. coli with resistance to ampicillin, gentamicin, tetracycline, tobramycin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and susceptibility to cephalosporins, carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, and piperacillin/tazobactam. Blood cultures were unremarkable. Stool cultures were performed by the inpatient team, which were also unremarkable. The patient recovered and was discharged on a two-week course of ciprofloxacin with urology follow up.

DISCUSSION

In the United States, ESRD is a growing problem, with 593,000 people being treated for ESRD at the end of 2009.1 This trend represents almost a 600% increase in the prevalence of ESRD over the past 30 years, which is due to the combination of the ability of dialysis therapy to substantially extend patients’ lifetimes and the persistence of poorly controlled hypertension and diabetes in the population.2 By 2011, more than 400,000 of these patients were being treated with hemodialysis.3 Patients with complications of ESRD and hemodialysis are frequently evaluated in EDs. In 2010, there were over one million ED visits by patients on dialysis.4

Infection is a common cause of ED visits among patients with dialysis-dependent ESRD, leading to 0.46 admissions per patient-year.5 These trends are expected to continue, increasing the frequency with which we evaluate and treat patients with complications of ESRD and hemodialysis. By 2015, the prevalence of patients with ESRD has been predicted to exceed 700,000.6

Loss of renal function concomitantly leads to oliguria or anuria, creating defunctionalization and inadequate washout of the urinary bladder due to low flow through the urinary system. This low-output state is a recognized risk factor for bladder complications.7–10

The most common complication of the defunctionalized bladder due to urinary diversion is pyocystis, but the exact incidence of this complication in the anuric hemodialysis-dependent patient population is unknown.11 Pyocystis, also termed vesical empyema, may develop in the defunctionalized bladder due to accumulation of cellular debris and secretions that later become infected because the bladder is not evacuated.7,12 Whereas urinary tract infections consist of inflammation and infection of the organ system, pyocystis represents an evolution of infection into an intravesical abscess due to inadequate urinary flow to maintain bladder washout. For unknown reasons, patients with pyocystis can often present without fever, leukocytosis, or typical symptomatology.8–9 It is postulated that alterations in cell-mediated immunity due to uremia, diabetes and visceral neuropathy, or other chronic disease result in impairment of the patient’s ability to develop inflammatory signs and symptoms, as in this case.13

The rate of pyocystis in patients with supravesical urinary diversion is reported in different studies to be 7%–67% and required emergency cystectomy in up to 30%.12 Complications related to the defunctionalized bladder, including urethral bleeding, urethral pain, spasms, and infection occur in more than 50% of patients.11,12,14–17 Patients with a surgically placed communication between the urinary tract and the external environment are intuitively more prone to infection. However, the urinary system may be an under-appreciated source of significant infections in dialysis patients being evaluated in the ED. Over a three-year period, 11.6% of hemodialysis patients were found to develop symptomatic urinary tract infection, defined as the presence of culture-positive urine accompanied by dysuria, flank pain, suprapubic pain, cloudy urine, hematuria, or fever.18 The urinary system has been implicated as the primary source in 6–10% of cases of bacteremia in dialysis-dependent patients, typically due to gram-negative organisms that are associated with higher mortality.19,20

These data suggest that urinary tract infections tend to develop insidiously, avoiding detection in the ED until they become more advanced. The medical literature on hemodialysis patients with pyocystis contains only case reports and is unable to quantify the incidence and prevalence of this infectious complication.7–9,21,22 We were unable to find any reported cases of pyocystis associated with prostatic abscess in a hemodialysis-dependent patient.

This case highlights the difficulty in establishing timely diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract infections before such complications develop, as this patient was under frequent medical supervision through hemodialysis while his bladder and prostate abscesses progressed. Diagnosis of urinary tract infections in anuric hemodialysis-dependent patients is made more difficult due to the inability to obtain urine for analysis and culture. A lack of accompanying inflammatory signs and symptoms can further cloud the clinical picture.13 Bedside ultrasonography by the emergency physician could easily demonstrate a distended bladder with complex fluid

Figure 2

Sagittal ultrasound of the bladder in a patient with pyocystis reveals complex heterogeneous fluid within the urinary bladder. Reprinted with permission, courtesy Elsevier from Tung and Papanicolaou. J Can Assoc Radiol. 1990.

or perinephric fluid collections.3 Together with the rest of the physical exam, these easily obtained ultrasound findings would help direct the physician’s workup in considering the need for bladder catheterization in an anuric patient or CT of the abdomen and pelvis.

Treatment of pyocystis includes resuscitation and parenteral antibiotics covering gram-negative bacteria. Although oral antibiotics have been effective in treating symptomatic urinary tract infections in the hemodialysis-dependent population,18 the nature of pyocystis as an abscess formed within the bladder necessitates bladder drainage, parenteral antibiotics, and consideration of bladder irrigation with bactericidal solutions.8,9,12,21 Successful treatment has been reported with bladder irrigation solutions containing silver nitrate, chlorhexadine, acetic acid, or nitrofurantoin.12 Further source control may be accomplished by transurethral cystoscopy, suprapubic cystostomy,21,23 Spence urethrovaginal fistula,7 or cystectomy. Cystectomy is avoided where possible, especially in hemodialysis patients in whom future kidney transplantation is considered a possibility.

Complication of the pyocystis with abscess extension into neighboring tissues, as in this case, necessitates further intervention to establish source control. Earlier detection and treatment of the developing pyocystis may have halted progression of infection and spared the patient the morbidity, discomfort, and cost of the prostate abscess and subsequent percutaneous drainage.

CONCLUSION

Hemodialysis patients are frequently evaluated in the emergency department due to severe chronic illness. Pyocystis is a major complication of anuria that can be difficult to detect due to the inability to obtain urine samples and a diminished ability to mount appropriate inflammatory signs and symptoms in chronic dialysis patients. Bedside ultrasonography can be used in the ED to establish a rapid diagnosis and expedite treatment with antibiotics, catheter decompression, and specialist consultation.

Footnotes

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Phillip Stafford, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Maryland Medical Center. Email: pstafford@umem.org 9 / 2014; 15:655 – 658

Submission history: Revision received April 8, 2014; Accepted May 9, 2014

Conflicts of Interest: By the West JEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1 . United States Renal Data System 2011 Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. 2011;

2 . National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse Web site. ;

3 End Stage Renal Disease Network Organization Program Web site. Summary Annual Report. 2010;

4 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Web site. Emergency Department Summary. 2010;

5 . United States Renal Data System 2011 Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. 2011;

6 Gilbertson DT, Liu J, Xue JL Projecting the number of patients with end-stage renal disease in the United States to the year 2015. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005; 16:3736-41

7 Ray P, Taguchi Y, MacKinnon KJ The pyocystis syndrome. Br J Uro. 1971; 43:583-5

8 Lees JA, Falk RM, Stone WJ Pyocystis, pyonephrosis and perinephric abscess in end stage renal disease. J Uro. 1985; 134:716-9

9 Bibb JL, Servilla KS, Gibel LJ Pyocystis in patients on chronic dialysis: a potentially misdiagnosed syndrome. Int Uro and Nephr. 2002; 34:415-8

10 Montgomerie JZ, Kalmanson GM, Guze LB Renal failure and infection. Med. 1968; 47:1-32

11 Adeyoju AB, Lynch TH, Thornhill JA The defunctionalized Bladder. Int Urogynecol J. 1998; 9:48-51

12 Stewart WW, Cass AS, Ireland GW Experience with pyocystis following intestinal conduit diversion. J Uro. 1973; 109:375-6

13 Drutz DJ Altered cell-mediated immunity and its relationship to infection susceptibility in patients with uremia. Dial Transplant. 1979; 8:320-3

14 Lawrence A, Hu B, Lee O Pyocystis after urinary diversion for incontinence – is a concomitant cystectomy necessary?. Uro. 2013; 82:1161-5

15 Guerrier K, Albert DJ, Persky L Experiences with pyocystis. Arch Surg. 1971; 103:63-5

16 Singh G, Wilkinson JM, Thomas DG Supravesical diversion for incontinence: a long-term follow-up. Br J Uro. 1997; 79:348-53

17 Eigner EB, Freiha FS The fate of the remaining bladder following supravesical diversion. J Uro. 1990; 144:31-3

18 Rault R Symptomatic urinary tract infections in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Nephron. 1984; 37:82-4

19 Nsouli KA, Lazarus JM, Schoenbaum SC Bacteremic infection in hemodialysis. Arch Intern Med. 1979; 139:1255-8

20 Keane WF, Shapiro FL, Raij L Incidence and type of infections occurring in 445 chronic hemodialysis patients. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs. 1977; 23:41-7

21 Falagas ME, Vergidis PI Irrigation with antibiotic-containing solutions for the prevention and treatment of infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005; 11:862-7

22 Remer EE, Peacock WF Pyocystis: Two case reports of patients in renal failure. J Emerg Med. 2000; 19:131-3

23 Tung GA, Papanicolaou N Pyocystis with urethral obstruction: percutaneous cystostomy as an alternative to surgery. J Can Assoc Radiol. 1990; 41:350-2