| Authors | Affiliations |

| Christine Riguzzi, MD | Highland Hospital-Alameda Health System, Department of Emergency Medicine, Oakland, California |

| Lia Losonczy, MD, MPH | Highland Hospital-Alameda Health System, Department of Emergency Medicine, Oakland, California |

| Nathan Teismann, MD | UCSF School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, San Francisco, California |

| Andrew A. Herring, MD | Highland Hospital-Alameda Health System, Department of Emergency Medicine, Oakland, California |

| Arun Nagdev, MD | Highland Hospital-Alameda Health System, Department of Emergency Medicine, Oakland, California |

Introduction

Case Report

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

ABSTRACT

Abdominal angioedema is a less recognized type of angioedema, which can occur in patients with hereditary angioedema (HAE). The clinical signs may range from subtle, diffuse abdominal pain and nausea, to overt peritonitis. We describe two cases of abdominal angioedema in patients with known HAE that were diagnosed in the emergency department by point-of-care (POC) ultrasound. In each case, the patient presented with isolated abdominal complaints and no signs of oropharyngeal edema. Findings on POC ultrasound included intraperitoneal free fluid and bowel wall edema. Both patients recovered uneventfully after receiving treatment. Because it can be performed rapidly, requires no ionizing radiation,and can rule out alternative diagnoses, POC ultrasound holds promise as a valuable tool in the evaluation and management of patients with HAE. [West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(7):-0.]

INTRODUCTION

In the emergency department (ED), angioedema may be due to an environmental allergy, adverse reaction to an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I), or more rarely, to hereditary angioedema (HAE). Although most clinicians associate acute attacks of HAE with oropharyngeal edema, acute abdominal pain may be the only presenting symptom. More than 90% of patients with diagnosis of HAE will have recurrent abdominal attacks.1 Acute episodes of abdominal HAE can present with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal tenderness, and can be an under-recognized presentation. Computed tomography (CT), the most common imaging modality used to diagnose abdominal HAE, typically demonstrates thickened bowel wall and ascites in such patients.2 Point-of-care (POC) ultrasound can also be used to identify these findings and has the potential advantages of being rapidly performed at the bedside and not associated with ionizing radiation. Here, we describe the first two cases of acute attacks of abdominal HAE identified with POC ultrasound.

CASE REPORT

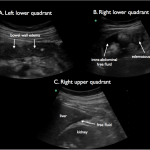

Case 1: A 14-year-old girl with a history of HAE presented to the ED with nausea and abdominal pain for four hours. Two months prior, she had had a similar episode of abdominal pain and was treated as an outpatient with fresh frozen plasma (FFP). Significant clinical findings in the ED included tachycardia, epigastric tenderness, leukocytosis, and elevated hemoglobin. A POC ultrasound was performed, demonstrating free intra-abdominal fluid in Morison’s pouch and in the pelvis (Figure 1). Segments of small bowel appeared edematous with focal areas of increased echogenicity. She was treated with intravenous fluids, pain medications and two units of FFP. The patient was observed on the pediatric service with improvement of clinical symptoms and resolution of the above findings on a repeat consultative ultrasound examination the following day.

Figure 1. Arrows showing free fluid in the pelvis adjacent to the uterus in longitudinal (A) and transverse planes (B) and in Morison’s pouch (C).

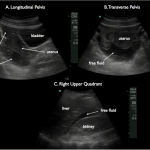

Case 2: A 47-year-old female with known history of HAE presented to the ED with abdominal pain and nausea for 12 hours. She had been hospitalized several times for abdominal angioedema and also required intubation twice for oropharyngeal edema. In the ED, she was found to have moderate tenderness in the lower quadrants with a mild leukocytosis and increased hemoglobin. A POC ultrasound revealed free fluid in Morison’s pouch and her right lower quadrant (Figure 2). In the left lower quadrant, the bowel wall appeared diffusely thickened and echogenic with a narrowed, hypoechoic lumen and surrounding free fluid. During a previous episode of abdominal HAE, she underwent a CT that demonstrated similar findings. She was admitted to the hospital, and by the following day her abdominal pain had significantly improved following treatment with icatibant, and a consultative ultrasound confirmed resolution of the above findings. She was discharged and continued taking her home danazol and folic acid.

Figure 2. Thickened and hypoechoic bowel wall demonstrating edema (A), free fluid surrounding abnormal bowel (B) and free fluid in Morison’s pouch (C).

DISCUSSION

In the above cases, emergency physician-performed POC ultrasound was used to identify intraperitoneal free fluid and bowel wall edema, findings consistent with acute attack of abdominal HAE. HAE is a rare autosomal-dominant disease caused by serum C1 inhibitor deficiency. This deficiency leads to an up-regulation of complement, activating the bradykinin pathway and causing vascular permeability and subsequent mucosal edema. In abdominal HAE, edema in the bowel wall causes fluid to accumulate in the peritoneum, leading to abdominal pain and nausea, and making the diagnosis of HAE possible with POC ultrasound.

Several small studies of ultrasound in abdominal HAE have demonstrated the presence of bowel wall edema with ascites, which appears to correlate with clinical symptoms and response to treatment.3-5 While the use of CT has been reported previously,2 ultrasound has not been described in the emergency medicine literature. In these cases, the emergency physician was able to visualize intraperitoneal free fluid and bowel wall edema with thickening, leading to an expedited diagnosis of abdominal HAE in the ED.

In the cases presented, free fluid was noted in the abdomen, specifically in the right upper quadrant and pelvis. In contrast to intra-abdominal blood, which often contains subtle, granular, internal echoes, the free fluid seen in abdominal HAE should appear completely echolucent, similar to what is seen in patients with ascites. In young women, this feature may allow for differentiation between abdominal HAE and a ruptured ovarian cyst, which may have a similar clinical presentation. In acute abdominal HAE, thickened and edematous bowel wall can also be readily visualized as slightly echolucent and should measure 5mm or greater, from the outer wall to the lumen of the bowel.6

In summary, POC ultrasound allows for a rapid assessment of patients with HAE who present with abdominal complaints and can also be useful in excluding other diagnoses such as biliary disease, ectopic pregnancy, and appendicitis. Risk stratifying these patients early in their clinical course allows for early treatment of what can be a life-threatening presentation. Because of the recurrent nature of abdominal HAE, the use of POC abdominal ultrasound may be able to reduce cumulative ionizing radiation exposure from repeated CT. If further study supports the observations in the above cases, POC abdominal ultrasound may emerge as an ideal initial imaging modality for the evaluation of patient’s with HAE and abdominal pain.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Rick McPheeters, DO

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Christine Riguzzi, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, Highland Hospital-Alameda Health System, 1411 East 31st Street, Oakland, CA 94602-1018. Email: christineriguzzi@gmail.com.

Submission history: Submitted February 27, 2014; Revision received July 5, 2014; Accepted July 22, 2014

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

- Bork K, Meng G, Staubach P, et al. Hereditary angioedema: New findings concerning symptoms, affecting organs, and course. AM J Emerg Med. 2006;119:267-274.

- LoCascio E, Mahler S, Arnold T. Intestinal angioedema misdiagnosed as recurrent episodes of gastroenteritis. West J Emerg Med. 2010;XI(4):391–394.

- Dinkel HP, Maroske J, Schrod L. Sonographic appearances of the abdominal manifestations of hereditary angioedema. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:296–298.

- Farkas H, Harmat G, Kaposi P, et al. Ultrasonography in the diagnosis and monitoring of ascites in acute abdominal attacks of hereditary angioneurotic oedema. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:1225–1230.

- Sofia S, Casali A, Bolondi L. Sonographic findings in abdominal hereditary angioedema. J Clin Ultrasound. 1999;27(9):537–540.

- Brant WE. The Core Curriculum: Ultrasound. Philadephia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001.