| Author | Affiliation |

| Ashley Pilgrim, MD | University of California Davis, Department of Emergency Medicine, Sacramento, California |

| Rachel Russo, MD | University of California Davis, Department of Surgery, Sacramento, California |

| Aimee Moulin, MD | University of California Davis, Department of Emergency Medicine, Sacramento, California |

Introduction

Case Report

Discussion

ABSTRACT

This case outlines the emergency department and surgical course of a 63-year-old male presenting with acute onset abdominal pain. Appendicitis was high on the differential for the treating physician, but after the computed tomography and laboratory evaluation were unremarkable, the patient was discharged only to return the next day. What ensued was one of the rarest cases of missed appendicitis documented in the medical literature.

INTRODUCTION

Acute appendicitis is almost always on the differential for nearly every patient presenting to the emergency department (ED) with abdominal pain. A myriad of decision rules have been created to help guide our diagnostic approach; however, most have proven to be either insensitive, non-specific or too rigorous to be practical in a busy ED setting. Many of us rely on our gestalt and hope that our imaging of choice, often a computed tomography (CT), will help confirm our suspicion. Here we present a case of a 63-year-old male presenting with right lower quadrant pain with a subsequently negative CT found to have an acute ruptured appendicitis on return visit the following day.

CASE REPORT

A 63-year-old male presented to the ED twice in two days with severe abdominal pain. At the first visit, the patient was seen in the ED with initial complaint of acute onset right lower quadrant pain. The pain woke him up from sleep and was described as sharp, 10/10, constant, and worsened by any movement. The patient denied any other associated symptoms, including fevers, vomiting, appetite change, or urinary symptoms. On exam, the patient was afebrile, heart rate of 76, blood pressure of 132/77, and normal respiratory rate and oxygen saturation. He was noted to be grunting due to pain, diffusely tender to palpation in the abdomen but worse in the right lower quadrant, and had a positive obturator sign. He also had a partially reducible, non-tender umbilical hernia.

The patient’s past medical history was significant for atrial fibrillation on Warfarin, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and peptic ulcer disease.

Laboratory findings were unremarkable, including a normal white blood cell count, liver function tests, lipase, and urinalysis.

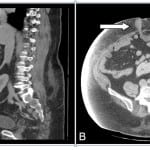

A CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast was performed to rule out appendicitis. Unfortunately, the radiologist was unable to visualize the appendix; however, he commented that there were no secondary signs of appendicitis. The radiologist also noted an incidental finding of a bowel containing umbilical hernia without evidence of strangulation or bowel obstruction (Figure 1). The patient was discharged home after a five-hour observation period in stable condition.

Figure 1. A & B, Arrows illustrating sagital and axial views of appendix entering umbilical hernia sac.

The patient returned to the ED approximately 25 hours after discharge with acutely worsening abdominal pain now primarily focused in the periumbilical region. Further history was limited as the patient was moaning in pain and appeared to be in extremis. The patient was now tachycardic to 103, but otherwise vital signs were within the normal range. On exam, the patient was now noted to have a moderately tender, firm umbilical hernia with overlying skin erythema.

Acute Care Surgery was immediately consulted for concerns of a strangulated umbilical hernia. They were at the bedside within minutes and elected to take the patient to the operating room urgently following Warfarin reversal with fresh frozen plasma.

In the operating room, the hernia sac was opened and found to contain a perforated appendix with abscess formation. The patient was found to have a very long appendix with the tip lying within the umbilical hernia sac, surrounded by thickened omentum (Figure 2). The patient next underwent an open appendectomy with umbilical hernia repair without the use of mesh. The incision was left open to heal by secondary intention. Intraoperative wound cultures were obtained and enterococcus raffinosus and streptococcus anginosus were isolated.

Figure 2. Limited midline laparotomy revealing umbilical hernia sac containing the perforated tip of the appendix. A, Perforation at the tip of the appendix with inflamed mesoappendix within the hernia sac. B, Body of appendix. C, Base of the appendix, joining the cecum.

The patient had a relatively uneventful post-operative course. The patient was discharged five days later with a wound vacuum assisted closure (VAC) in place and given a 10-day course of ciprofloxacin and flagyl. In the following several weeks, the patient was reportedly doing well, but wound VAC remained in place to promote wound healing.

DISCUSSION

The presence of an appendix within a hernia sac is a relatively rare phenomenon. This was described first by Jacques Croissant de Garengeot in 1731 after discovering a vermiform appendix located within a femoral hernia.1 Claudius Amyand four years later described the first known instance of an appendix within an inguinal hernia sac on an 11-year-old boy.2 Appendices located within a femoral hernia or an inguinal hernia sac are now more commonly referred to by their eponyms, de Garengeot and Amyand’s hernias, respectively. The presence of acute appendicitis within an inguinal hernia is reported to be as low as 0.08%.3 The presence of appendicitis within a umbilical hernia is even rarer. To the best of our knowledge, there have been less than a handful of case reports in adults describing the presence of appendicitis within an umbilical or paraumbilical hernia sac. It was first described by Doig4 in 1970, later by Al-Qahtanit5 in 2003, and most recently by Agarwal6 in 2013. All were single-patient case reports. There is only one reported occurrence in the English literature in a child, described in 2008 by Atabek,7 in which he found an acute appendicitis within an umbilical hernia sac in a 25-day-old infant.

The finding of appendicitis within a hernia sac is almost always found in the operating room. Patients usually present with acute onset abdominal pain with exam findings highly suspicious for a strangulated hernia. Hernias are often tender, firm, and may have overlying skin changes. However, if imaging is obtained, there will not be radiologic evidence of a bowel obstruction. Now with the increased use of high resolution CT scanners, it is possible to diagnose appendicitis within a hernia sac prior to the operating room. The first CT radiographic evidence of appendicitis within an umbilical hernia was described by Arnaiz8 in 2006. Unfortunately, this was not the case for our patient whose appendix was not identified on CT from the day prior. Park et al.9 reports the overall sensitivity of CT for diagnosis of acute appendicitis is 96.4%, meaning nearly 4% of acute appendicitis will be missed with CT alone. This highlights not only the importance of a thorough history and physical, but also the importance of providing strict and detailed return precautions for our patients being considered for discharge. Retrospective analysis of the CT on our patient did in fact reveal malrotation, colon isolated to the left hemi-abdomen, and the appendix entering the umbilical hernia with a very small amount of free fluid (Figure 1). It has been hypothesized that external compression of the appendix by the hernia leads to ischemia and subsequent appendicitis. Despite the initial delay in diagnosis, our patient is recovering well.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: John Sarko, MD

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Ashley Pilgrim, MD, 3018 Donner Way, Sacramento, CA 95817. Email: pilgrimashley@gmail.com.

Submission history: January 24, 2014; Revision received June 19, 2014; Accepted July 31, 2014

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

- Salkade PR. De Garengeot’s hernia: an unusual right groin mass due to acute appendicitis in an incarcerated femoral hernia. Hong Kong Med J. 2012;18(5):442-5.

- Montes IS, Deysine M. Spigelian and other uncommon hernia repairs. Surg Clin N Am. 2003;83:1235-53.

- D’Alia C, Lo Schiavo MG, Tonante A, et al. Amyand’s hernia: case report and review of the literature. Hernia. 2003;7:89-91.

- Doig CM. Appendicitis in umbilical hernial sac. Br Med J. 1970; ii:113-114.

- Al-Qahtani HH, Al-Qahtani TZ. Perforated appendicitis within paraumbilical hernia. Saudi Med J. 2003; 24:1133-4.

- Agarwal N. Appendicitis in paraumbilical hernia mimicking strangulation: a case report and review of the literature. Hernia. 2013;17(4):531-2.

- Atabek C, Sürer I, Deliağa H, et al. Appendicitis within an umbilical hernia sac: previously unreported complication in children. TJTES. 2008;14(3):245-246.

- Arnaiz J. Unusual perforated appendicitis within umbilical hernia: CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31(6):691-3.

- Park JS, Jeong JH, Lee JI, et al. Accuracies of diagnostic methods for acute appendicitis. Am Surg. 2013; 79(1):101-6.