| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Nancy J. Thompson, PhD, MPH | Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University,Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Atlanta, Georgia |

| Robin E. McGee, MPH | Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University,Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Atlanta, Georgia |

| Darren Mays, PhD, MPH | Georgetown University Medical Center,Department of Oncology,Washington, DC |

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

The purpose of this study was to examine racial/ethnic disparities in being forced to have sexual intercourse against one’s will, and the effect of substance use on these disparities.

Methods:

We analyzed data from adolescent women participating in the Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Bivariate associations and logistic regression models were assessed to examine associations among race/ethnicity, forced sex, and substance use behaviors.

Results:

Being forced to have intercourse against one’s will and substance use behaviors differed by race/ethnicity. African Americans had the highest prevalence of having been forced to have sexual intercourse (11.2%). Hispanic adolescent women were the most likely to drink (76.1%), Caucasians to binge drink (28.2%), and African Americans to use drugs (44.3%). When forced sexual intercourse was regressed onto both race/ethnicity and substance use behaviors, only substance use behaviors were significantly associated with forced sexual intercourse.

Conclusion:

Differences in substance use behaviors account for the racial/ethnic differences in the likelihood of forced sexual intercourse. Future studies should explore the cultural and other roots of the racial/ethnic differences in substance use behavior as a step toward developing targeted interventions to prevent unwanted sexual experiences.

INTRODUCTION

The United States (U.S.) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines sexual violence as nonconsensual completed or attempted penetration, unwanted non-penetrative sexual contact, or noncontact acts (e.g., verbal sexual harassment, being flashed, being forced to look at sexual materials) by any perpetrator.1 Sexual violence is a major public health concern, in part because of its prevalence, and also because it results in quantifiable psychological and physical injuries, as well as other long-term health impacts.2

The most likely victims of sexual violence are young and female.2 The vast majority of victims experience their first sexual assault before 18 years old,4 and a recent CDC report stated that 42.2% of first experiences of forced sexual intercourse occur during adolescence.5 Overall, the prevalence of unwanted sexual experiences among adolescent women is reported to be between 13.5% and 30.0%.3,4 Although the prevalence estimates vary due to measurement and data collection issues, sexual assault is most likely under-reported.3 Experiences of sexual assault, in particular, during adolescence are associated with a number of adverse outcomes, including re-victimization, increased prevalence of mental disorders, and risky health behaviors.5–15

Increasing diversity of the U.S. population requires a better understanding of risk factors for adverse outcomes, such as sexual assault, by race/ethnicity. For adult women, recent data from the CDC report lifetime prevalence of rape as about 1 in 5 for African Americans (22.0%) and whites (18.8%), and 1 in 7 for Hispanics (14.6%).5 Some studies have shown that the prevalence of forced sexual intercourse among adolescents differs by racial and ethnic groups, while others have found no differences.5,8,16–19In the studies that find differences, the results are mixed. For instance, 1 study only found differences among race/ethnic groups for adolescent men, but not adolescent women.17 In another study, African American adolescents reported the highest proportion of forced sexual intercourse, which is consistent with results from the National Violence Against Women Survey showing that black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaskan Native women are at greater risk for rape victimization than white women.2,16,18 Since race/ethnicity is, at best, a marker for those with a high risk, it is important to explore whether particular causal risk factors are associated with race/ethnicity, and whether these risk factors may explain differences in the rates of forced sexual intercourse among the members of various racial/ethnic groups. Identifying the causal factors will enable development of preventive interventions that can then be targeted to the groups at risk.

Substance use is one candidate risk factor as it is a common behavior among teens and is reported to vary by race/ethnicity. Binge drinking, or heavy episodic drinking, is most often defined as consuming 5 or more drinks during 1 occasion. This behavior occurs frequently among younger persons; 7.3% of women aged 12 to 17 years in 2010 reported binge drinking in the previous month.20 This behavior also differs by race/ethnicity. For example, Asian and African Americans tend to report lower levels of binge drinking than other groups.20,21 Compared with alcohol use, illicit drug use is less prevalent, with 19.4% of adolescents reporting past year use.20 However, compared with binge drinking, reported illicit drug use among women between the ages of 12 to 17 is considerably higher (19.4%).20 African Americans report similar levels of drug use compared with whites and Hispanics, while Asians report lower levels.20

Cross-sectional studies of substance use and forced sexual intercourse find that they frequently co-occur. For example, adolescent women who report drug use, such as marijuana and other illicit drugs, are significantly more likely to report sexual victimization.9,18 Similar results are found for alcohol use, especially binge drinking.1,17 Research about the causal relationship between forced sexual intercourse and substance use suggests bi-directionality.22 More specifically, given the emotional impact of forced sexual intercourse, it can increase future alcohol and drug use.23,24 On the other hand, longitudinal studies of adolescent women suggest that alcohol and drug use increase risk for sexual victimization.9,25 In fact, a national survey found that 1 per 1000 adolescents reported having experienced a drug- or alcohol-facilitated rape by a dating partner, and 2% of college students were victims of alcohol-related sexual assault or date rape.26–27 Adolescent women who experience drug- or alcohol-facilitated rape are more likely to report having abused alcohol or used drugs in the past year compared to adolescent women who report other types of sexual assault.28 Alcohol and drug use may place adolescents in high-risk environments where forced sexual intercourse is more likely to occur. Alcohol consumption influences sexual risk behavior, reducing perceptions of individual risk, which may provide increased opportunity for experiencing sexual assault among adolescents who drink alcohol.29 Using alcohol and being in risky situations may be the two risk factors that best predict forced sexual intercourse.2,30The literature cited above suggests that substance use may be an important risk factor confounding the relationship between race/ethnicity and forced sexual intercourse. Most research investigating outcomes associated with forced sexual intercourse controls for race/ethnicity, but very little has examined racial and ethnic differences in sexual victimization, especially while controlling for the effects of other risk factors.13,22,31 Furthermore, researchers have called for a better understanding of the role of substance use in forced sexual intercourse,3 particularly among racial and ethnic groups.18 In response, this research was designed to explore the following questions:

- Does the prevalence of forced sexual intercourse vary by race/ethnicity among adolescent women?

- Does drinking behavior and drug use vary by race/ethnicity among adolescent women?

- Does racial/ethnic variation in forced sexual intercourse among adolescent women persist when drinking behavior and drug use are controlled?

METHODS

The Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) is a biannual survey conducted by the CDC to monitor the health behaviors of high school students in the U.S. Data on forced sexual intercourse, binge drinking, and drug use, as well as race/ethnicity were available from the 2009 YRBS.

The YRBS selects respondents based on a 3-stage, cluster sample design through proportional probability methods used to select counties, schools, and then classrooms. Before administering the survey, local parental permission procedures were followed, and students were informed that their participation was anonymous and voluntary. The self-administered questionnaire was completed in the students’ classrooms. The 2009 YRBS public-use data file included responses from 16,410 adolescents, including 7,816 women in the weighted sample. However, only women who responded to the questions about forced sex, drinking behavior, drug use, and the demographic variables comprised the sample for this study. Additionally, respondents who reported sexual intercourse before the age of 13 were removed from the sample in an effort to eliminate cases of child sexual abuse.32 The final sample consisted of 5,966 adolescent women.

Measures

Questions from the YRBS were used to investigate the relationship between race/ethnicity and forced sexual intercourse, race/ethnicity and alcohol and drug use, and whether alcohol and drug use confound the relationship between race/ethnicity and forced sexual intercourse. The YRBS is reported to be a reliable data source of adolescent health behaviors.33

Forced sexual intercourse was the dependent variable and coded as positive if the participant responded “Yes” to the question, “Have you ever been forced to have sexual intercourse when you did not want to?”

Race/ethnicity was grouped into four dummy-coded variables (i.e., yes/no): African American, Asian (Asian and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander), Hispanic (Hispanic and Multiple-Hispanic), and Caucasian. In the logistic regression analyses, Asian race/ethnicity was selected as the referent group because this group had the lowest prevalence of forced sexual intercourse, alcohol use, and drug use.

Drinking behavior was assessed using 3 questions: “During your life, on how many days have you had at least 1 drink of alcohol?”, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have at least 1 drink of alcohol?”, and “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have 5 or more drinks of alcohol in a row, that is, within a couple of hours?” Respondents were placed into 1 of 4 categories: binge drinker, non-binge drinker, former drinker, and abstainer. Binge drinkers responded that they had drunk more than 5 drinks in a row on 1 or more days in the past 30 days. Non-binge drinkers had one or more days of drinking at least 1 drink of alcohol, but not more than five drinks in a row on one or more days in the past 30 days. Former drinkers were individuals who responded that they had drunk alcohol within their lifetime, but not within the last 30 days, and abstainers were individuals who did not meet any of the above definitions. The category of abstainers was the referent group for the drinking behavior variables.

Drug use was operationalized with a composite variable, due to the low prevalence of use of many of the individual drugs. Seven questions in the YRBS ask about lifetime use of drugs, including marijuana, cocaine, glue or aerosol spray cans, heroin, methamphetamines, ecstasy, or injection drugs. The variable was dichotomous, with lifetime drug use or no lifetime drug use as the two categories. No lifetime drug use was the referent category for the logistic regression analyses.

Age was grouped into five categories: 14 and younger, 15, 16, 17, and 18. Eighteen was the referent group for the logistic regression analyses.

Statistical Analysis

Using SPSS 19, we completed the analyses with the weighted, public-use YRBS data files. First, we used descriptive and bivariate statistics to assess whether the prevalence of forced sex, alcohol use, and drug use differed by race/ethnicity. Then, we created 2 logistic regression analyses to examine whether racial variation in forced sexual intercourse persisted when controlling for the effects of drug and alcohol use variables. The first logistic regression model assessed the relationship between forced sex and race/ethnicity, when controlling for age. The second logistic regression model assessed whether controlling for alcohol and drug use altered the relationship between forced sex and race/ethnicity. We assessed significance of the model using the Omnibus Test, and Fit of the Model using the Hosmer and Lemeshow Chi Square.34 Collinearity was assessed by examining the correlations between the independent variables. Age was controlled in each of the regression analyses.

RESULTS

Research Question 1

Overall, the prevalence of forced sexual intercourse among adolescent women was 8.9%. Prevalence differed by race/ethnicity (X2(3)=11.94, p=0.008), with 11.2% of African Americans, 8.8% of Caucasians and Hispanics, and 4.0% of Asians reporting forced sexual intercourse.

Research Question 2

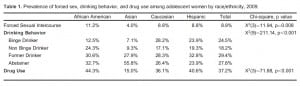

Table 1 presents the prevalence of forced sexual intercourse, drinking behavior, and drug use by race/ethnicity. The prevalence of alcohol use differed significantly based on adolescents’ race/ ethnicity (X2(9)=211.14, p<0.001). Across all groups, the prevalence of binge drinking was 24.5%. Caucasians had the highest prevalence of binge drinking (28.2%), followed by Hispanics (23.9%), and African Americans (12.5%). Asians had the lowest prevalence (7.1%). Asians had the highest prevalence (55.8%) of the referent abstainer category, and Hispanics had the lowest prevalence (23.9%). In total, 27.8% of adolescent women reported abstaining from alcohol.

More than one-third (37.2%) of adolescent women reported lifetime drug use. African Americans had the highest prevalence of drug use (44.3%), whereas Asians had the lowest prevalence of drug use (15.0%). Again, the racial/ethnic groups were significantly different from each other (X2(3)=71.88, p<0.001).

Research Question 3

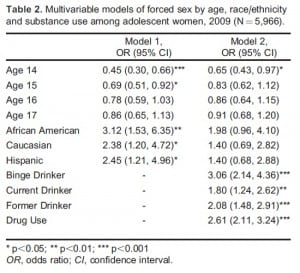

The first multivariable model examined the risk for forced sexual intercourse by race/ethnicity, controlling for age (Table 2). The model was significant (X2(7)=34.29, p<0.001) and demonstrated a good fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow X2(8)=4.85, p=0.773). Compared with Asians, African Americans (OR = 3.12 [95% CI 1.53, 6.35]), Caucasians (OR=2.38 [95% CI 1.20, 4.72]) and Hispanics (OR=2.45 [95% CI 1.21, 4.96]) had significantly higher odds of reporting forced sexual intercourse.

The second model (Table 2), controlling for drinking behavior and drug use as well as age, also was significant (X2(11)=272.25, p<0.001) and demonstrated a good fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow X2(8)=10.64, p=.223). With drinking behavior and drug use controlled, race/ethnicity was no longer significant, but each of the drinking behavior variables was. Binge drinkers had three times greater odds, and current or former drinkers had about two times greater odds of being forced to have sexual intercourse against their wills than abstainers. Additionally, those who reported any lifetime drug use had about two-and-one-half times the odds of being forced to have sex against their wills than those who never used drugs.

DISCUSSION

Summary of Findings

Using recent national data, the likelihood of adolescent women being forced to have sexual intercourse against one’s will differed by race/ethnicity. This differs from the results of Howard and Wang,17 which showed differences among race/ethnic groups for adolescent men, but not women. According to the current study, the greatest likelihood of forced sexual intercourse among adolescent women was reported by African Americans, and the lowest likelihood by Asians (which included Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders). Several prior studies have reported the highest rate of forced sexual intercourse among African-American adolescent and adult women.5,16,18

The likelihood of drinking alcohol and using drugs also differed by race/ethnicity. While Hispanics were the most likely to report having had a drink at some point in their lives, Caucasians were the most likely to report binge drinking in the past month; Asians were the most likely to report never having drunk alcohol. Like prior studies, we found that Asians and African Americans reported lower levels of binge drinking compared with Caucasians and Hispanics.20,21 In contrast to data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) showing that African Americans reported similar levels of drug use compared with whites and Hispanics, however, we found that these groups differed; African Americans had the highest rate of lifetime drug use followed by Hispanics and then Caucasians.20 As in the SAMHSA data, however, Asians in this study reported lower levels of drug use.

Results of the multivariable model demonstrated, once substance use was controlled, racial/ethnic differences were no longer significant. This indicates that it is the risk factor of substance use, either alcohol or drugs, that explains much of the variation in prevalence of forced sexual intercourse by racial/ethnic group.

Implications

The presence of a disparity by race/ethnic group in the likelihood of being forced to have intercourse against one’s will can be used to develop preventive interventions targeted toward those at greatest risk, but race/ethnicity is neither the cause of the problem nor a modifiable risk factor amenable to intervention. The finding that substance use is a more probable causal factor associated with unwanted sexual experiences provides direction for the content of future preventive interventions. Among the adolescent women studied, Caucasians were the most likely to binge drink, Hispanics the most likely to drink alcohol, and African Americans the most likely to use drugs. Identifying the cultural and other roots of these differences in substance use behavior could be an important step toward targeting interventions to prevent unwanted sexual experiences.

LIMITATIONS

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, while the YRBS is designed to be representative of the adolescent population of the U.S., the sampling frame does not include adolescents who do not attend school, limiting the ability to generalize the data. In addition, the data are cross-sectional, so it is not possible to determine whether substance use preceded forced sexual intercourse, or the reverse. From the analyses, however, we do know that substance use is a stronger associate of forced sex than is race/ethnicity, which was the objective of this paper. Furthermore, the YRBS survey is based on self-reported respondent behavior, which has some limitations with respect to validity.35 These limitations are cognitive (e.g., problems with recall, or failure to comprehend the question) and situational (e.g., desire to respond socially, attention seeking, and concerns about stigma). Studies of self-reported assessments of substance use by adolescents suggest that it is not greatly under-reported, but sexual activity is more subject to self-report bias.35 Being forced to have sexual intercourse against one’s will is a very sensitive experience and may particularly be affected by situational influences, although this measure was found to have substantial reliability using 1999 YRBS data.33

CONCLUSION

We found that the prevalence of being forced to have sexual intercourse against one’s will differed for different racial and ethnic groups, with African Americans having the greatest likelihood. We also found that substance use and patterns of substance use varied by race/ethnicity and that this behavior accounted for the racial/ethnic differences in being forced to have sexual intercourse against one’s will. Future research should explore the cultural and other roots of substance use behavior among adolescent women from varying racial and ethnic groups as a step toward intervening to reduce unwanted sexual experiences.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Monica H Swahn, PhD, MPH

Submission history: Submitted January 17, 2012; Revision received March 8, 2012; Accepted March 17, 2012

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

DOI: 10.5811/westjem.2012.3.11774

Address for correspondence: Nancy J. Thompson PhD MPH

Department of Behavioral Sciences & Health Education, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University. 1518 Clifton Road NE, Atlanta, GA 30322

Email: nthomps@emory.edu

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with respect to this article. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

REFERENCES

1. Basile KC, Saltzman LE. Sexual Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control;; 2002.

2. Basile KC, Smith SG. Sexual Violence Victimization of Women. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2011;5:407–17.

3. Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Childhood and adolescent sexual abuse and subsequent sexual risk behavior: Evidence from controlled studies, methodological critique, and suggestions for research. Clin Psych Review. 2008;28:711–35.

4. Masho SW, Ahmed G. Age at sexual assault and posttraumatic stress disorder among women: prevalence, correlates, and implications for prevention. J Womens Health. 2007;16:262–71.

5. Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. The National Intimiate Partner and Sexual Violenc Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;; 2011.

6. Elliott DM, Mok DS, Briere J. Adult sexual assault: prevalence, symptomatology, and sex differences in the general population. J Trauma Stress. 2004;17:203–11. [PubMed]

7. Humphrey JA, White JW. Women’s vulnerability to sexual assault from adolescence to young adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27:419–24. [PubMed]

8. Muram D, Hostetler BR, Jones CE, et al. Adolescent victims of sexual assault. J Adolesc Health.1995;17:372–75. [PubMed]

9. Raghavan R, Bogart LM, Elliott MN, et al. Sexual victimization among a national probability sample of adolescent women. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36:225–32. [PubMed]

10. Molnar BE, Buka SL, Kessler RC. Child sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Pub Health. 2001;91:753–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

11. Spataro J, Mullen PE, Burgess PM, et al. Impact of child sexual abuse on mental health: prospective study in males and females. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:416–21. [PubMed]

12. Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D. Date violence and date rape among adolescents: associations with disordered eating behaviors and psychological health. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26:455–73. [PubMed]

13. Basile KC, Black MC, Simon TR, et al. The Association between Self-Reported Lifetime History of Forced Sexual Intercourse and Recent Health-Risk Behaviors: Findings from the 2003 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39 752.e751-57.

14. Lang DL, Sales JM, Salazar LF, et al. Rape Victimization and High Risk Sexual Behaviors: A Longitudinal Study of African-American Adolescent Females. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:333–42.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

15. Young MED, Deardorff J, Ozer E, et al. Sexual Abuse in Childhood and Adolescence and the Risk of Early Pregnancy Among Women Ages 18–22. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49:287–93. [PubMed]

16. Crouch JL, Hanson RF, Saunders BE, et al. Income, race/ethnicity, and exposure to violence in youth: Results from the national survey of adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology.2000;28:625–41.

17. Howard DE, Wang MQ. Psychosocial correlates of U.S. adolescents who report a history of forced sexual intercourse. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36:372–79. [PubMed]

18. Rickert VI, Wiemann CM, Vaughan RD, et al. Rates and Risk Factors for Sexual Violence Among an Ethnically Diverse Sample of Adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:1132–9. [PubMed]

19. Freeman DH, Temple JR. Social Factors Associated with History of Sexual Assault Among Ethnically Diverse Adolescents. J Fam Violence. 2010;25:349–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

20. SAMHSA. 2010 National Survey on Drug Use & Health: Detailed Tables. 2010; Available at :http://oas.samhsa.gov/NSDUH/2k10NSDUH/tabs/Sect2peTabs43to84.htm – Tab2.43B. Accessed November 7, 2011.

21. Wu L-T, Woody GE, Yang C, et al. Racial/Ethnic Variations in Substance-Related Disorders Among Adolescents in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:1176–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

22. Champion HLO, Foley KL, Durant RH, et al. Adolescent sexual victimization, use of alcohol and other substances, and other health risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:321–28. [PubMed]

23. Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Saunders B, et al. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: data from a national sample. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:19–30. [PubMed]

24. Rothman EF, Edwards EM, Heeren T, et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences Predict Earlier Age of Drinking Onset: Results From a Representative US Sample of Current or Former Drinkers. Pediatrics.2008;122:e298–304. [PubMed]

25. Howard D, Qiu Y, Boekeloo B. Personal and social contextual correlates of adolescent dating violence. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33:9–17. [PubMed]

26. Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Ruggiero KJ, Danielson CK, et al. Prevalence and correlates of dating violence in a national sample of adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:755–62.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

27. Hingson RW. Magnitude and prevention of college drinking and related problems. Alcohol Research & Health. 2010;33:45–54.

28. McCauley JL, Conoscenti LM, Ruggiero KJ, et al. Prevalence and correlates of drug/alcohol-facilitated and incapacitated sexual assault in a nationally representative sample of adolescent girls. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2009;38:295–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

29. Fromme K, D’Amico E, Katz E. Intoxicated sexual risk taking: An expectancy or cognitive impairment explanation. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:54–63. [PubMed]

30. Ullman SE. A critical review of field studies on the link of alcohol and adult sexual assault in women. Aggress Violent Behav. 2003;8:471–86.

31. Nguyen HV, Kaysen D, Dillworth TM, et al. Incapacitated Rape and Alcohol Use in White and Asian American College Women. Violence against Women. 2010;16:919–33. [PubMed]

32. Pereda N, Guilera G, Forns M, et al. The prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: A meta-analysis. Clin Psych Rev. 2009;29:328–38.

33. Brener ND, Kann L, McManus T, et al. Reliability of the 1999 Youth Risk Behavior Survey Questionnaire. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:336–42. [PubMed]

34. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 4th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon;; 2001.

35. Brener ND, Billy JOG, Grady WR. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: Evidence from the scientific literature. J Adolesc Health.2003;33:436–57. [PubMed]