| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Catherine Finneran, MPH | Emory University, Rollins School of Public Health, Hubert Department of Global Health, Atlanta, Georgia |

| Rob Stephenson, PhD | Emory University, Rollins School of Public Health, Hubert Department of Global Health, Atlanta, Georgia |

Introduction Methods Results Discussion Conclusion

ABSTRACT

Introduction Despite several recent studies documenting high rates of intimate partner violence (IPV) among gay and bisexual men (GBM), the literature is silent regarding GBM’s perceptions of IPV within their community. We examine GBM’s perceptions of same-sex IPV: its commonness, its severity, and the helpfulness of a hypothetical police response to a GBM experiencing IPV.

Methods: We drew data from a 2011 survey of venue-recruited GBM (n=989). Respondents were asked to describe the commonness of IPV, severity of IPV, and helpfulness of a hypothetical police response to IPV among GBM and among heterosexual women. We fitted a logistic model for the outcome of viewing the police response to a gay/bisexual IPV victim as less helpful than for a female heterosexual IPV victim. The regression model controlled for age, race/ethnicity, education, sexual orientation, employment status, and recent receipt of physical, emotional, and sexual IPV, with key covariates being internalized homophobia and experiences of homophobic discrimination.

Results: The majority of respondents viewed IPV among GBM as common (54.9%) and problematic (63.8%). While most respondents had identical perceptions of the commonness (82.7%) and severity (84.1%) of IPV in GBM compared to heterosexual women, the majority of the sample (59.1%) reported perceiving that contacting the police would be less helpful for a GBM IPV victim than for a heterosexual female IPV victim. In regression, respondents who reported more lifetime experiences of homophobic discrimination were more likely to have this comparatively negative perception (odds ratio: 1.11, 95% confidence interval: 1.06, 1.17).

Conclusion: The results support a minority stress hypothesis to understand GBM’s perceptions of police helpfulness in response to IPV. While IPV was viewed as both common and problematic among GBM, their previous experiences of homophobia were correlated with a learned anticipation of rejection and stigma from law enforcement. As the response to same-sex IPV grows, legal and health practitioners should ensure that laws and policies afford all protections to GBM IPV victims that are afforded to female IPV victims, and should consider methods to minimize the negative impact that homophobic stigma has upon GBM’s access of police assistance.

INTRODUCTION

Recent studies suggest that gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) experience intimate partner violence (IPV) at rates comparable to or higher than those documented among women.1–3 Current estimates indicate that approximately 25–50% of United States gay and bisexual men report experiencing physical IPV and 12–30% report experiencing sexual IPV.1,2,4–6 Despite a nascent increase in IPV studies among MSM, same-sex IPV continues to be markedly under-researched, particularly when compared to the vast body of literature regarding male-perpetrator/female-victim IPV.7,8

As the extent of same-sex IPV among gay, bisexual, and other MSM is beginning to be documented in the literature, many facets of IPV among MSM remain unaddressed. Published studies have, in general, sought to determine IPV prevalences, typologies, demographic correlates, and health sequela.7 The literature is comparatively silent, qualitatively and quantitatively, as to the experiences of survivors of same-sex IPV. There is also a lack of studies as to the perceptions of gay, bisexual, and other MSM regarding the extent of IPV in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities. Specifically, we find no published studies that examine gay and bisexual men’s perceptions of the commonness, severity, and helpfulness of a police response to IPV within their communities – areas that have been examined in great detail for male-perpetrator/female-victim IPV. Indeed, it remains unknown to what extent same-sex IPV is reported to any part of the legal system; nor are there data regarding the experiences of survivors of same-sex IPV who do contact the police.

What is known about perceptions of police response to IPV comes entirely from research drawn from samples of women. Although IPV is thought to be among the crimes most commonly reported to law enforcement, it is estimated that a minority of IPV survivors report to the police, and that only a fraction of reported crimes result in the arrest of the perpetrator of the violence.9,10–12 Indeed, the use of contacting the police in preventing future victimization is in dispute, as is the efficacy of so-called “no drop” policies in which perpetrators of partner violence are always prosecuted.11–13 Not all women who contact the police want their abusive partners to be arrested, and women who do contact the police often fear reprisal in the form of revictimization.14,15

Multiple researchers have examined what factors make women more or less likely to contact the police in cases of IPV; other have focused on the other areas of support, including social support, that women access in addition to or in place of police assistance.16,17 Several studies have outlined dilemmas that IPV survivors face when choosing whether or not to contact the police (e.g., possible removal of children from the home, loss of economic resources, shame/humiliation from the abuse becoming public) and barriers faced after the police have been contacted (e.g., being disbelieved, having the situation dismissed/minimized, being wrongly arrested after acts of self-defense).14,18,19 Women’s satisfaction with police response ranges widely in the literature, being categorized as negative to neutral to slightly positive.20,21 Moreover, survivors of IPV have been shown to be more likely to contact the police in cases of future victimization if the response to their initial contact is positive.22

Much has also been written about the role of police legitimacy in influencing when and if survivors of IPV choose to seek police intervention.23,24 Police legitimacy, which in its broadest conceptualization refers both to the authority afforded to the police by the public as well as to the factors that influence the affording of that authority, is understood as being paramount to maintaining social order by encouraging law-abiding behaviors, compliance with police directives, and cooperation with investigations (e.g., reporting a crime).25 Central to police legitimacy is the role of procedural justice, that is, whether or not actions taken by the police are viewed as appropriate, fair, and just.25,26 While little data exist regarding perceptions of police legitimacy among gay and bisexual men, unfair or homophobic treatment of gay and bisexual men by the police could lessen the legitimacy of police and potentially lead to reduced reporting of IPV. Indeed, this phenomenon has been documented among lesbian/gay women, as anticipation of homophobia and stigma by police officers during a police response has been shown to contribute to a reluctance to contact the police when experiencing IPV.14

In addition to the aforementioned lack of research regarding IPV among gay/bisexual men, there is also a lack of literature examining how other factors, such as factors unique to the sexual minority status of gay individuals, would impact the prevalence of, incidence of, or gay/bisexual men’s perceptions of IPV. Meyer27,28 seminally theorized that all of these other factors, when combined, could be understood asminority stress. The theory of minority stress posits that the excess stressors experienced by minority persons are both unique to their minority statuses and additive in nature. Minority stress theory, which now has empirical support in a vast array of subjects, is described by Kaschak37 as creating a “double closet” – that is, LGBT persons who are experiencing partner violence face discrimination borne from both homophobia (internal and external) and from the stigma of being a victim of partner violence.37–50

This study, therefore, has multiple objectives. First, we will describe, for the first time in the literature, the perceptions of gay/bisexual men regarding IPV within their communities, both separately and in comparison to their perceptions for IPV within heterosexual communities. Second, we will examine to what extent both the internal and external forces of minority stress impact gay/bisexual men’s perceptions of IPV, with a particular focus on their understanding of the helpfulness of contacting the police in the case of a hypothetical gay/bisexual man experiencing IPV. A better understanding of factors that influence these decision-making processes will enable all parties that respond to partner violence, including law enforcement agencies and community organizations, to improve their policies and practices in order to reach and serve gay/bisexual male survivors of IPV.

METHODS

Emory University’s ethics committee approved this study. We systematically recruited sexually active MSM over the age of 18 over 5 months in 2011 in Atlanta, Georgia, using venue-based sampling.29Venue-based sampling is a derivative of time-space sampling in which sampling occurs within prescribed blocks of time at particular venues. As a method to access hard-to-reach populations, venue-based recruitment is a process by which a sampling frame of venue-time units is created through formative research with key informants and community members. To reach a diverse population of gay and bisexual men in the Atlanta area, the venue sampling frame used for this study consisted of a wide variety of over 160 gay-themed or gay-friendly venues, including Gay Pride events, gay sports teams events, gay fundraising events, downtown areas, gay bars, bathhouses, an AIDS service organization, an MSM-targeted drop-in center, gay bookstores, restaurants, and urban parks.

Study staff briefly interviewed potential participants outside venues, and eligible men were given information on how to complete the study survey. Men were eligible for the study if they reported identifying as gay/homosexual or bisexual, being aged 18 or older, living in the Atlanta metro area, and having had sex with a man in the previous 6 months. Eligible men who were interested in study participation were given a card with a unique identifier that unlocked a web-based survey. The survey covered several domains and assessed perceptions of 3 components of IPV among gay/bisexual men: the severity of partner violence (“How big of a problem do you think partner violence is among gay/bisexual men?”), commonness of partner violence (“How common do you think partner violence is among gay/bisexual men?”), and helpfulness of a police response (“If a gay/bisexual man were experiencing partner violence and contacted the police, how helpful do you think the police would be in assisting him?”). These 3 perceptions were also assessed for heterosexual women. Each question was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale, after which responses were coded into positive, neutral, or negative – for example, in response to police helpfulness, ‘very helpful‘ and ‘helpful,’ ‘neither helpful nor unhelpful,’ and ‘unhelpful’ and ‘very unhelpful.’

We quantified internalized homophobia using a subset of 20 items from the Gay Identity Scale, a validated scale that assesses acceptance of homosexual feelings and thoughts, as well as how open a respondent is about his homosexuality with family, friends, and associates.30 From these data, we created an index variable of internalized homophobia. No points were added to the index for neutral responses to any scale item. Positive point values were assigned to agreement with internally homophobic sentiments, and negative points were assigned for agreement with statements of gay pride. Thus, increasing index score was correlated to a decreased amount of pride and acceptance of homosexual thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. We added 40 points to each scale to shift the range from –40 –40 to 0 – 80.

We assessed experiences of homophobic discrimination by creating an index scale of reported responses to 11 possible experiences of discrimination due to sexual orientation based on previous studies: being made fun of as a child, experiencing violence as a child, being made fun of as an adult, experiencing violence as an adult, hearing as a child that gay men would grow up alone, hearing as a child that gays are not normal, feeling that your gayness hurt your family as a child, ever having to pretend to be straight, experiencing job discrimination, and having to move away from family.31 Respondents were awarded 1 point for each endorsed response, creating a scale ranging from 0–11.

We assessed recent experience of sexual, physical, and emotional IPV (i.e., within the past 12 months) using the short-form Conflicts Tactics scale (R-CTS), an index of 11 different forms of partner violence across 3 domains: emotional IPV (being called fat or ugly, having something belonging to you destroyed, being accused of being a lousy lover), physical IPV (being threatened to be hit or to have something thrown at you, having something that could hurt thrown at you, being pushed or shoved, being punched or hit with something that could hurt, being slammed up against a wall, being beat up, being kicked), and sexual IPV (having threats used against you to force you to have oral or anal sex).32–34 Participants who indicated that they had experienced any item within an IPV category were classified as having recently experienced that form of IPV; forms of IPV were not mutually exclusive.

Differences in perceptions of IPV for heterosexual women versus gay men were assessed using chi-square testing. Specifically, a comparative analysis identified whether a respondent held identical or disparate perceptions of each of the 3 facets of IPV. If a respondent indicated disparate perceptions, we also recorded the directionality of this difference. Thus, a participant who viewed IPV both among gay/bisexual men and among heterosexual women as not a problem was coded as having an identical response. We identified correlates of a comparatively negative view of police helpfulness using bivariate chi-square analyses and by creating a logistic regression model. The model included age (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, and >44), race/ethnicity (white non-Hispanic, African- American/black non-Hispanic, and Latino/Hispanic or Other), sexual orientation (gay/homosexual or bisexual), education level (high school or less, some college or 2-year degree, or college/university or more), employment status, and receipt of emotional, physical, and sexual IPV in the past 12 months, with the key covariates of interest being the indices of internalized homophobia and homophobic discrimination.

RESULTS

Of 4,903 men approached during venue time-space sampling, 2,936 (59.9%) agreed to be screened for the study, 71.3% of whom (n= 2,093) were eligible for study participation. Of eligible men, 1,965 (93.9%) were interested in study participation. A total of 1,075 men completed the survey; thus 21.9%of men approached and 51.4%of eligible men completed the survey. Of all survey responses, 989 had complete data for all covariates of interest and were included in the analysis. There were no significant (α = 0.05) differences in either exposures or outcomes based upon inclusion in analysis versus exclusion for incomplete data. The sample was predominately young (51% under 35 years of age), gay-identified (11% bisexual-identified), racially diverse (54% non-white), educated (48% college or more), and part- or full-time employed (77%) (Table 1). Approximately one-quarter (24.3%) of the sample reported positive HIV status, and 37.3% of the sample reported having 3 or more anal sex partners in the previous 6 months. Emotional IPV was the most commonly reported form of IPV (24.5%), while nearly one in 5 respondents (17.6%) reported recent physical IPV and approximately one in 20 (4.5%) reported recent receipt of sexual IPV.

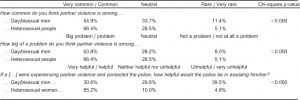

We summarize respondents’ perceptions of IPV for both gay/bisexual men and heterosexual women and the results of chi-square testing in Table 2. Overall, all 3 IPV perceptions differed significantly (p < 0.000). More respondents indicated that IPV was very common or common among heterosexual women than among gay/bisexual men; however, a minority of respondents (11.4%) indicated that IPV among gay/bisexual men was rare or very rare. Similarly, while IPV among heterosexual people was more commonly endorsed as a big problem or a problem compared to IPV among gay/bisexual men (66.4% and 63.8%, respectively), few respondents viewed IPV as not a problem or not at all a problem in either community (5.1% and 8.0%, respectively). However, opinions regarding the helpfulness of a hypothetical police response ranged greatly. While more than 8 in 10 respondents (85.2%) indicated that police would be helpful or very helpful to a woman experiencing partner violence, only 3 in 10 respondents (30.6%) endorsed this opinion for a gay/bisexual man experiencing partner violence. Moreover, 39.5% of respondents indicated that contacting the police would be actually unhelpful or very unhelpful for a gay/bisexual man experiencing partner violence, compared to only 4.8% of respondents who indicated this would be the case for a heterosexual woman who contacted the police.

When comparing perceptions of partner violence among heterosexual women versus among gay/bisexual men, the majority of respondents reported identical perceptions of the commonality of IPV (82.5%) and the magnitude of the IPV problem (84.3%) (Table 3). However, perceptions of police helpfulness showed significant heterogeneity. Only 39.7% of respondents reported identical perceptions of police helpfulness when comparing gay/bisexual men and heterosexual women. Of this majority with divergent perceptions, 97.0%reported that contacting the police would be less helpful for a gay/bisexual men experiencing partner violence compared to a heterosexual woman experiencing partner violence. Therefore, 59.1% of the sample in total viewed the police as less helpful towards gay/bisexual men than heterosexual women in cases of IPV.

We treated this comparatively pessimistic view of a potential police response as the outcome in bivariate analyses (Table 4).With the exception of HIV status, the outcome varied significantly by all exposures, with older men (p < 0.017), white non-Hispanic men (p < 0.000), employed men (p < 0.000), gay/homosexual men (p < 0.000), and men with increasing levels of education (p < 0.000) more commonly holding the comparatively negative view of police response. Perceptions of police helpfulness did not vary significantly by recent receipt of emotional, physical, or sexual IPV. Experiences of homophobia had mixed effects: compared to their counterparts, men who viewed the police as less helpful to gay/bisexual men experiencing partner violence had significantly lower mean scores on the internalized homophobia index (17.4 versus 20.8 respectively, p > 0.000) and significantly higher scores on the homophobic discrimination index (6.0 versus 5.2 respectively, p < 0.000).

The results of the logistic regression modeling are summarized in Table 5. Black/African-American non-Hispanic men had significantly lower odds of holding the comparatively pessimistic view of police response compared to white non-Hispanic men (odds ratio[OR]: 0.73, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.53, 0.99). A dose-response effect was apparent in that increasing education level was correlated to increasing odds of reporting cynicism to police response. In other words, men who had completed a 4-year college/university degree had odds of perceiving that police would be more helpful to a heterosexual female victim of IPV than to a homosexual/bisexual male victim of IPV that were 2.5 times those of men without a high school diploma. A similar finding was documented among men who reported experiencing more forms of homophobic discrimination over their lifetimes. Men with increasing scores on the homophobic discrimination had accordingly higher odds of harboring the negative opinion of possible police response to a homosexual male victim of IPV (OR: 1.11, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.17). Similar to the bivariate analyses, respondents with increasing scores on the internalized homophobia index had significantly lower odds of having the comparatively cynical view of police helpfulness, but this decrease was only approximately 1–2% (OR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.98, 1.00, p>0.033).

![Table 5. Logistic regression results with odds ratios and (95% confidence intervals [CI]). Regression outcome was reporting that police would be less helpful towards a gay/bisexual man experiencing IPV than towards a heterosexual woman experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV). * Significant differences Table 5. Logistic regression results with odds ratios and (95% confidence intervals [CI]). Regression outcome was reporting that police would be less helpful towards a gay/bisexual man experiencing IPV than towards a heterosexual woman experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV). * Significant differences](https://westjem.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/i1936-900X-14-4-354-t05-195x300.jpg)

DISCUSSION

Several conclusions can be drawn from these novel results. First, although it is only recently that same-sex IPV has become the purview of researchers and public health interventionists, gay and bisexual men perceive the severity of partner violence in their community to be on par with the severity of partner violence in the heterosexual community. This finding can be contrasted to findings by McLaughlin and Rozee35 who found that among lesbians, IPV was viewed as more common in different-sex relationships than in same-sex relationships. As all abusive male same-sex relationships involve an abusive male partner, and the culturally dominant image of partner abuse in heterosexual relationship portrays the male as the exclusive perpetrator of violence, gay/bisexual men make comparisons between male-female IPV and male-male IPV more readily. Alternatively, emerging evidence indicates that certain forms of IPV may be more prevalent in male same-sex relationships versus female same-sex relationships; respondents in this sample may have been reflecting their own personal knowledge of IPV in their communities when making these comparisons.36

While gay/bisexual men agree upon the commonness and severity of partner violence, their perceptions of police helpfulness in response to male-male partner violence are negative overall. This result, combined with the finding that men who reported more instances of homophobic discrimination also viewed a hypothetical police response to a gay/bisexual male victim of partner violence as poorer than that for a heterosexual female victim of violence, suggest an understanding of gay men’s perceptions of partner violence within their community that is in line with Meyer’s theory of minority stress.27,28Specifically, gay men’s learned expectations of stigma, prejudice, and rejection are likely being fueled by both a heteronormative society that views homosexuality as deviant and a hegemonic understanding that women, not men, are victims of partner violence. As these stressors are internalized by gay and bisexual men (and compounded by the additional shame felt by victims of partner violence for having experienced partner violence), this homophobia fatigue serves only to further isolate IPV victims in the “double closet” described by Kaschak.37

Another novel finding is that recent experience of IPV was not correlated to a negative perception of police helpfulness in the multivariate analysis. From the data, it is unknown whether or not persons who recently experienced partner violence did or did not contact the police; thus, it may be the case that persons experiencing IPV who did contact the police received help from them upon contact. Alternatively, if a respondent experiencing IPV contacted the police and was unaided by them, he may have applied this cynicism to both hypothetical situations presented (and therefore would not have been classified as having a disparate view). Furthermore, while 27.6% (n=273) of respondents were classified as having recently experienced IPV per the R-CTS, 36.3% of these respondents (n=99) reported experiencing only emotional/psychological IPV. Previous research with women has shown that, for a variety of reasons, persons experiencing non-physical, non-sexual IPV are less likely to contact the police than persons experiencing physical and/or sexual partner violence.10,14,38 Additionally, same-sex abusive behavior has been shown (among lesbian women) to not be readily recognized as constituting IPV, another factor that would impact the process of deciding to contact the police.35

Indeed, minority stress (and in particular expectations of stigma and rejection) can be applied to Liang et al’s39 framework for help-seeking processes among survivors of IPV. First, the male victim of male-male IPV may delay recognizing and defining that IPV is a problem in his relationship due to cultural messaging that portrays the heterosexual woman as the victim of IPV (to the exclusion of the gay/bisexual man). Second, he may delay deciding to contact the police for assistance due to his learned anticipation of homophobic stigma and rejection, as such an anticipation may lead him to view the police as less legitimate entity. This lack of legitimacy, fueled by anticipation of homophobia, is supported by empirical findings in the literature. Seelau et al40 demonstrated that while the victim’s sex, rather than his sexual orientation, modifies an observer’s perception of the severity of an episode of partner violence, IPV episodes are viewed as less severe and less warranting of intervention when the victim of the violence is male. Implicit in this gendered understanding of partner violence is the idea that men (and not women) should be able to defend themselves against an attacker.41,42 Finally, minority stress may impact the gay/bisexual male IPV victim’s selection of support. Men who anticipate – and, indeed, may have experienced – homophobic stigma and rejection from police officers (an anticipation that is not entirely unfounded in the wake of the Atlanta Police Department’s 2009 warrantless, illegal raid of the Atlanta Eagle), may seek alternative sources of support, such as friends and family, in lieu of legal support.43

LIMITATIONS

The findings of this study are limited by its design. We used venue-based sampling (VBS) to recruit participants, and, while VBS has been shown to generate samples that are similar to more classically rigorous recruitment methodologies, VBS necessarily excludes potential study participants who do not access venues during the sampling frame. The reported IPV prevalence is likely underestimated; although the survey was anonymous, respondents may have nonetheless been reluctant to report being criminally victimized by their partners. As was discussed previously, the survey instrument did not assess whether or not survivors of IPV did or did not actually contact the police for assistance, so the actual effectiveness of police intervention in cases of male same-sex IPV (or in any cases of IPV) is not here considered.

CONCLUSION

For all survivors of IPV, the ability to access police assistance is imperative. The actual helpfulness of a police response to a homosexual male victim of IPV is of secondary concern: if he never seeks police intervention for anticipation of futility and/or fear of rejection, whatever assistance the police would have been able to provide him will not reach him. The results of this study demonstrate that efforts must be made to improve both the supply of police assistance (i.e., its quality and effectiveness) and gay/bisexual men’s demand for this assistance (i.e., their perceptions of its quality and effectiveness, in order words, police legitimacy). While efforts can be made to improve the training that police officers receive in terms of how to respond to situations of partner violence, police forces should attempt to increase their legitimacy by communicating to the LGBT community that their reports of partner violence will be taken seriously – and, internally, police forces must ensure that policies are in place that ensure that those reports will indeed be taken seriously. Community groups that provide support to LGBT persons experiencing partner violence can liaise with the domestic violence corps of their local police forces in order to provide this sensitivity training. As data are lacking, future research should analyze outcomes for gay/bisexual IPV survivors who do enlist police support in comparison to female IPV survivors who also access police support. From a policy perspective, lawmakers should ensure that the extra legal protections afforded to survivors of IPV, such as protective orders, are available to persons experiencing IPV, regardless of gender or sexual orientation. A way to achieve this end is to extend legal recognition of same-sex partnerships – the right to marriage – to all same-sex couples who desire it. Emergent evidence already indicates that legal recognition of same-sex partnerships via marriage is correlated with decreased mental distress, including decreased internalized homophobia.44,45 Extending the legal recognition of marriage to same-sex couples may have the added benefit of having law enforcement officials increasingly appreciate the legitimacy of same-sex partnerships (and therefore the legitimacy of any possible violence that may occur during those partnerships), and will ensure that law enforcement is able to protect all IPV survivors equally under the law. As the response to same-sex IPV emerges in courthouses, police stations, hospitals, clinics, and community centers, the homophobia fatigue documented here among gay and bisexual men must be considered by practitioners not only as a potential barrier to success, but also as an opportunity for dialogue, modified efforts, and collaboration.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Monica H. Swahn, PhD, MPH

Submission history: Submitted December 14, 2012; Revision received February 18, 2013; Accepted February 26, 2013

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

DOI: 10.5811/westjem.2013.3.15639

Address for Correspondence: Catherine Finneran, MPH. 1518 Clifton Rd NE, Atlanta, GA 30312. Email: cafinne@emory.edu.

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. This original research was supported by funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, grant #5R21HD066306-02, and the Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI050409). The authors disclosed no other potential sources of bias.

REFERENCES

1. Tjaden P, Thoennes N, Allison CJ. Comparing violence over the life span in samples of same-sex and opposite-sex cohabitants. Violence Vict. 1999;14(4):413–425. [PubMed]

2. Blosnich JR, Bossarte RM. Comparisons of Intimate partner violence among partners in same-sex and opposite-sex relationships in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(12):2182.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

3. Messinger AM. Invisible Victims: Same-Sex IPV in the national violence against women survey. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26(11):2228. [PubMed]

4. Nieves-Rosa LE, Carballo-Diéguez A, Dolezal C. Domestic abuse and HIV-risk behavior in Latin American men who have sex with men in New York city. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2000;11(1):77–90.

5. Balsam KF, Lehavot K, Beadnell B. Sexual revictimization and mental health: a comparison of lesbians, gay men, and heterosexual women. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26(9):1798. [PubMed]

6. Pantalone DW, Hessler DM, Simoni JM. Mental health pathways from interpersonal violence to health-related outcomes in HIV-positive sexual minority men. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(3):387.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

7. Finneran C, Stephenson R. Intimate partner violence among men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2013;14(2):168–185. [PubMed]

8. Relf M. Battering and HIV in men who have sex with men: a critique and synthesis of the literature.J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2001;12(3):41–48. [PubMed]

9. Felson RB, Messner SF, Hoskin AW. et al. Reasons for reporting and not reporting domestic violence to the police. Criminol. 2002;40(3):617–648.

10. Coulter ML, Kuehnle K, Byers R. et al. Police-reporting behavior and victim-police interactions as described by women in a domestic violence shelter. J Interpers Violence. 1999;14(12):1290–1298.

11. Hilton NZ, Harris GT. Predicting Wife Assault A Critical Review and Implications for Policy and Practice. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2005;6(1):3–23. [PubMed]

12. Berk RA, Campbell A, Klap R. et al. The deterrent effect of arrest in incidents of domestic violence: A Bayesian analysis of four field experiments. Am Sociol Review. 1992;57(5):698–708.

13. Mears DP, Carlson MJ, Holden GW. et al. Reducing Domestic Violence Revictimization The Effects of Individual and Contextual Factors and Type of Legal Intervention. J Interpers Violence.2001;16(12):1260–1283.

14. Wolf ME, Ly U, Hobart MA. et al. Barriers to seeking police help for intimate partner violence. J Family Violence. 2003;18(2):121–129. p.

15. Singer SI. The fear of reprisal and the failure of victims to report a personal crime. Journal of Quantitative Criminol. 1988;4(3):289–302.

16. Hutchison IW, Hirschel JD. Abused women help-seeking strategies and police utilization. Violence Against Women. 1998;4(4):436–456.

17. Hamilton B, Coates J. Perceived helpfulness and use of professional services by abused women. J Fam Violence. 1993;8(4):313–324.

18. Fugate M, Landis L, Riordan K. et al. Barriers to domestic violence help seeking implications for intervention. Violence Against Women. 2005;11(3):290–310. [PubMed]

19. Bennett L, Goodman L, Dutton MA. Systemic obstacles to the criminal prosecution of a battering partner a victim perspective. J Interpers Violence. 1999;14(7):761–772.

20. Fleury RE. Missing Voices Patterns of Battered Women’s Satisfaction With the Criminal Legal System. Violence Against Women. 2002;8(2):181–205.

21. Stephens BJ, Sinden PG. Victims’ voices domestic assault victims’ perceptions of police demeanor. J Interpers Violence. 2000;15(5):534–547.

22. Hickman LJ, Simpson SS. Fair treatment or preferred outcome? The impact of police behavior on victim reports of domestic violence incidents. Law & Society Review. 2003;37(3):607–634.

23. Tyler TR. Enhancing police legitimacy. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci. 2004;593(1):84–99.

24. Tyler TR, Huo YJ. Trust in the law: Encouraging public cooperation with the police and courts. Vol. 5. Russell Sage Foundation Publications. 2002.

25. Mazerolle L, Bennett S, Sargeant E. Legitimacy in policing: a systematic review. Campbell Collaboration. 2012.

26. Hinds L, Murphy K. Public satisfaction with police: using procedural justice to improve police legitimacy. Aust N Z J Criminol. 2007;40(1):27–42.

27. Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):38–56.[PubMed]

28. Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

29. Muhib FB, Lin LS, Stueve A. et al. A venue-based method for sampling hard-to-reach populations.Public Health Reports. 2001;116(1):216. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

30. Brady S, Busse W. The gay identity questionnaire: a brief measure of homosexualIy identity formation. J Homosex. 1994;26(4):1–22. [PubMed]

31. Díaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E. et al. The impact on homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: findings from 3 US cities. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(6):927–932. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

32. Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S. et al. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2) J Fam Issues. 1996;17(3):283–316.

33. Straus MA, Douglas EM. A short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence Vict. 2004;19(5):507–520. [PubMed]

34. Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The conflict tactics (CT) scales. J Marriage Fam. 1979:75–88.

35. McLaughlin EM, Rozee PD. Knowledge about heterosexual versus lesbian battering among lesbians.Women Therapy. 2001;23(3):39–58.

36. Blosnich JR, Bossarte RM. Comparisons of intimate partner violence among partners in same-sex and opposite-sex relationships in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(12):2182–2184.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

37. Kaschak E. Intimate Betrayal. Women Therapy. 2001;23(3):1–5.

38. Bonomi AE, Holt VL, Martin DP. et al. Severity of intimate partner violence and occurrence and frequency of police calls. J Interpers Violence. 2006;21(10):1354–1364. [PubMed]

39. Liang B, Goodman L, Tummala-Narra P. et al. A theoretical framework for understanding help-seeking processes among survivors of intimate partner violence. Am J Community Psychol.2005;36(1):71–84. [PubMed]

40. Seelau E, Seelau S, Poorman P. Gender and role-based perceptions of domestic abuse: does sexual orientation matter? Behav Sci Law. 2003;21(2):199–214. [PubMed]

41. Hollander JA. Vulnerability and dangerousness: the construction of gender through conversation about violence. Gender Society. 2001;15(1):83–109.

42. Malamuth NM, Linz D, Heavey CL. et al. Using the confluence model of sexual aggression to predict men’s conflict with women: a 10-year follow-up study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(2):353. [PubMed]

43. Bagby D, Douglas-Brown L. Breaking: Atlanta City Council approves settlement over Atlanta Eagle gay bar raid. The GA Voice. 2010. Available at: http://www.thegavoice.com/index.php/news/atlanta-news-menu/1657-breaking-atlanta-city-council-approves-settlement-over-atlanta-eagle-gay-bar-raid.

44. Riggle EDB, Rostosky SS, Horne SG. Psychological distress, well-being, and legal recognition in same-sex couple relationships. J Fam Psychol. 2010;24(1):82–86. [PubMed]

45. Wight RG, LeBlanc AJ, Badgett L. Same-sex legal marriage and psychological well-being: findings from the California health interview survey. Am J Public Health. 2012 [PMC free article] [PubMed]