| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Rob Stephenson, PhD | Rollins School of Public Health, Hubert Department of Global Health, Atlanta, Georgia |

| Kimi N. Sato, MPH | Rollins School of Public Health, Hubert Department of Global Health, Atlanta, Georgia |

| Catherine Finneran, MPH | Rollins School of Public Health, Hubert Department of Global Health, Atlanta, Georgia |

Introduction Methods Results Discussion Conclusion

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Despite a recent focus on intimate partner violence (IPV) among men who have sex with men (MSM), the male-male couple is largely absent from the IPV literature. Specifically, research on dyadic factors shaping IPV in male-male couples is lacking.

Methods: We took a subsample of 403 gay/bisexual men with main partners from a 2011 survey of approximately 1,000 gay and bisexual men from Atlanta. Logistic regression models of recent (<12 month) experience and perpetration of physical and sexual IPV examined dyadic factors, including racial differences, age differences, and social network characteristics of couples as key covariates shaping the reporting of IPV.

Results: Findings indicate that men were more likely to report perpetration of physical violence if they were a different race to their main partner, whereas main partner age was associated with decreased reporting of physical violence. Having social networks that contained more gay friends was associated with significant reductions in the reporting of IPV, whereas having social networks comprised of sex partners or closeted gay friends was associated with increased reporting of IPV victimization and perpetration.

Conclusion: The results point to several unique factors shaping the reporting of IPV within male-male couples and highlight the need for intervention efforts and prevention programs that focus on male couples, a group largely absent from both research and prevention efforts.

INTRODUCTION

Programmatic efforts and research studies of intimate partner violence (IPV) have long focused on female victim – male perpetrator models, almost to the exclusion of both male victims and IPV within same-sex relationships. Recently, studies have begun to look at intimate partner violence (IPV) among men who have sex with men (MSM): MSM refers to the behavior of same-sex male sexual behavior, and is not linked to a sexual identity such as gay or bisexual. Studies of IPV among MSM have found both a similarly high prevalence to that observed among heterosexual women, and that IPV among MSM occurs at significantly higher rates in comparison to heterosexual men.1,2 Studies focusing specifically on gay and bisexual men have found that approximately 25–50% of gay and bisexual men in the U.S. report experiencing physical IPV, while 12–52% report experiencing sexual IPV.1,3–5 Tjaden et al,4 showed that 21.5% of men reporting a history of cohabitation with a same-sex partner reported experiencing physical abuse in their lifetimes in comparison to 7.1% of men with a history of opposite-sex cohabitation. There is evidence that MSM – and gay/bisexual men – are especially at risk for IPV over their lifetimes, and that the risks of experiencing IPV are higher among MSM of color, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive men, and MSM with lower levels of education.6–10 Several studies have also found associations between IPV and sexual risk-taking and increased risk of HIV acquisition among MSM.9,11 Many studies have examined how dyadic characteristics of heterosexual couples shape the risk of IPV and how the risk of IPV is influenced by patterns of social support. Despite the comparably high rates of IPV in male-male couples (which may consist of combinations of MSM and gay and bisexual men), there is a dearth of studies that have examined how partner and dyadic characteristics and the social network characteristics of the individual shape the experience of IPV among male-male couples.12–14

The existing evidence suggests that IPV affects approximately one quarter to one half of all same-sex relationships.15–18 The National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs reported 6,523 cases of IPV in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) relationships in 2003, with most cases (83%) occurring in gay and lesbian relationships.19 Physical abuse seems to occur in a significant portion of abusive same-sex relationships. Elliot20 and De Vidas21 suggest that between 22–46% of lesbians have been in relationships in which physical violence has occurred. McClennen et al,22 using a sample of 63 gay men, found that participants were often physically struck by their partners, while Greenwood et al6reported that 22% of a sample of MSM had been subjected to physical abuse from an intimate partner. Research also indicates that sexual abuse is common in IPV-afflicted same-sex relationships. Walder-Haugrud and Gratch5 reported that 52% of their sample of gay men experienced one or more incidents of sexual abuse. Similarly, Toro-Alfonso and Rodriques-Madera23 found that approximately 25%of a sample of Puerto Rican gay males had experienced sexual coercion. Clearly, a large number of same-sex relationships experience IPV, and the levels experienced appear to be similar, if not higher, than those seen in heterosexual couples.20

Capaldi et al24 conducted a systematic review of 228 IPV-focused research articles and found that social support characteristics and the behaviors and characteristics of main partners were a strong influence on the experience of IPV. However, none of the studies that focused exclusively on same-sex couples met the criteria for inclusion in the systematic review, due primarily to small sample sizes, and only 2 of the studies included in the review had samples that contained both heterosexual and same-sex relationships, pointing to the lack of research examining dyadic or social support influences on IPV among same-sex couples.25,26 In terms of dyadic influences on IPV, among heterosexual populations a number of studies suggest that the experience of IPV decreases as the age of the partner increases, while others have shown that education and income, in particular dyadic differences in education and income, are significantly associated with the risk of IPV among heterosexual couples.27–29 Additionally, economic stress has been shown to be a major risk factor for IPV among heterosexual couples: in a cross-sectional study of men and women in the U.S. Air Force, researchers found that financial stress was a significant predictor of both men’s and women’s perpetration of IPV.30 Main partners who were exposed to violence as a child, either witnessing parental IPV or experiencing early childhood abuse, have also been shown to report higher levels of violence in their relationships.31 Although these findings suggest that partner characteristics play an important role in the experience of IPV among heterosexual couples, information on what these characteristics look like in male-male couples is lacking. Furthermore, the majority of the research on partner characteristics involves individual-level data rather than couple-level data, thus largely ignoring how differences in dyadic characteristics (e.g. age or educational differences) may influence the risk of IPV.

Several studies have shown that social isolation or lack of social support is a significant risk factor for experience and perpetration of IPV among heterosexual populations.25,32,33 Lanier and Maume found that women in rural and urban areas of the U.S. with greater levels of social support and social interaction were less likely to experience IPV.32 Similarly, Van Wyk et al33 found that women living in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods and those receiving less social support were at a greater risk of IPV. For MSM, or gay and bisexual men, social networks may influence the risk of IPV through the provision of social support, increasing access to services and resources, by providing access to role models in the forms of successful relationships, and through the provision of social acceptance through normalizing the presence of same-sex couples in a heterosexually-dominated society.34–36 However, research on social networks and social support among MSM has focused almost exclusively on the influence of social networks in shaping sexual risk taking and risk of HIV, and we find no studies that have examined how social support or social networks shape the risk of IPV among male-male couples.37,38

The majority of studies of IPV among MSM have focused on prevalence and individual-level risk factors for IPV.17–23 To date, research has largely ignored the role of dyadic characteristics in shaping the risk of IPV among male couples, and has overlooked how the risk of IPV may be shaped by the size and composition of an individual’s social network. In this study, we examine how dyadic characteristics, dyadic differences and the size and composition of social networks influence the reporting of recent physical and sexual IPV among a sample of 403 gay and bisexual men with main partners in Atlanta, Georgia. This new information has the potential to inform the development of culturally appropriate interventions tailored to the unique contexts of male-male couples, a population largely overlooked in current research and prevention efforts.

METHODS

Emory University’s institutional review board approved this study. Between September–December 2011, participants were recruited into the study using venue-based sampling. Venue-based sampling is a derivative of time-space sampling, in which sampling occurs within prescribed blocks of time at particular venues. As a method to access hard-to-reach population, venue-based recruitment is a process in which a sampling frame of venue-time units is created through formative research with key informants and community members. After creating a list of potential venues where the target population is reported to be more prevalent than in the general community, researchers visit each venue at the times it is reported to be active (for example, Thursdays from 9PM–1AM) to confirm that the venue is active at those times and the population in question accesses the venue; this venue-time unit is then added to the sampling frame. In order to reach a diverse population of gay and bisexual men in the Atlanta area, the venue sampling frame used for this study consisted of a wide variety of gay-themed or gay-friendly venues, including Gay Pride events, gay sports teams events, gay fundraising events, downtown areas, gay bars, bathhouses, and an AIDS service organization. All venues were within the Atlanta Metropolitan area. The sampling frame used in this study contained over 160 venue-time units, and was updated monthly as venues closed or as new venues became available. A randomized computer program assigned venue-time units monthly, with at least one recruitment event per day.

During recruitment, 2 or more study recruiters wearing study t-shirts stood adjacent to the venue during the time period prescribed by the computer program. Recruiters then drew an imaginary line on the ground and then approached every nth man who crossed it; n varied between 1 and 3 depending on the volume of traffic at the venue. After introducing him/herself, the recruiter would ask if the man was interested in seeing if he was eligible for a research study. If he agreed to be screened, he was then asked a series of 8 questions to assess his eligibility, including his sexual orientation, recent sex with a man, race, age, and residence in the Atlanta Metro Area. Responses for all persons were recorded on palm-held computers, including whether or not a person agreed to be screened for eligibility. Eligible men were then read a short script that described the study process: a web-based survey approximately 20 minutes in length that could be completed at home, or, in the case of 5 venues (the AIDS service organization, the drop-in center, Atlanta Pride, In the Life Pride, and a National Coming Out Day event), at the venue itself on a tablet computer. Men interested in study participation were then given a card with a web address and a unique identifier that would link their recruitment data to their survey data. Participants who completed the survey at the venue were compensated with a gift card; participants who completed the survey at home were compensated with the same value of gift card sent to them electronically.

The self-administered, web-based survey contained several domains of questions regarding demographics, recent sexual behavior with male partners, intimate partner violence (IPV), couples’ coping and communication, social network characteristics, and minority stress (e.g., internalized homophobia). Of 4,903 men approached, 2,936 (59.9%) agreed to be screened for the study. Of these, 2,093 (71.3%) were eligible for study participation. Men were eligible for study participation if they reported being 18 years of age or older, being male, identifying as gay/homosexual or bisexual, living in the Atlanta Metropolitan Area, and having had sex with a man in the previous 6 months. Of eligible participants, 1,965 (93.9%) were interested in study participation. A total of 1,075 men completed the survey; thus 21.9% of men approached and 51.4% of eligible men completed the survey. Approximately one third (33.7%) completed the survey at a venue, while the remaining two thirds (66.3%) of respondents completed the survey at home. Of the 1,075 men who completed the survey, approximately half (49.3%) reported having a main partner (“Are you currently in a relationship with a male partner? Is this male partner someone who you feel committed to above all others? You might call this person a boyfriend, life partner, husband, or significant other.”). Of the men who responded that they had a main partner, 403 had complete data for all covariates of interest and were included in the final analysis sample (Table 1).

Survey participants were assessed for recent intimate partner violence from a male partner, either physical (“In the last 12 months, have any of your partners ever tried to hurt you? This includes pushing you, holding you down, hitting you with a fist, kicking you, attempting to strangle you, and/or attacking you with a knife, gun or other weapon”) or sexual (“In the last 12 months, have any of your partners ever used physical force or verbal threats to force you to have sex when you did not want to?”).We used the same questions to measure perpetration of IPV in the last 12 months. The analysis examines 4 outcomes, each of them self-reported: experience of physical violence, experience of sexual violence, perpetration of physical violence, and perpetration of sexual violence in the 12-month period prior to the survey. We grouped covariates of interest into 3 categories: dyadic differences, main partner characteristics, and social network characteristics. The dyadic differences consisted of differences in race, education, differences in sexual orientation, and the age difference between the main partner and the participant. The main partner characteristics consisted of covariates related to the participant’s main partner including race, age, and their sexual orientation.

To capture data on social networks, we asked respondents about up to 5 of their closest friends, who were classified as “people that you talk to at least once a month.” Respondents were asked to provide the age, gender, perceived sexual orientation, whether their friend was out to others if they were gay or bisexual, and relationship status of each of the friends they listed. To measure the age difference within the network of friends, the average age of the network was subtracted from the respondent’s age and then categorized into 4 categories based on the distribution of the quartiles: 3.4–2 years older, 3.25–0.2 years older, 0–3 years younger, and 3.2 years or more younger than the respondent. The analysis also considered the proportion of the respondent’s network that was comprised of gay friends, gay friends in relationships, closeted gay friends, out gay friends, straight friends in relationships, and sexual partners. The analysis also considered the number of friends with the same race as the respondent. For individual characteristics, the analysis considered education, employment, age (continuous variable), race (white, black/African American, or Latino/other), sexual orientation (homosexual/gay or bisexual) and HIV status (positive, negative or unknown/ never been tested).

We analyzed the data using STATA 12. Using a backwards stepwise procedure, we created 4 separate logistic regression models for the 4 outcomes of interest. In each model, we included individual characteristics, dyadic differences, main partner characteristics and social network characteristics.

RESULTS

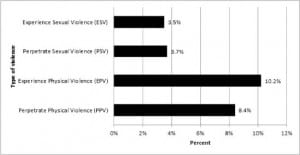

The sample of 403 participants reflected a diverse sample with 59.8% white non-Hispanic, 25.6% black/African-American, and 14.6% Latino/other. In addition, 54.8% reported having a college education or more, 29.0% reported some college or a two-year degree, and 16.1% reported a high school education or less. The mean age was 36.1 years (18–71years) with the majority reporting homosexual/gay sexual orientation (93.6%), negative HIV status (72.7%), and current employment (83.7%). Reporting of physical IPV was higher than sexual IPV: 10.2% of respondents reported experiencing physical IPV in the last 12 months, while 4.8% reported perpetrating physical IPV. Fewer participants reported experiencing (3.7%) or perpetrating (3.5%) sexual IPV (Figure).

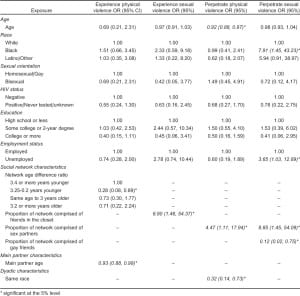

The results of the logistic models are shown in Table 2. Of the demographic variables, only age, race and employment status were found to be associated with 2 of the 4 outcomes. Older men were significantly less likely to report perpetration of physical violence (odds ratio [OR]: 0.92, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.88, 0.97). Black/African American men were 7.91 times (95% CI: 1.45, 43.23) more likely to report perpetration of sexual violence when compared to white men. Unemployed men had significantly higher odds of reporting recent perpetration of sexual violence (OR 3.65, 95% CI: 1.03, 12.89) than employed men.

Of the dyadic factors, men who were the same race as their main partner had significantly lower odds of reporting perpetration of physical violence towards their partner in the past year compared to men in inter-racial dyads (OR 0.32 95% CI: 0.14, 0.73). Of the main partner characteristics, only the main partner’s age was found to be associated with experience of physical violence: men with older main partners were significantly less likely to report experiencing physical IPV.

Several social network factors were significantly associated with IPV. The greater the proportion of their network that was comprised of closeted gay friends, the more likely they were to report experience of sexual violence (OR: 8.90, 95% CI: 1.46, 54.37). Conversely, the greater the proportion of their network that was comprised of openly gay friends, the less likely they were to report perpetration of sexual violence (OR: 0.12, 95% CI: 0.02, 0.75). Men whose social networks had a high proportion of sex partners were more likely to report perpetration of physical violence (OR: 4.47, 95% CI: 1.11, 17.94) and sexual violence (OR: 8.85, 95% CI: 1.45, 54.09). Respondents whose social network was on average slightly younger than them (0.2–3.25 years) were significantly less likely to report experiencing physical IPV (OR: 0.28 95% CI 0.08, 0.89).

DISCUSSION

Studies of IPV among gay and bisexual men are relatively new, at least relative to the wealth of studies on male-female IPV, and previous studies have shown rates of male-to-male IPV ranging between 11% and 44%.39 The results presented here show slightly lower levels of physical IPV than have been shown in some previous studies, yet show relatively high levels of reporting of the experience of and perpetration of sexual IPV: interestingly, similar percentages of participants reported experience or perpetration of sexual IPV. The present analyses are unique in their focus on IPV among male-male dyads (which may include both MSM and gay and bisexual men), and the inclusion of covariates beyond the individual level to include dyadic differences, partner characteristics, and social network size and composition.

The factors that were significantly associated with the reporting of IPV among male-male couples highlight the potential role of minority stress in shaping the risk of experience or perpetration of violence among male-male couples. Respondents who identified as a racial minority (black/African American) or experienced financial stress (unemployed men) were more likely to report increased perpetration of sexual IPV. Lower levels of income may be reflective of a lack of access to social capital and resources, creating an economic stress that manifests as perpetration of or vulnerability to IPV. Men who identify as a racial minority may face stress through exposure to racism, both in the LGBT community and beyond, or through increased levels of homophobia known to exist in communities of color in the U.S.44,45 However, the sample for this study was predominantly white, with too few numbers in each of the ethnic and racial groups to allow a deeper investigation other than white versus other of the racial differences in IPV among participants (as noted by the large confidence intervals around estimate for black/African American men).

At the dyadic level, being in an inter-racial dyad was associated with increased levels of perpetration of physical IPV. Again, the suggested causal pathway lies in the stress that may be placed on the relationship due to either perceived or experienced racism or homophobia in the LGBT community or communities of color. Related to the main partner characteristics, the main partner’s age was found to be significantly associated with a reduction in experiencing physical IPV. This finding is similar to studies of heterosexual couples, where violence decreases as the main partner’s age increases.27,28

The majority of the research on the social networks of gay and bisexual men has focused on how social networks influence sexual risk-taking behaviors.34–36 The results of this study suggest a role for minority stress in explaining how social networks shape the risk of IPV within male-male couples. Men with more closeted gay friends in their network were more likely to experience sexual violence, and men with more sex partners in their network were more likely to perpetrate physical and sexual violence. The latter result is similar to other studies that have linked perpetration of violence to a greater number of sexual partners among heterosexual individuals.40,41 Both of these results could be interpreted as minority stress: men whose social networks are primarily composed of closeted gay men may have less access to the wider LGBT community, and as such may have lower access to positive LGBT role models, social support and culturally appropriate services. Additionally, these men may themselves be experiencing difficulties in disclosing their own sexual orientation, and this stress may manifest as IPV in relationships. Men whose social networks are largely composed of sex partners may have fewer opportunities to create positive social bonds and interactions, they may be less socially visible in the LGBT community, may have fewer positive LGBT role models, or may themselves be struggling with issues around their sexual orientation, all of which may reduce their access to information and resources in the LGBT community. However, it is possible that the experience of IPV may act as a barrier to involvement or participation in social aspects of the LGBT community. Surprisingly, men whose network was slightly younger than them were less likely to experience physical IPV, perhaps suggesting that access to peers acts as a source of information and resources. Further research is needed to understand the causal mechanisms between these social network measures and IPV. However, men with more gay friends in their network were less likely to perpetrate sexual IPV, further suggesting that access to the LGBT community, social support and resources may reduce the stressors that lead to IPV within male-male couples.

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations to the current study. We used venue-based sampling to recruit the participants instead of random sampling; however, previous studies have demonstrated that this form of sampling results in a sample of similar diversity as is found when using random sampling methods, and is a useful tool for sampling hard-to-reach populations – such as gay/bisexual men – for whom no pre-existing sample frame is available.42 The small sample size and possible selection bias in both the decision to complete the questionnaire and the decision to answer the questions on IPV are also limitations. Kaschak49 refers to the “double closet” that surrounds IPV in same-sex relationships; the dual burden of shame and silence surrounding both the discussion of IPVand the discussion of sexuality; hence, it is possible that IPV may be under-reported. Although a recent recall period (one-year) was used to measure both experience of IPV and receipt of IPV, the variables used to measure IPV may have captured IPV that occurred outside of the respondent’s current main partnership. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of the data means that only associations between dyadic characteristics and the reporting of IPV can be drawn; there are no causal relationships identified here. Further work, using longitudinal data, is required to further understand the relationships between dyadic and social network characteristics and IPV among gay and bisexual men.

CONCLUSION

The results highlight that there are influences on IPV within male-male couples that stretch beyond the commonly examined individual characteristics to include the characteristics of the partner, the differences in characteristics between partners, and the social networks within which individuals socialize. Clearly examining individual risk factors alone is not sufficient in addressing IPV among gay and bisexual men; this has already been shown for studies of IPV among heterosexual populations. There is clearly a need for further research into issues surrounding IPV in same-sex male relationships, which are vulnerable to high levels of IPV, and to understand the complex relationships that exist between IPV, dyadic characteristics and social networks. Many of the results point to the role of minority stress in shaping the risk of IPV in male-male couples. Future areas of research and intervention should focus on how structural stressors, such as racism, homophobia and heteronormativity, may manifest as IPV in same-sex dyads. Such information is vital for the development of effective interventions to reduce violence and improve health among gay and bisexual men in the U.S.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Abigail Hankin, MD, MPH

Submission history: Submitted December 12, 2012; Revision received February 18, 2013; Accepted February 21, 2013

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

DOI: 10.5811/westjem.2013.2.15623

Address for Correspondence: Rob Stephenson, PhD. Hubert Department of Global Health, Rollins School of Public Health, 1518 Clifton Road, NE, #722, Atlanta, GA 30322. Email: rbsteph@sph.emory.edu.

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. This original research was supported by funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, grant #5R21HD066306-02, and the Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI050409). The authors disclosed no other potential sources of bias.

REFERENCES

1. Blosnich JR, Bossarte RM. Comparisons of intimate partner violence among partners in same-sex and opposite-sex relationships in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:2182–2184.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

2. Messinger AM. Invisible victims: Same-Sex IPV in the national violence against women survey. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26:2228–2243. [PubMed]

3. Balsam KF, Lehavot K, Beadnell B. et al. Childhood abuse and mental health indicators among ethnically diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:459.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

4. Tjaden P, Thoennes N, Allison CJ. Comparing violence over the life span in samples of same-sex and opposite-sex cohabitants. Violence Vict. 1999;14(4):413–425. [PubMed]

5. Waldner-Haugrud LK, Gratch LV, Magruder B. Victimization and perpetration rates of violence in gay and lesbian relationships: Gender issues explored. Violence Vict. 1997;12:173–184. [PubMed]

6. Greenwood GL, Relf MV, Huang B. et al. Battering victimization among a probability-based sample of men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1964–1969. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

7. Houston E, McKirnan DJ. Intimate partner abuse among gay and bisexual men: Risk correlates and health outcomes. J Urban Health. 2007;84:681–690. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

8. Kalichman SC, Simbayi L. Traditional beliefs about the cause of AIDS and AIDS-related stigma in South Africa. AIDS care. 2004;16:572–580. [PubMed]

9. Koblin BA, Husnik MJ, Colfax G. et al. Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. Aids. 2006;20:731–739. [PubMed]

10. Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J. et al. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health.2003;93:939–942. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

11. Welles SL, Corbin TJ, Rich JA. et al. Intimate partner violence among men having sex with men, women, or both: early-life sexual and physical abuse as antecedents. J Community Health.2011;36:477–485. [PubMed]

12. Bradbury TN, Lawrence E. Physical aggression and the longitudinal course of newlywed marriage. In: Arriaga XB, Oskamp S, editors. Violence in intimate relationships. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. pp. 181–202.

13. Capaldi DM, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A life span developmental systems perspective on aggression toward a partner. In: Pinsof WM, Lebow J, editors. Family psychology: The art of the science. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 141–167.

14. O’Leary KD, Smith Slep AMS. A dyadic longitudinal model of adolescent dating aggression. J Clini Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32:314–327. [PubMed]

15. McClennen JC. Domestic violence between same-gender partner recent findings and future research.J Interpers Violence. 2005;20(2):149–154. [PubMed]

16. Burke TW, Jordan ML, Owen SS. A cross-national comparison of gay and lesbian domestic violence.J Contemporary Criminal Justice. 2002;18:231–56.

17. Alexander CJ. Violence in gay and lesbian relationships. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2002;14:95–8.

18. Pitts EL. Domestic violence in gay and lesbian relationships. Gay and Lesbian Med Associa Jl.2000;4:195–6.

19. National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence. Lesbian/gay power and control wheel (adapted from Domestic Abuse Intervention Project, Duluth, MN) National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence. Available at: http://www.ncdsv.org/publication_wheel.html. Accessed November 11, 2012.

20. Elliott P. Shattering illusions: Same-sex domestic violence. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 1996;4:1–8.

21. De Vidas M. Childhood sexual abuse and domestic violence: A support group for Latino gay men and lesbians. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 1999;10:51–68.

22. McClennen JC, Summers B, Vaugh C. Gay men’s domestic violence: dynamics, help-seeking behaviors, and correlates. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2002;14:23–49.

23. Toro-Alfonso J, Rodriguez-Madera S. Sexual coercion in a sample of Puerto Rican gay males. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2004;17:47–58.

24. Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW. et al. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:231–280. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

25. Golinelli D, Longshore D, Wenzel SL. Substance use and intimate partner violence: Clarifying the relevance of women’s use and partners’ use. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2009;36(2):199–211. [PubMed]

26. Moracco KE, Runyan CW, Bowling JM. et al. Women’s experiences with violence: A national study.Womens Health Issues. 2007;17(1):3–12. [PubMed]

27. Rodriguez E, Lasch KE, Chandra P. et al. Family violence, employment status, welfare benefits, and alcohol drinking in the United States: what is the relation? J Epidemiol Community Health.2001;55(3):172–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

28. Kim HK, Laurent HK, Capaldi DM. et al. Men’s aggression toward women: A 10-year panel study. J Marriage Fam. 2008;70:1169–1187. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

29. Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Schafer J. Socioeconomic predictors of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. J Fam Violence. 2002;17:377–389.

30. Smith Slep AMS, Foran HM, Heyman RE. et al. Unique risk and protective factors for partner aggression in a large scale Air Force survey. J Community Health. 2010;35:375–383. [PubMed]

31. Jain S, Buka SL, Subramanian SV. et al. Neighborhood predictors of dating violence victimization and perpetration in young adulthood: A multilevel study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1737–1744.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

32. Lanier C, Maume MO. Intimate partner violence and social isolation across the rural/urban divide.Violence against Women. 2009;15:1311–1330. [PubMed]

33. Van Wyk JA, Benson ML, Fox GL. et al. Detangling individual-, partner-, and community-level correlates of partner violence. Crime & Delinquency. 2003;49:412–438.

34. Brooks VR. Minority stress and lesbian women. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1981.

35. Friedman RC. Couple therapy with gay couples. Psychiatric Annals. 1991;21:485–490.

36. Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J Health Social Behav. 1995;36:38–56.[PubMed]

37. Johnson SB, Frattaroli S, Campbell J. et al. “I Know What Love Means.” Gender-Based Violence in the Lives of Urban Adolescents. J Womens Health. 2005;14:172–179. [PubMed]

38. Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT. et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents. JAMA. 2010;304:527–535. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

39. Herek GM, Sims C. Sexual orientation and violent victimization: Hate crimes and intimate partner violence among gay and bisexual males in the United States. In: Wolitski RJ, Stall R., Valdiserri RO, editors. Unequal opportunity: Health disparities among gay and bisexual men in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 35–71.

40. Collins FH, Sutherland MA, Kelly-Weeder S. Gender differences in risky sexual behavior among urban adolescents exposed to violence. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2012;24:436–442. [PubMed]

41. Stephenson R, Rentsch C, Salazar LF. et al. Dyadic characteristics and intimate partner violence among men who have sex with men. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:324–332. [PMC free article][PubMed]

42. Kaschak E. Intimate betrayal: domestic violence in lesbian relationship. Women Therapy.2001;23:1–5.