| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Abdullah Bakhsh, MD | Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia |

| Bryan Morse, MD | Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Surgery, Atlanta, Georgia |

| Christopher Funderburk, MD | Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Surgery, Atlanta, Georgia |

| Patrick Meloy, MD | Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia |

| Katie Dean, MD | Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia |

| Jeffrey Siegelman, MD | Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia |

| Todd Taylor, MD | Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia |

Diagnosis: traumatic ventricular septal defect

Diagnosis: Traumatic Ventricular Septal Defect

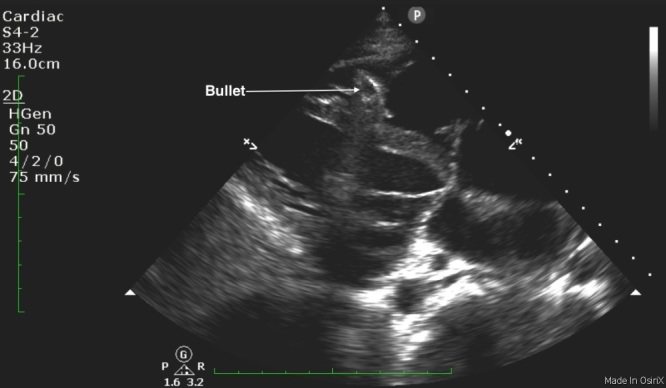

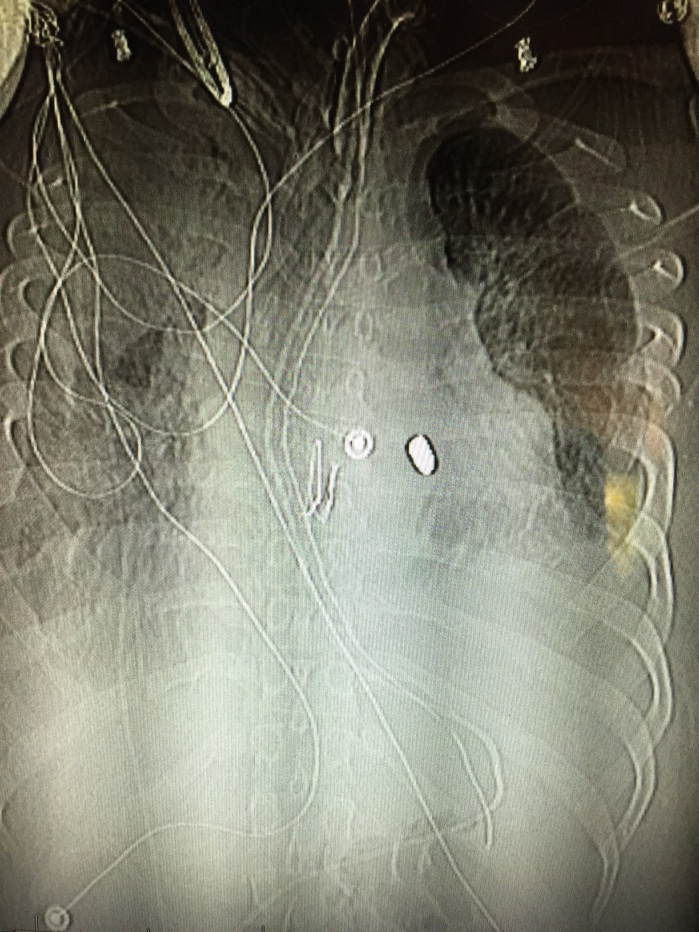

He was taken emergently to the operating room (OR) for exploration where he was found to have a ventricular septal defect (VSD), which was repaired. After a prolonged hospital stay, he was discharged to a long-term acute care facility for ventilator weaning. This patient is no longer dependent on the ventilator and is neurologically intact with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 15 and a Modified Rankin Scale of zero. He currently lives with a retained bullet fragment in his right ventricle. Traumatic VSD is a rare occurrence in cases of penetrating cardiac injury, with an incidence of only 1% to 5%.1 In patients who respond to resuscitation, as evidenced by systolic blood pressure >60mmHg to <100mmHg, there is evidence that they would benefit from emergency thoracotomy (ET [immediate thoracotomy performed in the OR]), as opposed to ED thoracotomy (EDT [immediate thoracotomy performed in the ED]). In these patients, survival can reach 75% to hospital discharge. Those patients who do not respond to the initial resuscitative effort have only a 25% survival rate after an EDT.2 Ultrasonography, performed during the initial survey of a trauma patient, has promise as a diagnostic modality for a variety of foreign bodies with a sensitivity and specificity of 96.7% and 70%, respectively.3 The chest film in the trauma bay showed a bullet fragment overlaying the cardiac shadow; however, given that only a single anteroposterior view was obtained it was difficult to ascertain the exact location of the bullet fragment. The use of ultrasound has the ability to detect intracardiac foreign bodies.

Footnotes

Section Editor: Sean O. Henderson, MD

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Abdullah Bakhsh, MD, Emory University School of Medicine, 68 Armstrong St. SE, Atlanta, GA 30303. Email: abdullahbakhsh@hotmail.com. 1 / 2016; 17:84 – 85

Submission history: Revision received August 17, 2015; Submitted October 4, 2015; Accepted November 1, 2015

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Sugiyama G, Lau C, Tak V, et al. Traumatic ventricular septal defect. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91(3):908-10.

2. Van Waes OJ, Van Riet PA, Van Lieshout EM, et al. Immediate thoracotomy for penetrating injuries: ten years’ experience at a Dutch level I trauma center. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2012;32(5):543-51.

3. Nienaber A, Harvey M, Cave G. Accuracy of bedside ultrasound for the detection of soft tissue foreign bodies by emergency doctors. Emerg Med Australas. 2010;22:30-4.

Parasternal long axis clip demonstrating a bullet fragment within the right ventricle.