| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Kristie A Robson, MD, LCDR, MC, USN | Naval Medical Center Portsmouth, Department of Emergency Medicine, Portsmouth, Virginia |

ABSTRACT

We report the case of a 22-year-old Marine who presented to the emergency department, after a martial arts exercise, with transient weakness and numbness in all extremities. Computed tomography cervical spine radiographs revealed os odontoideum. Lateral flexion–extension radiographs identified atlanto-axillary instability. This abnormality is rare and can be career ending for military members who do not undergo surgical fusion.

INTRODUCTION

Os odontoideum is a congenital or posttraumatic abnormality of the second cervical vertebrae in which the odontoid process is separated from the body of the axis by a transverse gap.1 This lesion can look like a fracture at the base of the odontoid. The lesion is frequently asymptomatic. Discovery of this cervical abnormality in an active-duty Marine Corps Private First Class occurred after trauma from martial arts training. This case report will review clinical presentations, diagnostic studies, and treatment options for os odontoideum.

CASE REPORT

A 22-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of diffuse numbness and weakness in all extremities after head trauma during a martial arts exercise. He was thrown by his right arm and landed on the top of his head. The patient stated that he was unable to move for approximately 8 minutes secondary to the “wind being knocked out of him.” He regained all sensation and strength by the time he reached the ED 20 minutes later by ambulance. His only complaint on arrival was pain in the midline, occipito-cervical region of his posterior neck. The patient was an active duty Marine Corps Private First Class with no significant medical history or history of head or neck trauma.

Physical examination revealed a fit young man on a backboard with a rigid cervical spinal collar in place. Vital signs were all within normal limits. His head was atraumatic. Patient had palpable midline posterior cervical spinal tenderness along C1 to C2 with no step-offs noted. Cranial nerves were intact, and he had no sensory or motor deficits on his neurologic examination. The remainder of his examination was without abnormalities.

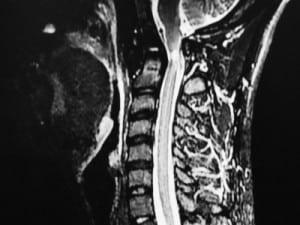

A noncontrast cervical spine computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained for further evaluation of his midline spinal tenderness and transient neurologic complaints. The CT revealed os odontoideum, which is demonstrated on the existing Figure 1. The radiologist could not exclude an acute subluxation and associated cord injury on CT alone and recommended a magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the cervical spine. MRI obtained in the ED showed a focal 7-mm craniocaudal axis region of myelomalacia at the C1 to C2 level (Figure 2). Findings were not thought to represent acute cord edema, but rather a chronic condition associated with the os odontoideum.

After neurosurgery was consulted, the patient was discharged home in a rigid cervical spinal collar and evaluated by neurosurgery the next day. Flexion/extension radiographs performed the next day showed instability, exacerbated on flexion, between the articulation of C1 and the C2 os odontoideum (Figure 3). The remainder of his cervical vertebral bodies had normal alignment with no additional abnormal translation. The patient was offered surgical fixation for his atlantoaxial instability.

DISCUSSION

Os odontoideum is an independent ossicle of variable size with smooth circumferential margins separated from a foreshortened odontoid peg.1 The ossicle stands apart from the hypoplastic dens and can adopt 2 anatomic types: orthotopic and dystopic.1 An ossicle located in the position of the normal odontoid is referred to as orthotopic. The ossicle is considered dystopic if it appears near the occiput in the area of the foramen magnum.2 The incidence of os odontoideum is unknown because the lesion is usually asymptomatic.2

The presentation of os odontoideum can vary from an incidental radiographic finding to severe findings of myelopathy, vertebral artery compression, and intracranial manifestations.1 Neurologic symptoms can vary from transient episodes of paresis after trauma to complete myelopathy from cord compression.2 Neck pain, torticollis, or headache can be caused from local irritation of the atlantoaxial joint.2 Compression of the vertebral artery can cause cervical and brainstem ischemia presenting as seizure, syncope, visual disturbances, and vertigo. Our patient experienced a transient episode of paresis associated with mild trauma.

Radiographic findings for os odontoideum consist of a free ossicle with smooth, sclerotic borders, usually half the size of a normal dens. An acute fracture would have a thinner and irregular space instead of the wide and smooth space of os odontoideum. CT scans with reconstruction views and MRIs are helpful in making the diagnosis. But initial routine cervical spine radiographs with an open-mouth odontoid view will also make the diagnosis. Lateral flexion and extension radiographs can detect instability. Instability in an adult is defined as greater than 3 mm of anterior and posterior displacement of the atlas on the axis.2 This number increases to greater than 4 to 5 mm in children. Our young Marine had 5.1 mm of anterior translation of the articulation between C1 and the os odontoideum on flexion imaging. The remainder of his cervical vertebral bodies had normal alignment with no additional abnormal translation.

Indications for operative stabilization of the os odontoideum are symptomatic neurologic involvement, including transient symptoms; instability of >5 mm posteriorly or anteriorly; progressive instability, and persistent neck complaints.2 The primary concern in this odontoid abnormality is the ability of the abnormal atlantoaxial joint to sublux or even dislocate with minor trauma, resulting in death or permanent neurologic damage.2 Service members who undergo surgical fixation will be able to continue on active duty on a case-by-case basis. Aviators or service members who require full atlantoaxial range of motion will undergo a military medical board review to determine fitness for duty. This Marine will be able to continue on service after surgical fixation. If he had, however, decided not to undergo surgery, he would not be recommended for continued military service by neurosurgery.

In summary, os odontoideum is an uncommon, but important cervical spine abnormality that can be associated with significant spinal cord and vertebral artery injuries and should be considered when a young person has symptoms consistent with upper cervical spine compression. Surgical fixation for patients with instability can save a military career and prevent catastrophic neurologic insult after minor trauma in the future.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Sean Henderson, MD

Submission history: Submitted July 7, 2010; Revision received January 5, 2011; Accepted April 4, 2011

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

DOI: 10.5811/westjem.2011.4.2029

Address for Correspondence: Kristie A. Robson, MD, LCDR, MC

USN, Naval Medical Center Portsmouth, Department of Emergency Medicine, 620 John Paul Jones Cir, Portsmouth, VA 23708-2197

E-mail: Kristie.robson@med.navy.mil

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the US Government.

REFERENCES

1. Arvin B, Fournier-Gosselin MP, Fehlings M. Os odontoideum: etiology and surgical management.Neurosurgery. 2010;;66:A22–A31.

2. Warner W. Pediatric cervical spine. In: Canale ST, Beaty JH, editors. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2007. pp. 1879–1898.