| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Brita Zaia | Stanford University Medical Center, Palo Alto, CA |

| Laleh Gharahbaghian, MD | Stanford University Medical Center, Palo Alto, CA |

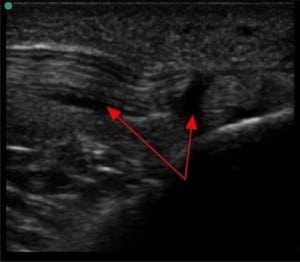

A 51-year-old female with a history of gout, hypertension and diabetes presented to the emergency department with one week of increasing pain and swelling of her left knee, just below the patella. She denied trauma, fever and calf pain. She took Ciprofloxacin for 14 days for a urinary tract infection. She was afebrile with stable vital signs, and the exam revealed mild swelling, increased warmth, and tenderness overlying the left tibial tuberosity. There was full range of motion at the knee. A bedside ultrasound (US) confirmed the diagnosis (Figure 1 and and 2).

Patellar tendonitis (PT) is characterized by well-localized anterior knee pain, along the patellar tendon distribution. The pain is often exacerbated by moving from sitting to standing or walking uphill.3 Causes of PT include repetitive use, jumping sports, trauma and fluoroquinolone use.3Fluoroquinolone-associated tendinopathy and tendon rupture occurs days to weeks after starting the medication.4 The risk increases in the following patients: older than 60 years, taking steroids, renal disease and recipients of kidney, heart, or lung transplants.4

Bedside US can be used to evaluate musculoskeletal injuries, including fracture, dislocation, joint effusion and tendon tears.5 A high frequency linear transducer was used first in longitudinal plane, placed over the tibial tuberosity evaluating the patellar tendon and then laterally in transverse plane evaluating for joint effusion. It illustrated absence of knee joint effusion and presence of inflamed patellar tendon. This patient was instructed to stop taking Ciprofloxacin, and was treated with anti-inflammatory pain medications and rest.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Rick A. McPheeters, DO

Submission history: Submitted August 4, 2010; Accepted October 11, 2010

Reprints available through open access at http://scholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Laleh Gharahbaghian MD FAAEM, Director, Emergency Ultrasound Fellowship, Clinical Instructor,

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Bianchi S, Martinoli C, Abdelwahab IF. Ultrasound of tendon tears. Part I: general considerations and upper extremity. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34:500–12. [PubMed]

2. Sisson C, Nagdev A, Tirado A, et al. Ultrasound diagnosis of traumatic partial triceps tendon tear in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Med. 2009 Feb 5; Epub ahead of print.

3. Schmidt MJ, Adams SL. Tendonopathy and Bursitis. In: Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R, editors.Rosen’s Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2009. p. 1492.

4. Waknine Y. Fluoroquinolones Earn Black Box Warning for Tendon-Related Adverse Effects. Medscape Medical News website. Available at http://www.fda.gov/medwatch/safety/2008. Accessed May 9, 2010.

5. Rippey JC, Royse AG. Ultrasound in trauma. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2009;23(3):343–62.[PubMed]