| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Jessica Thomas, MD | Department of Emergency Medicine, Madigan Army Medical Center, Tacoma, Washington |

| Gregory Moore, MD, JD | Department of Emergency Medicine, Madigan Army Medical Center, Tacoma, Washington |

Introduction

Methods

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

INTRODUCTION

More than any other area of emergency medicine, legal issues are paramount when caring for an agitated patient. It is imperative to have a clear understanding of these issues to avoid exposure to liability. These medico-legal issues can arise at the onset, during, and at discharge of care and create several duties. At the initiation of care, the doctor has a duty to evaluate for competence and the patient’s ability to consent. Once care has begun, patients may require restraint if they become combative or violent. If restraints are placed, the physician has a duty to protect the patient and should fill out all appropriate paperwork as they have decided to take away the patient’s liberty. Use of restraints may precipitate issues of battery and false imprisonment. Finally, prior to discharge, the physician has a duty to determine if there have been any direct threats made regarding a third party and if there is a duty to warn. These medico-legal issues will be illustrated using actual court cases. The purpose of this paper is to educate practicing emergency physicians (EP) on high-risk legal issues concerning the agitated patient, so that liability can be avoided.

METHODS

The authors with a combined 15 years of medico-legal experience developed a focused list of topics and concerns with regards to liability concerning the agitated patient. For the purposes of this paper, an agitated patient was one considered to be violent, delirious, or presenting with a psychiatric emergency. Cases that applied to these topics were then individually and randomly selected. For each topic, an attempt was made to identify both a classic/defining legal case followed by a more current example.

Consent/Competence/Restraint

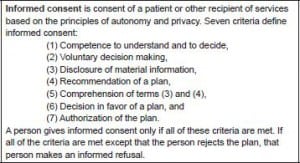

Before undesired medical care can be undertaken, the EP must first understand the components and requirements of informed consent. Traditionally, patients have the right to determine if and when they want medical care and what care they desire.1,2 Patients enter into contractual obligations with physicians by granting permission for medical care and treatment. This is referred to as consent for treatment. An analysis of what constitutes consent and the related topic of competence is helpful in determining what care should be provided to the agitated patient in the emergency department (ED) (Figure 1).3

Definition of informed consent.6

Consent is defined as a voluntary agreement by a person in the possession and exercise of sufficient mental capacity to make an intelligent choice to do something proposed by another.4 Consent is generally considered as either implied or expressed. Implied consent is defined as the signs, actions, facts, or inaction that raises the presumption of voluntary agreement. Thus, a patient presenting to an ED for assistance by himself or via another concerned person or agency, would generally be considered as providing implied consent. 4 The exception would be if the patient is competent and refusing. Another specific example would be when a patient holds his arm out for a blood sample draw. The action, without words, implies consent. Expressed consent is when the patient, in verbal or written form, gives consent for a procedure. If consent is given verbally, it is optimal for the provider to document this on the chart. As the severity and importance of the decision increases, the provider should consider written rather than verbal consent. Usually, whether to use verbal versus written consent is a personal practice decision of the provider.

Individuals are entitled to make decisions about their healthcare if they are deemed competent. Competency is defined as the capacity of a person to act on his/her own behalf; the ability to understand information presented, to appreciate the consequences of acting–or not acting–on that information, and to make a choice.4 Seven criteria must be met in order to obtain informed consent (Figure 1). Adults are presumed competent to grant consent for proposed medical treatment. An incompetent adult patient who is incapacitated by physical or mental illness and is unable to understand the nature and consequences of his or her actions cannot give valid consent to proposed treatment. In the case of an incapacitated adult, consent must be obtained from someone who is authorized to consent. This may be someone that the patient requested when competent through a “durable power of attorney,” or if a court has decided the patient is incompetent, the patient’s court-appointed guardian must authorize treatment. If a physician has determined that a patient is incapable of comprehending the nature and consequences of his or her conduct but the patient has not been judged incompetent, most courts will accept the consent of the patient’s next of kin. It is wise to document that the family desired and approved the proposed treatment. This “substituted consent” is not ideal because each individual is considered the true authority on deciding his or her care.1,2,4

The law usually presumes patient consent in an emergency. Courts have supported EP actions, without consent, when the purpose was to preserve the patient’s life or health.2,5 Courts assume that a reasonable, competent adult would want to be healthy. Specifically in the case of an agitated patient, the EP can safely assume that the act of presenting to the ED is at least an implied consent for evaluation and treatment. The EP should quickly decide if the patient is competent. If competent, the patient must give express consent before proceeding, but otherwise the physician is at liberty to provide care. Documentation of factors that led to the decision on competence is imperative, and supportive documentation of coworkers present is optimal. For example, having another present physician state on the chart “I agree,” will be extremely supportive if legal action is taken later by the patient. If time permits, an actual court order is ideal. If the family is present, explaining the need for action, and documenting their support is essential. The more life-threatening the emergency, the more the physician should be willing to proceed with the plan of care. If competency is not able to be determined, it is best to err on the side of treatment and safety. Battery and false imprisonment are much easier to defend than passive negligence. In these situations, it is imperative to document that (1) an emergency existed, (2) there was an inability to get consent, and (3) the treatment was for the patient’s benefit.1

A classic case that illustrates the court’s analysis of consent and capacity is Craig L. Miller v. Rhode Island Hospital et al. 7 The patient, Miller, drank several alcoholic beverages and then was involved in a serious motor vehicle accident. Miller was transported to Rhode Island Hospital where his blood alcohol level was found to be 0.233. He complained of pain in his head, eyes, back, and ribs, as well as blurry vision because of the blood in his eyes. Because of his level of intoxication and the nature of Miller’s accident, “physicians decided to perform a diagnostic peritoneal lavage. (At that time, a standard procedure under conditions concerning for internal bleeding.)”8 After discussion of the procedure with the patient, Miller refused. However, it was determined that he was not competent to make this decision based on his level of intoxication. He was physically restrained and the procedure was performed anyway. The patient later brought suit for battery.7

The Supreme Court of Rhode Island held that medical competency was the relevant standard for physicians to judge conscious patients in these circumstances (ie, whether the patient is able to reasonably understand the medical condition and the nature of any proposed medical procedure, including the risks, benefits, and available alternatives). In this case, the court decided in favor of the defendant hospital. The court concluded, “A patient’s intoxication may have the propensity to impair the patient’s ability to give informed consent.” 7

Another landmark case that further illustrates this issue was Youngberg v. Romeo.9 Romeo was a mentally retarded patient. Until the age of 26, he lived with his parents, but after his father died his mother was not able to care for him or control his violent behavior. She requested that he be permanently admitted to a Pennsylvania institution. While committed, he suffered several injuries, both from his own violence and the reactions of other residents. On multiple occasions he was physically restrained against his wishes. His mother became concerned with these injuries and objected to his treatment on several occasions before filing suit against the institution, claiming that the patient had constitutional rights to safe conditions of confinement, freedom from bodily restraint, and training and development of needed skills. She felt the institution knew, or should have known, about his injuries, but failed to take appropriate preventive procedures.9

In Romeo, the Supreme Court of the United States supported involuntarily restraining a patient for safety reasons. The court has given great respect and latitude to physicians regarding violent patients, stating, “We have established that the patient retains liberty interests in safety and freedom from bodily restraint. Yet these interests are not absolute, there are occasions in which it is necessary for the state to restrain the movement of residents – for example, to protect them as well as others from violence.”9 The Model Penal Code allows “an exception from the assault statute for physicians… who act in good faith in accordance with the accepted medical therapy.”10

Duty to Protect

Realize, when you deprive someone of his/her freedom, you assume a “fiduciary responsibility.” A fiduciary is similar to a parent, guardian, or prison. It is a relationship of responsibility for the health and welfare of someone else. The importance of liability and responsibility for monitoring a patient after he has been restrained was illustrated in the case Estate of Doe v. ABC Ambulance.11 A 32-year-old schizophrenic threatened to kill his psychologist and was taken to the ED. When informed that he was going to be involuntarily admitted, he became violent. The patient was physically restrained in 4-point restraints, chemically sedated, attached to a gurney on a backboard, and turned upside down. A towel was then placed over his mouth to prevent spitting and a sheet was laid over him to decrease outside stimulus. His complaints of inability to breathe were ignored. When being transferred later to the psychiatric ward, it was noticed that one of his protruding hands was blue. The patient was uncovered and found to be in cardiopulmonary arrest from which he did not recover. His estate was awarded $2 million.

A similar event occurred in Larry Gazda v. Pima County.12 Wendy Gazda was a 32-year-old patient who died of restraint asphyxia while being held facedown by up to 5 mental-health technicians and security guards in a struggle that lasted 15 to 30 minutes. She ended up with her face in a pillow that had been placed on the floor to protect her head. She was turned over after she became still and somebody noticed her hand had turned blue. Her father argued that his daughter was “negligently, unreasonably and violently restrained” by untrained and poorly supervised staff. After the death, state and federal investigations uncovered numerous deficiencies in the hospital’s training and staffing, as well as in its policies and procedures. The hospital settled for $105,000.12 These cases illustrate the lethal risks when restraints are used and the importance of ensuring safe administration.

Every provider or hospital should have a systematic approach to the safe restraint of patients. The American College of Emergency Physicians has proposed a model policy on the use of patient restraints (Figure 2). The Joint Commission has published an extensive guideline on requirements for the use of restraints. It can be seen at crisis prevention website.29 It would be optimal for all ED providers to be familiar and comply with this document.

American College of Emergency Physicians policy statement: use of patient restraints.27

Battery

Battery is the intentional infliction of a harmful or offensive bodily contact. (See Figure 3 for complete definition.) One does not have to be hurt but merely suffer damage to one’s dignity.13 Courts are very protective of the “sanctity of person,” “bodily integrity,” and “personal autonomy” as a fundamental personal right.14 To be “intentional” simply implies that the actor wanted to do the action, regardless of whether the intent was to help the patient. A physician must never physically invade or touch a competent patient without his/her consent, or the physician may be liable for battery. Recoverable damages can be “general,” such as compensation for the harm done, and “special,” such as compensation for medical charges, lost wages, and other expenses. These may not be covered by standard medical malpractice insurance.

Definition of battery.

A defining case of battery was Pugsley v. Privette in which a 44-year-old woman agreed to undergo an elective exploratory laparotomy to identify the etiology of vaginal bleeding.15 As this was not an emergent case, the patient signed a standard consent form prior to the surgery. However, the patient repeatedly requested to have her general surgeon present alongside the gynecologist. Although the chief of surgery initially agreed to be present, at the start of the patient’s surgery he was unable to be found and the patient reiterated that she did not want to continue with the operation under those circumstances. Despite her requests, the patient was anesthetized and a bilateral oophorectomy was performed. During the procedure, her ureter was damaged and the patient underwent a protracted postoperative course. The patient sued for medical malpractice and battery. The physicians were not found liable for malpractice as ureteral injury is a known and recognized complication, but the patient was awarded $75,000 in damages for battery.15

This relates to an agitated patient as well. If a physician restrains a competent patient for convenience without clear indication for physical contact, they can still be liable for battery.

False Imprisonment

False imprisonment is the intentional infliction of a confinement. It represents confinement and deprivation of personal liberty, for any length of time, without consent.16 (See Figure 4 for complete definition.) Physical restraints do not need to be placed on a patient to be considered false imprisonment. Just the threat of physical harm, such as a large security guard posted at the patient’s doorway, is still considered withholding the patient’s right to leave. Damages may be awarded, even in the absence of physical harm, for inconvenience, mental suffering, and humiliation. These may not be covered by standard malpractice insurance policies.

A patient must be deemed incompetent and a danger to himself or someone else before his rights may be taken away and the patient placed in restraints and kept in the hospital against his wishes. If a patient does not wish to stay but has not been deemed incapable of making this decision, the hospital and its staff can be held accountable for false imprisonment. A classic case is Barker v. Netcare Corp.17 Janice Barker presented to Netcare for mental evaluation after reportedly being raped the week before. On arrival the patient was distraught and agitated. The psychiatrist on call was contacted and ordered Lithium and Lorazepam to calm the patient. These did not seem to affect the patient and she was overheard making vague statements about being “put out of her misery.” The social worker interviewed the patient and felt she should be a voluntary holdover to stay until a psychiatrist could formally evaluate her in the morning. Barker initially agreed but later left the hospital for a short amount of time. On her return, the patient was offered a shower and was heard banging her head against the wall while in the bathroom. Barker was offered the choice to stay in the hospital or be discharged home with her husband. However, Barker was unable to reach him and became more agitated. The patient again left the hospital, but this time was brought back by campus police as hospital employees were concerned about her mental state due to banging her head against the wall, inability to reach her husband, and the patient only wearing a hospital gown while outside. On return, Barker was placed in physical restraints, as she was now significantly more argumentative, although by nursing report, not combative. Barker was also restrained chemically with Benztropine and Haloperidol. Despite restraints being placed, the hospital failed to commence emergency involuntary commitment proceedings in accordance with Ohio law. Later, Barker brought suit for false imprisonment. The jury found that staff had intentionally restrained or confined Barker without lawful privilege and without consent. The jury found that medical staff acted with insult and actual malice and awarded Barker $150,000 in damages.17 This case demonstrates that even if the staff feels they are doing what is best for the patient, if the proper protocols are not followed, it is still considered false imprisonment.

Definition of false imprisonment.16

Another case where the hospital had good intentions but did not follow proper protocol is Heath v. Peachtree Parkwood Hospital, Inc.18 A woman was held in a psychiatric facility for 3 days without her consent. As in the previous case, no papers for involuntary commitment were completed. After this period, an evaluation determined her to be a danger, and involuntary commitment papers were completed. She successfully sued the physicians and hospital that cared for her during the initial 3 days but absolved the later treating physicians.18 Both cases emphasize the importance of proper statutory documentation.

Every state has a law defining the procedure for holding patients against their will, and the EP should become familiar with the state’s statutes in which he or she practices. In the preceding cases, it is clear that if physicians comply with the state law and procedural paperwork they will be given great latitude in holding someone for a period of time to further evaluate and assess the danger. The EP must immediately document and fill out appropriate forms when restraining or involuntarily committing a violent patient.

Duty to Warn

An expectation of confidentiality between physician and patient is an essential component of the therapeutic relationship. This duty to maintain confidentiality enables the sharing of personal and sensitive patient information in order to best serve the patient. The landmark case of Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California established a new duty for a physician to warn a third party regardless of this duty to confidentiality by concluding that the “protective privilege ends where the public peril begins.” 19

In Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California, the parents of Tatiana Tarasoff argued to the California Supreme Court that their daughter’s death occurred after the defendants negligently failed to warn them that the killer had confided his intention to kill Tatiana to his treating psychologist, Dr. Lawrence Moore. Campus police, on the request of Dr. Moore, had briefly detained Prosenjit Poddar, after Poddar confided his intention to kill Tatiana Tarasoff. Neither the victim nor her parents were made aware of Poddar’s intention before he subsequently killed her. The plaintiffs alleged that the defendant therapist did in fact predict that Poddar would kill and that harm to a third party was foreseeable. The court found that therapists not only had a duty to their patients, but also a duty to warn a third party of foreseeable violence.19 This was the first case where the courts deemed third-party safety superseded patient confidentiality. As can be seen from this case, the physician cannot just inform security forces or the police; the intended third party must be warned to the best effort of the physician for the physician to have met this duty.

Actions are considered foreseeable when a specific person(s) is named as the target. When the patient states a wish to “blow up the postal service,” there is no specific target, therefore, no duty to warn. The California Supreme Court upheld that “in the absence of a readily identifiable foreseeable victim, there is no duty to warn.” The existence of an identifiable group of potential victims is insufficient to create a duty to warn.20

The physician’s duty to warn has been supported in other states since the Tarasoff case, as in Dorothy McGrath et al v. Barnes Hospital et al.21 In this Missouri court case, a paranoid schizophrenic being treated in an inpatient setting admitted several times to having thoughts of stabbing his mother with a kitchen knife. Reportedly, he had made this statement many times in the past and so no attempt was made to warn his parents prior to release from the inpatient care setting. The night that he was released to the care of his parents he stabbed both of them, killing his father and severely injuring his mother. The hospital was sued successfully by the patient’s surviving mother for failure to warn, despite a defense that the family was already aware of this risk of violence given his long history of mental illness. The court awarded $2 million.

In general, clinicians should exercise their duty to warn and protect when 3 elements are met. First, a clearly identifiable person or group is at risk. Second, risk of harm includes severe bodily injury, death, or psychological harm. Third, the danger is imminent and creates a sense of urgency.22

Later in California, the court further developed the Tarasoff ruling in Ewing v. Goldstein to include acting on third-party information that indicates a possible threat. The parents of a patient informed his psychiatrist that their son planned on killing his ex-girlfriend’s new boyfriend. The psychiatrist did have the patient admitted to a psychiatric hospital but did not warn the intended victim. On the patient’s release, he killed the new boyfriend and then committed suicide. The court ruled that the psychiatrist had a duty to warn because he had information about a foreseeable event.23,24

The Duty to Warn mandate is determined on a state-by-state basis; it is not a national or federal law. While many states have ruled similarly to California it is not universal, and clinicians should be familiar with the law in their jurisdictions. However, it is very easy, no matter which state you live in, to notify all parties involved and not worry about your state’s law. It is very unlikely that a court would rule against a physician who intentionally violates HIPAA in order to protect another person. The table demonstrates the various Duty to Warn state policies as of early 2011.

DISCUSSION

It is clear that inattention to key legal concepts when caring for an agitated patient may lead to significant liability and personal financial risk. First, a physician must determine a patient’s ability to give (or refuse) consent for treatment [competence/consent]. Second, if a patient’s liberty has been taken away, it is the physician’s responsibility to ensure the patient’s health and safety [duty to protect]. Third, no one should touch or hold a patient against his will except in the case of an emergency and the proper paperwork has been filled out [battery/false imprisonment]. Last, if direct threats have been made during the patient’s encounter the physician has a responsibility to inform the third party of possible danger [duty to warn].

LIMITATIONS

Cases were individually selected at random by the authors if they directly applied to this focused topic. An extensive search using a legal engine was not done, and there may be other relevant cases. The goal of our study was to briefly educate and illustrate a selected medical legal issue in emergency medicine using a limited number of classic and current cases.

CONCLUSION

In caring for an agitated patient in emergency medicine, multiple areas of medico-legal risk arise, including competence/consent, duty to protect, battery/false imprisonment, and duty to warn. As compared to the standard practice of the specialty, these topics, intuitively, occur more frequently. This paper has demonstrated that multiple court cases support the conclusion that it behooves the practicing emergency physician to be familiar with these concepts in order to avoid liability.

Footnotes

Address for Correspondence: Jessica Thomas, MD. Madigan Army Center, 2270 Simmons St., United A DuPont, WA 98327. Email: jsthomas156@gmail.com.

Submission history: Revision received October 30, 2012; Submitted February 8, 2013; Accepted April 2, 2013

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.