| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Sarah Lopez, MD, MBA | Los Angeles County USC Medical Center, USC Keck School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Angeles, California |

| Sean O. Henderson, MD | Los Angeles County USC Medical Center, USC Keck School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Angeles, California |

ABSTRACT

Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis (TPP) attacks are characterized as recurrent, transient episodes of muscle weakness that range from mild weakness to complete flaccid paralysis. Episodes of weakness are accompanied by hypokalemia, which left untreated can lead to life-threatening arrhythmias (6). In this case study, we followed a patient’s potassium levels analyzing how they correlate with electrocardiogram changes seen while treating his hypokalemia and ultimately his paralysis.

INTRODUCTION

The overall incidence of thyrotoxic periodic paralysis (TPP) is 0.1–0.2% in North America, but varies dramatically among certain populations.1 In Chinese and Japanese patients, the incidence is 1.8–1.9%, the highest among any one population.2 Attacks are characterized as recurrent, transient episodes of muscle weakness that range from mild weakness to complete flaccid paralysis. Episodes of weakness are often accompanied by hypokalemia, and treatment of the underlying thyrotoxicosis will resolve symptoms of muscle weakness.3 Aggressive replacement of potassium can cause a drastic rebound hyperkalemia, but left untreated, severe hypokalemia can also cause life-threatening arrhythmias.4–6

In this case, we report the presence of 3 distinct arrhythmias in a single patient as his potassium levelchanged during an episode of acute TPP.

CASE

A 29-year-old Asian male presented to the emergency department (ED) with symmetric paralysis of his lower extremities and weakness of his upper extremities that developed overnight. He had been recently diagnosed with hyperthyroidism 10 days prior, after presenting with 4 months of palpitations, muscle pain, cramping, and stiffness. He was started on propranolol and methimazole at that time. After resolution of his original symptoms, he stopped taking the medications and presented to the ED with complete paralysis of his lower extremities.

On further history, it was discovered that over the preceding 4 months the patient had clinical features of TPP that had been subtle, with reports of transient lower extremity weakness occurring that resolved without medical intervention.

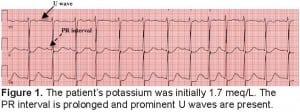

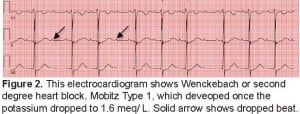

On physical exam, the patient had symmetrical weakness and was unable to move his legs, but able to move his upper body, with sensation still intact. Upon initial laboratory evaluation, the basic metabolic panel (BMP) demonstrated a potassium level of 1.7 milliequivalent (mEq/L). The free thyroxine (T3) level was elevated at greater than 8.8 ng/dL, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) was decreased at 0.010 μlU/mL. The initial electrocardiogram (ECG) showed 1st degree heart block with prominent U waves (Figure 1). The PR interval was prolonged to greater than 0.2 sec as seen in leads V1 & V5, and U waves were present in all leads. There were no prior ECGs to compare these findings. Treatment was initiated with slow potassium repletion, but the potassium continued to drop to 1.6 mEq/L and the ECG showed 2nd degree heart block, Mobitz Type I, best seen in Lead II and V1 (Figure 2).

The patient’s potassium was initially 1.7 meq/L. The PR interval is prolonged and prominent U waves are present.

This electrocardiogram shows Wenckebach or second degree heart block, Mobitz Type 1, which deveoped once the potassium dropped to 1.6 meq/ L. Solid arrow shows dropped beat.

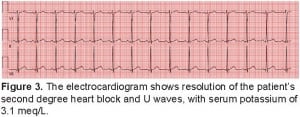

The development of this 2:1 AV block coincided with increased weakness of more proximal muscles and decrease in reflexes. However, the patient’s airway was never compromised because his respiratory muscles were always intact. The paralytic attack was aborted with a combination of cautious potassium replacement, methimazole and parenteral propranolol. The patient received initial doses of potassium chloride 10 mEq intravenously and 40 mEq orally. A repeat BMP 3 hours later revealed a potassium level of 3.10 mEq/L and magnesium level of 1.8 mmol/L. Subsequently, the PR interval was noted to shorten and the rhythm returned to normal sinus (Figure 3).

The electrocardiogram shows resolution of the patient’s second degree heart block and U waves, with serum potassium of 3.1 meq/L.

Our patient exhibited numerous ECG changes due to hypokalemia secondary to thyrotoxicosis, with associated thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. Symptoms resolved, along with the seen ECG changes, with cautious potassium repletion and control of the underlying thyrotoxicosis.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Rick A. McPheeters, DO

Submission history: Submitted May 31, 2011; Revision received October 10, 2011; Accepted November 11, 2011

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

DOI: 10.5811/westjem.2011.11.12127

Address for Correspondence: Sarah Lopez, MD, MBA, LAC+USC Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, 1200 N. State Street, Los Angeles, CA 90033

Email: sarita1819@gmail.com

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Kung AW. Clinical review: Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis; a diagnostic challenge. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(7):2490–5. EPub; [PubMed]

2. McFadzean AJS, Yeung R. Periodic paralysis complicating thyrotoxicosis in Chinese. Br Med. 1967;1:451–455.

3. Birkhahn RH, Gaeta TJ, Melniker L. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis and intravenous propranolol in the emergency setting. J Emerg Med. 2000;18(2):199–202. [PubMed]

4. Tassone H, Moulin A, Henderson SO. The pitfalls of potassium replacement in thyrotoxic periodic paralysis: a care report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med.2004;26(2):157–161. [PubMed]

5. Kung AW. “Clinical review: Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis: a diagnostic challenge” J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;91(7):2490–5. [PubMed]

6. Osadchii OE. Mechanisms of hypokalemia-induced ventricular arrhythmogenicity.Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2010;24(5):547–59. [PubMed]