| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Robin R. Hemphill, MD, MPH | Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Nashville, TN |

| Sally A. Santen, MD | Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Nashville, TN |

| Benjamin S. Heavrin, MD, MBA | Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Nashville, TN |

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

The study objective was to determine whether surgeons and emergency medicine physicians (EMPs) have differing opinions on trauma residency training and trauma management in clinical practice.

Methods:

A survey was mailed to 250 EMPs and 250 surgeons randomly selected.

Results:

Fifty percent of surgeons perceived that surgery exclusively managed trauma compared to 27% of EMPs. Surgeons were more likely to feel that only surgeons should manage trauma on presentation to the ED. However, only 60% of surgeons currently felt comfortable with caring for the trauma patient, compared to 84% of EMPs. Compared to EMPs, surgeons are less likely to feel that EMPs can initially manage the trauma patient (71% of surgeons vs. 92% of EMPs).

Conclusion:

EMPs are comfortable managing trauma while many surgeons do not feel comfortable with the complex trauma patient although the majority of surgeons responded that surgeons should manage the trauma.

INTRODUCTION

Both emergency medicine (EM) and surgery residents require training in the care and management of acute trauma victims.1–4 At times this dual requirement can result in conflict between surgery residents and attendings who feel that only surgeons should run trauma resuscitations, and emergency medicine residents and attendings who feel that they are both capable and need to be able to care for trauma patients. However, as both groups struggle for control there is little published research as to the variability of who continues to take care of trauma victims once each group leaves their residency training and what their ongoing comfort level is with caring for the acutely injured trauma patient.

The purpose of this study was to survey practicing emergency physicians (EPs) and surgeons to determine who manages trauma patients in practice. We also sought opinions from each group as to who they felt was qualified to manage the initial resuscitation of the trauma victim, what their comfort level was in treating the trauma victim, and whether they felt that their trauma training during residency was adequate for their current practice.

METHODS

A survey was mailed to 250 board-certified EPs and 250 board-certified surgeons selected at random from the American College of Emergency Physicians and the American College of Surgeons membership directories, respectively. A follow-up mailing was sent to all non-respondents one month following the initial mailing. This survey was approved by the investigational review board.

The survey requested basic demographic data and information on the types of postgraduate and specialty training that each physician completed (Appendix). The survey then asked about who manages the trauma patient at the physician’s current hospital, and whether or not the physician is currently comfortable with handling the unstable trauma patient. The physicians were asked about their opinions of who should manage trauma. In the survey we did not attempt to define precisely what a “trauma patient” or a “trauma team” was. Instead, the cover letter asked respondents to consider who cared for “sick” trauma patients in their residency and who cared for these patients in their current practice (to include a multidisciplinary group of physicians on a trauma team). The initial responses were collapsed to “agree, neutral and disagree.” Data was analyzed using SPSS10-Mac. Chi-square, t-tests and odds ratios were calculated to compare responses between the two groups of physicians.

RESULTS

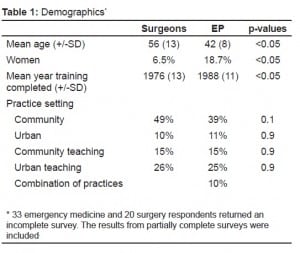

One hundred thirty-nine of 250 EPs (56%) and 126 of 250 (50%) surgeons responded. Demographic information is in Table 1. Residency training included defined months in trauma surgery for 52% of surgeons and 72% of EPs. During their residency, 72% of surgeons stated that surgery ran their traumas, and 19% stated that a trauma team ran their traumas. Only 7% of surgeons responded that during their residency the management of the trauma patient was shared with EPs. Fifty-six percent of EPs shared the care of the trauma patient with surgery when they were in training, while 23% stated that EPs were the primary trauma care providers, and 16% of traumas were managed by the surgery attending.

At their current hospital 38% of surgeons stated that trauma was managed by an EP, 50% by surgery (29% by a surgery team, and 21% by a surgery attending). Twelve percent of surgeons gave the answer of other, in which most commented that the trauma patient was cared for by both surgery and EPs. In their current practice, EPs stated that 60% of the initial management of the trauma patient is managed initially by the EP, while 24% is managed by a trauma team, and only 3% is managed by a surgery attending.

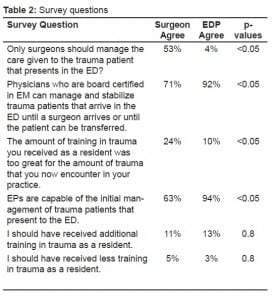

The opinions of the two groups on the management of trauma are in Table 2. Surgeons were more likely to believe that only surgeons should manage trauma upon presentation to the ED (53% vs. 4%, Odds ratio 26.4, 95% CI 10.8–64.2). This opinion was shared regardless of where the surgeons were practicing. However, only 60% of surgeons are comfortable with caring for the complex trauma patient, compared to 84% of EPs (Odds ratio 0.28, 95% CI 0.16–0.5). Fifty-six percent of surgeons who felt that only surgeons should take care of trauma did not, themselves, feel comfortable taking care of trauma patients.

While the majority of surgeons agreed that only surgeons should manage trauma, when given the opportunity to answer a question asking their opinion about whether EPs could manage the initial resuscitation of trauma patients the majority of surgeons (71%) seemed to agree that this was acceptable. The numbers were too small to comment on whether those who shared trauma training with EM residents had a more favorable view of the ability of EPs to care for the trauma patient.

The majority of surgeons and EPs did not feel that their trauma training should change. However, 24% of surgeons compared with 10% of EPs felt that they had received too much training in trauma for the amount of trauma that they now saw in their practice (Odds ratio 2.8, 95% CI 1.4–5.6).

DISCUSSION

Many medical centers that care for trauma patients have residency programs in both surgery and emergency medicine. In caring for the trauma patient, conflicts may arise as to who is the most appropriate physician to both run the trauma as well as perform procedures. Both specialties can claim that they need to learn how to care for the trauma victim.5 It is not uncommon for surgeons to claim that trauma is a surgical disease and, thus, only surgeons should be involved in the care of these patients.6 This may be particularly true at regional trauma centers where EM residents may be allowed only a marginal role in trauma resuscitation. EM residents can correctly claim that not all “Level I trauma patients” arrive at Level I centers. EPs must be competent in the management and resuscitation of the acute trauma patient when a surgeon is not immediately available. In many cases the EP is the only available physician with trauma experience at some facilities. If the patient is to survive until the surgeon arrives or until his transport to another facility, he must be managed by providers trained and skilled in the care of the trauma patients.

Moving beyond what individual practitioners may think about who should take care of the trauma patient, guidelines do exist, and in some cases may be at odds.7 The American College of Surgeons (ACS) Committee on Trauma publishes guidelines for trauma center designation, and a Level I designation requires trauma patients to be taken care of by surgeons. Since emergency medicine residency training requires that residents have opportunities to perform invasive procedures and direct major resuscitations (including trauma resuscitations), it is possible that the educational goals and guidelines for each specialty may conflict if surgeons feel that they are the only physicians capable of managing trauma patients.2,8

Many surgeons do not wish to incorporate trauma into their future clinical practice and most hospitals are not Level I trauma centers. Girotti et al.9 found that only 5% of surgeons wanted greater than 30% of their future practice to be trauma related. Richardson and Miller10 reported that less than 20% of surgery residents wanted to provide significant trauma care in their future practice. Given these findings it seems possible that many hospitals outside of the largest centers will have surgeons staffing them that neither want to take care of these patients, and in fact, may no longer feel comfortable taking care of trauma patients once they are a few years out of residency training. We were unable to find data indicating the long-term expectations of EPs as to how much trauma that they wanted to care for in their practice. However, given the realization of most EPs about the unexpected nature of many emergencies, it seems reasonable to assume that most EPs will have some expectation that they should and will care for trauma patients in the future.

In considering the response of EPs it is not surprising that they disagree with the statement that only surgeons should manage trauma patients. They also overwhelmingly agree that trained EPs can manage the initial resuscitation and management of the trauma patient until a surgeon arrives or until the patient is transferred. Eighty-four percent of EPs were comfortable managing the complex trauma patient compared with only 60% of surgeons. Given the numbers of practicing EPs currently caring for trauma at their hospital, their degree of comfort with the care of these patients, and the fact that they generally believe that they are capable of caring for these patients, it appears that EPs are active in trauma care once they graduate from residency.

The results of this survey indicate that once surgeons have graduated from residency many do not remain comfortable taking care of the complex trauma patient because they do not continue to care for trauma patients. This is in contrast to EPs, most of whom appear to remain comfortable with this type of patient.

This study has implications for facilitating a better understanding between surgeons and EPs in order to provide the highest quality of training in the care of the trauma patient. Understanding the role in trauma management that they are likely to play in their future practice may help each group understand the needs and goals of the other specialty while still in training. Further, given that some surgeons may not be comfortable providing routine trauma care once they move out of training, this study may help them understand that EM physicians both expect to manage and feel comfortable with providing care to trauma patients. Together these two groups may improve the care and outcomes of trauma patients, particularly those that present outside of the major trauma centers.

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations in this study. There was no way to confirm the perceptions of participants as to who is actually taking care of the trauma patient at their facility. Despite attempts to increase the number of returned surveys, the percentage of returned forms was below desired. Those who felt less opinionated may have been the ones who did not reply. These results may therefore reflect the response bias of those that feel most opinionate or passionate about this topic. It is possible that EM physicians that feel more comfortable taking care of trauma patients are over-represented by this survey and the same may be true for surgeons. Future survey research in this area may generate better response by using a combination of mailed surveys along with phone follow-up rather than a second mailing.

The difference in mean age between the two surveyed populations may suggest a bias in the responses between the surgeons and the EPs. New graduates of surgery programs who are more used to training alongside EPs may have different opinions about the ability of EPs to care for trauma patients. However, the age and sex differences between the groups reflect existing demographic status at our own institution and may be an accurate reflection of current demographic differences between these two specialties. The surgical specialty is currently older than emergency medicine and remains a male-dominated specialty.

Finally, while we were interested in the way surgeons and EM physicians are practicing compared to the way they were trained we did not explore the way in which the perceptions of these physicians may have changed over the interval between their training and their response to this survey. Future research could explore this area in greater detail.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, many surgeons do not feel comfortable managing the trauma patient, but they still appear to feel that the trauma patient is best managed by a surgeon. However, most recognize that the EP can adequately care for the initial trauma resuscitation. The majority of EPs feel both capable of managing the trauma patient and that the trauma patient can be managed by EPs.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Sean O. Henderson, MD

Submission history: Submitted September 17, 2008; Revision Received November 17, 2008; Accepted December 01, 2008

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Robin R. Hemphill, MD, MPH. Dept of Emergency Medicine, VUMC, 3401 West End Ave., Suite 100, Nashville, TN. 37203

Email: robin.hemphill@vanderbilt.edu

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Hockberger RS, Binder LS, Graber MA, et al. The model of the clinical practice of emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:745–770. [PubMed]

2. Program Requirements for Residency Education in Emergency Medicine [Internet]Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2001. Available at:http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/downloads/RRC_progReq/110emergencymed07012007.pdf Accessed November 2008.

3. Program Requirements for Residency Education in General Surgery [Internet] Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2001. Available at:http://www.ACGME.org Accessed November 05, 2008.

4. Wightman JM, Manuel TS, Hamilton GC. Objectives to direct the training of emergency medicine residents on off-service rotation: Traumatology, part 1. J Emerg Med. 1995;13:99–104. [PubMed]

5. Grasberger RC, McMillian TN, Yeston NS, et al. Residents; experience in the surgery of trauma. J Trauma. 1986;26:848–850. [PubMed]

6. Rotondo MF, McGonigal MD, Schwab W, et al. On the nature of things still going bang in the night: An analysis of residency training in trauma. J Trauma. 1993;35:550–555.[PubMed]

7. Howell JM, Savitt D, Cline D, et al. Level I trauma certification and emergency medicine resident major trauma experience. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3:366–370.[PubMed]

8. American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma Resources for Optimal care of the Injured Patient. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 1990. pp. 33–36.

9. Girotti MJ, Leslie K, Chinnick B, Holliday RL. Attitudes of surgical residents toward trauma care: A Canadian-based study. J of Trauma. 1994;36:101–105. [PubMed]

10. Richardson JD, Miller FB. Will future surgeons be interested in trauma care? Results of a resident survey. J Trauma. 1992;32:229. [PubMed]