| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Ursula Kelly, PhD, ANP-BC, PMHNP-BC | Emory University, Department of Family and Community Nursing, Atlanta VA Medical Center |

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

The purposes of this exploratory study were to a) describe physical health symptoms and diagnoses in abused immigrant Latinas, b) explore the relationships between the women’s physical health and their experiences of intimate partner violence (IPV), their history of childhood trauma and immigration status, and c) explore the correlations between their physical health, health-related quality of life (HRQOL), and mental health, specifically symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder (MDD).

Methods:

The convenience sample (n=33) for this cross-sectional descriptive study consisted of Latino women receiving emergency shelter and community-based services at a domestic violence services agency in the northeastern U.S. We used Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients to analyze the relationships between physical health variables and IPV type and severity, childhood and adulthood sexual abuse, and HRQOL.

Results:

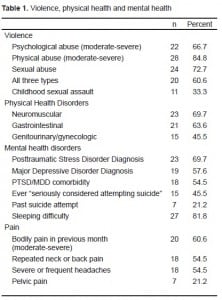

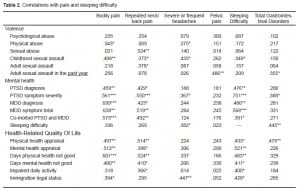

All of the women experienced threatened abuse. More than two-thirds experienced moderate to severe psychological abuse, moderate to severe physical abuse, and/or sexual abuse. Twenty women experienced all three types. Women endorsed one or more items in neuromuscular (69.7%), gastrointestinal (63.6%), and genitourinary/gynecologic (45.5%) groupings. Pain was the most reported symptom: bodily pain in previous month (60%), repeated neck or back pain (54.5%), severe/frequent headaches (54.5%), and pelvic pain (21.2%). Eighty-one percent of women endorsed at least one pain item (mean=2.56), and the same number reported difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep. Pain and sleeping difficulty, the two most frequently reported symptoms, were consistently and highly correlated with PTSD and MDD diagnoses and symptom severity and HRQOL. Childhood sexual abuse was significantly correlated with total pain symptoms (r=0.606, p=0.000) and difficulty sleeping (from the PTSD scale) (r=0.349, p=0.046). Both pain (r=0.400, p=0.023) and sleeping difficulty (r=0.467, p=0.006) were also strongly correlated with undocumented immigration status.

Conclusion:

Detailed assessment of patients with pain and sleep disorders can help identify IPV and its mental health sequelae, PTSD and MDD. Accurate identification of the root causes and pathways of the health burden carried by victims and survivors of IPV, who are vulnerable to persisting health problems without adequate healthcare, is critical in both clinical practice and research.

INTRODUCTION

Nearly one in four women have been physically assaulted or raped by an intimate partner in their lifetime.1, 2 When psychological abuse is included, the prevalence of lifetime intimate partner violence (IPV) approaches 50%.1,2 IPV is associated with multiple and overlapping health sequelae, which can result in significant and long-term health burdens. The most commonly cited include self-reported poor health, general chronic pain, headaches, gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, pelvic pain and infections, several mental health disorders, and health-risk behaviors.3–14

IPV-related negative health outcomes are likely magnified for abused immigrant Latinas who face multiple stressors, higher levels of social isolation and entrapment, and exacerbating cultural factors.15–19 Latinos in the U.S. remain a vulnerable population and continue to experience health disparities.20 As a group, Latinos are subject to health disparities and are disproportionately represented in socio-demographic groups with increased risk for both physical and mental health problems, creating a “double jeopardy” for abused Latinas.20–22

This exploratory study investigated the physical and mental health status and healthcare needs of immigrant Latinas who had experienced IPV. Our specific aims were to a) explore the relationships between the women’s physical health and their experiences of IPV, their history of childhood trauma and immigration status, and b) explore the correlations between their physical health, health-related quality of life (HRQOL), and mental health, specifically symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder (MDD). A full description of the study methods and the relationships between the women’s mental health and their IPV experiences, child sexual trauma, HRQOL, and immigration status was reported previously.16

Pain as a Health Effect of IPV

Pain is a prevalent consequence of IPV, both directly through physical injury and indirectly via other causal pathways. Wuest et al.23 found that PTSD symptom severity mediated the relationship between IPV and chronic pain. They also found that psychological IPV severity had a direct effect on chronic pain severity, while IPV-related physical assault had an indirect effect.23

Mental Health Effects of IPV

MDD, PTSD and anxiety are the most frequently diagnosed mental health problems related to IPV. Golding,24 who conducted a meta-analysis of the IPV-related research literature, reported that the weighted mean prevalence of PTSD was 63.8% (range 31%–84.4%), of major depression 47.6% (range 15%–83%), and of suicidality 17.7% (range 4.6%–77%). Most reports of the co-morbidity of IPV-related PTSD and MDD approach or exceed 50%.25–27 Available data suggest that PTSD and MDD are higher among Latinas who report IPV than African-American or white women.28

Health-Related Quality of Life

Recent data showed that 24.7% of Hispanics rated their general health as fair or poor versus 12.6% for whites.29 McGee et al.34 found that Hispanic women who rated their health as poor or fair, versus good, very good, or excellent had more than twice the odds of death. Abused Latina women have lower HRQOL than abused women of other ethnic groups.4–6,30–33

METHODS

Study Design

A cross-sectional mixed-methods design was used to gather descriptive data about the women’s IPV experiences, physical and mental health status, health services utilization and healthcare needs.

Sample

The convenience sample (n=33) consisted of Latino women who were receiving services at a domestic violence services agency in an urban area in New England. The mean age was 39.7 years (range 19–74 years). Two-thirds spoke no or minimal English and one in four were undocumented.

Procedure

Recruitment

Institutional review board approval was obtained from the principal investigator’s institution. Informed consent was obtained in writing and data de-identified. We obtained a National Institutes of Health Certificate of Confidentiality for additional protection of the participants’ confidentiality and personal information.

Data collection

Interviews were conducted in Spanish or English based on the participants’ choice. Bilingual study staff and interpreters were used as needed. The survey included validated Spanish translations of all instruments.

Variables and Their Measurement

Intimate partner violence

We used the Severity of Violence Against Women Scale (SVAWS) to assess the severity of IPV on two dimensions: a) threats, which are considered psychological abuse, and b) actual violence, which includes physical and sexual abuse (alpha coefficient 0.92).34

Childhood sexual assault

A single question was asked, “Were you ever sexually assaulted as a child?” For positive responses, women were asked to identify the assailant’s relationship to her.

Physical health

We assessed physical health using an instrument developed by Coker et al.,12 which is a modified version of the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).35 The instrument contains a review of multiple symptoms for every body system, including multiple recognized physical health consequences and symptoms of IPV.

Mental health

We used the PTSD Checklist-Civilian version (PCL-C)36 to assess for symptoms of PTSD (alpha coefficient =0.906). The PCL-C can be used as an indicator of symptom severity and to establish a diagnosis of PTSD. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the DSM-IV criteria for major depressive episode.37 We used both symptom totals and diagnoses of PTSD and MDD in data analyses.

Health-Related Quality of Life

Standard HRQOL items from the NHIS were used. Physical pain was included in the HRQOL items, as well as in the health status assessment questionnaire.

Data Analysis

We analyzed data using SPSS 17.0 for Windows. Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables. We used Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients to analyze the relationships between physical health variables and IPV type and severity, childhood and adulthood sexual abuse, immigration legal status and HRQOL.

RESULTS

The frequencies of IPV, childhood sexual assault, and the most common physical and mental health disorders reported are displayed in Table 1. Pain was the most reported symptom with all pain items taken into account. Sleeping difficulty was the single most commonly reported symptom. For both physical and mental health, more than half of the women reported that their health was poor or only fair. Ten women rated their health better than last year and 12 rated their health worse. The respondents’ past and current use of tobacco, alcohol and drugs was negligible.

Correlates of Physical Health

Correlations between physical health problems

We created composite variables (total number of endorsed items) for neuromuscular, gastrointestinal (GI), and genitourinary/gynecologic (GU/GYN) groups of symptoms and disorders. Total neuromuscular disorders and total GI disorders were highly correlated (r=0.644, p≤0.001). Singularly, repeated neck/back pain was highly correlated with one or more and total GI disorders (5=0.555, p≤0.001).

Correlations with violence, mental health, HRQOL, and immigration status

Pain and sleeping difficulty were consistently and highly correlated with various forms of IPV and sexual assault, PTSD, MDD, and HRQOL (Table 2). Sleep is included on both axes in Table 2 to illustrate the multiple interactions sleep has with overall health and well-being. GU/GYN problems were correlated with psychological abuse (r=0.455, p=0.011) and sexual assault in the previous year (r=0.403, p=0.024) but not with physical abuse. The composite variables within the neuromuscular, GI, and GU/GYN groups were not correlated with types of IPV and sexual assault.

DISCUSSION

The range and incidence of several common adverse physical outcomes of IPV found in this study were consistent with published reports, including high rates of neuromuscular and functional GI disorders.6,11 The rates of PTSD and MDD in this study were similar to those reported in domestic violence shelter-based studies and higher than those reported in population-based studies. Substance abuse is strongly correlated with IPV; however, it was nearly absent in this sample.5,38

Pain and sleeping difficulty emerged as the most problematic health effects and the mostly strongly correlated with nearly every violence, mental health, and HRQOL dimension analyzed. Pain and sleeping difficulty are not easily located in the false dichotomy of physical and mental health adverse health effects of IPV, nor do they fit into discrete clinical diagnostic boxes. As such, they perfectly illustrate the complex, intertwined and nuanced effects of IPV and other interpersonal trauma on the lives of women. Both pain and sleep are significant contributors to quality of life and overall functioning. PTSD has been shown to strongly mediate the relationship between trauma and health status and functioning.39 In this study, pain was more strongly correlated with PTSD and MDD than with IPV and sexual assault.

LIMITATIONS

This study addresses a gap in the literature regarding the physical health sequelae of IPV in Latinas and the associations of these sequelae with mental health and quality of life. Given the small sample size, the results should be considered exploratory and not generalizable. This sample of Latinas who have sought help for IPV may vary from other Latinas or from abused women who do not seek services.

CONCLUSION

Although this study was exploratory, these results have important implications for research and clinical practice, particularly in emergency settings where pain is a common presenting complaint. Detailed assessment of patients with pain and sleep disorders can help identify IPV and its mental health sequelae, particularly PTSD and MDD. Accurate identification of the root causes and pathways of the health burden carried by victims and survivors of IPV, who are vulnerable to persisting health problems without adequate healthcare, is critical in both clinical practice and research.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Monica H. Swahn, PhD

Submission history: Submitted March 3, 2010; Revision Received April 14, 2010; Accepted May 2, 2010

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Ursula Kelly, PhD, ANP-BC, PMHNP-BC, Emory University, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Department of Family and Community Nursing, 1520 Clifton Rd. NE, Atlanta, GA, 30322

Email: ukelly@emory.edu

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. This study was supported in part by grant R49/CCR 522339 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

REFERENCES

1. Krug EG, Dahlberg JA, Mercy JA, et al. World report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002.

2. Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full report of the prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice; 2000.

3. Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Chronic disease and health risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violence – 18 US states/territories, 2005. Ann of Epid. 2008 Jul;18(7):538–44.

4. Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Reid RJ, et al. Medical and psychosocial diagnoses in women with a history of intimate partner violence. Arch of Inter Med. 2009;169(18):1692–7.

5. Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am J of Prev Med. 2002;23(4):260–8. [PubMed]

6. Wuest J, Merritt-Gray M, Ford-Gilboe M, et al. Chronic pain in women survivors of intimate partner violence. J of Pain. 2008;9(11):1049–57. [PubMed]

7. Carbone-Lopez K, Kruttschnitt C, Macmillan R. Patterns of intimate partner violence and their associations with physical health, psychological distress, and substance use. Pub Heal Rep.2006;121(4):382–92.

8. Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Cannon EA, et al. Intimate partner violence in latina and non-latina women. Am J of Pre Med. 2009;36(1):43–8.e41.

9. Coker AL. Does physical intimate partner violence affect sexual health? A systematic review. Trau Vio Abus. 2007;8(2):149–77.

10. Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359(9314):1331–6. [PubMed]

11. Leserman J, Drossman DA. Relationship of abuse history to functional gastrointestinal disorders and symptoms – Some possible mediating mechanisms. Trau Vio Abus. 2007;8(3):331–43.

12. Coker AL, Smith PH, Bethea L, et al. Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Arch of Fam Med. 2000;9(5):451–7. [PubMed]

13. Tomasulo GC, McNamara JR. The relationship of abuse to women’s health status and health habits. J of Fam Vio. 2007;22(4):231–5.

14. Ellsberg M, Jansen H, Heise L, et al. Hlth WHOMSW Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet. 2008;371(9619):1165–72. [PubMed]

15. Kelly UA. “What will happen if I tell you?” Battered Latina women’s experiences of healthcare.Can J of Nur Res. 2006;38(4):78–95.

16. Kelly UA. Symptoms of PTSD and major depression in Latinas who have experienced intimate partner violence. Iss in Men Heal Nur. 2010;31:119–127.

17. Ramos BM, Carlson BE. Lifetime abuse and mental health distress among English-speaking Latinas. Affilia J of Women and Soc Work. 2004;19(3):239–56.

18. Rodriguez M, Valentine JM, Son JB, et al. Intimate partner violence and barriers to mental health care for ethnically diverse populations of women. Trau Viol & Abuse. 2009;10(4):358–74.

19. Rodrìguez MA, Heilemann MV, Fielder E, et al. Intimate partner violence, depression, and PTSD among pregnant Latina women. Ann of Fam Med. 2008;6(1):44–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

20. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

21. Centers for Disease Control Access to Health-Care and Preventive Services Among Hispanics and Non-Hispanics – United States, 2001–2002. MMWR. 2004;53(40):937–41. [PubMed]

22. Centers for Disease Control Health Disparities Experienced by Hispanics – United States. MMWR.2004;53(40):935–7. [PubMed]

23. Wuest J, Ford-Gilboe M, Merritt-Gray M, et al. Abuse-related injury and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder as mechanisms of chronic pain in survivors of intimate partner violence. Pain Med. 2009;10(4):739–47. [PubMed]

24. Golding JM. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. J of Fam Vio. 1999;14(2):99–132.

25. Fedovskiy K, Higgins S, Paranjape A. Intimate partner violence: How does it impact major depressive disorder and post traumatic stress disorder among immigrant latinas? J of Imm and Mino Heal. 2008;10:45–51.

26. Stein MB, Kennedy C. Major depressive and post-traumatic stress disorder comorbidity in female victims of intimate partner violence. J of Aff Dis. 2001;66(2–3):133–138.

27. Nixon RDV, Resick PA, Nishith P. An exploration of comorbid depression among female victims of intimate partner violence with posttraumatic stress disorder. J of Aff Dis. 2004;82:315–20.

28. Caetano R, Cunradi C. Intimate partner violence and depression among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. Ann of Epid. 2003;13(10):661–5.

29. Chowdhury PP, Balluz L, Strine TW. Health-related quality of life among minority populations in the United States, BRFSS 2001–2002. Ethn and Dis. 2008;18:483–7.

30. Lown EA, Vega WA. Intimate partner violence and health: self-assessed health, chronic health, and somatic symptoms among Mexican-American women. Psych Med. 2001;63(3):352–60.

31. Denham AC, Frasier PY, Hooten EG, et al. Intimate partner violence among latinas in eastern North Carolina. Viol against Women. 2007;13(2):123–40.

32. Alsaker K, Moen BE, Nortvedt MW, et al. Low health-related quality of life among abused women.Qual of Life Res. 2006;15(6):959–65. [PubMed]

33. Lown EA, Vega WA. Prevalence and predictors of physical partner abuse among Mexican American women. Am J of Pub Heal. 2001;91(3):441–5.

34. Marshall L. Development of the severity of violence against women scale. J of Fam Viol.1992;7:103–21.

35. Census UBot . National Health Interview Survey Field Representative’s Manual. In: Service UPH, editor. Washington, D.C.: 1994.

36. Weathers F, Litz B, Herman D, et al. Ann Conven of the Intern Soc for Trau Str Stud. San Antonio, TX: 2003. The PTSD checklist (PCL): reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility.

37. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-IV-TR. 4th, Text Revision ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

38. González-Guarda RM, Peragallo N, Urrutia MT, et al. HIV risks, substance abuse, and intimate partner violence among Hispanic women and their intimate partners. J of the Assoc of Nur in AIDS Care. 2007;19(4):252–66.

39. Green BL, Kimberling R. Trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder, and health status. In: Schnurr PP, Green BL, editors. Trau and heal: Physical health consequences of exposure to extreme stress.Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. pp. 13–42.