| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Ashley Stone, MPH | California Hospital Association, Sacramento, California University of California, Davis Public Health Sciences, Davis, California |

| Debby Rogers, RN, MS | California Hospital Association, Sacramento, California |

| Sheree Kruckenberg, MPA | California Hospital Association, Sacramento, California |

| Alexis Lieser, MD | California American College of Emergency Physicians, Sacramento, California |

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

This is an observational study of emergency departments (ED) in California to identify factors related to the magnitude of ED utilization by patients with mental health needs.

Methods:

In 2010, an online survey was administered to ED directors in California querying them about factors related to the evaluation, timeliness to appropriate psychiatric treatment, and disposition of patients presenting to EDs with psychiatric complaints.

Results:

One hundred twenty-three ED directors from 42 of California’s 58 counties responded to the survey. The mean number of hours it took for psychiatric evaluations to be completed in the ED, from the time referral was placed to completed evaluation, was 5.97 hours (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.82–7.13). The average wait time for adult patients with a primary psychiatric diagnosis in the ED, once the decision to admit was made until placement into an inpatient psychiatric bed or transfer to an appropriate level of care, was 10.05 hours (95% CI, 8.69–11.52). The average wait time for pediatric patients with a primary psychiatric diagnosis was 12.97 hours (95% CI, 11.16–14.77). The most common reason reported for extended ED stays for this patient population was lack of inpatient psychiatric beds.

Conclusion:

The extraordinary wait times for patients with mental illness in the ED, as well as the lack of resources available to EDs for effectively treating and appropriately placing these patients, indicate the existence of a mental health system in California that prevents patients in acute need of psychiatric treatment from getting it at the right time, in the right place.

INTRODUCTION

California’s mental healthcare delivery system—decentralized, underresourced, and disorganized—has recklessly collided with emergency medicine. Decades of cuts to local and state-funded mental health programs have led to an increased dependence on hospital emergency departments (ED) without corresponding resources.1 The ED has become the only safety net provider for many patients with unmet mental health care needs in California.2

In the United States, about 1 in 4 adults suffers from a diagnosable mental disorder, and between 5% and 7% of adults suffer from a severe mental illness (SMI).3 The California Department of Mental Health estimated in 2007 that there were nearly 2 million people in the state of California in need of mental health services for an SMI.4 Mental illness, a leading cause of disability and suicide, carries huge social, economic, and personal costs.5,6 Despite the awareness that mental illness poses a formidable burden for individuals, families, government payers, policy makers, and healthcare providers, the public health impact of mental illness remains severely underrecognized and underfunded.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the process of deinstitutionalization—the movement that shifted patients with mental illness from state hospitals to community-based care—transformed California’s mental healthcare delivery system. Bachrach7 describes deinstitutionalization as a process involving 2 primary elements: “(1) the eschewal of traditional institutional settings—primarily State hospitals—for the care of the mentally ill; and (2) the concurrent expansion of community-based services for the treatment of these individuals.” The process was aided by the passage of the Lanterman-Petris-Short (LPS) Act, signed into law by Governor Ronald Reagan in 1967, which significantly reduced involuntary commitment of individuals with mental illness to state hospitals.8 To be involuntarily committed or treated under the LPS Act, patients had to meet imminent dangerousness criteria that effectively ended inpatient care for individuals with mental illness who met less rigid “need-for-hospitalization” criteria.9

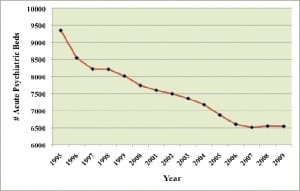

The LPS Act accomplished what it set out to do: within 2 years of implementation, the number of state hospital patients decreased from 18,831 to 12,671, and by 1973, there were 7,000 patients in just 5 state institutions.10 There was also a corresponding drop in the number of inpatient psychiatric beds in private hospitals. Between 1995 and 2009, there was a 30% loss of psychiatric beds (Figure 1). Currently, 30 of California’s 58 counties lack inpatient psychiatric beds.11 Many patients discharged from the state institutions, faced with inadequate care in their communities, became homeless or were put into “boarding houses” that offered little by way of psychiatric treatment.2,10,12 Many discharged patients also found themselves incarcerated in the criminal justice system.13,14 California in particular treats more individuals with mental illness in prison than outside of it; the Los Angeles county jail system has been called the largest mental health institution in the entire country.15,16

The promise of adequate and sustainable community-based care was unrealized, leading to a “revolving door” of homelessness, hospitalization, and incarceration for many individuals faced with debilitating mental illnesses in a fragmented system that does not provide appropriate levels of care when they are needed.17 The Bronzan-McCorquodale Act of 1991, or program realignment, decentralized California’s mental health system by shifting authority for mental health service delivery from the state to the counties. One of the intentions of realignment was to provide secure funding for community-based mental health services.12 However, the contribution to counties from the state general fund has been determined more by history and politics than by the needs of counties for mental health funding. Program realignment legislation led to identification of recommended mental health services, but it was a guideline rather than a mandate with associated sanctions for not implementing community-based services.18 Realignment funds have also not kept pace with population growth or inflation and have been negatively impacted by the economic downturn.

When mental health services and supports are unavailable or poorly coordinated, patients with unmet mental health needs turn to the ED for care.2,19 In the current healthcare delivery system, EDs are the only institutional providers required by Federal law to evaluate anyone seeking care.20 The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act requires that all hospital EDs medically screen all patients seeking care in the ED—including evaluation and stabilization of patients suffering from mental illness.21 In 2007, there were 10.1 million ED visits in California. More than 324,000 of these visits—3.2%—were by patients with a psychiatric diagnosis.22 Research has shown a disproportionate increase in mental health–related ED visits, in comparison to ED visits in general. Between 1992 and 2001, the number of documented mental health–related ED visits increased by 38%, compared to an 8% increase in overall ED usage.23

This system of delivering nonemergent mental healthcare in the ED leads to inappropriate and inadequate patient care, issues with patient and staff safety, and overall decreased ED capacity.1,2There is a great need to reduce this reliance on EDs and identify more appropriate treatment options.Healthy People 2020 identified the overarching goal for mental health and mental disorders as follows: “Improve mental health through prevention and by ensuring access to appropriate, quality mental health services.”24 Improving mental healthcare necessitates an understanding of how history, policy, institutions (including EDs), providers, and patients currently interact in the mental healthcare delivery system. This study evaluated a small subset of these interactions in California EDs, focusing on the patients they serve who present with psychiatric issues.

METHODS

Survey Development

The objective of the survey was to identify and quantify variables related to the magnitude of emergency and nonemergent ED utilization by patients with mental health needs by surveying hospital ED directors. The survey addressed the variables leading to prolonged ED stays, the wait times to obtain a psychiatric evaluation and placement wait times, the concerns of staff that treat this patient group, and the external resources available to support the EDs when caring for these patients. This survey updated a 2006 survey, Impact of Psychiatric Patients on Emergency Departments,25 which found that the reliance on EDs to provide care for patients with mental illness who have nonemergent physical or mental health needs creates undue strain on hospitals and their staff; moreover, it delays needed treatment for these individuals, since it takes significant amounts of time to appropriately evaluate and place patients in need of inpatient psychiatric care.

Survey Administration

To maximize response rates, the survey was administered through an online survey tool, which allowed embedded logic redirecting respondents, based on their responses. Using a member database of hospitals in California, a link to the survey was sent to all 259 ED directors at member hospitals with emergency rooms. There were an additional 68 member EDs without valid contact information for the ED directors; for each of these hospitals, a request was sent to the chief executive officer to forward to the current ED director. Of California’s 58 counties, 55 have hospitals that are California Hospital Association members and have an ED.

Survey Analysis

Mean wait times were calculated from survey questions pertaining to length of wait times for evaluation, treatment, and disposition of patients in the ED. To check for statistically significant differences in median wait times, we conducted a Kruskal-Wallis test of the equality of medians for 2 or more populations. The Kruskal-Wallis test does not require that the data be normal, but instead uses the rank of the data values rather than the actual data values for the analysis.26 Since the study data exhibit nonnormality, Kruskal-Wallis test is an appropriate choice.

RESULTS

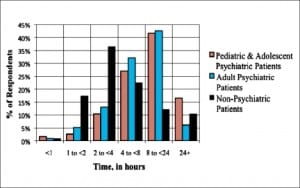

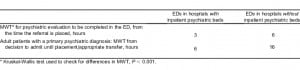

In total, there were 123 respondents (response rate of 37.6%). The responses came from hospitals in 42 counties—76% of California counties with EDs. About a quarter of respondents (n = 33) indicated their hospitals have inpatient psychiatric beds, with 87.9% of these hospitals (n = 29) having inpatient beds designated for involuntary treatment. The mean wait time for psychiatric evaluation and placement determination in the ED, from the time the referral for evaluation (eg, psychiatric consult) is placed until completed evaluation, was 5.97 hours (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.82–7.13). The average wait time for adult patients with a primary psychiatric diagnosis in the ED, once the decision to admit has been made until placement into an inpatient psychiatric bed or transfer to an appropriate level of care, was 10.05 hours (95% CI, 8.6–11.52). The average wait time for pediatric patients with a primary psychiatric diagnosis was 12.97 hours (95% CI, 11.16–14.77). These average wait times exceeded those for nonpsychiatric patients in the ED, which was 7.10 hours (95% CI, 5.55–8.65) (Figure 2). Although data were not collected on total length of stay in the ED, these data suggest a total length of stay for psychiatric patients—from request for psychiatric evaluation to admission or transfer—of more than 16 hours for adults and 19 hours for children and adolescents. For several time points, hospitals with inpatient psychiatric beds had statistically significantly lower median wait times than those without inpatient psychiatric beds (Table 1).

About one third of ED directors indicated that their hospital operates a psychiatric evaluation team; 81% of the hospital psychiatric evaluation teams are available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The mean response time for hospital psychiatric emergency teams to evaluate patients in the ED was 1.61 hours (95% CI, l.29–1.93). More than 60% of ED directors indicated that their county operates a psychiatric evaluation team, with 71% of the county teams available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The mean response time for county psychiatric evaluation teams was 4.82 hours (95% CI, 4.04–5.59). Twenty percent of ED directors indicated that a private company operates a psychiatric evaluation team, with 86% of the private teams available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The mean response time for private teams to evaluate patients in the ED was 4.36 hours (95% CI, 3.09–5.64). Greater than 30% of hospitals reported not having access to a psychiatric evaluation team 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Less than half of ED directors reported using or having access to community and county mental health resources to assist patients with mental health issues. On average, ED directors reported that 42% of patients presenting in their EDs with a behavioral health issue could have been adequately cared for at a nonemergency level of care (95% CI, 38%–47%).

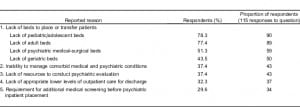

“Lack of beds” was overwhelmingly the most common reason for extended ED stays in this patient population. Specifically, 78.3% of ED directors (n = 90) cited lack of pediatric/adolescent psychiatric inpatient beds as the most common reason, followed closely by adult psychiatric inpatient beds (77.4%; n = 89). The 5 most common reported reasons for extended stays, as well as the percentage and proportion of respondents for each category, are presented in Table 2.

Open-ended questions were asked to allow respondents to express concerns not captured in the other survey questions. Comments included the following:

- Limited psychiatric evaluation team availability and resources after hours

- Problems with bed availability and disposition after psychiatric evaluation

- Nondesignated facilities cannot hold patients involuntarily after 24 hours

- Psychiatric evaluation teams will not come to evaluate a patient unless there is a bed available for the patient

- Shortage of medical-psychiatric beds for patients who require both mental health treatment and ongoing medical treatment

- Staffing/funding cut significantly in the last few years, leading to longer wait times for evaluation and placement

- Difficulty placing geriatric psychiatric patients

- Difficulty placing pregnant psychiatric patients

- Physical problem of getting an evaluation team to the ED because of geographic location

- Often evaluators will try and release patients who are a danger to themselves by commenting that “it is not against the law to be insane”

- County has to pay for anyone it hospitalizes; therefore, to make its funding stretch, it tries to not hospitalize anyone

- Closest facility that will take patients is an 8-hour drive away

- It is a fight to get our psychiatric patients the care they need

DISCUSSION

Mental illness poses a significant public health burden in California as well as nationally. In market economies such as the United States, the burden of disability associated with mental illness is at the same level as that of heart disease and cancer. Mental disorders lead to suicide, decreased quality of life for those who suffer from them, and enormous costs for the public health system.21 Yet, mental health services and programs continue to be reduced as more patients need them. In 2010, former Governor Schwarzenegger announced a 60% cut in funding for community mental health programs, which will further ensure that the supply of mental health services does not meet the demand.27

The results of the survey indicate a mental healthcare delivery system in crisis—one with a high demand and decreasing supply of inpatient psychiatric beds. In one large county, ED directors reported that psychiatric evaluation teams would not come to evaluate patients in the ED if there are no inpatient psychiatric beds available to place patients, further delaying definitive treatment. Because patients have trouble accessing services in the community—including medication management and therapy—they use the ED for basic and intermediate care.1 Our current mental health system still suffers from, and is largely a reflection of, the poor transition from state institutions to community-based treatment and the lack of local funding.

While perhaps well intentioned, the LPS Act has fostered a mental health system that requires seriously ill individuals to deteriorate to dangerousness or grave disability before they can receive needed treatment. The LPS Act gives authority to detain and transport to law enforcement, attending staff, or other persons designated by the county. Those designated may, “upon probable cause, take, or cause to be taken, the person into custody and place him or her in a facility designated by the county and approved by the State Department of Mental Health as a facility for 72-hour treatment and evaluation.”28 “LPS-designated facility” is not defined in statute, and while only such facilities can detain a person under 5150 statute, hospital EDs in nondesignated facilities still provide care for patients who may meet the criteria for an involuntary hold—some for more than 24 hours. Nondesignated EDs are thus often forced to choose between releasing a potentially dangerous patient and violating patient rights by involuntarily detaining patients beyond what is legally allowed by law.

Many ED directors reported that a significant portion of the psychiatric patients presenting in the ED could have been best cared in the outpatient setting. ED usage for needs such as an adjustment in psychiatric medication is symptomatic of both a suffering mental health system and a broader healthcare system in which access to care is not guaranteed.1,2 According to the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, only 12.9% of all ED visits in the United States in 2006 were classified as emergent.29 When the ED is not used for true acute care services and emergencies because patients do not have access to outpatient services to manage their disease process, there can be serious consequences, such as patients’ needs not always fully met, patients enduring long wait times, and staff burnout.30 Despite these recognized threats to patients and staff, the mental health delivery system has deteriorated to a point where the only choice of care for patients with mental illness is very often the ED. The Council on Medical Service described the influx of patients seeking psychiatric care in the ED as a “symptom of a larger systemic problem…. The crumbling infrastructure of the mental health system is an example of what could happen in other areas of medicine if not properly financed according to the needs of the population.”1

Frank Lanterman, an author of the LPS Act, said in the early 1980s, “I wanted the LPS Act to help the mentally ill. I never meant for it to prevent those who need care from receiving it. The law has to be changed.”31 The LPS Act, signed in 1967, remains unchanged, and the community-based services promised by deinstitutionalization never materialized. Consequently, the ED has become a way station for patients stuck in a mental health system in desperate need of transformation.

LIMITATIONS

This study has some notable limitations. First, we cannot verify that the information obtained from ED directors was completely based on actual data. Rather, the 123 survey responses from ED directors represent both data-based and anecdotal accounts of the experiences of individual hospital EDs in treating patients suffering with psychiatric disorders. Secondly, many of the questions forced respondents to select answers representing ranges of values (eg, “1 to less than 4 hours”), thus sacrificing precision in responses and subsequent analysis. Despite these limitations, the study’s broad representation of most California counties renders the results an important addition to the literature on EDs and psychiatric services in California.

CONCLUSION

The current mental health system—fostered in large part by the LPS Act and the decades-long prioritization of deinstitutionalization—provides no room for prevention and, as indicated by the results of this study, leads to long ED visits for patients suffering from mental illness. This population experiences wait times far exceeding those of patients presenting in the ED for physical health problems. This system is failing both patients, who suffer from debilitating mental illnesses, and healthcare providers, who are ill prepared and underresourced to meet the increasing demand of patients with unmet mental health care needs. Individuals suffering from mental illnesses deserve treatment in the right place, at the right time.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Leslie Zun, MD

Submission history: Submitted February 17, 2011; Revision received May 9, 2011; Accepted June 22, 2011

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

DOI: 10.5811/westjem.2011.6.6732

Address for Correspondence: Debby Rogers, RN, MS

California Hospital Association, 1215 K St, Ste 800, Sacramento, CA 95814

E-mail: drogers@calhospital.org

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding, sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Tuttle GA. Report of the Council on Medical Service, American Medical Association: Access to psychiatric beds and impact on emergency medicine. CMS report 2-A-08. American Medical Association Web site. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/372/a-08cms2.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2010.

2. Alakeson V, Pande N, Ludwig M. A plan to reduce emergency room “boarding” of psychiatric patients. Health Aff. 2010;29:1637–1642. [PubMed]

3. National Institute of Mental Health; 2010. NIMH statistics. Available at:http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/statistics/index.shtml. Accessed October 1.

4. California Department of Mental Health. Statistics & data analysis: prevalence rates of mental disorders (statewide) 2010. Available at:http://www.dmh.ca.gov/Statistics_and_Data_Analysis/docs/Population_by_County/California.pdf. Accessed September 20.

5. California Department of Mental Health; 2004. Mental Health Services Act.

6. James DJ, Glaze LE. Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report: Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice: 2006.

7. Bachrach L. Deinstitutionalization: An Analytical Review and Sociological Perspective.Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, & Welfare, National Institute of Mental Health;; 1976. DHEW Publication No. 76-351.

8. Langsley D, Barter J. Community mental health in California. West J Med. 1975;122:271.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

9. Abramson MF. The criminalization of mentally disordered behavior: possible side-effect of a new mental health law. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1972;23:101–105. [PubMed]

10. Torrey E. The Insanity Offense: How America’s Failure to Treat the Seriously Mentally Ill Endangers Its Citizens. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company;; 2008.

11. California Hospital Association, Office of Statewide Health Planning & Development. Acute psychiatric inpatient beds closures/downsizing. 2011. Available at:http://www.calhospital.org/PsychBedData. Accessed January 21.

12. California Association of Local Mental Health Boards and Commissions/Eli Lilly; 2008. California Association of Local Mental Health Boards and Commissions. Navigating the currents: a guide to California’s public mental health system. Available. at: http://www.namicalifornia.org/document-detail.aspx?page=homepage&tabb= hometabb&part=director&lang=ENG&idno=3941. Accessed January 21, 2011.

13. Lamb HR, Grant RW. The metally ill in an urban county jail. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:17–22. [PubMed]

14. Lamb HR, Weinberger LE. Persons with severe mental illness in jails and prisons: a review. New Dir Ment Health Serv. 2001. pp. 29–49. [PubMed]

15. 2010. Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. Correctional services division. Jail Mental Heath Services Correctional Services Division Web site. Available at: http://la-sheriff.org/divisions/correctional/mh/index.html. Accessed June 5.

16. Bal WD. Mentally ill prisoners in the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation: strategies for improving treatment and reducing recidivism. J Contemp Health Law Policy.2007;24:1–42. [PubMed]

17. Baillargeon J, Binswanger IA, Penn JV, et al. Psychiatric disorders and repeat incarcerations: the revolving prison door. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:103–109. [PubMed]

18. Masland M. The political development of “Program Realignment”: California’s 1991 mental health care reform. J Behav Health Serv Res. 1996;23:170–179. [PubMed]

19. Brown J. A survey of emergency department psychiatric services. Gen Hosp Psychiatry.2007;29:475–480. [PubMed]

20. Josiah M. The role of emergency medicine in the future of American medical care. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:230–233. [PubMed]

21. Department of Health & Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Washington, DC: United States Department of Health & Human Services; 2000. Mental health and mental disorders; pp. 18.1–18.32.

22. Williams M, Pfeffer M, Hilty D. Telepsychiatry in the emergency department. California HealthCare Foundation. 2009.

23. Larkin GL, Claassen CA, Emond JA, et al. Trends in U.S. emergency department visits for mental health conditions, 1992 to 2001. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:671–677. [PubMed]

24. Department of Health & Human Services. Healthy people 2020: mental health and mental disorders. 2011. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=28. Accessed January 10.

25. Kruckenberg S, Rogers D. California Hospital Association Survey: Impact of Psychiatric Patients on Emergency Departments. Sacramento, CA: 2006.

26. Siegel S, Castellan NJ. Nonparametric Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;; 1988.

27. Schwarzenegger A. Speech: Governor Schwarzenegger unveils 2010–11 revised state budget proposal. Office of California Governor Web site. 2010. Available at:http://gov.ca.gov/speech/15164/. Accessed May 22.

28. CA State Legislature. Lanterman-Petris-Short Act. Legislative Counsel State of California, Welfare & Institutions Code 5000–5157. Available at: http://leginfo.ca.gov1967. Accessed January 2, 2011.

29. McCaig LF, Nawar EW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2004 Emergency Department Summary. Advance Data From Vital and Health Statistcs; No. 372. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics;; 2006.

30. Brim C. A descriptive analysis of the non-urgent use of emergency departments. Nurse Res.2008;15:72–88. [PubMed]

31. Dewees E. Los Angeles Times. 1987. Legislation for the mentally ill [letter to the editor] December 5.