| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Bing Pao, MD | University of California, San Diego, California |

| Myles Riner, MD | MedAmerica, Inc., Emeryville, California |

| Theodore C. Chan, MD | University of California, San Diego, California |

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

ABSTRACT

Introduction

The objective of this study was to examine reimbursement trends for emergency provider professional services following the balance billing ban in California.

Methods

We conducted a blinded web-based survey to collect claims data from emergency providers and billing companies. Members of the California Chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians (California ACEP) reimbursement committee were invited to participate in the survey. We used a convenience sample of claims to determine payment rates before and after the balance billing ban.

Results

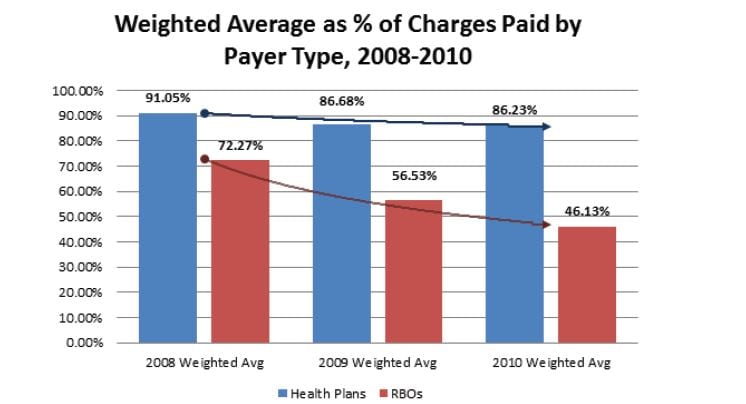

We examined a total of 55,243 claims to determine the percentage of charges paid before and after the balance billing ban took effect on October 15, 2008. The overall reduction in percentage of charges paid was 13% in the first year and 19% in the second year following the balance billing ban. The average percentage of charges paid by health plans decreased from 91% to 86% from 2008 to 2010. Payments by risk-bearing organizations decreased from 72% to 46% of charges during the same time frame.

Conclusion

Payment rates by subcontracted risk-bearing organizations for non-contracted emergency department professional services declined significantly following the balanced billing ban whereas payment rates by health plans remained relatively stable.

INTRODUCTION

Many health plans offer health insurance through health maintenance organizations (HMOs) that in turn provide medical services to enrollees through contracted provider networks. According to a 2011 report by the Kaiser Foundation, almost 16 million Californians were enrolled in HMOs.1 In California, HMOs are regulated by the Department of Managed Health Care (DMHC). California and a few other states allow health plans to delegate financial responsibility for payment of emergency providers’ claims to risk-bearing organizations (RBOs). RBOs are usually medical foundations, medical groups or independent physician organizations that receive fixed periodic payments from health plans.2 In return, the RBO is responsible for providing healthcare services to health plan enrollees. In California, when a HMO patient receives out-of-network emergency care services, health plans or the delegated RBOs are obligated to pay the non-contracted provider directly for the emergency care rendered.3 HMO enrollees may receive out-of-network emergency services when the enrollee goes to the nearest out-of-network emergency department (ED) or when the emergency provider in an in-network hospital is not contracted with the health plan.

Payment disputes often occur when the health plan or RBO submits payment that is below the billed amount that a non-contracted provider considers reasonable for the service. To recoup the difference, emergency providers in many states “balance bill” the patient to recover the total amount owed to the provider. According to a 2007 study sponsored by the California Association of Health Plans, over a 2-year period more than 1.76 million insured Californians received balance bills following an ED visit.4 Several states prohibit emergency providers from balance billing patients for out-of-network services.5 Some states, such as Maryland, establish payment standards whereas other states do not specifically establish payment rates.5 On October 15,2008, the California DMHC issued regulations that defined balance billing as an unfair billing practice when HMOs and certain Knox-Keene regulated PPO plans insure the enrollee.6 The regulation was intended to leave patients out of billing disputes between the health plans and providers.7 The California Chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians (California ACEP) argued that the DMHC did not have jurisdiction to prohibit non-contracting emergency physicians (EP) from balance billing patients.8 On January 9,2009, the California Supreme Court issued an opinion regarding the legality of balance billing. In this landmark decision involving Prospect Medical Group versus Northridge Emergency Medical Group, the California Supreme Court ruled that emergency providers may not balance bill patients enrolled in Knox-Keene regulated health plans including HMOs and some preferred provider organizations (PPOs) that are regulated by the Department of Managed Health Care.9,10 The ruling does not apply to health plans that are not regulated by the DMHC, such as Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) plans and most PPOs. The Prospect decision did not determine the amount that the non-contracted provider should be paid, only that out-of-network providers “are entitled to reasonable payment for emergency services rendered to HMO patients.”9

Following the balance billing ban that took effect on October 15, 2008, emergency providers were concerned that Knox-Keene-regulated health plans and their delegated payers would have the unfettered ability to unilaterally decide the amount paid for emergency services. California ACEP conducted a survey to determine the impact of the balance billing ban on EPs.

METHODS

This study was funded by a public policy grant from the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP). California ACEP conducted a blinded web-based survey in 2012 to determine the impact of the balance billing ban on payments for non-contracted commercial claims. Members of the California ACEP reimbursement committee were asked to participate in the study. Committee members represented over 20 different physician groups or billing companies. Individuals, groups or billing companies representing several groups were allowed to submit claims data. The survey asked EPs or billing companies to report specified claims payment data (Table 1). We obtained a convenience sample of EP and billing companies’ claims data to perform the analysis. Any partially completed survey results were included in the analysis. The claims examined included only non-contracted commercial claims for health plans and RBOs regulated by the DMHC. We derived the selection of payers examined in the survey from the DMHC website listing of RBOs and Knox-Keene licensed health plans.10,11 The survey asked for the percentage of charges paid from June-August 2008, before the balance billing ban took effect, and the same months in 2009 and 2010, after the balance billing ban took effect on October 15, 2008. We determined the average percentage of charges paid by aggregating all of the claims for a payer and dividing the sum of the percentages by the number of claims.

Table 1. Balance billing survey questions.

| Average percentage of billed charges allowed:For each non-contracted Knox-Keene plan your practice deals with of significant volume, please calculate the average percentage of billed charges that plan ‘allowed,’ after all non-legal dispute efforts have been exhausted (closed commercial non-contracted claims only). (e.g., If a plan on average allowed $60 on $100 billed charges, the average percentage of billed charges allowed is 60%.) |

RESULTS

A total of 55,243 claims were available for analysis to determine the percentage of charges paid before and after the balance billing ban (Table 2). Data were available for 12 of 54 health plans listed on the DMHC website and 114 of 291 RBOs. The overall reduction in percentage of charges paid from 2008 to 2010 was 19%. The average percentage of charges paid by health plans from 2008 to 2010 decreased from 91% to 86%. RBOs demonstrated a more dramatic decrease in payment (from 72% to 46% of charges) during the same time frame (Figure).

Table 2. Percentage of charges paid before (2008) and after the balance billing ban (2009 & 2010).

| Payer category | Number of claims before balance billing ban (2008) | Percentage of charges paid before balance billing ban (2008) | Number of claims after balance billing ban (2009) | Percentage of charges paid after balance billing ban (2009) | Number of claims after balance billing ban (2010) | Percentage of charges paid after balance billing ban (2010) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health plans | 9,101 | 91.05% | 7,557 | 86.68% | 6,528 | 86.23% |

| RBO | 10,100 | 72.03% | 11,517 | 56.36% | 10,440 | 46.13% |

| Total | 19,201 | 81.04% | 19,074 | 68.37% | 16,968 | 61.56% |

RBO, risk bearing organizations

DISCUSSION

Health plans are required by California law to reimburse emergency providers directly for the reasonable and customary value of emergency services the provider rendered to the health plan’s enrollee.3 Under DMHC regulations, health plans are required to pay a reasonable amount based on a statistically credible database of usual and customary charges that is adjusted annually.12 Payment must also take the following factors into consideration, which are collectively known as the Gould criteria:12,13

The provider’s training, qualification, and length of time in practice;

The nature of the services provided;

The fees usually charged by the provider;

Prevailing provider rates in the general geographic area in which the services were rendered;

Other aspects of the economics of the medical provider’s practice that are relevant; and

Any unusual circumstances in the case.

This study examined the impact of the balance billing ban on emergency providers. Following the balance billing ban, our study indicates that emergency providers did experience a significant decline in percentage of charges by RBOs, whereas percentage of charges paid by health plans remained relatively stable. Data on many health plans were not available, which may be due to the possibility that these health plans were able to secure contracts with most emergency care providers. As a result, the contracted providers would not have any non-contracted claims data to submit to the survey.

Part of the percentage decline could be due to increases in the providers’ fee schedules. However, health plans and RBOs are required to adjust payments annually based on a statistically credible database of provider charges, which should mitigate the impact of changes in usual and customary charges on the percentage of charges paid. Health plans, in general, appear to reimburse claims at higher rates and adhered to the Gould criteria more frequently than RBOs.

One possibility for the payment discrepancy is the stricter enforcement of the Gould criteria upon health plans compared to RBOs. For example, in 2005 the DMHC fined Health Net for underpaying emergency care providers.14 In 2010, the DMHC fined the 7 largest health plans in California for underpaying or incorrectly paying physician claims.15 Through legal action, the DMHC established statutory authority and regulatory jurisdiction over RBOs and previously issued a cease-and-desist order against a RBO for the underpayment of non-contracted provider claims.16 However, a review of the DMHC enforcement actions has not revealed any fines against an RBO for underpayment of emergency provider claims.17 A second possibility for closer adherence to the Gould criteria by health plans is the result of previously successful class action lawsuits against health plans for systematically underpaying physician claims. In 2009 a class action settlement was reached between the American Medical Association and United Healthcare for the underpayment of non-contracted out-of-network provider services.18

The balance billing ban did serve the purpose of removing patients from billing disputes between emergency providers and health plans. RBOs, which are not directly regulated by the DMHC, appear to have taken advantage of the balance billing ban by substantially reducing payments to non-contracted emergency providers. Payments by the health plans did not appear to change significantly. However, the issue of fair payment between providers and health plans remains unresolved. A previous attempt to reduce billing disputes in California through fair payment legislation failed when such legislation was vetoed by then-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger.19 As a result, the lack of a clear fair payment standard will likely perpetuate billing disputes between providers and health plans.

Reduced emergency provider payments by health plans and RBOs may ultimately impact access to emergency care. By reducing payments to emergency providers in California, physician groups may have more difficulties staffing EDs. Emergency providers may leave California to go to states without a balance billing ban. Specialist may increasingly abandon the emergency department on-call roster. There may be a disproportionate impact on rural hospitals that already face difficulties staffing EDs. Additional studies will be required to determine if the reimbursement trends seen in this study will continue and potentially negatively impact access to emergency care.

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations to the study given that the survey was conducted in a blinded fashion. Since the survey participants were not asked to identify themselves, the study is unable to determine if the payment patterns are representative of all emergency providers in the state of California. The survey was conducted through the reimbursement committee of California ACEP and non-members were not able to participate. California ACEP does represent approximately 80% of EPs in the state of California. The survey also did not ask how many providers were associated with the claims that were submitted. The data submitted were not reviewed by an independent body to ensure accuracy.

It is possible that the survey was subjected to a selection bias and concentrated in a small percentage of providers. Information technology barriers could have prevented some emergency providers from submitting data for the survey. This might be particularly true for small groups of EPs that conduct self-billing. The survey may not have included small-volume payers. Since a small-volume payer was not defined in the survey, participants used their own judgment of what was considered to be a low-volume payer. Survey participants may have also submitted claims data for small-volume payers that reduced payments and excluded claims data for small-volume payers that did not reduce payment. The degree of this bias cannot be determined from this study.

Claims data for some health plans and RBOs were not available. The most likely explanation is that some health plans and RBOs are widely contracted with emergency care providers and therefore the contracted claims data would have been excluded from the study. The other possibility is that the survey respondents did not provide emergency care to enrollees in a particular health plan or RBO.

One other limitation of the study is the inability to establish a direct cause and effect between the balance billing ban and the decrease in emergency provider reimbursement. Other, unidentified factors may have produced the decreased payment over the time period of the study.

Finally, the reduction in percentages of charges paid may not represent a true reduction in payment per unit of service. For example, payment may not have changed based on a specific common procedural terminology (CPT) code. This explanation is unlikely to be true for RBOs since the reduction in the percentages of charges paid was much greater than the reduction by health plans. A percentage of charges was chosen as the outcome measure to avoid any anti-trust concerns associated with revealing actual charges, and remains a valid way to differentiate the payment policies of plans and RBOs.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, percentage of charges reimbursed for emergency provider services by RBOs decreased substantially following the prohibition of balance billing in California whereas this measure of reimbursement by health plans remained relatively unchanged. At this time, the impact of a balance billing ban on quality of care cannot be determined. However, there is concern that less stringent enforcement of fair payment standards following balance billing ban will lead to a decline in the financial viability of the emergency care safety, and threaten adequate access to timely and appropriate emergency department care.20

Footnotes

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Bing Pao, MD. Palomar Medical Center, 2185 Citracado Parkway, Escondido, CA 92029. Email: bingpao@cep.com. 7 / 2014; 15:518 – 522

Submission history: Revision received August 27, 2013; Submitted December 31, 2013; Accepted January 27, 2014

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. Dr. Bing Pao is a past Board Member of California ACEP and Director of Provider Relations and partner for CEP America. This research was supported by public policy Chapter Grant from ACEP. Dr. Riner is a past President of California ACEP and a consultant to MedAmerica, Inc.