| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Lalena M. Yarris, MD, MCR | Oregon Health and Science University, Department of Emergency Medicine, Portland, OR |

| Nicole M. DeIorio, MD | Oregon Health and Science University, Department of Emergency Medicine, Portland, OR |

| Sarah S. Gaines, MD | Oregon Health and Science University, Department of Emergency Medicine, Portland, OR |

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

We sought to characterize the experiences and preferences of applicants to emergency medicine (EM) residency programs about being contacted by programs after their interview day but before the rank list submission deadline.

Methods:

This cross-sectional study surveyed all applicants to an academic EM residency during the 2006–2007 interview cycle. Participation was anonymous and voluntary. We used a Web-based survey software program to administer the survey in February 2007, after rank lists were submitted. Two additional invitations to participate were sent over the next month. The instrument contained multiple-choice and free-text items. This study was submitted to our Institutional Review Board and was exempt from formal review.

Results:

240/706 (34%) of applicants completed the survey. 89% (214/240) of respondents reported being contacted by a residency program after their interview but before rank lists were due. Of those contacted, 91% report being contacted by e-mail; 67% by mail; and 55% by phone. 51% of subjects reported that being contacted changed the order of their rank list in at least one case. A majority of contacted applicants felt “happy” (58%) or “excited” (56%) about being contacted, but significant numbers reported feeling “put on the spot” (21%) or “uncomfortable” (17%).A majority felt that it is appropriate for programs to contact applicants after interview day but before the rank lists are submitted, but 39% of contacted subjects responded that contact by phone is either “always inappropriate” or “usually inappropriate.” Regarding perceptions regarding the rules of the match, 80% (165/206) of respondents felt it was appropriate to tell programs where they would be ranked, and 41% (85/206) felt it was appropriate for programs to notify applicants of their place on the program’s rank list.

Conclusion:

Most EM residency applicants report being contacted by programs after the interview day but before rank lists are submitted. Although applicants feel this practice is appropriate in general, over a third of subjects feel that contact by phone is inappropriate. These findings suggest that residency programs can expect a majority of their applicants to be contacted after an interview at another program, and shed light on how applicants perceive this practice.

INTRODUCTION

The National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) is a private, not-for-profit corporation established in 1952 that aims to provide an impartial venue for matching applicants’ and programs’ preferences for each other. In 2007 the NRMP enrolled 127 emergency medicine (EM) residency programs in the match, which offered 1,288 EM positions and filled 1,282 of those positions. Of those, 1,027 were filled with United States graduates and 234 with independent applicants. A total of 1,489 applicants applied to an EM residency program. Of those, 1,105 were graduates of accredited U.S. medical schools and 384 were independent applicants.1

In its Statement on Professionalism, the NRMP outlines an expectation that all match participants conduct their affairs in an ethical and professionally responsible manner. While there are specific guidelines for certain explicit violations of match ethics listed in the Match Participation Agreement, other potential violations are less well-defined and subject to interpretation. One such prohibition concerns misleading communications. While the NRMP “permits program directors and applicants to express a high degree of interest in each other,” it “prohibits statements implying a commitment.” The distinction between what is an expression of interest and what implies a commitment is left up to interpretation by the program and applicant. Although statements such as “we plan to rank you very high on our list” and “we hope to have the opportunity to work with you in the coming year” are noted to be non-binding, the NRMP reports that these statements are frequently misinterpreted. Applicants are advised to not rely on them when creating rank order lists, and program directors are advised to avoid making misleading statements in their interactions with applicants.2

Previous publications suggest that violations of professional behavior in the match process may be common.3–11 However, the frequency of misleading communications is unknown. In our experience advising students applying to EM residency programs, we have heard that there is wide variation in program practices regarding contacting applicants after the interview day but before rank lists are submitted. While some students report only rare contact by any means, other students report frequent communication by e-mail or phone. Both the variation in program practices, and the nature of communication (which often is interpreted as at least an “expression of interest”), can be confusing and anxiety-provoking for the applicant.

To our knowledge, there are no published descriptions of EM residency programs’ practices regarding contacting applicants after the interview day, a communication practice with the potential to be interpreted as misleading and impact applicants’ decisions in creating rank order lists. We sought to describe the experiences of our applicants regarding being contacted after interview day by EM residency programs, and characterize their perceptions regarding these communications.

METHODS

Study Design

This cross-sectional study surveyed all applicants to our EM residency program in the 2006–2007 NRMP cycle.

Study Setting and Population

This study was conducted at a three-year EM residency program that offered nine post-graduate year (PGY)-1 positions in the 2006–2007 cycle. During the study period, our program’s policy was to not contact interviewees after the interview day. Invitations to participate in the study were offered by e-mail to all 706 individuals who had applied to our program. Of these applicants, 62.5% were male, and 37.5% were female. One hundred twelve applicants (16%) had interviewed at our program. To reassure applicants of anonymity and emphasize we were interested in their overall interview experience rather than their experience at our program, the survey did not ask respondents if they interviewed at our program. The geographic distribution of the 706 eligible subjects included 174 (24.6%) from the Midwest, 125 (17.7%) from the Northwest, 96 (13.6%) from the Southeast, 193 (27.3%) from the West and 118 (16.7%) foreign medical graduates.

Study Protocol

All applicants to our residency program were invited to participate in an anonymous and voluntary Web-based survey. A commercially available survey software program was used to administer the survey in February 2007, after rank lists were submitted but before match results were announced. Two additional invitations to participate were sent over the next month. This study was submitted to our Institutional Review Board and was exempt from formal review.

Measurements

The survey used a combination of multiple-choice and interval-scale type items to assess applicants’ perceptions about whether they were contacted by EM residency programs after the interview day, followed by items that characterized the nature of the contact they received and their feelings about being contacted. Applicants who responded that they were not contacted were asked analogous questions assessing how they felt about not being contacted. Both groups were asked a question pertaining to their understanding of the “rules of the match.” The survey also asked applicants to provide the following information: number of EM programs applied to and interviewed at; number of EM programs ranked; participation in the couples match; and ranking programs outside of EM. The survey was piloted on 10 current residents and reviewed before the study was initiated. Minor formatting and wording edits were made to avoid ambiguity and improve understandability. No significant problems were identified.

Data Analysis

The survey software reported descriptive statistics for data. The response rate was calculated as the number of applicants who responded to the question that referred to our primary research objective (“Were you contacted, in any way, by a member of a residency program after your interview but before rank lists were due?”) divided by the number of applicants who were invited to participate. Other items were not made mandatory so that applicants who were uncomfortable or unsure answering a certain question could opt out of that question but still participate in the survey. All responses collected are reported. Percentages of respondents selecting each answer were calculated and compared between the contacted and not contacted groups.

RESULTS

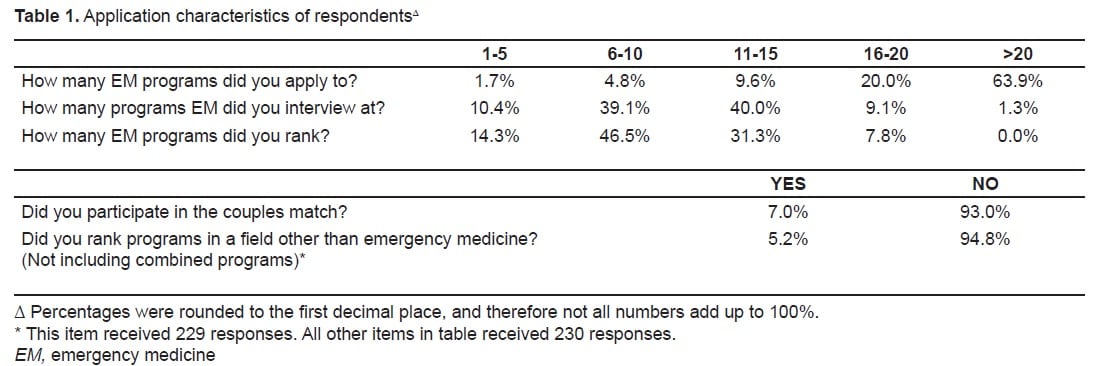

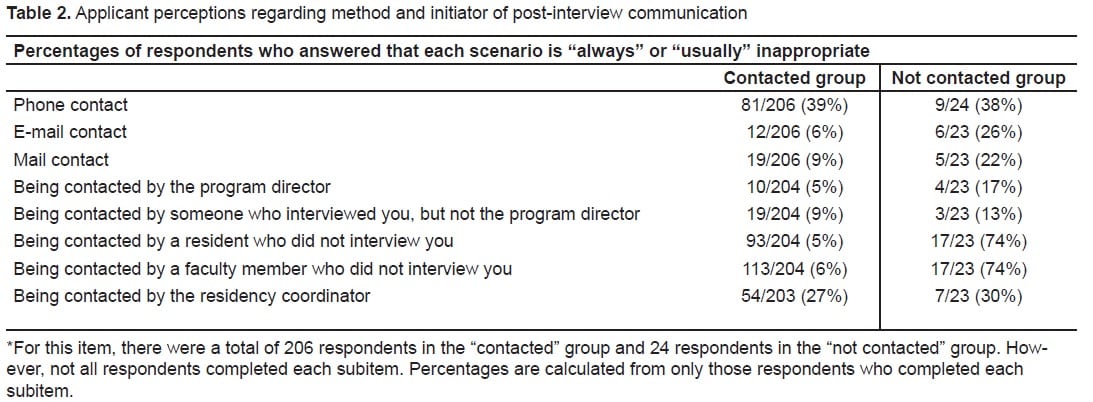

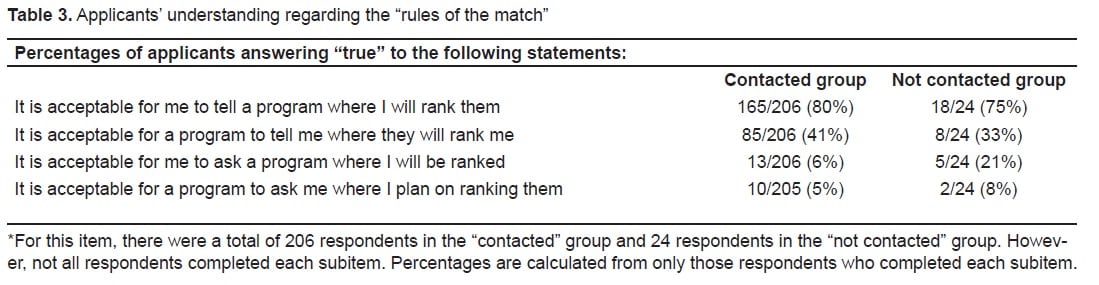

Of 706 applicants invited to participate, 240 (34%) completed the survey. Not all respondents completed each item, and therefore all percentages are reported for the total number of respondents for each item. Table 1 describes the type and number of programs respondents applied to, interviewed at, and ranked. Fifty-two percent (123/237) of respondents answered that they expectedto be contacted by a residency program after their interview but before rank lists were due; 89% (214/240) of respondents reported actually being contacted. Fifty-six percent were contacted by 3–5 programs, with a third of applicants being contacted by more than five programs and the remainder of respondents being contacted by fewer than three. Out of those who were contacted, 91% report being contacted by e-mail; 67% by mail; and 55% by phone (some applicants were contacted by more than one method, therefore numbers do not add up to 100%). Fifty-one percent reported that being contacted changed the order of their rank list in at least one case. A majority of contacted applicants felt “happy” or “excited” about being contacted, but significant numbers reported feeling “put on the spot” (21%), or “uncomfortable” (17%). Of the 25 respondents who were not contacted after the interview day, 48% reported feeling “nervous” and 48% reported feeling “disappointed” about their lack of contact. A majority of applicants in both groups (80% of contacted applicants, 73% of not contacted applicants) believed that it is appropriate for programs to contact applicants after interview day but before the rank lists are in, but 39% of contacted subjects responded that contact by phone is either “always inappropriate” or “usually inappropriate.”

Table 2 demonstrates responses regarding being contacted. Understanding of the “rules of the match” is depicted for both groups in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

During the annual residency match, program directors are faced with the challenge of adhering to the highest professional standards while competing with other programs for the most qualified applicants. Although the NRMP does provide a framework for this process, many decisions, ranging from how to select invitees, how to rank applicants, and how to communicate with top candidates after the interview day, are left up to the individual programs. Even if the nature of communication does not violate the rules of the match, program directors may risk offending applicants with contact that is either too direct, or by not providing communication that applicants expect because they are receiving it from other programs.

To avoid misleading communication, one pediatric residency program recently published their “no call policy” between interview day and the day rank lists are due, and reported that over a four-year period, 10.3% of respondents reported that a recruiting call would have caused them to rank those programs more favorably.12 Although communication after interview day is not meant to imply commitment, these data suggest that it does influence rank order lists for a subset of applicants.

To our knowledge, this is the first cross-sectional investigation of EM applicants’ perceptions about being contacted after the interview day but before the match. While over half of applicants reported that they expected to be contacted during this period, we were surprised to find that 89% actually were contacted. Although this represents a sample of the global pool of applicants, program directors can conclude that it is likely that a majority of their top candidates are being contacted by at least one other program after interview day. We have seen that the method and nature of this contact varies, but that in just over half of respondents, this communication did affect the placement of the program on their rank order list. This begs several follow-up questions: Are applicants flattered, and therefore ranking programs higher? Are they offended by the contact, and ranking them lower? Or do they perceive that they are not competitive because they were not contacted and thus rank the program lower in favor of other more persuasive programs?

While further studies are needed to answer these questions we did find that the contact that is presently being initiated by program directors is eliciting a variety of feelings in applicants, who report feeling everything from “happy” to “uncomfortable” due to this communication. Some programs directors may opt to have a “no contact” policy, but it is important to note that nearly half of the applicants who were not contacted felt “nervous” or “disappointed.” Programs may choose to address the issue directly with applicants by presenting the program policy and philosophy regarding this practice during or before the interview day.

For those programs that continue to contact applicants after the interview day, decisions must also be made about who should do the contacting, and how it should be done. While most respondents felt comfortable with e-mail contact, over a third deemed phone contact inappropriate – notable since 55% of contacted respondents reported receiving telephone communication. Similarly, few respondents rated being contacted by an interviewer or the program director as inappropriate, while a majority responded that being contacted by a resident or faculty who did not interview them is inappropriate.

In light of the NRMP’s prohibition of statements that imply a commitment, either on behalf of the program or applicant, we found applicants’ responses regarding the rules of the match intriguing. Over three-quarters of applicants felt it was appropriate to tell programs where they would be ranked, and over one-third felt it was appropriate for programs to notify applicants of their place on the program’s rank list. Although these practices may be common, they are not in compliance with the written rules of the match. Because they are not binding, these communications may also be misleading. If these results are applicable to a broader pool of EM applicants, and especially to applicants across specialties, they will be of interest to NRMP and medical school personnel charged with educating applicants about the rules of the match.

Our results suggest that a decision whether to contact top applicants after the interview day, and how to go about it, is indeed a decision that may cause reactions in applicants and even affect the order of their rank list. Further studies will be helpful in determining whether these results have external validity across a greater sample of applicants, and the most appropriate and ethical means by which to conduct communication with top residency candidates. This information is needed from a practical standpoint to best use the time and resources of academic departments and from a professional standpoint to ensure that our specialty adheres to highest ethical standards during a selection process that can at times lead us to push the boundaries of our professionalism.

LIMITATIONS

Our candidate pool may differ from the general pool of EM applicants in several ways. For example, an interviewee at our program may not be representative of candidates who consider other areas of the country or prefer a four-year program. Although our general applicant pool does represent a geographically and gender diverse population, in order to reassure applicants of their anonymity we did not collect this demographic information on respondents and therefore can not determine the ways that respondents differed from non-respondents. In addition, we opted to survey all applicants rather than only our interviewees to broaden our sample, as we only are only able to interview approximately the top 15% of our applicants. We recognized a priori that this may negatively impact our response rate, because applicants who were not offered an interview may be less interested in participating in a voluntary, anonymous study administered by our program months after they were not invited to interview. However, given the lack of any data on this topic in our field, we concluded that a more representative sample was more important than a traditionally high sample size, and our resulting relatively low sample size is a limitation of the study.

CONCLUSION

Most EM residency applicants report being contacted by programs after the interview day but before rank lists are submitted. Applicant perceptions regarding this communication vary widely depending on the method of communication and who they are being contacted by. Although applicants think this practice is appropriate in general, over a third of subjects believe that contact by phone is inappropriate. Furthermore, half of our respondents reported that being contacted by a residency program changed that program’s position on their rank list. These findings suggest that the decisions that residency programs make regarding their communication practices with applicants after the interview day are both important and may have a significant impact on the outcome of their match.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Michael Epter, DO

Submission history: Submitted October 2, 2009; Revision Received February 16, 2010; Accepted March 20, 2010

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Lalena M. Yarris, MD, MCR, Department of Emergency Medicine, Oregon Health and Science University, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Rd., Mail Code CDW-EM, Portland, OR 97239

Email yarrisl@ohsu.edu

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. [Accessed online February 16, 2010]. http://www.nrmp.org/data/resultsanddata2007.pdf.

2. [Accessed online February 16, 2010].http://www.nrmp.org/res_match/policies/professionalism.html.

3. Pearson RD, Innes AH. Ensuring compliance with NRMP policy. Acad Med. 1999;74(7):747–8.[PubMed]

4. Carek PJ, Anderson KD, Blue AV, Mavis BE. Recruitment behavior and program directors: how ethical are their perspectives about the match process? Fam Med. 2000;32(4):258–60. [PubMed]

5. Carek PJ, Anderson KD. Residency selection process and the match: does anyone believe anybody? JAMA. 2001;285(21):2784–5. [PubMed]

6. Iserson KV. Bioethics and graduate medical education: the great match. Camb Q Healthc Ethics.2003;12(1):61–5. [PubMed]

7. Anderson KD, Jacobs DM, Blue AV. Is match ethics an oxymoron? Am J Surg. 1999;177(3):237–9.[PubMed]

8. Anderson KD, Jacobs DM. General surgery program directors’ perceptions of the match. Curr Surg. 2000;57(5):460–5. [PubMed]

9. Lewis LD, Wagoner NE. Professionalism and the match. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:615–6. [PubMed]

10. Young TA. Teaching medical students to lie. The disturbing contradiction: medical ideals and the resident-selection process. CMAJ. 1997;156(2):219–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

11. Philips RL, Phillips KA, Chen FM, Melillo A. Exploring residency match violation in family practice. Fam Med. 2003;35(10):717–20. [PubMed]

12. Opel D, Shugerman R, McPhillips H. Professionalism and the match: a pediatric residency program’s post interview no-call policy and its impact on applicants. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e826–31. [PubMed]