| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Karen B. Hirschman, PhD, MSW | University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA |

| Helen H. Paik, BS | Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, PA |

| Jesse M. Pines, MD, MBA, MSCE | George Washington University, Washington, DC |

| Christine M. McCusker, RN, BSN | University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA |

| Mary D. Naylor, PhD, RN | University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA |

| Judd E. Hollander, MD | University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA |

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

Within the next 30 years, the number of visits older adults will make to emergency departments (EDs) is expected to double from 16 million, or 14% of all visits, to 34 million and comprise nearly a quarter of all visits. The objectives of this study were to determine prevalence rates of cognitive impairment among older adults in the ED and to identify associations, if any, between environmental factors unique to the ED and rates of cognitive impairment.

Methods:

A cross-sectional observational study of adults 65 and older admitted to the ED of a large, urban, tertiary academic health center was conducted between September 2007 and May 2008. Patients were screened for cognitive impairment in orientation, recall and executive function using the Six-Item Screen (SIS) and the CLOX1, clock drawing task. Cognitive impairment among this ED population was assessed and both patient demographics and ED characteristics (crowding, triage time, location of assessment, triage class) were compared through adjusted generalized linear models.

Results:

Forty-two percent (350/829) of elderly patients presented with deficits in orientation and recall as assessed by the SIS. An additional 36% of elderly patients with no impairment in orientation or recall had deficits in executive function as assessed by the CLOX1. In full model adjusted analyses patients were more likely to screen deficits in orientation and recall (SIS) if they were 85 years or older (Relative Risk [RR]=1.63, 95% Confidence Interval [95% CI]=1.3–2.07), black (RR=1.85, 95% CI=1.5–2.4) and male (RR=1.42, 95% CI=1.2–1.7). Only age was significantly associated with executive functioning deficits in the ED screened using the clock drawing task (CLOX1) (75–84 years: RR=1.35, 95% CI= 1.2–1.6; 85+ years: RR=1.69, 95% CI= 1.5–2.0).

Conclusion:

These findings have several implications for patients seen in the ED. The SIS coupled with a clock drawing task (CLOX1) provide a rapid and simple method for assessing and documenting cognition when lengthier assessment tools are not feasible and add to the literature on the use of these tools in the ED. Further research on provider use of these tools and potential implication for quality improvement is needed.

INTRODUCTION

Within the next 30 years, the number of visits older adults will make to emergency departments (EDs) is expected to double from 16 million, or 14% of all visits, to 34 million and comprise nearly a quarter of all visits.1,2 Compared to younger patients, older adults who visit the ED are at increased risk for functional decline and medical complications, poorer management of pain and health-related quality of life and repeat ED visits.3–7 With the aging of the population will come a surge in the number of older adults with cognitive impairment.8–10 Approximately 26% to 40% of older adults who visit the ED have some form of cognitive impairment.11–14 Among this group of patients found to be cognitively impaired in the ED, 80% have no prior history of dementia.11,15 The Society of Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) Geriatric Task Force named cognitive assessment as one of the three major gaps in quality of care for geriatric patients.16

Long wait times, treatment in noisy and congested hallways, and the lack of daylight all may influence the onset and level of cognitive impairment when elderly patients present in the ED.17Because these exposures are more common during peak times, it seems logical that ED crowding may affect the presence of cognitive impairment in older adults.

Screening for cognitive impairment using long, detailed assessment scales, such as the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), is not practical in the ED because of limited time and competing demands. Alternatives include shorter scales, such as the Six-Item Screen (SIS).18 The SIS is a brief scale that assesses orientation and recall. When compared to the MMSE, the SIS was found to be sensitive in detecting cognitive impairment in the ED (defined as MMSE<23); however, the sensitivity was lower than when the instrument was applied outside of the ED.2 This is most likely due to the fact that the SIS only assesses temporal orientation (day, month, year) and recall (three items). Adding the clock-drawing task (CLOX) to test executive function offers a more comprehensive approach to screening for cognitive impairment. The CLOX1 is simple, easy to administer and has been used with older adults.19–21 Knowledge of impairment in patients’ orientation, recall or executive function is clinically important in the ED because deficits in one or more areas may impair patients’ ability to provide an accurate medical history or medication list. Such deficits also negatively influence patients’ ability to understand and follow discharge instructions.2,22 To the best of our knowledge, no published studies have assessed using two tools (SIS and CLOX) to identify older adults with cognitive impairment in the ED.

The objectives of this study were to determine prevalence rates of cognitive impairment using the SIS and the CLOX1 and to identify associations, if any, between environmental factors unique to the ED and rates of cognitive impairment.

METHODS

Study Design

A cross-sectional, observational study of older adults admitted to the ED of a large, urban, tertiary academic health center was conducted to: identify rates of impairment among older adults; and identify relationships, if any, between ED environmental factors and presence of cognitive impairment.

Study Setting and Population

The ED at this academic health center contains 39 treatment beds with 25 private rooms and 14 hallway treatment areas. During the study period, the annual ED census was approximately 57,000 visits by adult patients, approximately 11.9% are >64 years of age.

Selection of Participants

Patients who presented to the ED between September 6, 2007, and May 1, 2008, were screened for cognitive impairment if they spoke English, were 65 years or older, lived within a 30-mile radius of the ED in the state of Pennsylvania, and lived independently (i.e., not in a nursing home). Patients were excluded from being screened for cognitive impairment if they had an end-stage disease with prognosis of six months or less, cancer diagnosis with active treatment, known alcohol or drug abuse, history of neurological disease (e.g., cerebral vascular accident with residual effects, multiple sclerosis, etc.), a previous medical history of dementia or delirium, or resided in a nursing home. These eligibility criteria and screening process presented here were established for a National Institutes of Health-funded large scale study (NIH/NIA R01-AG 023116).23 These analyses are part of this larger patient screening effort for eligibility. The exclusion criteria were selected because these conditions are likely to have cognitive impairment that would already be known prior to our assessment. All patients who met the inclusion criteria and were present in the ED between 7am and midnight, were approached by a trained research assistant in the ED who explained the screening and obtained verbal consent to be screened. This study was approved by Local Institutional Review Board.

Methods of Measurement

We assessed cognitive impairment using two validated screening tools: the SIS and CLOX1.2,18,19SIS is a brief and reliable scale designed to identify subjects with deficits in orientation and recall.18The patient is asked three temporal orientation questions (day of the week, month, year) and three recall items (hat, car, tree). Each correct answer is given a point towards a summed score (range: 0–6). The SIS has been used in the ED and with older adults as a screen to identify cognitive impairment among potential older adult research subjects.2,18 Patients with greater than two errors on the SIS were considered impaired. Patients who made fewer than two errors on the SIS were asked to complete a CLOX. The CLOX1 was chosen to assess for executive function impairments. Scores range from 0–15 in this subscale of the larger CLOX,19 with scores ≤10 indicating deficits in executive functioning. The CLOX1 tests executive control function and is strongly associated with cognitive test scores.20 The executive control functions are cognitive processes that coordinate simple ideas and actions into complex goal-directed behaviors. Examples include goal selection, motor planning sequencing, selective attention, and the self-monitoring of one’s current action plan. All are required for successful clock drawing. Together the SIS and CLOX1 take under five minutes to complete, and each is associated with severity of cognitive impairment.18,19 Patients were considered to have cognitive impairment deficits if they scored ≤4 on the SIS or ≤10 on the CLOX1.

Several ED specific environmental variables were documented by research assistants on a standardized data collection form. Patient triage time, “in-room” (or hallway) time, total patient-care hours (a sum of all the hours for all patients currently in the ED), number of admitted patients (number of patients who are admitted to the hospital but currently boarding in the ED), waiting room number (number of patients in waiting room) and triage level were queried from EMTRAC (Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA), a computerized patient tracking and charting system, and recorded in real time on each study form. We calculated total minutes waiting in triage by subtracting triage time from “in-room” time for each patient. Triage level is a nurse-assessed four-point scale (1–4) based on the urgency of the ED patient’s complaint, where “1” signified most emergent cases and “4” signified least urgent. Patient demographic information (race, gender, age), location of screening (hallway or private room), and if the patient was admitted or discharged to the hospital were also collected for each patient.

Outcome measures

There were two primary outcomes for this study. The first was to assess the prevalence of cognitive impairment among older adults visiting the ED, using the SIS and CLOX1. The second was to examine the relationship between cognitive impairment assessment (screened positive for cognitive impairment on either SIS or CLOX1 versus no impairment) and various patient and ED characteristics and to identify which environmental factors, if any, are associated with the assessment of cognitive impairment in the ED for older adults.

Primary Data Analysis

Data are reported as frequencies and percentages for categorical data, and as means ± standard deviation and range for continuous variables. Among patients with multiple ED visits during the study period, only data from one of the patients’ visits were used in our analyses.

We used a generalized linear model with a log link, Gaussian error, and robust estimates of the standard errors of the model coefficients to calculate relative risk (RR). We controlled for several patient-specific characteristics (age, sex, race [black], whether the patient was admitted to the hospital, time of day triaged at ED [7am-3pm, 3pm-11pm, 11pm-7am]), and ED characteristics (triage class [as an indicator variable compared to the most severe triage score], waiting time, crowding, location of interview [private room]) in a final model. We determined the list of confounders a priori. To control for the affect of all a priori confounders all were included in a final model; no stepwise techniques were used to select variables. Given the large number of outcomes, the study was adequately powered for multivariable analysis. We used the Bonferroni correction of n=14 to adjust for covariates because of the multiple statistical tests performed on the data. Based on this, a probability of <0.003 was considered statistically significant.

Data for these analyses are presented as relative risks with 95% confidence intervals. We performed all analyses using Stata statistical software (Version 10, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Subjects

Between September 6, 2007, and May 1, 2008, 1,095 patients were admitted to the study and were approached by the research assistants, of whom 266 were subsequently excluded (Figure 1). Of the remaining 829, patients were predominantly black (67.5%) and female (65.1%). Patients ranged from 65 to 105 years old (mean age: 75.7± 7.1 standard deviation). See Table 1.

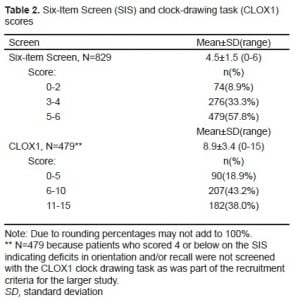

The prevalence of cognitive impairment assessed using the SIS and CLOX1 is summarized in Table 2. A total of 42% percent (350/829) presented with deficits in orientation and recall. An additional 36% (297/829; 62% of patients [297/479] visiting the ED who passed the SIS) had deficits in executive function. None of these patients had a documented history of dementia or other cognitive impairment noted at the ED visit.

Table 3 shows the results from the multivariate analysis. The adjusted analyses for screening positive using the SIS and the subsample that were screened using the CLOX1 showed that only patient demographics were significantly associated with screening positive for cognitive impairment in the ED. Specifically patients were more likely to screen positive for cognitive impairment using the SIS if they were 85 years or older (RR 1.63, p<0.001), black (RR 1.85, p<0.001) and male (RR 1.42, p<0.001). Interestingly, only age was significantly associated with screening positive for cognitive impairment in the ED using the CLOX1 (75–84 years: RR 1.35, p<0.001; 85+ years: RR 1.69, p<0.001). Race and gender were no longer significant in the full model when using the CLOX1 to assess for deficits in executive functioning with this clock-drawing task. Time of day triaged, number of people in the waiting room, number of admitted patients, total patient hours, being screened in a private room, and the admission status of the patient were not associated with screening positive for cognitive impairment in the ED in either of the full models.

DISCUSSION

This study explored whether the SIS and CLOX1, executive clock-drawing task, can be used in the ED to easily assess and identify possible cognitive impairment among older adults. A high proportion of patients presented to the ED with deficits in orientation and recall (42%) and among those elders who passed the SIS, 36% had executive-functioning deficits. Only demographics (age, race, and gender) were significantly associated with screening positive for cognitive impairment in the ED. None of the environmental factors assessed were significant in the adjusted model. These results have four major implications.

First, a substantial number patients age 65 and older admitted to the ED present with impairments in orientation, recall and/or executive functioning. Our findings with respect to deficits in orientation and recall are consistent with those other studies that have reported between 26% and 40% of all ED elders have some form of cognitive impairment.2,15 These studies included people with dementia as well as delirium. This tool is short and easy to administer, allowing for a quick and reliable way of assessing deficits in orientation and recall, which may affect a patient’s ability to provide reliable self-report of symptoms and medications, as well as influence a patient’s ability to remember instructions post discharge from the ED. With respect to the assessment of executive function, there has been only one study to our knowledge that has used CLOX1 as part of a cognitive assessment in the ED.14 The tool used in that study did not score this task in as much detail to determine the level of impairment in executive functioning and was part of a tool that had a three-item recall (Mini-Cog).24 The clock-drawing task identified an additional 36% of older patients seen who have deficits in executive function with few or no deficits in orientation and recall (SIS >4). These results highlight the fact that although a similar proportion of older adults being seen in the ED have deficits in orientation and recall, a subset of older adults being seen in the ED have significant deficits in executive function. Together these two tools can be used to assess and document cognitive impairment in older adults in the ED, as was recommended by the SAEM Geriatric Task Force as a quality indicator.16 Using both tools can provide a more comprehensive snapshot of the patient’s cognitive status at admission to the ED.

Second, being male in our sample was significantly associated with positive screens for cognitive impairment using the SIS. This is an interesting finding since women are more likely than men to have Alzheimer’s disease or other types of dementia.8 However, this is due to women living longer.25 Yet in our data, after controlling for age and race, being male was still a significant predictor to screening positive for cognitive impairment in the ED using the SIS. The age group 75–84 years was not a significant predictor of screening positive on the SIS based on our Bonferroni correction (p≤0.003). However, it is worth noting that the p-value was 0.006 and rejecting this as a significant predictor may be a Type II error. Future research assessing gender differences using the SIS as a screening tool for research subjects in the ED is needed.

Third, being black in this sample was also a predictor of screening positive for cognitive impairment using the SIS. Other researchers have found that racial differences do not persist when age, gender, education and comorbid conditions are included in the analyses.25–28 It is possible that comorbid conditions and educational level may confound this association, but we did not collect that data.

Finally, this is the first study known by the authors to have controlled for no ED-specific environmental variables (e.g., crowding, time of triage, triage class, location of screening, wait time, etc.) in relation to screening cognitive impairment. The finding that only patient demographics were significant predictors of cognitive impairment while no ED-specific environmental variables supports the use of assessment tools such as the SIS and CLOX1 in the ED. Future research over the length of an ED stay to confirm that these environmental factors are not associated with the assessment of cognitive impairment is needed.

LIMITATIONS

There are a number of limitations to this study. First, we did not assess changes in impairment over time, which may occur with prolonged ED stays or though progression of disease. We found no association between ED crowding and cognitive impairment, which may be because patients were approached early in their ED visit and may not have had sufficient exposure to be injured by the crowded environment.

Second, screening of patients was limited to 7AM to midnight; therefore, elderly patients triaged between midnight and 7AM were missed. However this is <10% of this population that present to the ED during midnight to 7AM. Third, delirium was not formally assessed using a separate tool such as the Confusion Assessment Method.29 It is possible that some elders who screened positive on either scale were in fact experiencing delirium at the time of the screening. Other researchers have reported that approximately 7–10% of patients screen positive for delirium in the ED.11,15However, the research previously published using the SIS in the ED did not differentiate delirium and other types of cognitive impairment stating, “A hallmark of the diagnosis of delirium is recognizing that impairment of memory and orientation exists.”14,22 Overall, the use of assessment tools, such as the SIS and CLOX1, support the SAEM Geriatric Taskforce recommendation that rapid and objective assessment and documentation of cognition in older adults in the ED as a quality indicator.

Finally, we were limited in that the assessment was only conducted in the ED. Impairment may develop or recede later if patients are screened after admission to the hospital. Future studies should include a follow-up assessment of cognitive impairment to determine changes over time and specific assessment for other types of impairments, such as delirium. Finally, the generalizability of the results may be limited due to this study being conducted at only one academic urban ED and the high proportion of black study members.

CONCLUSION

These findings suggest that a high proportion of elders are either admitted to the hospital from the ED or are being discharged from the hospital with cognitive deficits, specifically loss of executive function. The SIS assessment of orientation and recall coupled with a clock-drawing task can be used in the ED to easily assess cognition. These two tools (SIS and CLOX1) provide a rapid and simple method for assessing and documenting cognition when lengthier assessment tools are not feasible and add to the literature on the use of these tools in the ED. Further research assessing the impact of using these brief cognitive screens on the course of treatment (i.e., in ED, during hospitalization, and post discharge follow up assessments) and potential implication for quality improvement is needed.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Teresita M Hogan, MD

Submission history: Submitted December 3, 2009; Revision received May 31, 2010; Accepted April 18, 2010

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Karen B. Hirschman, PhD, MSW, University of Pennsylvania, School of Nursing, 3615 Chestnut Street Rm 334, Philadelphia, PA 19104

Email: hirschk@nursing.upenn.edu

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

This work was co-funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIH/NIA R01-AG023116; PI: Mary D. Naylor) and the Marian S. Ware Alzheimer Program at the University of Pennsylvania.

REFERENCES

1. Nawar EW, Niska RW, Xu J. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2005 emergency department summary. Advance Data. 2007 Jun 29;386:1–32. [PubMed]

2. Wilber ST, Carpenter CR, Hustey FM. The Six-Item Screener to detect cognitive impairment in older emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2008 Jul;15(7):613–6. [PubMed]

3. Bernstein E. Repeat visits by elder emergency department patients: sentinel events. Acad Emerg Med. 1997 Jun;4(6):538–9. [PubMed]

4. Chin MH, Jin L, Karrison TG, et al. Older patients’ health-related quality of life around an episode of emergency illness. Annals Emerg Med. 1999 Nov;34(5):595–603.

5. Denman SJ, Ettinger WH, Zarkin BA, et al. Short-term outcomes of elderly patients discharged from an emergency department. J of the Am Geriatrics Society. 1989 Oct;37(10):937–43.

6. Jones JS, Johnson K, McNinch M. Age as a risk factor for inadequate emergency department analgesia. Am J of Emergy Med. 1996 Mar;14(2):157–60.

7. McCusker J, Ionescu-Ittu R, Ciampi A, et al. Hospital characteristics and emergency department care of older patients are associated with return visits. Acad Emerg Med. 2007 May;14(5):426–33.[PubMed]

8. Alzheimer’s A. 2009 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia : J of the Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2009 May;5(3):234–70.

9. Caltagirone C, Perri R, Carlesimo GA, et al. Early detection and diagnosis of dementia. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2001;7(suppl):67–75. [PubMed]

10. Schumacher JG. Emergency medicine and older adults: continuing challenges and opportunities.Am J Emerg Med. 2005 Jul;23(4):556–60. [PubMed]

11. Hustey FM, Meldon SW. The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Annals Emerg Med. 2002 Mar;39(3):248–53.

12. Kakuma R, du Fort GG, Arsenault L, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients discharged home: effect on survival. J of the Am Geriatrics Society. 2003 Apr;51(4):443–50.

13. Naughton BJ, Moran MB, Kadah H, et al. Delirium and other cognitive impairment in older adults in an emergency department. Annals Emerg Med. 1995 Jun;25(6):751–5.

14. Wilber ST, Lofgren SD, Mager TG, et al. An evaluation of two screening tools for cognitive impairment in older emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2005 Jul;12(7):612–6.[PubMed]

15. Hustey FM, Meldon SW, Smith MD, et al. The effect of mental status screening on the care of elderly emergency department patients. Annals Emerg Med. 2003 May;41(5):678–84.

16. Terrell KM, Hustey FM, Hwang U, et al. Quality Indicators for Geriatric Emergency Care. Acad Emerg Med. 2009 Mar 28;

17. Hwang U, Morrison RS. The geriatric emergency department. J of the Am Geriatrics Society.2007 Nov;55(11):1873–6.

18. Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, et al. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Medical Care. 2002 Sep;40(9):771–81. [PubMed]

19. Royall DR, Cordes JA, Polk M. CLOX: an executive clock drawing task. J Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1998 May;64(5):588–94.

20. Royall DR, Mulroy AR, Chiodo LK, et al. Clock drawing is sensitive to executive control: a comparison of six methods. J of Gerontology. Series B. 1999 Sep;54(5):P328–33.

21. Shah MN, Karuza J, Rueckmann E, et al. Reliability and validity of prehospital case finding for depression and cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009 Apr;57(4):697–702. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

22. Wilber ST, Gerson LW, Terrell KM, et al. Geriatric emergency medicine and the 2006 Institute of Medicine reports from the Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the U.S. health system.Acad Emerg Med. 2006 Dec;13(12):1345–1351. [PubMed]

23. Naylor MD, Hirschman KB, Bowles KH, et al. Care Coordination for Cognitively Impaired Older Adults and Their Caregivers. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2007;26(4):57–78. [PMC free article][PubMed]

24. Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M, et al. The mini-cog: a cognitive ‘vital signs’ measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000 Nov;15(11):1021–7. [PubMed]

25. Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of dementia in the United States: the aging, demographics, and memory study. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29(1–2):125–32. [PMC free article][PubMed]

26. Fillenbaum GG, Heyman A, Huber MS, et al. The prevalence and 3-year incidence of dementia in older Black and White community residents. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998 Jul;51(7):587–595. [PubMed]

27. Gurland BJ, Wilder DE, Lantigua R, et al. Rates of dementia in three ethnoracial groups.International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1999 Jun;14(6):481–93. [PubMed]

28. Kukull WA, Higdon R, Bowen JD, et al. Dementia and Alzheimer disease incidence: a prospective cohort study. Archives of Neurology. 2002 Nov;59(11):1737–46. [PubMed]

29. Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990 Dec 15;113(12):941–8. [PubMed]