| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Joshua R. Parker, MD | University of Nevada School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Las Vegas, NV |

| Ross P. Berkeley, MD | University of Nevada School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Las Vegas, NV |

ABSTRACT

Toxic epidermal necrolysis is a rare disease that is most often drug-induced but can be of idiopathic origin. We present a case that originated at the site of a cigarette burn to the forearm and review the key elements of physical exam findings and management of this life-threatening dermatological condition, which needs to be promptly recognized to decrease patient mortality.

INTRODUCTION

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a rare entity, with a reported incidence of 0.4 to 1.9 cases per million person-years.1,2 It is one of the few dermatological emergencies that must be promptly diagnosed in the emergency department (ED). The disorder is typically drug-induced, with the most commonly cited agents including sulfonamide antibiotics, oxicam non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), anticonvulsants, and allopurinol.3 Various other precipitants have been reported, including food additives, fumigants and chemical contacts, aerosolized pentamadine and graft-versus-host disease.1,2,4 We describe a case of TEN that originated at the site of a cigarette burn to the forearm.

CASE REPORT

A 31-year-old black male with no significant past medical history presented to the ED at his family’s insistence, complaining of open sores covering his body. The patient recalled the sores began at the site of a cigarette burn to his left forearm two weeks prior to presentation, and subsequently spread diffusely over the body. The lesions were slightly tender to the touch. Review of systems was negative for a viral prodrome, and the patient denied any fevers, chills, or sweats. He denied any chest pain or shortness of breath, and there had been no abdominal pain, nausea or vomiting. There was no history of ill contacts, animal exposure, insect bites or recent travel. The patient denied intravenous drug use, but admitted to chronic use of tobacco, alcohol and marijuana. The patient reported he had not been taking any medications, denied any known allergies, and denied any significant family history. He had sought no medical care for his symptoms until this ED presentation.

Upon arrival to the ED via ambulance, the patient was obviously anxious and avoided unnecessary movement. Temperature was 100.1°F, heart rate was 145 beats per minute, blood pressure 124/77 mm Hg, respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute, with oxygen saturation 99% on room air. Heart tones were regularly tachycardic, free of murmurs or rubs. Pulmonary exam was clear to auscultation bilaterally, without crackles or wheezes. There was no edema of the extremities, no lymphadenopathy, and no hepatosplenomegaly.

Skin exam (Figure 1) revealed diffuse regions of skin sloughing with necrosis and a mildly erythematous base along the dermis; there were occasional small bullae and vesicles. Over 50% of the patient’s total body surface area (BSA) was involved, including his back, abdomen, scrotum, and perirectal area. However, the forehead and scalp were spared. There was no purulent discharge, pustules, purpura or ulcerations, but a strong foul-smelling odor was noted. The non-affected area of the patient’s skin easily sloughed with lateral traction. The oral mucosa was injected and sloughing apparent. Conjunctivae were spared.

After the patient’s temperature increased to 101.7° F on repeat assessment, vancomycin and meropenem were administered, and blood cultures were sent. The patient received four liters intravenous (IV) normal saline while in the ED, and was made comfortable with morphine. Pertinent laboratory values included a white blood cell count of 12,000/mm and a lactic acid of 2.8 mmol/L, serum bicarbonate 21 mmol/L, serum glucose 140 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen 9 mg/dL, creatinine 0.9 mg/dL and anion gap 10 mmol/L. The patient remained stable, although persistently tachycardic, and was admitted to the intensive care unit.

He subsequently developed severe sepsis, and blood cultures returned positive for oxacillin-sensitive Staphylococcal aureus. Per recommendation of the dermatology consultant, the patient was empirically started on steroids and received intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). He was cared for in the Burn Care Unit and underwent multiple surgical debridement procedures. Skin biopsy revealed “non-specific epidermal necrosis, consistent with TEN,” according to the pathologist, although further specifics of the histopathology were not described. The patient was ultimately discharged home after a protracted hospital stay.

DISCUSSION

While the pathophysiology of TEN is unclear, immunologic and metabolic etiologies have been theorized.5 TEN is currently considered an extreme form of a continuum of disease, which includes Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and erythema multiforme, although there is debate regarding inclusion of the latter.6,7 There is a significant associated mortality rate, ranging between 30–50%, largely due to secondary infection and multi-organ dysfunction syndrome.3,6

The cutaneous involvement of TEN is classically characterized by regions of confluent erythema with extensive blistering and desquamation, encompassing >30% of total body surface area (BSA); the scalp is characteristically spared.1,2,8 The disease is often preceded by a viral syndrome, followed by a central-to-peripheral spreading macular exanthem.2,3 Mucous membrane involvement is generally present and can potentially lead to respiratory distress.1–3 Due to epidermolysis, a positive Nikolsky’s sign (shearing of epidermis from dermis with light manual traction) is universally present.1,2,6,9

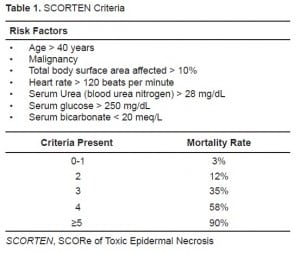

Once the diagnosis is suspected, key elements of management include cessation of the offending agent, supportive care, and transfer to a regional burn care center.3,6 Airway-protective considerations must be taken into account, as tracheal and bronchial sloughing may cause obstruction.3 While fluid management is vital in TEN, it differs from thermal injury management since there tends to be a smaller overall fluid loss due to a lesser systemic inflammatory response and a smaller degree of capillary permeability.6,10 No current gold-standard formula exists to calculate fluid resuscitation, but titrating IV crystalloid to achieve a urine output ≥0.5 mL/kg/hr is reasonable. Exposed dermis should be covered to decrease the risk of infection; however, prophylactic antibiotics are not routinely recommended and can potentially complicate the clinical course by selecting resistant organisms.2,3,6 Early transfer of patients with TEN to a burn care center, after initial stabilization, has shown to reduce mortality.11 A validated severity-of-illness scoring system (SCORTEN), consisting of seven variables, has been developed to predict the mortality risk (Table 1).12

A definitive abortive treatment of TEN has yet to be established. Several different treatment modalities have been used with varying degrees of success, including corticosteroids, thalidomide, plasmapheresis, and IVIG; few of these are practical for use in the ED.13–18

CONCLUSION

In this patient, the temporal and physical relationship of the cigarette burn to the onset of symptoms was suggestive that this may have been the inciting event. However, upon further questioning during his hospitalization, he admitted to over-the-counter NSAID use sometime prior to the onset of his symptoms, making the true etiology of this case difficult to pinpoint; it is conceivable that the forearm may have simply been the first location to manifest dermatologic symptoms due to the pre-existing traumatic insult. The patient’s septicemia was likely secondary to, and not the cause of, his disease since he was otherwise healthy during the two weeks prior to seeking medical care, and the malodor noted is consistent with secondary bacterial infection of the necrotic tissue. Although there are other disorders with similar dermatologic appearance that could be considered, such as Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, this entity most commonly affects young children, and the biopsy report in this case was consistent with TEN.

Reported offending agents in TEN are diverse and most often pharmacologic. Although an uncommon disease, TEN carries a high rate of mortality, which has been shown to be decreased by early transfer to a burn care center. Early recognition of the disease and supportive care are the mainstays of emergency care. Available treatment modalities, both in the ED and in hospital, are limited and have variable efficacy, and antibiotics should be reserved for confirmed infections.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Brandon K. Wills, DO, MS

Submission history: Submitted January 29, 2010; Accepted February 22, 2010

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Joshua R Parker, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Nevada School of Medicine, 901 Rancho Lane, Suite #135, Las Vegas, NV 89106

Email: joshuaRparker@gmail.com

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Becker DS. Toxic epidermal necrolysis. Lancet. 1998;9:1417–20. [PubMed]

2. Letko E, Papaliodis DN, Papaliodis GN, et al. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;94:419–36. [PubMed]

3. Browne BJ, Edwards B, Rogers RL. Dermatologic emergencies. Prim Care. 2006;33:685–95.[PubMed]

4. Watarai A, Niiyama S, Amoh Y, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis caused by aerosolized pentamidine. The American Journal of Medicine. 2009;122

5. Abe R. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens—Johnson syndrome: Soluble fas ligand involvement in the pathomechanisms of these diseases. Journal of Dermatological Science.2008;52:151–9. [PubMed]

6. Endorf FW, Cancio LC, Gibran NS. Toxic epidermal necrolysis clinical guidelines. J Burn Care Res.2008;29:706–12. [PubMed]

7. Auquier-Dunant A, Mockenhaupt M, Naldi L, et al. SCAR study group severe cutaneous adverse reactions. Correlations between clinical patterns and causes of erythema multiforme majus, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis: results of an international prospective studyArch Dermatol 2002. 1381019–24.24. [PubMed]

8. Sehgal VN, Srivastava G. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) Lyell’s syndrome. J Dermatolog Treat.2005;16:278–86. [PubMed]

9. Abood GJ, Nickoloff BJ, Gamelli RL. Treatment strategies in toxic epidermal necrolysis syndrome: where are we at? J Burn Care Res. 2008;29:269–76. [PubMed]

10. Borchers A, Lee J, Naguwa S, et al. Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis.Autoimmunity Reviews 7. 2008:598–605.

11. McGee T, Munster A. Toxic epidermal necrolysis syndrome: mortality rate reduced with early referral to regional burn center. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:1018–22. [PubMed]

12. Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M, et al. SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:149–53. [PubMed]

13. Majumdar S, Mockenhaupt M, Roujeau J, et al. Interventions for toxic epidermal necrolysis.Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(4)

14. Ducic I, et al. Outcome of patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis syndrome revisited. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:768–73. [PubMed]

15. Klausner JD, Kaplan G, Haslett PA. Thalidomide in toxic epidermal necrolysis. Lancet.1999;353:324. [PubMed]

16. Barnichas G, et al. Plasma exchange in patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis. Ther Apher.2002;6:225–8. [PubMed]

17. Jolles S, Sewell WA, Misbah SA. Clinical uses of intravenous immunoglobulin. Clin Exp Immunol.2005;142:1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

18. Brown KM, Silver GM, Halerz M, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: does immunoglobulin make a difference? J Burn Care Rehabil. 2004;25:81–8. [PubMed]