| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Monica H. Swahn, PhD, MPH | Georgia State University, Institute of Public Health, Atlanta, GA |

| Volkan Topalli, PhD | Georgia State University, Department of Criminal Justice, Atlanta, GA |

| Bina Ali, MPH | Georgia State University, Institute of Public Health, Atlanta, GA |

| Sheryl M. Strasser, PhD, MPH, MSW, MCHES | Georgia State University, Institute of Public Health, Atlanta, GA |

| Jeffrey S. Ashby, PhD | Georgia State University, Counseling and Psychological Services, Atlanta, GA |

| Joel Meyers, PhD | Georgia State University, Counseling and Psychological Services, Atlanta, GA |

| Author | Affiliation |

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

We examined the association between pre-teen alcohol use initiation and the victimization and perpetration of bullying among middle and high school students in Georgia.

Methods:

We computed analyses using data from the 2006 Georgia Student Health Survey (N=175,311) of students in grades 6, 8, 10 and 12. The current analyses were limited to students in grades 8, 10 and 12 (n=122,434). We used multilogistic regression analyses to determine the associations between early alcohol use and reports of both victimization and perpetration of bullying, perpetration only, victimization only, and neither victimization or perpetration, while controlling for demographic characteristics, other substance use, peer drinking and weapon carrying.

Results:

Pre-teen alcohol use initiation was significantly associated with both bullying perpetration and victimization relative to non drinkers in bivariate analyses (OR=3.20 95%CI:3.03–3.39). The association was also significant between pre-teen alcohol use initiation and perpetration and victimization of bullying in analyses adjusted for confounders (Adj.OR=1.74; 95%CI:1.61–1.89). Overall, findings were similar for boys and girls.

Conclusion:

Pre-teen alcohol use initiation is an important risk factor for both the perpetration and victimization of bullying among boys and girls in Georgia. Increased efforts to delay and reduce early alcohol use through clinical interventions, education and policies may also positively impact other health risk behaviors, including bullying.

INTRODUCTION

Bullying in schools is a significant public health problem that has received renewed interest and attention because of its widespread scope and devastating consequences.1–6 The state of Georgia is no exception and, in 2010, the Georgia General Assembly modified the existing law by expanding the definition of bullying and requiring local school districts to notify parents when their child bullies or is a victim of bullying.7 Moreover, the law was also modified to require school districts to adopt policies that prohibit bullying and to have age-appropriate consequences and interventions available for all schools.7 With these policy changes there will likely be opportunities to address risk factors for bullying. Bullying perpetration and bullying victimization have been associated with psychosocial problems, including frequent excessive drinking among middle and high-school students.1,2 However, less is known about the role of early alcohol use initiation in bullying, despite a growing literature indicating a strong link between early alcohol use initiation and a range of other health-risk behaviors and outcomes.8–18

Early alcohol use is highly prevalent in the United States (U.S.) where nearly 8,000 adolescents ages 12–17 use alcohol for the first time on an average day.19 Moreover, national data show that 21% of high school students initiate alcohol use prior to age 13.20 Early alcohol use is an important risk factor for adverse short- and long-lasting health problems, such as alcohol dependence, other substance use and criminal activity, unintentional injuries, unplanned and unprotected sex, suicidal ideation and attempts, and involvement in youth and dating violence.8–17 However the association between age of alcohol use initiation and bullying perpetration and victimization appears not to have been previously examined in a large, representative population and may have important implications for future policy, research and practice.

METHODS

The Georgia Student Health Survey, conducted in 2006, was administered to 181,316 students in the sixth, eighth, tenth, and 12th grades. Data were collected in middle and high schools to assess youth risk behaviors and other factors.16,21 Of the 181,316 completed questionnaires, 6,005 were eliminated due to an affirmative response on a validity check question regarding a fictitious drug (Have you ever used the drug zenabrillatol?), resulting in 175,311 remaining valid completed questionnaires. The overall participation rate was 45.9%. The distribution of study participants by sex (girls 51.4%, boys 49.6%) and race/ethnicity (White 47%, Black 38%, Latino 7%, other 4%, Asian 3%) closely match the population demographics for the school year (White 49%, Black 38%, Latino 8%, Asian 3%). The survey was designed by the state’s Department of Education to gather information required by the Federal Department of Education for annual yearly progress reporting. Students in grades six, eight, ten and 12 who attended public middle and high schools participated in the study by completing the surveys anonymously and on school computers during school hours. Investigators obtained parental permission for participation via a passive consent process. Investigators received approval from the local institutional review board to conduct secondary analyses of this database.

Measures

Early alcohol use initiation was assessed by asking students the age when they started using alcohol. We trichotomized responses to indicate alcohol use initiation prior to, or after, reaching the age of 13 or if the participant was a nondrinker. Students were also asked if they had five or more drinks in one sitting (binge drink), and responses were coded to indicate binge drinking on one or more days in the past month. Students were also asked a question about where their peers drink alcohol with a response option indicating that their peers were nondrinkers (responses were coded to indicate any versus no peer drinking). Participants were also asked if they currently use alcohol and other drugs (responses coded to indicate any versus no current alcohol or drug use) and if they brought a weapon to school in the past month (responses coded to indicate having brought any weapon to school versus not). Students were asked separate questions to determine if they had been bullied or threatened or if they had bullied or threatened others in the past 30 days. We combined responses to these dichotomous questions to create a four-level variable to indicate bully victimization only, bully perpetration only, both bully perpetration and victimization, and neither. Students also reported demographic characteristics including sex, race/ethnicity, and grade level.

Analyses

We conducted cross-sectional multilogistic regression analyses to determine the associations between alcohol use initiation and bullying involvement. Unadjusted and adjusted models were computed. All analyses were limited to students in grades 8, 10 and 12 (n=122,434). We analyzed data using the SAS 9.2 and SUDAAN 10.0 statistical software.

RESULTS

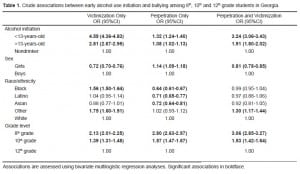

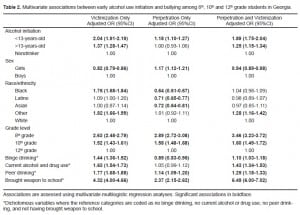

Among student participants, 24.4% reported bully involvement as a perpetrator (8.9%), a victim, (8.7%) or both (6.8%). Involvement in bullying, which varied by sex, race/ethnicity and grade level, is shown in unadjusted and adjusted models (Table 1 and Table 2). Pre-teen and teen alcohol use initiation was associated with all forms of bullying involvement (victimization, perpetration and both) in unadjusted analyses, although pre-teen alcohol use initiation had the strongest odds ratios for victimization and both bully perpetration and victimization. In adjusted models, pre-teen alcohol use initiation was associated with all forms of bullying even when considering the role of binge drinking, current alcohol and drug use, peer drinking and bringing a weapon to school.

DISCUSSION

This study found significant associations between pre-teen alcohol use initiation and bullying involvement among youth in Georgia. Youth who reported pre-teen alcohol use initiation were significantly more likely than non-drinkers to report any form of bullying and these associations remained statistically significant even when controlling for potential confounding variables. These findings support earlier research indicating that early alcohol use initiation is associated with a range of risk behaviors and that bullying is strongly linked to alcohol use.1,2, 8–18 It is particularly intriguing to note that pre-teen alcohol use initiation remained more strongly associated with all forms of bullying than current binge drinking. Binge drinking has been associated with violence among youth across studies.22–26 Therefore, the current findings demonstrate the importance of researching the circumstances in which adolescents initiate alcohol use and why they continue to drink.27–31 Moreover, the findings show that pre-teen alcohol use initiation had the strongest association with victimization only, which also raise new questions about the factors associated with victimization, perpetration or both. More research is needed to better determine the concurrent risk behaviors associated with different profiles of bullying behaviors.

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations that should be considered when interpreting these findings. First, the study is based on self-reported data of students in Georgia and results may not generalize to other populations or to youth who no longer attend school. It should be noted, however, that the prevalence of early alcohol use initiation prior to age 13 among high school students in Georgia is not different from the rest of the nation (20.7% in Georgia compared to 21.1% nationwide).32 Moreover, the prevalence of bullying in Georgia in the past month was somewhat lower than the national rates reported from 1998 (over a school term and among students in sixth through tenth grades) but may be explained by the different time periods captured (past month versus school term) as well as age groups included.1 Second, while the study was based on a census of students in Georgia, not a sample, the relatively low participation rate (45.9%) may limit the generalizability of the findings to beyond students who participated in the survey. Nonetheless, the analyses are based on a very large number of participants (n=122,434) which increases the likelihood that the findings are indeed representative of a large population of students. Third, while the findings show statistically significant associations, more specific temporal ordering cannot be determined, nor can causality be inferred. Fourth, other factors not assessed in the survey or analyses, such as sadness, child maltreatment experiences, and other family factors such as exposures to alcohol use, may also be important in the associations between early alcohol use and bullying.29,33

CONCLUSION

The current study examined the association between early alcohol use initiation and bullying in a very large epidemiological survey of students in Georgia. The findings show that early alcohol use initiation is an important risk factor for bullying involvement. Future longitudinal research is needed to better determine the circumstances in which adolescents initiate alcohol use and how these motives and contexts may be related to bullying involvement. In the context of the recently implemented new policies regarding bullying, particularly in Georgia, it will be important to assess the extent to which these policies will have a positive impact on bullying, as well as the significant risk factors for bullying such as early alcohol use. Perhaps more importantly for policy and practice, given the strong associations observed between alcohol use initiation and bullying, combined efforts that seek to reduce and prevent a range of adolescent health-risk behaviors earlier in life may be warranted. There are several available and effective alcohol policies and strategies that may also affect bullying and other health-risk behaviors.18,22 Efforts that seek to evaluate implemented strategies across possible health outcomes are sorely needed and may be particularly relevant for the prevention of alcohol use, as well as bullying and other forms of violence, given the strong associations across these factors and also because of possibly shared etiology.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Abigail Hankin MD, MPH

Submission history: Submitted: January 18, 2011; Accepted March 3, 2011.

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem.

Address for Correspondence: Monica H. Swahn, PhD, MPH

College of Health and Human Sciences, Institute of Public Health, Georgia State University

Email: mswahn@gsu.edu

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, et al. Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2094–100. [PMC free article][PubMed]

2. Kaltiala-Heino R, Rimpelä M, Rantanen P, et al. Bullying at school–an indicator of adolescents at risk for mental disorders. J. Adolesc. 2000;23(6):661–74. [PubMed]

3. Glew GM, Fan MY, Katon W, et al. Bullying, psychosocial adjustment, and academic performance in elementary school. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(11):1026–31. [PubMed]

4. Wang J, Iannotti RJ, Nansel TR. School bullying among adolescents in the United States: physical, verbal, relational, and cyber. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(4):368–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

5. Glew GM, Frey KS, Walker WO. Bullying update: are we making any progress? Pediatr Rev.2010;9:e68–74. [PubMed]

6. Craig W, Harel-Fisch Y, Fogel-Grinvald H, et al. A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. Int J Public Health. 2009;54(Suppl2):216–24.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

7. Georgia Department of Education Policy for Prohibiting Bullying, Harassment and Intimidation GA bullying. Available at: http://www.gadoe.org/sia_titleiv.aspx?PageReq=SIABully Last accessed January 17, 2011.

8. Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:739–46. [PubMed]

9. Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. Ten-year prospective study of public health problems associated with early drinking. Pediatrics. 2003;111:949–55. [PubMed]

10. Hingson RW, Heeren T, Jamanka A, et al. Age of drinking onset and unintentional injury involvement after drinking. JAMA. 2000;284:1527–33. [PubMed]

11. Hingson R, Heeren T, Zakocs R, et al. Age of first intoxication, heavy drinking, driving after drinking and risk of unintentional injury among U.S. college students. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:23–31. [PubMed]

12. Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter MR, et al. Early age of first drunkenness as a factor in college students‘ unplanned and unprotected sex attributable to drinking. Pediatrics. 2003;111:34–41.[PubMed]

13. Cho H, Hallfors DD, Iritani BJ. Early initiation of substance use and subsequent risk factors related to suicide among urban high school students. Addict Behav. 2007;32(8):1628–39. [PubMed]

14. Swahn MH, Bossarte RM, Sullivent EE. Age of alcohol use initiation, suicidal behavior, and peer and dating violence victimization and perpetration among high-risk seventh-grade adolescents.Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):297–305. [PubMed]

15. Swahn MH, Bossarte RM. Gender, early alcohol use, and suicide ideation and attempts: findings from the 2005 youth risk behavior survey. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41(2):175–81. [PubMed]

16. Swahn MH, Bossarte RM, Ashby J, et al. Early alcohol use and suicide attempts among middle and high school students: findings from the 2006 Georgia student health survey. Addict Behav.2010;35(5):452–8. [PubMed]

17. Hingson R, Heeren T, Zakocs R. Age of drinking onset and involvement in physical fights after drinking. Pediatrics. 2001;108:872–7. [PubMed]

18. Bonnie RJ, O’Connell ME. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. Reducing underage drinking: a collective responsibility.

19. Office of Applied Studies. Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings (DHHS Publication No. SMA 07-4293, NSDUH Series H-32) Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2007.

20. Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2009.MMWR. 2010;59:SS–5.

21. Chambless C, Marshall ML, Odenat L, et al. Georgia Student Health Survey II: State Report 2006.Available at:http://www.doe.k12.ga.us/DMGetDocument.aspx/GSHS%20II%20State%20Report%20Narrative.pdf?p=6CC6799F8C1371F631F1A16DA0D5351B6B91CEA0B1D38A71FBB48B4A36F2AD54&Type=DLast accessed January 17, 2011.

22. Brewer RD, Swahn MH. Binge drinking and violence. JAMA. 2005;294(5):616–8. [PubMed]

23. Swahn MH, Donovan JE. Alcohol and violence: Comparison of the psychosocial correlates of adolescent involvement in alcohol-related physical fighting versus other physical fighting. Addict Behav. 2006;31:2014–29. [PubMed]

24. Swahn MH, Donovan JE. Predictors of fighting attributed to alcohol use among adolescent drinkers. Addict Behav. 2005;30:1317–34. [PubMed]

25. Swahn MH, Donovan JE. Correlates and predictors of violent behavior among adolescent drinkers. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34(6):480–92. [PubMed]

26. Swahn MH, Simon TR, Hammig BJ, et al. Alcohol consumption behaviors and risk for physical fighting and injuries among adolescent drinkers. Addict Behav. 2004;29(5):959–63. [PubMed]

27. Obot IS, Wagner FA, Anthony JC. Early onset and recent drug use among children of parents with alcohol problems: data from a national epidemiologic survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;65:1–8.[PubMed]

28. Donovan JE. Adolescent alcohol initiation: A review of psychosocial risk factors. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(529):7–18.

29. Hamburger ME, Leeb RT, Swahn MH. Childhood maltreatment and early alcohol use among high-risk adolescents. J Studies Alcohol Drug Use. 2008;69(2):291–5.

30. Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, et al. Who drinks and why? A review of socio-demographic, personality, and contextual issues behind the drinking motives in young people. Addict Behav.2006;31:1844–57. [PubMed]

31. Bossarte RM, Swahn MH. Interactions between race/ethnicity and psychosocial correlates of pre-teen alcohol use initiation among seventh grade students in an urban setting. J Studies Alcohol Drug Use. 2008;69:660–5.

32. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Online: Results for Georgia 2009.

33. Compared with United States 2007. Available at: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/yrbss/ Last accessed January 17, 2011.

34. Bossarte RM, Swahn MH. The Associations between Early Alcohol Use and Suicide Attempts among Adolescents with a History of Major Depression. Addict Behav. 2011 Jan 13; [Epub ahead of print]