| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Keith J. Yablonicky, MD | Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Angeles, CA |

| Stuart P. Swadron, MD | Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Angeles, CA |

A 28-year-old male presented to the emergency department with acute onset of confusion, slurred speech, disequilibrium, and right-sided facial droop. He had no headache, fever, chills, recent trauma, recent travel, or similar symptoms in the past. He was previously healthy with no history of drug, alcohol or tobacco use. His family history and review of systems were unremarkable. Although his vital signs were normal, his mental status fluctuated widely, from completely cogent to having difficulty following basic instructions. He had a slight right-sided facial droop and right upper extremity weakness with pronator drift. His right lower extremity had normal strength and function. His deep tendon reflexes and sensation were intact. His balance was poor and he fell toward his right side. The remainder of his exam was unremarkable.

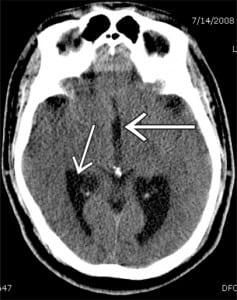

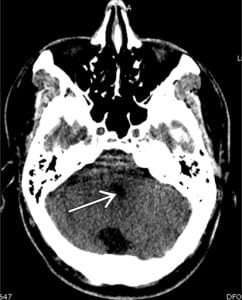

Non-contrast head computed tomography demonstrated hydrocephalus with enlarged lateral and third ventricles, no focal lesions and no hemorrhage (Figure 1). Complete blood count, serum chemistry and coagulation studies were all normal. The patient received consultation from the neurology and neurosurgical services, and was admitted for an MRI and possible ventriculostomy. An MRI confirmed the diagnosis of hydrocephalus but revealed no additional pathology. In the absence of other findings and a normal fourth ventricle (Figure 2), the hydrocephalus in this case appears to be related to acquired stenosis of the aqueduct of Sylvius, the narrow channel of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that connects the third and fourth ventricles.1 It may result from any process that narrows or occludes the flow of CSF, including infections, tumors or hemorrhage. On further review of the patient’s history, it was discovered that he had suffered from bacterial meningitis as a child.2 The patient improved clinically over the next two days and did not require a ventriculostomy. He was discharged with close neurology and neurosurgical follow up.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Sean Henderson, MD

Submission history: Submitted March 24, 2009; Revision Received May 12, 2009; Accepted May 21, 2009

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Stuart P. Swadron, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, LAC+USC Medical Center, Unit #1, Room 1011, 1200 N. State Street, Los Angeles, CA 90033

Email: swadron@usc.edu

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 6th Edition. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Inc; 2006.

2. Baustian GH, McIntire S, Heinzman D. Hydrocephalus MD Consult First Consult August242007. Available at: http://www.mdconsult.com/das/pdxmd/body/169396854-2/0?type=med&eid=9-u1.0-_1_mt_1010369 Accessed March 24, 2009.