| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Grayson W. Armstrong, BA | Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island |

| Allison J. Chen, BA | Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island |

| James G. Linakis, MD, PhD | Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island |

| Michael J. Mello, MD, MPH | Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island |

| Paul B. Greenberg, MD | Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island |

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

ABSTRACT

Introduction

Motor vehicle crashes (MVCs) are a leading cause of injury in the United States (U.S.). Detailed knowledge of MVC eye injuries presenting to U.S. emergency departments (ED) will aid clinicians in diagnosis and management. The objective of the study was to describe the incidence, risk factors, and characteristics of non-fatal motor vehicle crash-associated eye injuries presenting to U.S. EDs from 2001 to 2008.

Methods

Retrospective cross-sectional study using the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System All Injury Program (NEISS-AIP) from 2001 to 2008 to assess the risk of presenting to an ED with a MVC-associated eye injury in relation to specific occupant characteristics, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, disposition, and occupant (driver/passenger) status.

Results

From 2001 to 2008, an estimated 75,028 MVC-associated eye injuries presented to U.S. EDs. The annual rate of ED-treated eye injuries resulting from MVCs declined during this study period. Males accounted for 59.6% of eye injuries (95% confidence interval [CI] 56.2%–63.0%). Rates of eye injury were highest among 15–19 year olds (5.8/10,000 people; CI 4.3–6.0/10,000) and among African Americans (4.5/10,000 people; CI 2.0–7.1/10,000). Drivers of motor vehicles accounted for 62.2% (CI 58.3%–66.1%) of ED-treated MVC eye injuries when occupant status was known. Contusion/Abrasion was the most common diagnosis (61.5%; CI 56.5%–66.4%). Among licensed U.S. drivers, 16–24 year olds had the highest risk (3.7/10,000 licensed drivers; CI 2.6–4.8/10,000).

Conclusion

This study reports a decline in the annual incidence of ED-treated MVC-associated eye injuries. The risk of MVC eye injury is greatest among males, 15 to 19 year olds and African Americans.

INTRODUCTION

Motor vehicle crashes (MVCs) are one of the leading causes of injuries in the United States (U.S.) and impose a large economic burden on the healthcare system.1,2 MVCs present unique eye injury risk factors such as rapid changes in velocity, potential broken glass exposure, airbag deployment, lack of occupant restraint use, and other foreign body exposure.3–8 However, recent epidemiological studies of MVCs have not examined ocular injuries presenting to emergency departments (EDs) in the U.S. (Table 1). A better understanding of the risk factors for MVC-related ocular injuries would aid clinicians in the diagnosis and management of MVC eye injury victims. We describe herein the characteristics of MVC-associated eye injuries presenting to United States (U.S.) EDs.

Table 1. Recent nationwide studies of motor vehicle crash-associated eye injuries in the United States

| Author | Population | Study size (# Eye injuries) | Study design | Variables measured | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armstrong et al (present study) | NEISS-AIP | 221,091,934 (75,028) | Retrospective | Characteristics of eye injuries presenting to EDs, occupant status, occupant gender age race/ethnicity disposition | Injury incidence decreasing over time, Increased risk among 15 to 19 year olds, males, African Americans. Decreased risk among 0 to 4 year olds and among elderly |

| McGwin and Owsley (2005)3 | NASS-CDS | 66,941,420 (1,200,131) | Retrospective | Characteristics of eye injury, airbag deployment status, seatbelt status, occupant status, occupant gender age height weight, vehicle characteristics | Injury incidence increasing over time, greater risk with airbag deployment, increased age, female, crash severity, high ΔV. Decreased risk with heavier weight occupant or seatbelt use |

| Duma et al (2005)5 | NASS-CDS | 2,413,347 (82,405) | Retrospective | Characteristics of eye injury, full-powered vs depowered airbag, seatbelt status, occupant status, occupant height age weight seat position, crash ΔV | Depowered airbags have decreased risk of eye injury, greater risk of injury among driver, increased risk with depowered airbag if greater weight or increased ΔV |

| Duma and Jernigan (2003)15 | NASS-CDS | 12,429,580 (24,605) | Retrospective | Characteristics of orbital fractures, airbag deployment status, seatbelt status, occupant status, occupant gender age height weight, crash ΔV | Airbags decrease incidence and severity of orbital fractures |

| Hansen et al (2003)16 | NASS-CDS | 11,494,824 (289,279) | Retrospective | Characteristics of airbag vs non-airbag injuries, age, dynamic modeling of elderly vs young eye injuries | Eye injury incidence and severity increases with increasing age and associated lens stiffness causes increased stresses in ciliary body |

| Duma et al (2002)4 | NASS-CDS | 10,770,828 (238,263) | Retrospective | Characteristics of eye injury, airbag deployment status, seatbelt status, occupant status, occupant gender age height weight, use of eyewear, crash ΔV | Airbags reduce severity of eye injury but increase rate of corneal abrasions, greater risk of injury among drivers and light weight occupants |

The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System – All Injury Program (NEISS-AIP) and the National Automotive Sampling System – Crashworthiness Data System (NASS-CDS) are United States injury datasets. ΔV represents a change in velocity during a motor vehicle crash.

METHODS

This study received local institutional review committee exemption; review was not indicated for use of the NEISS-AIP database. This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and all federal and state laws.

Data Source

The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System All Injury Program (NEISS-AIP) is a database containing national, weighted, annualized estimates for non-fatal injuries treated in U.S. EDs.9 Data from 66 of the 100 NEISS hospitals with both trauma and non-trauma center EDs are included in the NEISS-AIP. These hospitals each have an ED with a minimum of six beds, are open 24 hours per day, and are used as a nationally representative, stratified probability sample of the roughly 5,000 hospitals in the U.S. with an ED of the same parameters. Each year, the NEISS-AIP collects data on approximately 500,000 non-fatal injury- and consumer-related cases. The NEISS-AIP defines non-fatal injuries as bodily harm resulting from severe exposure to an external force, substance, or submission.

Hospitals in the NEISS-AIP network provide data from injury-related ED cases daily. Each case report consists of coded variables describing characteristics of the injury, including demographic information, disposition upon ED discharge, principal diagnoses, primary body part affected, and the locale where the injury took place. Coders only report ED injury cases to the NEISS-AIP if specific mechanistic, diagnostic, and mortality criteria are met.10 NEISS-AIP quality assurance coders code the cause, assault-relatedness, and transportation- and traffic-relatedness of each injury. The NEISS-AIP defines traffic-related injuries as those precipitating from MVCs occurring on a public highway, street, or road as opposed to any other location. Causes of injury are classified into major external cause and intent-of-injury groupings from the International Classification of Disease (ICD) 9-CM. We chose this national dataset over other potential databases due to its focus on ED-injury case data, which our study sought to address.

Data Analysis

This was a retrospective cross-sectional study using the NEISS-AIP database to examine eye injuries sustained by occupants of MVCs treated in EDs from 2001 through 2008 (the most recent year data were available at time of analysis).9

The inclusion criteria for this study were cases where the “eyeball” was identified as the primary body part injured and where “motor vehicle occupant” (MV-occupant) was identified as the precipitating cause of injury. Motorcycle and pedestrian injuries were excluded from our study.

We derived national injury estimates using the sample weights representing the inverse probability of selection for each case seen in the 66 NEISS-AIP hospitals. Weighted counts of injuries serve as representative numbers for national injuries and are derived from the NEISS-AIP dataset. We estimated projected incidences of injury along with their associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using STATA SE, version 10.0 (STATA Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). The program’s Survey commands (svy) are capable of accounting for the sampling weight structure present in the NEISS-AIP database. The types, dispositions, and mechanisms of eye injuries, as well as the race and ethnicity of patients, were tabulated. We created figures using Microsoft Excel, version 14.2.3. The program’s ‘Add Trendline…’ linear regression function was used to create associated trendlines.

We determined rates of injury among the general population using national population estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau.11 The estimated population data for July 1, 2004, and July 1, 2005 were averaged, yielding a population estimate for January 1, 2005, the midpoint of our study. We used U.S. Census Bureau data for annual as well as race and ethnicity population estimates where appropriate.

We determined rates of injury specifically among drivers in MVCs using both NEISS-AIP national estimates of MVC-related eye injuries among drivers and U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration estimates of licensed drivers in the U.S.12–14 The NEISS-AIP records the driver (and passenger occupant) status of ED-treated injury cases. We averaged the estimated U.S. licensed driver population data for 2004 and 2005, yielding an estimate for January 1, 2005, the midpoint of our study.

RESULTS

From 2001 to 2008, an estimated 221,091,934 (95% confidence interval [CI] 192,415,800–249,768,068) ED visits due to non-fatal injury occurred in the U.S., of which 21,499,257 (CI 17,729,204–25,269,310), or 9.7%, were due to MVCs (Table 2). An estimated 75,028 (CI 62,103–87,953) cases, representing 0.3% of MVC ED visits, involved an injury to the eyeball. Motor vehicle crash patients presented to EDs at an estimated rate of 730.2 cases per 10,000 people (CI 602.2–858.3/10,000), while MVC-associated eye injuries presented to EDs at an estimated rate of 2.5 cases per 10,000 people (CI 2.1–3.0/10,000). Males presented to EDs more often with MVC eye injuries (59.6%; CI 56.2%–63.0%).

Table 2. Demographics of United States emergency department visits from 2001–2008, including motor vehicle crash and eye injury data.

| Characteristic | Sample size | National estimates (95% Confidence Interval)a | Percent of ED visits | Rate per 10,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total ED Visits | ||||

| Male | 2,045,386 | 121,597,423 (105,544,620–137,650,226) | 55.0% | 8,394.8 |

| Female | 1,627,955 | 99,450,992 (86,848,538–112,053,445) | 45.0% | 6,650.0 |

| Unknown | 759 | 43,519 (22,642–64,397) | 0.0002% | – |

| Total | 3,674,100 | 221,091,934 (192,415,800–249,768,068) | 100% | 7,509.9 |

| Total MVC ED cases | ||||

| Male | 174,335 | 9,734,788 (8,034,67–11,434,889) | 45.3% | 672.1 |

| Female | 204,542 | 11,760,691 (9,661,377–13,860,004) | 54.7% | 786.4 |

| Unknown | 85 | 3,778 (1,603–5,953) | 0.0002% | – |

| Total | 378,962 | 24,499,257 (17,729,204–25,269,310) | 100% | 730.3 |

| MVA eye Injury cases | ||||

| Male | 763 | 44,702 (36,534–52,870) | 59.6% | 3.1 |

| Female | 551 | 30,326 (24,547–36,085) | 40.4% | 2.0 |

| Total | 1,314 | 75,028 (62,103–87,953) | 100% | 2.5 |

ED, emergency department, MVC, motor vehicle crash, MVA, motor vehical accident

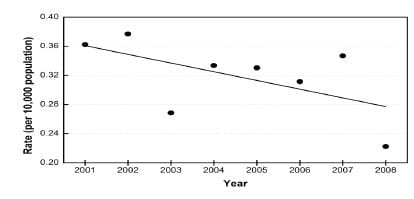

The estimated annual incidence of MVC-associated eye injuries presenting to EDs are presented in the figure. The annual estimated rate of MVC-associated eye injuries varied substantially from year to year, though a distinct decreasing trend was observed. A 20% decrease was also seen in the nationally estimated number of ED visits from all MVC injuries over the eight-year period (a reduction from 100.3/10,000 people to 79.8/10,000 people).

Figure

Rates of eye injuries due to motor vehicle crashes treated in United States emergency departments.

*National estimates derived utilizing NEISS-AIP weighted frequencies. Rate of injury calculated using national population estimates from US Bureau of the Census, January, 2005. Trendline created using Microsoft Excel’s ‘Add Trendline…’ linear regression function.

The age breakdown of ED-treated MVC-associated eye injury patients is detailed in Table 3. The estimated rate of MVC eye injuries peaked in the 15- to 19-year-old age group (5.8/10,000; CI 4.3–6.0/10,000) and then decreased with increasing age (not presented in table). Children less than five years of age had the lowest estimated rate of MVC eye injuries (0.8/10,000; CI 0.4–1.2/10,000).

Table 3. Age breakdown of motor vehicle crash-associated eye injuries treated in U.S. emergency departments, 2001–2008.

| Age | Sample size | National estimates (95% Confidence Interval)a | Percent of ED visits | Rate per 10,000 peopleb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 to 19 | 440 | 20,773 (16,056–25,489) | 27.7% | 2.5 |

| 20 to 29 | 310 | 18,152 (14,792–21,512) | 24.2% | 4.5 |

| 30 to 49 | 382 | 23,840 (18,435–29,246) | 31.8% | 2.8 |

| 50 to 69 | 146 | 9,964 (7,720–12,208) | 13.3% | 1.7 |

| 70 + | 35 | 2,278 (1,240–3,317) | 3.0% | 0.9 |

| Unknown | 1c | 21.4 (0–64.2) | 0.03% | – |

| Total | 1,314 | 75,028 (62,103–87,953) | 100% | 2.5 |

ED, emergency department

Table 4 details the estimated rate of ED presentation of MVC-associated eye injuries per licensed driver in the U.S. The rate of eye injury was highest in the 16 to 24 age group (3.7/10,000 licensed drivers; CI 2.6–4.8/10,000) and decreased with increasing age; in the 65 to 74 age group, however, the number of eye injuries reported was too low to provide stable estimates.

Table 4. Rates of motor vehicle crash-associated eye injuries among licensed drivers in the U.S.

| Age | Sample size | National estimates (95% Confidence Interval)a | Rate per 10,000 licensed driversd |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16–24 | 160 | 9,656 (6,839–12,472) | 3.7 |

| 25–34 | 134 | 9,181 (6,853–11,509) | 2.5 |

| 35–44 | 104 | 6,407 (4,303–8,511) | 1.6 |

| 45–54 | 85 | 6,435 (4,499–8,371) | 1.6 |

| 55–64 | 42 | 3,013 (1,815–4,211) | 1.1 |

| 65–74 | 10c | 601 (122–1,081) | 0.4 |

| 75+ | 8c | 759 (97.4–1,421) | 0.6 |

| Total | 547 | 36,222 (28,553–43,891) | 1.8 |

We list race and ethnicity data for MVC-associated eye injury cases in Table 5. They are presented as percentages of ED cases where race and ethnicities were known and recorded in the NEISS-AIP. The white non-Hispanic population had the greatest estimated incidence of eye injuries during our study period (59.6%; CI 45.8%–73.4%). Taking U.S. race and ethnicity population estimates into account and excluding the ‘other non-Hispanic’ category, the estimated rate of MVC eye injury was highest among African Americans (4.5/10,000; CI 2.0–7.1/10,000) and was lowest for Asian non-Hispanics (0.9/10,000; CI −0.3 to 2.0/10,000).

Table 5. Race and ethnicity breakdown of motor vehicle crash-associated eye injuries treated in U.S. emergency departments, 2001–2008.

| Race/ethnicity | Sample size | National estimates (95% Confidence Interval)a | Percent of ED visits (excluding unknown) | Rate per 10,000 Peopleb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Non-Hispanic (NH) | 494 | 33,919 (23,997–43,842) | 45.2% (59.6%) | 3.1 |

| African American | 338 | 16,284 (7,057–25,512) | 21.7% (28.6%) | 4.5 |

| Hispanic | 105 | 4,474 (2,153–6,796) | 6.0% (7.9%) | 1.1 |

| Asian NH | 18c | 1,050 (−344–2,444) | 1.4% (1.8%) | 0.9 |

| American Indian NH | 8c | 911 (−724–2,546) | 1.2% (1.6%) | 4.1 |

| Other NH | 12c | 266 (−7.96–540) | 0.4% (0.5%) | 6.6 |

| Unknown | 339 | 18,123 (8,056–28,190) | 24.2% | – |

Further MVC victim- and crash-characteristics (diagnosis, disposition, occupant status) are presented in Table 6. The most common diagnoses were contusion/abrasion (61.5%; CI 56.5–66.4%), foreign body (19.7%; CI 15.5–23.9%), and hemorrhage (4.1%; CI 2.6–5.6%). The majority of patients were treated and released from the ED (94.9%; CI 92.8–97.0%). Drivers suffered the majority of MVC eye injuries (62.2% excluding unknown; CI 58.3%–66.1%) as compared to passengers.

Table 6. Patient and crash characteristics of motor vehicle crash-associated eye injuries treated in U.S. emergency departments, 2001–2008.

| Characteristic | Sample size | National estimates (95% Confidence Interval)a | Percent of ED visits (excluding unknown) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | |||

| Contusion/abrasion | 843 | 46,114 (36,592–55,636) | 61.5% |

| Foreign body | 227 | 14,801 (11,632–17,971) | 19.7% |

| Hemorrhage | 58 | 3,095 (1,658–4,531) | 4.1% |

| Laceration | 42 | 2,712 (1,397–4,027) | 3.6% |

| Conjunctivitis | 34 | 2,219 (1,108–3,331) | 3.0% |

| Hematoma | 14c | 1,032 (123–1,941) | 1.4% |

| Burn chemical | 7c | 693 (26.5–1,359) | 0.9% |

| Puncture | 4c | 274 (−51.7–599) | 0.4% |

| Burn not specified | 2c | 126 (−108–359) | 0.2% |

| Strain/sprain | 1c | 119 (−119–357) | 0.2% |

| Burn thermal | 1c | 21.4 (−21.5–64.2) | 0.03% |

| Other | 81 | 3,823 (2,400–5,246) | 5.1% |

| Disposition | |||

| Treated/released | 1,248 | 71,201 (58,745–83,656) | 94.9% |

| Hospitalized/transferred/observed | 59 | 3,576 (1,891–5,260) | 4.8% |

| Othere | 7c | 252 (−21–525) | 0.3% |

| Occupant status | |||

| Driver | 547 | 36,222 (28,553–43,891) | 48.3% (62.2%) |

| Passenger | 453 | 21,812 (17,069–26,556) | 29.1% (37.5%) |

| Other specified | 3c | 162 (−82–407) | 0.2% (0.3%) |

| Unknown/unspecified | 311 | 16,831 (12,743–20,919) | 22.4% |

| Total | 1,314 | 75,028 (62,103–87,953) | 100% |

The rates of elderly MVC eye injuries were decreased across all diagnostic categories except for ‘hemorrhage,’ though the number of eye injuries reported per diagnosis in each age category was often too low to provide stable estimates (data not presented).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to characterize and identify risk factors associated with ED-treated nonfatal MVC-associated eye injuries using a national ED database. This study underscores the importance of several trends that differ from previous literature on MVC-associated eye injuries: a recent decline in the incidence of ED-treated injuries, a decreased risk among the elderly, and an increased risk among males, adolescents (age 15 to 19) and African Americans.3–5,15–16

We found that the incidence of ED-treated MVC-associated eye injuries decreased during our study period. In contrast, McGwin and colleagues3 cited an increasing trend in the risk of eye injuries from MVCs; however, their study did not focus specifically on ED-treated injuries, surveyed a different time period (1988–2001), and used a different injury database. The mandated inclusion of dual front-seat airbags in passenger cars during their study period resulted in higher rates of minor MVC-eye injuries (i.e. corneal abrasions) despite a simultaneous reduction in severe MVC-eye injuries.4,5,17 Advanced frontal airbag systems, mandated in model year 2006, represented an improvement over previous airbag technologies in their ability to sense occupant size, seat position, seatbelt use, and crash severity so as to deploy airbags at an appropriate level of power.18,19 The advanced airbags may have decreased MVC eye-injury risk in our study period.

An estimated 9,280 to 11,600 eyeball injuries occur in the U.S. as a result of MVCs annually.3 Our annual incidence of ED-treated MVC eyeball injuries fell within this predicted range with the exception of our 2003 (7,793 injuries) and 2008 (6,769 injuries) data. Hence, our findings suggest that the majority of MVC eyeball injuries occurring in the U.S. were seen in EDs.

Males in our study were at the greatest risk of suffering an ED-treated MVC eye injury, which is contrary to another MVC eye injury study but is consistent with males being injured more often in MVCs.3,14 The increased risk of MVC injury among males has been linked to a higher incidence of loss-of-control crashes and a greater incidence of speeding.20 Crashes of increased severity and with larger changes in velocity have been associated with an increased risk of MVC eye injury.5

While both drivers and passengers of vehicles involved in MVCs may sustain eye injuries, drivers were treated in EDs at a higher rate during our study period. This trend is echoed in the existing MVC eye injury literature.3–5,21 After accounting for the relative abundance of drivers at risk of MVCs when compared to passengers, however, the relative risk of MVC-associated eye injury was found to be the same for both drivers and passengers.3

Adolescents aged 15 to 19 had the highest rate of MVC-associated eye injuries presenting to EDs. Among licensed drivers, those in the 16- to 24-year-old age group were found to have the highest rate of MVC eye injury visits. Previous studies have identified both young drivers (16 to 35 years of age) and older drivers (>43 years of age and >66 years of age) as being at the greatest risk of MVC eye injury.3,16,22 Our results may be due to the increased rate of MVC among adolescents and young adults, which has been attributed to driving inexperience in the youngest age groups, an increased likelihood of undertaking risky driving practices, and a decreased use of seat belts.23–27

Researchers have hypothesized that mechanical changes that occur in the aging eye predispose older patients to an increased risk of MVC-associated eye injury and to different injury diagnoses and outcomes.16,28 However, we found that after the age of 18, the risk of presenting to an ED with a MVC eye injury decreased with increasing age. Indeed, the elderly population had the lowest rate of MVC eye injury per person among adults. The elderly also had the lowest rate of MVC eye injury across nearly all diagnostic categories. Several explanations may account for our results. First, elderly persons increasingly forego driving motor vehicles voluntarily as they age.29–30 Second, many states require elderly persons to undergo in-person license renewal as well as visual acuity and driving testing, which allows states to limit licensing of high-risk elderly drivers.31–33 Lastly, elderly patients have the highest rate of seat belt use, a behavior known to decrease eye injury risk.7,34 These findings are especially important in light of the rapidly increasing population of elderly individuals in the U.S.35

Our study found that African Americans had the highest rate of ED-treated MVC eye injuries. Praevious studies have found that African Americans use seat belts less often than other racial and ethnic populations, a practice shown to increase the risk of MVC eye injury.3,7,36

Similar to previous studies, we identified corneal abrasion/contusion, foreign body and hemorrhage as the most common ED-treated ocular diagnoses resulting from MVCs, especially after the deployment of an airbag.3–7,37–40 While the NEISS-AIP is unable to provide detailed information regarding foreign body and hemorrhage diagnoses, existing case reports and reviews document the injury variability within these broad diagnostic categories.40–44

LIMITATIONS

The findings reported in this study should be considered in light of several limitations. First and foremost, the NEISS-AIP database only reports injuries presenting to U.S. EDs, which may skew our results toward more serious eye injuries. It is unknown what proportion of MVC-associated eye injuries present to non-ED healthcare settings, but our study suggests that the majority of MVC-related eye injuries are seen in EDs. Second, the severity, visual outcomes, and long-term morbidities of injuries were not available in the NEISS-AIP database for evaluation. Third, injuries to the ocular adnexal tissues were coded as injuries to the “face” within the NEISS-AIP database, making it difficult to study these injuries specifically. Fourth, the NEISS-AIP is more likely to record cases of isolated ocular trauma as opposed to eye injury cases that occur as a secondary diagnosis or that occur during multi-trauma, unless the principle multi-trauma diagnosis is determined to affect the eyeball. This may result in an underestimation in both the number of and the severity of MVC eye injuries presenting to EDs in our study. Similarly, victims whose injuries were coded in the NEISS-AIP as affecting “25–50 percent body” or “all body parts,” instead of “eyeball” may have sustained eye injuries, but we did not include these cases in our study. Additionally, the NEISS-AIP does not record the specific anatomic area of the eye affected by injury (i.e. cornea, vitreous, retina). Lastly, using the entire U.S. population as the denominator in rate calculations results in an underestimation of true incidence of injury, as this calculation assumes that the entire population is a vehicle occupant and that all individuals are at equal risk of MVC eye injury.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we report a decline in the rate of ED-treated MVC eye injuries in the U.S. and identify an increased risk among males, 15 to 19 year olds, and African Americans. Understanding and further investigating risk factors associated with ED-treated MVC eye injuries will aid emergency medicine clinicians in diagnosis and management, and should guide future prevention strategies.

Footnotes

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Paul B. Greenberg, MD, Division of Ophthalmology, Rhode Island Hospital, 1 Hoppin Street, Suite 200, Providence, RI 02903. Email: paul_greenberg@brown.edu 9 / 2014; 15:693 – 700

Submission history: Revision received December 21, 2013; Submitted April 10, 2014; Accepted May 5, 2014

Conflicts of Interest: By the West JEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1 . 10 leading causes of nonfatal unintentional injury, United States – 2007, all races, both sexes, disposition: all cases. ;

2 . Save lives, save dollars: prevent motor vehicle-related injuries. 2010; :1-2

3 McGwin G, Owsley C Risk factors for motor vehicle collision-related eye injuries. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005; 123:89-95

4 Duma SM, Jernigan MV, Stitzel JD The effect of frontal air bags on eye injury patterns in automobile crashes. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002; 120:1517-1522

5 Duma SM, Rath AL, Jernigan MV The effects of depowered airbags on eye injuries in frontal automobile crashes. Am J Emerg Med. 2005; 23:13-19

6 Ghoraba H Posterior segment glass intraocular foreign bodies following car accident or explosion. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002; 240:524-528

7 Rao SK, Greenberg PB, Filippopoulos T Potential impact of seatbelt use on the spectrum of ocular injuries and visual acuity outcomes after motor vehicle accidents with airbag deployment. Ophthalmology. 2008; 115:573-576 e1

8 Nanda SK, Mieler WF, Murphy ML Penetrating ocular injuries secondary to motor vehicle accidents. Ophthalmology. 1993; 100:201-207

9 . National electronic injury surveillance system all injury program. 2007;

10 Armstrong GW, Kim JG, Linakis JG Pediatric eye injuries presenting to United States emergency departments: 2001–2007. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013; 251:629-636

11 . Population estimates. 2012;

12 . Our nation’s highways: 2010. 2010;

13 . Distribution of licensed drivers-2010 by sex and percentage in each age group and relation to population. 2011;

14 . Fatality analysis reporting system (FARS) encyclopedia. 2012;

15 Duma SM, Jernigan MV The effects of airbags on orbital fracture patterns in frontal automobile crashes. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003; 19:107-111

16 Hansen GA, Stitzel JD, Duma SM Incidence of elderly eye injuries in automobile crashes: the effects of lens stiffness as a function of age. Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automot Med. 2003; 47:147-163

17 . Federal motor vehicle safety standards and regulations: summary description of the federal motor vehicle safety standards (title 49 code of federal regulations part 571) standard no. 208. 1999;

18 . Advanced frontal air bags. 2012;

19 . Fifth/sixth report to Congress: effectiveness of occupant protection systems and their use, DOT-HS-809-442. 2001;

20 Tavris DR, Kuhn EM, Layde PM Age and gender patterns in motor vehicle crash injuries : importance of type of crash and occupant role. Accid Anal Prev. 2001; 33:167-172

21 Huelke DF, O’Day J, Barhydt WH Ocular injuries in automobile crashes. J Trauma. 1982; 22:50-52

22 Kuhn F, Collins P, Morris R Epidemiology of motor vehicle crash-related serious eye injuries. Accid Anal Prev. 1994; 26:385-390

23 . Statistical abstract of the United States: 2012. 2012;

24 Sarkar S, Andreas M Acceptance of and engagement in risky driving behaviors by teenagers. Adolescence. 2004; 39:687-700

25 Ivers R, Senserrick T, Boufous S Novice drivers’ risky driving behavior, risk perception, and crash risk: findings from the DRIVE study. Am J Public Health. 2009; 99:1638-1644

26 Hassan HM, Abdel-Aty MA Exploring the safety implications of young drivers’ behavior, attitudes and perceptions. Accid Anal Prev. 2013; 50:361-370

27 . Adult seat belt use in the US. 2011;

28 Stitzel JD, Hansen GA, Herring IP Blunt trauma of the aging eye. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005; 123:789-794

29 Marottoli RA, Ostfeld AM, Merrill SS Driving cessation and changes in mileage driven among elderly individuals. J Gerontol. 1993; 48:S255-260

30 Rosenbloom S Mobility of the elderly good news and bad news: transportation in an aging society: a decade of experience: technical papers and reports from a conference. . 2004; 27:3-21

31 Grabowski DC, Campbell CM, Morrisey MA Elderly licensure laws and motor vehicle fatalities. JAMA. 2004; 291:2840-2846

32 Levy DT, Vernick JS, Howard KA Relationship between driver’s license renewal policies and fatal crashes involving drivers 70 years or older. JAMA. 1995; 274:1026-1030

33 McGwin G, Sarrels SA, Griffin R The impact of a vision screening law on older driver fatality rates. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008; 126:1544-1547

34 Vital signs: nonfatal, motor vehicle–occupant injuries (2009) and seat belt use (2008) among adults — United States. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011; 59:1681-1686

35 . Table 12: projections of the population by age and sex for the United States: 2010 to 2050. 2012;

36 Vivoda JM, Eby DW, Kostyniuk LP Differences in safety belt use by race. Accid Anal Prev. 2004; 36:1105-1109

37 Corazza M, Trincone S, Virgili A Effects of airbag deployment: lesions, epidemiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004; 5:295-300

38 Scarlett A, Gee P Corneal abrasion and alkali burn secondary to automobile air bag inflation. Emerg Med J. 2007; 24:733-734

39 Duma SM, Kress TA, Porta DJ Airbag-induced eye injuries: a report of 25 cases. J Trauma. 1996; 41:114-149

40 Sastry SM, Copeland RA, Mezghebe H Retinal hemorrhage secondary airbag-related ocular trauma. J Trauma. 1995; 38:582

41 Pearlman JA, Au Eong KG, Kuhn F Airbags and eye injuries: epidemiology, spectrum of injury, and analysis of risk factors. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001; 46:234-242

42 Kivlin JD, Currie ML, Greenbaum VJ Retinal hemorrhages in children following fatal motor vehicle crashes: a case series. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008; 126:800-804

43 Ball DC, Bouchard CS Ocular morbidity associated with airbag deployment: a report of seven cases and a review of the literature. Cornea. 2001; 20:159-163

44 Ahmad AZ, Ayad F, Trobe JD Penetrating orbital injury by automobile wiper-control stalk. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000; 118:1701-1703