| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Peter Moffett, MD | Madigan Army Medical Center, Tacoma, WA |

| Gregory Moore, MD, JD | Madigan Army Medical Center, Tacoma, WA |

ABSTRACT

The true meaning of the term “the standard of care” is a frequent topic of discussion among emergency physicians as they evaluate and perform care on patients. This article, using legal cases and dictums, reviews the legal history and definitions of the standard of care. The goal is to provide the working physician with a practical and useful model of the standard of care to help guide daily practice.

INTRODUCTION

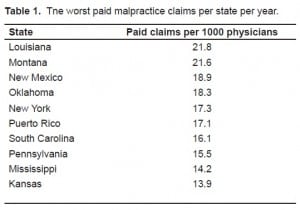

The concept of “the standard of care” is often discussed among physicians, and yet the legal definition of this term is frequently not understood. Emergency physicians are on the front lines of medicine and are frequently involved in medical malpractice cases. It is estimated that 7–17 malpractice claims are filed per 100 physicians every year.1,2 States vary in the number of these claims that result in payment (Table 1).3 Thus it is important to know how the legal system defines the standard of care, and to what standards we as physicians are being held. A chronological approach to the evolving definition of the standard of care through legal history will help to understand the current concept and nuances of the term.

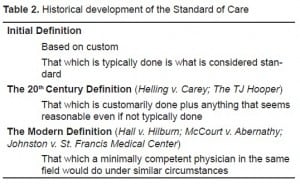

Negligence, in general, is legally defined as “the standard of conduct to which one must conform… [and] is that of a reasonable man under like circumstances.”4 In law, medical malpractice is considered a specific area within the general domain of negligence. It requires four conditions (elements) be met for the plaintiff to recover damages. These conditions are: duty; breach of duty; harm; and causation. The second element, breach of duty, is synonymous with the “standard of care.” Prior to several important cases in the 1900s, the standard of care was defined by the legal concept of “custom.” As quoted in the 1934 case of Garthe v. Ruppert, when “certain dangers have been removed by a customary way of doing things safely, this custom may be proved to show that [the one charged with the dereliction] has fallen below the required standard.” 5 Put another way, if others in the business are commonly practicing a certain way that eliminates hazards, then this practice can be used to define the standard of care. A jury still needed to decide, however, whether this “custom” was reasonable and whether the deviation from this “custom” was so unreasonable as to cause harm.

EARLY LEGAL CASES: THE BAD NEWS

Two cases changed the legal definition of the standard of care as it is applied in medical malpractice law today. The first case had nothing to do with medicine, but rather a tugboat. The case of The T.J. Hooper in 1932 helped to alter how the legal profession thought about custom and the standard of care. In this case, the owner of the tugboat T.J. Hooper was sued for the value of two barges. The tugboat had been caught in a storm and the two barges it was transporting sunk. The owners of the barges charged that the T.J. Hooper was unsafe for duty at sea as it did not have a radio receiver to review important storm warnings. In addition, they charged that it was “customary” for tugboats to have this radio receiver. They claimed that if the T.J. Hooper had a radio, they could have been warned of the storm and avoided it. In reviewing the case during appeal, Justice Learned Hand ruled in favor of the barge owners; however, he did not do so based on custom. He indicated that it was not in fact customary for tugboats to be outfitted with the receivers, but that since the practice was reasonable, the owners of the T.J. Hooper could be help liable for damages. He stated, “In most cases reasonable prudence is in fact common prudence; but strictly it is never its measure; a whole calling may have unduly lagged in the adoption of new and available devices. It never may set its own tests, however persuasive be its usages. Courts must in the end say what is required; there are precautions so imperative that even their universal disregard will not excuse their omission.” 6 In other words, if there is a practice that is reasonable but not universally “customary” it may still be used as a measure of the standard of care.

The case of The T.J. Hooper set the stage for an important trial in medical malpractice that occurred in 1974. In the case of Helling v. Carey, the plaintiff (Helling) sued her ophthalmologist (Carey) for the loss of her eyesight due to glaucoma. The defendant won both during the original trial and the appeal, but when the case made it to the Supreme Court of Washington State the verdict was overturned in favor of the plaintiff. During the initial trials, the expert witnesses indicated that as the patient was under the age of 40 and the incidence of glaucoma in this group was only one in 25,000, that it was not the standard to test patients under 40 with tonometry. The Supreme Court decided, however, that the test was inexpensive and harmless, and should have been offered to the patient. Justice Hand’s decision in The T.J. Hooper case was quoted in the decision.7

The case of Helling v. Carey set a worrisome precedent for medical malpractice cases. The court essentially ruled that even though the customary practice at the time was followed, the physician was still liable. They cited the case of The T.J. Hooper and also referenced a decision by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1903 that stated,”what usually is done may be evidence of what ought to be done, but what ought to be done is fixed by a standard of reasonable prudence, whether it usually is complied with or not.” 8 These two cases legally established that while great weight is given to customary practices with regard to the standard of care, custom is not the definitive factor in determining negligence. In essence, the two cases suggest that what is commonly done (i.e. custom) may not be enough, and that there are some things that may not be standard, but are still reasonable for the physician to perform. Unfortunately for the physician, these cases suggest it is up to the legal profession and the jury, and not the medical profession, to decide what is “reasonable” and “unreasonable.” In fact, subsequent studies have found that Helling v. Carey has changed the practice of offering tonometry to all patients with subsequent increase in cost and no change in morbidity.9 Following the ruling in Helling v Carey, there was an outcry from physicians. The medical profession as a whole seemed to be asking, “How much is enough?”

The ruling in Helling v Carey prompted state legislatures to pass statutes that defined the standard of care in their jurisdiction. The state of Washington was the first to pass this type of legislation, when they stated that the standard of care is not met when “the defendant or defendants [fail] to exercise that degree of skill, care and learning possessed by other persons in the same profession…”10

MODERN CASES: THE GOOD NEWS

The good news for practicing physicians is that in more recent cases there appears to be an effort to ensure that jurors understand that the standard of care does not mean perfection in practice. While old cases in law tend to be more powerful as they have stood the test of time, these more recent cases help show a trend toward keeping jury expectations realistic.

In the 1985 case of Hall v. Hilbun, a patient (Mrs. Hall) presented to her physician for abdominal pain. Dr. Hilbun, a general surgeon, was consulted and operated on the patient for a small bowl obstruction. He observed the patient in the recovery room and left for the night. Details from the case indicate that there were abnormal vital signs, and Mrs. Hall had pain throughout the night, but Dr. Hilbun was not notified. She died of respiratory failure in the morning. During the night, Dr. Hilbun had been notified about another patient, but he did not check up on Mrs. Hall. In addition, his orders never indicated for what things he should be called by the nursing staff. Initially he won the case because the testimony of two witnesses that discussed the national standard of care for a surgeon was excluded. On appeal, however, Dr. Hilbun was found liable as their testimony was allowed. Even though the physician lost in this case, the court’s discussion was very important in defining the standard of care in the modern era. Chief Justice C.J. Robertson stated:

“Medical malpractice is a legal fault by a physician or surgeon. It arises from the failure of a physician to provide the quality of care required by law. When a physician undertakes to treat a patient, he takes on an obligation enforceable at law to use minimally sound medical judgment and render minimally competent care in the course of services he provides. A physician does not guarantee recovery… A competent physician is not liable per se for a mere error of judgment, mistaken diagnosis or the occurrence of an undesirable result.” 11

In this case, Dr. Hilbun did not provide “minimally competent care,” but the good news from a physician’s standpoint is that the law only requires “minimal competence.” The care does not even have to be “average,” which makes sense; otherwise, 50% of all medical care would be malpractice by definition.

A second case with similar outcomes occurred in 1995. In the case of McCourt v. Abernathy the physicians again lost due to their substandard care. Mrs. McCourt presented for several complaints over the course of three days but was found to have an infection on her finger from a pin stick while working in manure. Over the course of these three days, she was seen by Dr. Abernathy and his partner Dr. Clyde who simply cleaned the wound. When she became increasingly ill, they gave her oral antibiotics, but she subsequently became septic. An internist who was consulted diagnosed septicemia, and the patient died despite aggressive care. Again, the physicians acted below the standard of care, but the trial judge gave an important set of instructions to the jury. He stated:

“The mere fact that the plaintiff’s expert may use a different approach is not considered a deviation from the recognized standard of medical care. Nor is the standard violated because the expert disagrees with a defendant as to what is the best or better approach in treating a patient. Medicine is an inexact science, and generally qualified physicians may differ as to what constitutes a preferable course of treatment. Such differences due to preference…do not amount to malpractice.

I further charge you that the degree of skill and care that a physician must use in diagnosing a condition is that which would be exercised by competent practitioners in the defendant doctors’ field of medicine….

Negligence may not be inferred from a bad result. Our law says that a physician is not an insurer of health, and a physician is not required to guarantee results. He undertakes only to meet the standard of skill possessed generally by others practicing in his field under similar circumstances.”12

Again, the judge re-enforced that the care provided by a physician be minimally competent, may differ from the care of other physicians and that a bad outcome does not mean that the standard of care was not met.

A final case that helped define the modern definition of the standard of care is Johnston v St. Francis Medical Center from 2001.13 In this case, a 79-year-old male who presented with abdominal complaints was evaluated with radiographs and labs, but his examination was equivocal. Two physicians examined him during the course of the day and found him to be in mild distress. Additional studies to include computed tomography and ultrasound were ordered, but the patient became hypotensive and was sent to the intensive care unit (ICU). The ICU physician thought he might have an aortic aneurysm, which was confirmed during laparotomy. The patient died in the operating room. The plaintiffs argued that the physicians should have diagnosed the aneurysm earlier. All of the experts, except one, in the case indicated this was a difficult diagnosis. The court ruled in favor of the physicians. More importantly however; the court made it clear that while the aneurysm was obvious on radiograph and labs once the diagnosis was made, hindsight can not be used for evaluating the conduct and judgment of the physician. In this case the diagnosis of aneurysm was “possible” but difficult enough that missing the diagnosis did not amount to not providing the standard of care. This is in sharp contrast to the prior case of Helling v. Carey.

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES AND THE STANDARD OF CARE

A brief discussion on the use of clinical practice guidelines (CPG) as defining the standard of care is warranted. Extensive reviews of the subject are available for the interested reader.9,14–16 Several court cases have addressed the use of CPGs, and currently there is no set standard for how these documents are used in court cases. Some courts allow more liberal use of the CPGs, and others require more scrutiny as to the scientific validity of the CPG before it is admitted. Normally a document like a CPG would be considered “hearsay” in the courts, as the author is not available to testify or to allow for cross-examination. However, the court cases dealing with CPG use have suggested that if the guidelines are of some scientific validity, that they may be used as “learned treatises” and bypass the hearsay rule. CPGs may be used to lend credence to an expert witness, to impeach an expert witness, to defend a physician for following the document as the standard of care, or to suggest physician deviance from the document as deviance from the standard of care. In the end, an explanation by an expert as to why a CPG is indicative or not indicative of the standard of care goes a long way in a court case. When one side uses a CPG in a court case, it is up to the opposing side to ensure that the jury is given adequate explanation as to why this may or may not actually represent the standard of care. This is a continually evolving topic and is currently dealt with on a case-by-case basis. Now recognizing the complicated issues that arise with formulation of CPGs, it would seem optimal that committees who develop these guidelines should allow flexibility, include multiple sources of scientific merit, and not be dependent on the opinion of a relatively small panel. In addition, if clear evidence is sparse, this should be openly acknowledged in the formation of the guideline.

SUMMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In conclusion, the concept of the standard of care has evolved over the years and will continue to change as legal theory in this area develops. Hopefully this will allow for increased certainty and clarity, which is the stated goal of all laws. The bad news is that there are several important cases where the suggestion is that even if a practice is not the standard, if it is reasonable, a physician can be found culpable for not pursuing that course of action. The good news for physicians is that in more recent cases the courts have frequently upheld that the standard of care is what a minimally competent physician in the same field would do in the same situation, with the same resources. These recent cases also note that bad outcomes are to be expected, and all entities can not be expected to be diagnosed. Finally, clinical practice guidelines are being used more frequently in court cases as support for the standard of care; however, their acceptance and uses are continually changing and decided on a case-by-case basis (Table 2).

Emergency physicians should be aware of these landmark cases that define the standard of care. In addition, physicians should be familiar with the content of various clinical practice guidelines so that one may practice by them, or document reason for deviating from them. Each state will also have statues that define malpractice in very specific terms. Physicians should review the relevant laws based on the state they practice in. By practicing with these concepts in mind, an emergency physician can feel more confident in daily practice, and when faced with a malpractice action. With this basic knowledge, the physician facing a suit may be able to assist his legal team in optimizing his/her defense.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Michael Menchine, MD, MPH

Submission history: Submitted: September 26, 2009; Accepted: December 29, 2009

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Peter Moffett, MD,Commander MAMC, ATTN MCHJ-EM, Tacoma WA 98431

Email: Peter.moffett@us.army.mil

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

REFERENCES

1. American Medical Association Center for Health Policy Research The Cost of Professional Liability in the 1980’s. Chicago, IL: 1990.

2. Anderson GF. Billions for defense: The pervasive nature of defensive medicine. Arch Intern Med.1999;159:2399–402. [PubMed]

3. The Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts. Available at www.statehealthfacts.org. Accessed May 15, 2009.

4. Restatement of Torts, Second. Section 283.

5. Garthe v. Ruppert, 264 N.Y. 290, 296, 190 N.E. 643.

6. The T.J. Hooper, 60 F:2d 737 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 287 U.S. 662 (1932)

7. Helling v. Carey, 83 Wash. 2d 514, 519 P.2d 981 (1974)

8. Texas & P. Ry. v. Behymer, 189 U.S. 468, 470, 47 L. Ed. 905, 23 S. Ct. 622 (1903)

9. Kelly D, Manguno-Mire G. Commentary: Helling v. Carey, Caveat Medicus. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36:306–9. [PubMed]

10. Revised Code of Washington. Section 4.24.290.

11. Hall v. Hilburn, 466 So. 2d 856 (Miss. 1985).

12. McCourt v Abernathy, 457 S.E.2d 603 (S.C. 1995).

13. Johnston v. St. Francis Medical Center, Inc., No. 3 5, 236-CA, Oct. 31, 2001.

14. Recupero P. Clinical practice guidelines as learned treatises: Understanding their use as evidence in the courtroom. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36:290–301. [PubMed]

15. Napoli A, Jagoda A. Clinical policies: Their history, future, medical legal implications, and growing importance to physicians. J Emerg Med. 2007;33:425–32. [PubMed]

16. Moses R, Feld A. Legal risks of clinical practice guidelines. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:7–11.[PubMed]