| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Eunice Abdul Remane Jethá, MD, MPH | University Eduardo Mondlane, Faculty of Medicine, Maputo Mozambique |

| Catherine A Lynch, MD | Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Atlanta, GA |

| Debra Houry, MD, MPH | Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Atlanta, GA |

| Maria Alexandra Rodrigues, MD, PhD | University Eduardo Mondlane, Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Maputo, Mozambique |

| Christine E. Keyes, MD | Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Atlanta, GA |

| Baltazar Chilundo, MD, PhD | University Eduardo Mondlane, Department of Community Health, Faculty of Medicine, Maputo, Mozambique |

| David W. Wright, MD | Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Atlanta, GA |

| Scott M. Sasser, MD | Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Atlanta, GA |

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

Family violence (FV) is a global health problem that not only impacts the victim, but the family unit, local community and society at large. To quantitatively and qualitatively evaluate the treatment and follow up provided to victims of violence amongst immediate and extended family units who presented to three health centers in Mozambique for care following violence.

Methods:

We conducted a verbally-administered survey to self-disclosed victims of FV who presented to one of three health units, each at a different level of service, in Mozambique for treatment of their injuries. Data were entered into SPSS (SPSS, version 13.0) and analyzed for frequencies. Qualitative short answer data were transcribed during the interview, coded and analyzed prior to translation by the principal investigator.

Results:

One thousand two hundred and six assault victims presented for care during the eight-week study period, of which 216 disclosed the relationship of the assailant, including 92 who were victims of FV. Almost all patients (90%) waited less than one hour to be seen, with most patients (67%) waiting less than 30 minutes. Most patients did not require laboratory or radiographic diagnostics at the primary (70%) and secondary (93%) health facilities, while 44% of patients received a radiograph at the tertiary care center. Among all three hospitals, only 10% were transferred to a higher level of care, 14% were not given any form of follow up or referral information, while 13% required a specialist evaluation. No victims were referred for psychological follow-up or support. Qualitative data revealed that some patients did not disclose violence as the etiology, because they believed the physician was unable to address or treat the violence-related issues and/or had limited time to discuss.

Conclusion:

Healthcare services for treating the physical injuries of victims of FV were timely and rarely required advanced levels of medical care, but there were no psychological services or follow-up referrals for violence victims. The healthcare environment at all three surveyed health centers in Mozambique does not encourage disclosure or self-report of FV. Policies and strategies need to be implemented to encourage patient disclosure of FV and provide more health system-initiated victim resources.

INTRODUCTION

Family violence (FV) is a common problem worldwide that affects people of all socioeconomic backgrounds, educational levels and gender, yet is invisible to most healthcare providers.1,2 FV includes intimate partner violence (IPV), child maltreatment, elder abuse and assault by extended family members. As the family model in Mozambique includes extensive family units (children, parents, in-laws, grandparents, aunts and uncles and cousins), FV in the larger sense can include extended family members as assailants. It not only negatively impacts the victims, but also the victims’ families, including children and adolescents and the community at large.

FV, as defined by this study, is any act or conduct that causes death, injury or physical, sexual or psychological suffering between members of a given household or community united by family ties.3In IPV, over half the time physical abuse is accompanied by psychological abuse and sexual assault.4 IPV and sexual violence can lead to a wide array of long-term physical, mental and sexual health problems, as well as unwanted pregnancy or sexually transmitted diseases including the Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection.5–8 IPV has been associated with higher rates of suicide, drug abuse and alcohol and psychological distress.8 Child maltreatment, in 2002, caused an estimated 31,000 deaths attributed to child homicide among children less than 15-years-old.9Global estimates of child homicide suggest that infants and very young children are at the greatest risk; the 0–4 year age group has a rate more than double those for 5 to 14-year-olds.9 Elder abuse, which can take many forms – including physical, psychological and sexual abuse, financial exploitation, neglect and self-neglect, medication abuse or abandonment – is a topic of growing concern, as the global population of older people is predicted to triple by 2050.10, 11

In different parts of the world, many victims of violence perceive their abuse as a cultural or religious norm that is reinforced by prejudice and discrimination.12 One study found 70% of men and 90% of women believed that beating of a woman to be justified in certain circumstances.13 Many times women cannot seek healthcare without the knowledge or permission of their spouses or male relatives.14 FV victims are often subject to strict controls on their mobility and their ability to seek care. Violence occurs in cycles, repetitively progressing until victims require outpatient and hospital services.15 Despite requiring frequent care, FV is difficult to diagnose as many patients do not routinely disclose violence and may have sequelae from long-term abuse. For many victims of FV, health services constitute the only place to seek support.16 It is common for victims of sexual violence to seek medical assistance, without having made a complaint to the police,17, 18 although many do not seek medical care either. Therefore, healthcare professionals play a key role in detecting and treating FV victims and in preventing further episodes of violence.14 After a victim seeks help from a health institution, his or her reception there is crucial; an indifferent or hostile reaction increases the feeling of isolation, and the victim would be unlikely to bring up the topic again. A lack of confidentiality can be particularly devastating, especially since violence disclosure is rare without direct questioning.

Quality of care is the degree to which the needs, expectations and standards of care of patients have been met. This can be evaluated through efficiency, effectiveness and appropriate supportive relationship between professionals and health system users.19 Actions that threaten the effectiveness of healthcare include: delay to care, inappropriate treatment, intimidation, verbal abuse, threats and perceived non-treatment.20 Difficulty in diagnostics, treatment and follow up can lead victims to be non-compliant with recommendations, thus possibly causing permanent physical and psychological sequelae with concomitant socioeconomic implications that could be avoided or reduced.21

The objective of this study is to quantitatively evaluate the treatments (diagnostic testing, therapies and acute interventions), and follow up provided to patients presenting with FV-related injuries. In addition, we sought to qualitatively evaluate barriers to victim self-disclosure of FV of those who presented to three health centers in Mozambique. In evaluating the care of FV victims, we studied three indicators: time to treatment, diagnostic testing and treatment provided, and the follow up recommended, all of which were reported by patient survey participants. We qualitatively asked these victims about their experience in seeking care at the health facilities.

METHODS

This survey study of a convenience sample was performed during August and September 2007, at three health centers in Mozambique. If a patient self-disclosed as the etiology of an injury, research personnel were informed and approached the possible participant regardless of the victim’s age, sex and type of injury. Study staff were present to enroll patients and collect data at each of the three participating hospital emergency departments 24 hours a day, seven days a week during August and September 2007. The international collaborator’s institutional review board and the local ethics review committee both approved this study prior to data collection.

Setting

Mozambique is located on the southern portion of the eastern coast of Africa. It has over 22 million inhabitants, of whom 48% are male and 37% live in urban areas.22 Portuguese is the national language, yet is spoken by only 27% of the population and often coexists with various tribal languages.22 Mozambique has a young population with 44% under the age of 15, and a life expectancy of 46.7 years.23,24 Maputo, the capitol, is located in Maputo province with approximately two million inhabitants.25 We chose three hospitals representing different levels of capacity within Maputo Province. Hospital Central de Maputo (HCM), a national quaternary referral hospital, Hospital General Jose Macamo (HGJM), a secondary referral center, and the Center for Health Maxaquene (CH), a primary care health center were chosen as a representative sampling of the main three levels of health centers within the city of Maputo.

Preparation

The principal investigator (PI) chose nurses and health workers who worked at each of the three study sites for further training. Each potential interviewer underwent four hours of initial research and interviewing training, had introductory sessions on the survey instrument, and then gained experience with the survey instrument during pilot testing at a separate healthcare facility under the PI’s supervision. We made final improvements to the survey questionnaire and chose final interviewers from those trained, based on interview ability, hospital staffing needs and internal validity on these trial interviews.

Instrument

The two-page survey questionnaire by the PI included multiple choice, yes/no and short answers format questions (available from authors on request). Demographic information, information on the perpetrator and diagnostic and treatment information, including estimate on the time to evaluation, types of treatment required, diagnostics, final diagnoses and follow-up recommendations were collected.

Procedure

Upon identification of a potential participant after self-disclosure of violence to the triage nurse, research personnel approached the victim after medical stabilization to offer participation in the study. The researcher informed the patient of the study protocol and risks and benefits of participation. Each patient signed an informed consent, or verbally assented with guardian consent if the patient was under 18-years-old. The questionnaire was verbally administered in a quiet, secluded and safe location once the patient agreed to participate. Qualitative short answer questions responses were transcribed during the interview then coded and translated. Data was entered into SPSS (SPSS, version 13.0) and analyzed for frequencies and percentages. All data were free of patient identifiers and were kept in a secure location to ensure subject confidentiality.

RESULTS

During the study time period 1,206 individuals presented for treatment of assault at the three study facilities, of whom only 216 disclosed the perpetrator of the violence. Of these 216, 92 (42.6%) were injured by members of the same household, fulfilling inclusion criteria. Most FV victims were women (63%), with primary school or less education (84%), who were students or jobless (69%) and mostly between 15 and 34 years of age (76%), while most reported aggressors were the patient’s spouse (50%) or parent (12%).

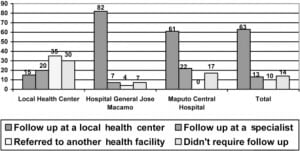

Most patients waited less than 30 minutes (67%) with almost all patients waiting less than one hour (90%). With regard to diagnostic tests, most patients presenting to CH and HGJM did not receive any laboratory or radiograph diagnostics. In contrast, of patients presenting to HCM, 44% received radiographs. In the local Health Center, approximately half of victims did not receive any specific treatment, while at HCM and HGJM only 4% and 17% respectively did not receive any treatment. As displayed in Figure 1, of the total victims of violence involved in this study approximately 14% were not given further referral or follow up. At the local Health Center, 35% were given a referral and 30% were told they didn’t require follow up or referral. In total, almost 10% were transferred to a higher level of care, and 13% received a specialist evaluation. No patients reported referral for psychological care or follow up.

The qualitative survey questions followed three main themes. First, there was a common patient belief that patient reluctance to self-disclose violence could be due to perceptions of lack of physician or health system capacity to assist.

“I don’t know what changes in my treatment if I were to tell everything about what happened. I got this wound on my arm because my aunt hit me with a belt because I did not set the house… What I need is to be treated quickly to not have to tell my friends that I was beaten. The waiting room here fills quickly and the doctor has no time to hear everyone’s story.”

–A victim at HCM

A second theme surrounded the actual or apparent time pressures in the emergency clinic that limited the ability of the physician to inquire about violence.

“I took a beating from my husband who is out there. We went to the police and now we came here because of this wound in the head. To treat the wound it isn’t necessary to say what happened. …at this hospital you can not waste time with stories of each one… there are people that arrive early in the morning because of malaria, diarrhea and are here in the queue for treatment. My problem is not the wound. I’m tired of being beat. I want the police to help me. I stay with my children to show this man who I am … ”

-A victim at CH

“Many people come to HCM to be rapidly treated by a doctor who is very hurried… However eventually many patients are waiting to be seen, and the doctor can not waste time searching for other diseases than those that the person says he has…. So if the patient does not say he was beaten at home nobody will try to guess anything about it. ”

–A victim at HCM

The third theme surrounds legal issues and concerns that self-reporting would require a police intervention. The patient perception that the only assistance a hospital could have would be to document wounds to provide to the police.

“… Only those who want to solve the problem with the police and need to have need hospital document… I want the one who hit me to apologize…I am not here to solve the problem in the hospital because the doctor has nothing to do with this, [what’s] more I want to make him scared….things can’t be like this every day … well, it’s true that if a person could be certain that he could count on the hospital and not be brought to the station maybe other people can say that they were beaten by their husbands.”

–A victim at HGJM

DISCUSSION

We found that time to treatment for almost all FV patients is less than one hour. Since our data was self-reported by patients, we do not know the accuracy of the reported time, but believe this represents an overall satisfaction with the efficiency of care. In most cases in the primary and secondary hospitals no diagnostic tests were performed. Radiographs and laboratory work was performed most commonly by general physicians who most often saw patients at the tertiary hospital MCH.

Of particular concern, not a single patient from our study, after suffering from FV was referred for psychological counseling, social support, or to police for follow up. Many victims of FV and other forms of violence suffer from not only physical injuries but are at high risk for psychological disorders, such as anxiety, depression, antisocial behavior and suicide attempts, especially in female victims. Respondents in our study, regardless of the location of their treatment, indicated that the healthcare professional did not express concern or support that extended beyond physical damage to psychological impact of their victimization.

Perhaps just as concerning was the unanimous patient belief that due to patient volume, physicians focused on physical injuries and not the causes for these injuries. This perceived or actual time pressure leads to under-reporting of FV that can lead to a perceived uncompassionate interaction, and therefore inappropriate follow up and safety or prevention education.

In one study, female victims of IPV identified health professionals as the least able to help in case of aggression by the partner.21 Yet commonly, patients aren’t aware of treatment, referral and support options. To increase reporting, more than three-quarters of the victims suggested that routine questions about violence be incorporated into in the clinical evaluation.21 There are resources in Mozambique for FV victims, so a missed diagnosis not only perpetuates under-reporting but harms the potential future wellness of victims.

A recent qualitative study in neighboring Tanzania found comparable results when surveying healthcare workers’ ability to care for FV victims. Their qualitative discussions found four themes on treatment of victims (of which the two that addressed the barriers to identifying violence in the clinical realm closely align with our own), along with the frustration of being caught between encouraging disclosure and lack of support and time pressures associated with large workload and few resources.26 While this study and ours were done from opposite sides of the patient-provider perspective, these two themes of barrier to diagnostics and care persist.

In some countries, health professionals may refuse to screen for female victims of sexual violence in an attempt to avoid having to testify in court.14 Moreover, at times existing legislation prevents doctors from seeing women who were raped or beaten without authorization from the courts or police. In Zimbabwe, a woman who has been raped may have to wait three or more days for a government medical official, as the authorized physician, to document cases of sexual violence or other aggression, at which point, evidence of a crime might be gone.14 Policies such as these need to be reexamined, as they cause more harm to the victim and do not benefit the community.

To assist in disclosure and use of support services in Mozambique, this nation has implemented 16 “Women and Children” offices where women can file complaints and obtain services. In conjunction with these facilities, legal assistance agencies have developed, reporting locations where women can request police assistance without their aggressors present.27 While a significant step forward in protecting victims, these centers suffer from the same insufficient resources that plague the care environment.27 Other developing countries should consider adopting similar polices, and all countries need to ensure adequate resources for these services.

Ultimately, our study has found that while the treatment of FV victims is timely, the ability of the health system to adequately identify, provide an environment for disclosure and to provide psychological support and follow up is poor. This data will be used to increase education of both healthcare professionals and the population to increase self-referral, disclosure and direct questioning in order to initiate appropriate care. Further studies delineating types and severities of injuries and the benefits of screening versus self-reporting in this setting are warranted.

LIMITATIONS

Our study was based on patients who self-referred for FV. This might have significantly decreased our overall percentage of patients who suffered violence and excluded those who were too severely injured to self-refer. Further selection bias might be seen if those who are likely to self-report are victims with an extensive history of abuse or who desire assistance in leaving the abusive situation. Given limited resources, strict tape-recording and transcribing of qualitative short-answer questions was not logistically possible. Researchers were trained to transcribe what the victims stated and were available for conference during the coding and data analysis portion.

CONCLUSION

While treatment of injuries sustained during FV occurs in a timely manner at health units in Mozambique, the environment for the self-reporting FVand lack of referral suggest a very limited capacity for the health system to address the needs of these victims. Mozambique and other developing health systems would benefit from policies that increase identification, treatment, services and prevention of family violence.

Footnotes

Funding for this project was provided by Fogarty International Center GRant D43:TW007262- and supplement D43:TW007262-S01.

Supervising Section Editor: Abigail Hankin, MD, MPH

Submission history: Submitted January 20, 2011; Revision received March 1, 2011; Accepted March 11, 2011.

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem.

Address for Correspondence: Catherine A. Lynch, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine, 531 Asbury Circle Suite N340, Atlanta, GA 30322

Email: calynch@emory.edu.

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Saffioty H. Violência de género: entre o público e o privado. Presença da Mulher. 1997;31:23–30.

2. Santos A. Violência Doméstica e Saúde da Mulher Negra. Revista Toques. 2001;4(16)

3. UNICEF Domestic violence against women and girls. Innocenti Digest. 2000;6

4. Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottemoeller M. Ending violence against women. Population Reports.1999;27(4):1–43.

5. Heilse L, Garcia-Moreno C. Violence by intimate partners. In: Krug EG, editor. World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. pp. 87–121.

6. Jewkes R, Sen P, Garcia-Moreno C. Sexual Violence. In: Krug EG, editor. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. pp. 149–181.

7. World Health Orgainization, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: taking action and generating evidence.

8. McCauley J, Kolodner K, Dill L, Schroeder A, DeChant H, et al. The “Battering Syndrome”: prevalence and clinical characteristics of domestic violence in primary care internal medicine practices. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:737–46. [PubMed]

9. World Health Orgainization Preventing child maltreatment: a guide to taking action and generating evidence. WHO. 2006.

10. Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, editors. World report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

11. United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs Population Division World population prospects: the 2004 revision. New York: United Nations; 2002.

12. llika A. Women’s perception of partner violence in rural Igbo community. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2005;9(3):77–88. [PubMed]

13. Koenig MA, Lutalo T, Zhao F, et al. Domestic violence in rural Uganda: evidence form a commmunity-based study. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(1)

14. USAID Population Reports, Center for Communication Programs. Rio de Janeiro. 2000;16

15. Snugg N, Inui T. Primary care physician’s response to domestic violence. JAMA.1992;267:3157–3160. [PubMed]

16. Warshaw C. Integrating Routine Inquiry about Domestic Violence into Daily Practice. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:619–20. [PubMed]

17. Munhequete E. Análise da Situação dos serviços Médicos Legais e Sanitários para a Assistência Ás Vítimas de Violência Sexual em Moçambique. Maputo, Mozambique: 2005.

18. Jetha E, Lynch C, Houry D, et al. Family Violence in Maputo, Mozambique. Maputo, Mozambique: 2010.

19. Hortale V, Bittencourt R. Revista Ciência & Saúde Colectiva da Associação Brasileira de Pós-Graduação em Saúde Colectiva. Fiocruz, Brasil: Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública; 2006. A qualidade nos serviços de emergência de hospitais públicos e algumas considerações sobre a conjuntura recente no município do Rio de Janeiro.

20. WHO Integrating Poverty and Gender in to Health Programs. 2005. Available at:www.wpro.who.int/NR/rdonlyres/E517AAA7-E80B-4236-92A1.

21. Rodriguez M, Quiroga S, Bauer H. Breaking the silence: Battered women’s perspectives on medical care. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5:153–158. [PubMed]

22. Central Intelligence Agency CIA Worldfact Book: Mozambique. Available atwww.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/mz.html.

23. INE II Recenseamento Geral da População 1997-Resultados definitivos. Maputo, Mozambique: Instututo Nacional de Estatística; 1998.

24. MISAU Ia Moçambique: Inquérito Demográfico e de Saúde 2003. Maputo, Mozambique: Instituto Nacional de Estatística, Ministério da Saúde; 2004.

25. INE. Instituto Nacional de Estatistica Moçambique 2007.

26. Laisser RM, Lugina HI, Lindmark G, Nystrom L, Emmelin M. Striving to Make a Difference: Health Care Worder Experiences With Intimate Partner Violence Clients in Tanzania. Health Care for Women International. 2009;30:64–78. [PubMed]

27. Osório C. WLSA Moçambique. Vol. 7. Maputo, Mozambique: 2004. Algumas reflexões sobre o funcionamento dos Gabinetes de Atendimento da Mulher e da criança.