| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Andreia B. Alexander, MD, PhD, MPH | Indiana University School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana |

| Kimberly Chernoby, MD, JD, MA | Indiana University School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana |

| Nathan VanderVinne, DO | Indiana University School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana |

| Yancy Doos, | Indiana University-Purdue University, School of Science, Indianapolis, Indiana |

| Navneet Kaur, | Indiana University-Purdue University, School of Science, Indianapolis, Indiana |

| Caitlin Bernard, MD | Indiana University School of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Indianapolis, Indiana |

| Jeffrey A. Kline, MD | Indiana University School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana |

Background

Methods

Results

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

ABSTRACT

Introduction

Unintended pregnancy disproportionately affects marginalized populations and has significant negative health and financial impacts on women, their families, and society. The emergency department (ED) is a promising alternative setting to increase access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services including contraception, especially among marginalized populations. The primary objective of this study was to determine the extent to which adult women of childbearing age who present to the ED would be receptive to receiving contraception and/or information about contraception in the ED. As a secondary objective, we sought to identify the barriers faced in attempting to obtain SRH care in the past.

Methods

We conducted a quantitative, cross-sectional, assisted, in-person survey of women aged 18–50 in the ED setting at two large, urban, academic EDs between June 2018–September 2019. The survey was approved by the institutional review board. Survey items included demographics, interest in contraception initiation and/or receiving information about contraception in the ED, desire to conceive, prior SRH care utilization, and barriers to SRH.

Results

A total of 505 patients participated in the survey. Participants were predominantly single and Black, with a mean age of 31 years, and reporting not wanting to become pregnant in the next year. Of those participants, 55.2% (n = 279) stated they would be interested in receiving information about birth control AND receiving birth control in the ED if it were available. Of those who reported the ability to get pregnant, and not desiring pregnancy in the next year (n = 279, 55.2%), 32.6% were not currently using anything to prevent pregnancy (n = 91). Only 10.5% of participants stated they had experienced barriers to SRH care in the past (n = 53). Participants who experienced barriers to SRH reported higher interest in receiving information and birth control in the ED (74%, n = 39) compared to those who had not experienced barriers (53%, n = 240); (P = 0.004, 95% confidence interval, 1.30–4.66).

Conclusion

The majority of women of childbearing age indicated the desire to access contraception services in the ED setting. This finding suggests favorable patient acceptability for an implementation study of contraception services in emergency care.

BACKGROUND

Despite the decline in unintended pregnancy rates in the United States over the past decade, unintended pregnancy remains a significant public health issue.1 According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), factors for increased risk of unintended pregnancy include the following: age 18–24 years; non-Hispanic Black; low income (<100% federal poverty level); less than high school education; and cohabitation without marriage.2,3 Additionally, unintended pregnancy has significant negative health and financial impacts on women, their families, and society.4-8

The decrease in unintended pregnancy rates in the US has been attributed to increased access and utilization of contraception.2 This decrease can largely be attributed to the contraception benefit of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which required insurance companies to cover contraception without a copay.9 After implementation of the ACA we saw significant increases in contraception utilization and decreases in pregnancy rates, particularly in patients at highest risk for unintended pregnancy.10 However, with nearly three million unintended pregnancies per year,11 the US ranks significantly higher than many other developed countries.12 Thus, there is still significant room for improvement.

The emergency department (ED) is a promising alternative setting to increase access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services including contraception, especially among marginalized populations.13-18 Emerging evidence has suggested it is feasible to provide SRH services in the ED.19

A mandatory aspect of translating medical services from theory into practice (so-called implementation science, or T2 to T3 translation) requires input from patients. Given the dearth of literature on the role of SRH interventions in the ED setting, we conducted a cross-sectional survey to assess patients’ receptiveness to accepting contraception services in the ED. Survey studies are useful when trying to understand respondents’ opinions,20 such as in acceptability studies. The primary objective of this study was to determine the extent to which adult women of childbearing age who present to the ED would be receptive to receiving contraception and/or information about contraception in the ED. As a secondary objective, we sought to identify the barriers faced in attempting to obtain SRH care in the past.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a quantitative, cross-sectional, assisted, in-person survey of women aged 18–50 in the ED setting. This study was approved by the institutional review board at our institution.

Participant Recruitment and Data Collection

A convenience sample of participants were recruited from two large, urban, academic EDs between June 2018–September 2019. Each ED has approximately 100,000 annual visits and serves primarily adult patients. (About 85% of visits at each site are by patients at least 18 years of age.) Eligible participants were women aged 18–50 who presented to the ED for any complaint when a research assistant (RA) was present in the ED. The RAs were volunteers and did not have a set schedule. While it was feasible to collect data 24 hours per day/seven days per week, the RAs dictated their own schedules. We excluded participants from the study if they were intoxicated, exhibiting hostile behavior, non-English speaking, or had a chief complaint of sexual assault (due to the potential introduction of psychological risk). Participants were approached and asked to participate in the study by a RA, after the RA confirmed appropriate timing with the treating emergency physician or resident. If they agreed, participants were given a study information sheet, questions were answered, and verbal consent was obtained. The RAs then verbally administered the survey to participants, capturing their responses electronically. The survey took approximately 10 minutes to complete. No compensation was provided for participation.

Population Health Research Capsule

What do we already know about this issue?

Unintended pregnancy disproportionately affects marginalized populations and has significant negative health and financial impacts.

What was the research question?

Our goal was to determine whether women presenting to the emergency department (ED) would be receptive to contraceptive services in the ED.

What was the major finding of the study?

Most women were interested in accessing contraception in the ED setting.

How does this improve population health?

Increasing access to contraception in the ED for patients at higher risk for unintended pregnancy could help decrease this health inequity.

Survey Development

Survey items were developed by an EM resident (NV). To establish face and content validity, a multidisciplinary team of content experts from emergency medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, and pediatric-adolescent medicine, evaluated the initial survey items. Sequential changes were made to the instrument based on their discussions. Once the survey design was complete, the survey was pilot-tested on five lay family members of EM residents using a cognitive interviewing technique21 to identify issues with timing, wording, and skip patterns. We used feedback from these sessions to revise the survey. Once approved by the research team, the survey was ready for dissemination. The survey was transferred to an electronic data capture system (REDCap, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN); the complete survey is provided in the supplemental appendix.

Measures

Demographics

Demographic questions included race, ethnicity, education, employment status, student status, and relationship status.

Acceptability

Acceptability of receiving contraception and/or information about contraception in the ED was measured by a single, multiple-choice question, “Would you be interested in receiving information about birth control or getting birth control in the ED if it was available?” Participants were given five choices: 1) yes, receive birth control and information; 2) yes, receive information only; 3) no; 4) unsure; and 5) other. To get a better understanding of the context of the participants’ answers we asked additional questions around the participants’ current desire/ability to become pregnant and current contraceptive choices. Examples of these questions include the following: “Would you like to become pregnant in the next year?” with the options of 1) yes, 2) no, and 3) unsure; and “Are you currently using anything to prevent pregnancy?” with the options of 1) intrauterine device (IUD), 2) contraceptive implant, 3) injectable birth control, 4) birth control pills, 5) patch, 6) vaginal ring, 7) condoms, 8) withdrawal, 9) natural family planning, 10) abstinence, and 11) other.

Sexual and reproductive health care

Where participants sought SRH care was determined by a single, multiple-choice question, “Where do you currently seek care for things like birth control, STIs, pap smears, or other GYN health issues?” Participants were given nine response items, with the option to choose more than one item: primary care physician; gynecologist; each ED used in this study listed separately; other ED, Planned Parenthood; institution-affiliated outpatient clinic; other outpatient clinic; and nowhere.

Barriers

We assessed barriers with two multiple-choice questions; the first question was “Have you had any difficulty getting care for things like birth control, STIs, pap smears, or other GYN health issues?” Participants were given yes/no response options. This question was followed up with, “What difficulties have you had?” Participants were given seven options, with the choice to select more than one option: difficulty finding a clinic; difficulty making an appointment; difficulty getting to an appointment; difficulty affording the visit; difficulty affording birth control, medications, etc; receiving criticism or judgment from clinic/staff/doctors/etc; and other.

Sample size and data analysis

A target sample size of 500 participants was determined to represent our ED population with a 95% confidence interval and 5% margin of error. We analyed data with SPSS Statistics 26 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) using descriptive statistics and chi-squared analyses. Due to the nature of our data collection methods, there was <1% missing data.

RESULTS

A total of 505 patients participated in the survey. Participants were predominantly single (n = 276; 54.7%) and Black (n = 240; 47.5%) with a mean age of 31 years (Table). Most (n = 471, 93%) of our participants were sexually active and the majority (n =2 79, 55.2%) also reported not wanting to become pregnant in the next year. Only 7.2% (n = 36) of participants reported primarily using the ED for SRH care needs, with an additional 12.3% (n = 62) of participants stating they did not go anywhere to seek SRH care.

TableDemographics of female patients who participated in a survey regarding access to sexual and reproductive healthcare.

| Demographics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | Range | Mean |

|

|

|

|

| 18–55 | 30.7 | |

| Race | n | % |

|

|

|

|

| Black | 240 | 47.5 |

| White | 204 | 40.4 |

| Other | 40 | 7.9 |

| More than one race | 9 | 1.8 |

| Asian | 3 | 0.6 |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 2 | 0.4 |

| Missing | 7 | 1.4 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 425 | 84.2 |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 56 | 11.1 |

| Missing | 24 | 4.8 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Some high school | 79 | 15.6 |

| High school/GED | 230 | 45.5 |

| Some college | 113 | 22.4 |

| College | 51 | 10.1 |

| Advanced degree | 18 | 3.6 |

| Trade school | 13 | 2.6 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.2 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single | 276 | 54.7 |

| Married | 97 | 19.2 |

| Partnered | 75 | 14.9 |

| Cohabitating | 23 | 4.6 |

| Separated | 17 | 3.4 |

| Divorced | 16 | 3.2 |

| Widowed | 1 | 0.2 |

| Desire for pregnancy in the next year | ||

| Yes | 71 | 24.4 |

| No | 279 | 55.2 |

| Can’t get pregnant | 123 | 24.4 |

| Unsure | 32 | 6.3 |

| Site of usual SRH care | ||

| Primary care physician | 200 | 39.6 |

| Outpatient clinic | 116 | 23 |

| Gynecologist | 101 | 20 |

| Nowhere | 62 | 12.3 |

| Emergency department | 36 | 7.2 |

| Planned parenthood | 28 | 5.5 |

| Interest in contraception in the ED | ||

| Information and contraception | 279 | 55.2 |

| No information or contraception | 187 | 37 |

| Information only | 37 | 7.3 |

| Unsure | 2 | 0.4 |

GED, General Education Development

SRH, sexual and reproductive health; ED, emergency department.

Overall, 55.2% of participants (n = 279) stated they would be interested in receiving information about birth control AND receiving birth control in the ED if it were available. Another 7.3% (n = 37) reported wanting information only.

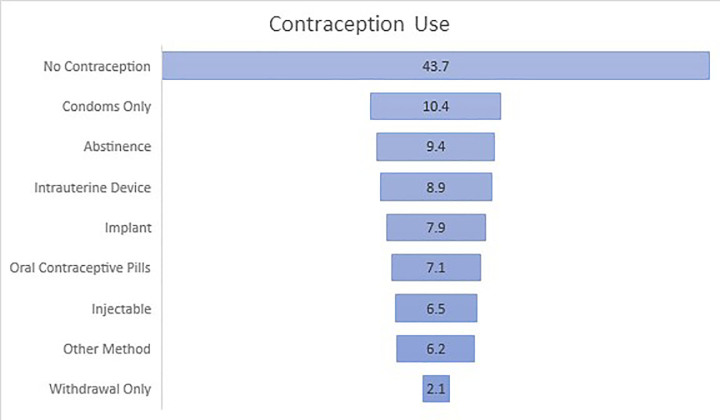

Of participants who self-reported having the ability to get pregnant (n = 382, 75.6%), 56.3% (n = 215) were currently using contraception. Participants were most likely to report using only condoms (n = 40; 10.4%), followed by abstinence (n = 36, 9.4%). Only 23.3% (n = 89) were using a form of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC): IUD (n = 34, 8.9%); implant (n = 30, 7.9%); or injectable (n = 25, 6.5%). The Figure reports a complete account of contraceptive use in participants with the ability to get pregnant.

Of the participants who reported the ability to get pregnant, and also not desiring pregnancy in the next year (n = 279, 55.2%), 32.6% were not using anything to prevent pregnancy at the time of the survey (n = 91). Furthermore, an additional 20.4% (n = 57) were using only condoms and 6.1% (n = 17) were using only the withdrawal method to prevent pregnancy. Similar to the overall sample, 56.6% of these participants stated they would be interested in receiving information about birth control and starting or changing their contraceptive method in the ED if it were available (n = 158).

When asked about barriers to obtaining SRH care, only 10.5% of participants stated they had experienced barriers to care (n = 53). The most common stated barriers to SRH were the following (in descending order): affording birth control (n = 22; 41.5%); affording the visit (n = 17; 32.1%); difficulty making an appointment (n = 16; 30.2%); finding a clinic (n = 15; 28.3%); getting to the appointment (n = 15; 28.3%); and receiving criticism or judgment from the staff/doctors (n = 8; 15.1%). Of the participants who experienced barriers to SRH care, 73.6% reported interest in receiving information about birth control and receiving birth control in the ED if it were available (n = 39). Participants who experienced barriers to SRH services reported higher interest in receiving information and birth control in the ED (74%, n = 39) compared to those who had not experienced barriers (53%, n = 240); (P = 0.004, 95% confidence interval, 1.30–4.66).

In a post hoc fashion we compared interest in ED contraception initiation between participants who were high risk for unintended pregnancy according to the CDC definition3 to those who were not in a high-risk group. We found increased rates of acceptability in participants who were 18–24 years of age (n = 95, 68.9%) compared to >24 years of age (n = 221, 60.2%), non-Hispanic Black (n = 153, 63.7%) compared to non-Hispanic White (n = 146, 54.9%), cohabitating but never married (n = 17, 73.9%) compared to any other relationship status (n = 264, 54.8%), and did not complete high school (n = 46, 58.3%) compared to high school diploma/General Education Development or above (n = 237, 55.6%). None of these factors reached statistical significance at a level of P = 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Among the many factors that determine the feasibility of a study, two important elements are that the intervention is both needed and wanted (acceptable) by the target population.22 In this survey study of women presenting to the ED, most (55.2%) of our participants wanted to receive contraception and information about contraception in the ED and an additional 7.3% wanted information only. To our knowledge, there has only been one study, published in 2005, examining the acceptability of the provision of contraception in the adult ED population.23 In this study, contraception provision in the ED was acceptable to 44% of ED patients. Our rate of acceptability was somewhat higher at 55.2%. This may be secondary to the increase in awareness of and access to contraception over the last decade,24 specifically since the introduction of the ACA contraception benefit.9,10

Todd et al found that acceptability was significantly higher in patients who were uninsured, without a primary care provider, were frequent ED utilizers, and were at increased risk of pregnancy.23 In participants who were at increased risk of pregnancy,3 we found increased rates of acceptability in most categories including those who were 18–24 years of age, non-Hispanic Black, cohabitating but never married, and had not completed high school. We did not collect income information; therefore, we could not compare low to higher income participants. None of these factors reached statistical significance at a level of P = 0.05; however, this study was not powered to answer this question. Additionally, patients who experienced barriers to SRH care reported higher interest in receiving information and birth control in the ED compared to those who did not experience these barriers.

A qualitative study by Caldwell et al found that 81% participants were accepting of contraception counseling in the ED. These participants felt that the ED provided an opportunity to address women’s unmet contraception needs, contraception was within the scope of ED practice, and the ED was a convenient setting with competent providers who could deliver contraception counseling. However, the participants who were not accepting of contraception counseling felt that contraception is a sensitive topic, and the ED is an inappropriate setting to receive contraception counseling.25 While this study further supports the ED as a setting for contraception services, it highlights the need for patient-centered, targeted approaches to ED-based contraception services. Future research should explore these factors further.

Our data suggest that ED-based contraception was both wanted and needed. Of participants who were able to but did not want to get pregnant in the next year, 32.6% of them were not using any form of contraception, with another 26.5% relying on condoms only or the withdrawal method. To reduce unintended pregnancy in the US we need to increase access to contraception by identifying alternative settings for its provision13,26,27 because the traditional settings are insufficient to meet the needs of the most vulnerable populations. The need identified by this study supports the notion that the ED may be an important setting to reach some of our patients who are at high risk for unintended pregnancy and its complications.

While our study showed that acceptability of contraception was high in the ED patients we sampled, further research needs to be completed. First, a similar multisite study of acceptability should be implemented to increase generalizability of these findings. Additionally, feasibility studies in the areas of insurance coverage, physician knowledge and acceptability, and follow-up structure as well as a pilot study should be conducted to ensure successful implementation of contraception initiation in the ED.

LIMITATIONS

Bias may have been introduced into this study as we used a convenience sample rather than a consecutive or random sample. This was because this was an unfunded study. Data was collected by two volunteer RAs, one undergraduate and one medical student. Therefore, data needed to be collected when they were available. While there were no restrictions on when they could collect data, all but two participants were enrolled between 7 am -11 pm. We do not have data on the day of the week data was collected as we did not keep track of dates in order to preserve anonymity and not collect personal health information. Additionally, although we collected data at two large urban EDs, these EDs were located in the same city, limiting generalizability of the results of this study. Another limitation is that we did not keep track of patients who were approached but refused to participate. Therefore, we could not calculate a response rate, and we could not determine whether there was a difference between participants and non-participants. Finally, although insurance status was identified in a prior study as having a significant correlation with acceptability of contraception in the ED,23 this survey was not designed to assess influence of insurance status on decision-making; one of the reasons for this was our concern about confounding from financial literacy,28 because this was coming from the patient not the chart. We did not have IRB approval to look at the electronic health record. This correlation will be explored in future studies.

CONCLUSION

The majority of women of childbearing age indicated the desire to access contraception services in the ED setting. This finding suggests favorable patient acceptability for an implementation study of contraception in emergency care.

Footnotes

Section Editor: Jacob Manteuffel, MD

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Andreia B. Alexander, MD, PhD, MPH, Indiana University School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Fifth Third Bank Building | Third Floor, 720 Eskenazi Avenue, Indianapolis, IN 46202. Email: abalexan@iu.edu. 5 / 2021; 22:769 – 774

Submission history: Revision received September 1, 2020; Submitted February 22, 2021; Accepted February 16, 2021

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. No author has professional or financial relationships with any companies that are relevant to this study. There are no conflicts of interest or sources of funding to declare.

REFERENCES

1. Healthy People 2020. Reproductive and sexual health. 2020. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/leading-health-indicators/2020-lhi-topics/Reproductive-and-Sexual-Health. Accessed May 15, 2020.

2. Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):843-52.

3. Unintended Pregnancy. 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/unintendedpregnancy/index.htm. Accessed July 3, 2020.

4. Cheng D, Schwarz EB, Douglas E, et al. Unintended pregnancy and associated maternal preconception, prenatal and postpartum behaviors. Contraception. 2009;79(3):194-8.

5. Dott M, Rasmussen SA, Hogue CJ, et al. Association between pregnancy intention and reproductive-health related behaviors before and after pregnancy recognition, National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1997–2002. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(3):373-81.

6. Guterman K. Unintended pregnancy as a predictor of child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;48:160-169.

7. Orr ST, Miller CA, James SA, et al. Unintended pregnancy and preterm birth. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2000;14(4):309-13.

8. Sonfield A, Kost K. Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy-related care: National and state estimates for 2010. 2015. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.700.5575&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed May 5, 2020.

9. Preventive services covered by private health plans under the Affordable Care Act. 2015. Available at: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/fact-sheet/preventive-services-covered-by-private-health-plans/. Accessed October 1, 2020.

10. Dalton VK, Moniz MH, Bailey MJ, et al. Trends in birth rates after elimination of cost sharing for contraception by the patient protection and Affordable Care Act. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2024398.

11. Frost JJ, Sonfield A, Zolna MR, et al. Return on investment: a fuller assessment of the benefits and cost savings of the US publicly funded family planning program. Milbank Q. 2014;92(4):696-749.

12. Singh S, Sedgh G, Hussain R. Unintended pregnancy: worldwide levels, trends, and outcomes. Stud Fam Plann. 2010;41(4):241-50.

13. Alexander AB, Ott MA. A social emergency medicine approach to the implementation of sexual and reproductive health interventions in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26(4):457-9.

14. Morganti KG, Bauhoff S, Blanchard JC, et al. The evolving role of emergency departments in the United States. Rand Health Q. 2013;3(2):3.

15. Coster JE, Turner JK, Bradbury D, et al. Why do people choose emergency and urgent care services? A rapid review utilizing a systematic literature search and narrative synthesis. Acad Emer Med. 2017;24(9):1137-49.

16. Cunningham A, Mautner D, Ku B, et al. Frequent emergency department visitors are frequent primary care visitors and report unmet primary care needs. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23(3):567-73.

17. Greenwood-Ericksen MB, Kocher K. Trends in emergency department use by rural and urban populations in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e191919-e191919.

18. Caldwell MT, Choi H, Levy P, et al. Effective contraception use by usual source of care: an opportunity for prevention. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28:306-12.

19. Miller MK, Chernick LS, Goyal MK, et al. A research agenda for emergency medicine–based adolescent sexual and reproductive health. Acad Emer Med. 2019;26(12):1357-68.

20. Mello MJ, Merchant RC, Clark MA. Surveying emergency medicine. Acad Emer Med. 2013;20(4):409-12.

21. Brace I. How to pilot a questionnaire. Questionnaire Design: How to Plan, Structure and Write Survey Material for Effective Market Research. 2018:276-88.

22. Criteria for the development of health promotion and education programs. Am J Public Health. 1987;77(1):89-92.

23. Todd CS, Plantinga LC, Lichenstein R. Primary care services for an emergency department population: a novel location for contraception. Contraception. 2005;71(1):40-4.

24. Hogben M, Ford J, Becasen JS, et al. A systematic review of sexual health interventions for adults: narrative evidence. J Sex Res. 2015;52(4):444-69.

25. Caldwell MT, Hambrick N, Vallee P, et al. “They’re doing their job”: women’s acceptance of emergency department contraception counseling. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(4):515-26.

26. Improving access to quality care in family planning: medical eligibility criteria for initiating and continuing using use of contraceptive methods. 1996. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/61086/WHO_RHR_00.02.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2020.

27. Practice bulletin No. 200: Early pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(5):e197-207.

28. Hoerl M, Wuppermann A, Barcellos SH, et al. Knowledge as a predictor of insurance coverage under the Affordable Care Act. Med Care. 2017;55(4):428-35.