| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Sheryl M. Strasser, PhD, MPH, MSW, MCHES | Georgia State University, Institute of Public Health, Atlanta, GA |

| Judith Kerr, MPH | Georgia State University, Institute of Public Health, Atlanta, GA |

| Patricia S King, RN | Georgia Department of Human Services, Division of Aging Services, Atlanta, GA |

| Brian Payne, PhD | Georgia State University, Department of Criminal Justice, Atlanta, GA |

| Sarah Beddington, MPH | Georgia State University, Institute of Public Health, Atlanta, GA |

| Danielle Pendrick, BA | Georgia State University, Institute of Public Health, Atlanta, GA |

| Elizabeth Leyda, BA | Georgia State University, Institute of Public Health, Atlanta, GA |

| Frances McCarty, PhD, MED | Georgia State University, Institute of Public Health, Atlanta, GA |

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

The aging population is a rapidly growing demographic. Isolation and limited autonomy render many of the elderly vulnerable to abuse, neglect and exploitation. As the population grows, so does the need for Adult Protective Services (APS). This study was conducted to examine current knowledge of older adult protection laws in Georgia among APS staff and to identify training opportunities to better prepare the APS workforce in case detection and intervention.

Methods:

The Georgia State University Institute of Public Health faculty developed a primary survey in partnership with the Georgia Division of Aging Services’ leadership to identify key training priority issues for APS caseworkers and investigators. A 47-item electronic questionnaire was delivered to all APS employees via work-issued email accounts. We conducted descriptive analyses, t-tests and chi-square analyses to determine APS employees’ baseline knowledge of Georgia’s elder abuse policies, laws and practices, as well as examine associations of age, ethnicity, and educational attainment with knowledge. We used a p-value of 0.05 and 95% confidence intervals to determine statistical significance of analyses performed.

Results:

Ninety-two out of 175 APS staff responded to the survey (53% response rate). The majority of respondents were Caucasian (56%) women (92%). For over half the survey items, paired sample t-tests revealed significant differences between what APS staff reported as known and what APS staff members indicated they needed to know more about in terms of elder abuse and current policies. Chi-square tests revealed that non-Caucasians significantly preferred video conferencing as a training format (44% compared to 18%), [χ2(1) = 7.102, p < .008], whereas Caucasians preferred asynchronous online learning formats (55% compared to 28%) [χ2(1) =5.951, p < .015].

Conclusion:

Results from this study provide the Georgia Division of Aging with insight into specific policy areas that are not well understood by APS staff. Soliciting input from intended trainees allows public health educators to tailor and improve training sessions. Trainee input may result in optimization of policy implementation, which may result in greater injury prevention and protection of older adults vulnerable to abuse, neglect and exploitation.

INTRODUCTION

The aging population in America is a rapidly growing demographic. In 2010, an estimated 40 million Americans, or 13%, were age 65 and older.1 Projections speculate that by year 2050, the aged population will more than double to 88.5 million people or approximately 20% of the population.1This growth can be attributed to the aging of the large “baby-boomer” generation and improvements in medical technology that have contributed to extended average lifespan.2,3 As the elderly population increases, so will the number of people living with chronic illnesses and other risk factors for preventable injury, resulting in a greater need for Adult Protective Services (APS). APS was created through federally mandated policies. They are state-administered agencies that intervene on behalf of abused, neglected and exploited adults.4 To date, APS has already noted an increased reliance on its services. Recent publications by Teaster et al.5 and Park et al.6 found that during a four-year period, there was a 16% increase in the reporting of abuse, neglect and exploitation (ANE) to APS nationally. Complementary to these findings, Jogerst et al.7 found that states with mandatory reporting policies of elder abuse receive significantly more reports to APS than states that do not mandate reporting.

Research continues to advance understanding of the magnitude and nature of ANE in the United States. Elder abuse, in all its forms, affects between two and five million American adults over the age of 65.8–11 The spectrum of ANE has been defined by the National Research Council as “intentional actions that cause harm or create a serious risk of harm (whether or not harm is intended) to a vulnerable elder by a caregiver or other person who stands in a trusting relationship to the elder; or failure of a caregiver to satisfy the elder’s basic needs or protect the elder from harm.”10 The dramatic increase in longevity among Americans demands unwavering vigilance against preventable abuses of this vulnerable segment of the population.

Elder abuse is complex, and therefore professionals from diverse disciplines of study can play a role in its identification and resolution. Professions that may potentially be involved in ANE cases include: policy makers, criminal justice and law enforcement, financial/banking industries, law, social services, dentistry and medicine.12–14 However, the responsibility for recognizing, identifying, and responding to ANE of older adults most commonly falls on healthcare professionals. A recent study involving family practice physicians found that roughly half of the respondents had identified cases of elder abuse within the last year.15 The study also noted that Iowa, the state where the survey was administered, is one of a very few states that requires continuing education on elder abuse reporting for designated reporters as mandated by law. Furthermore, the majority of existing elder abuse screening and assessment tools are designed to be administered by healthcare professionals within clinical settings.16 However, it is plausible to assume that less aggressive abuse may be detectable before it escalates to necessitate medical intervention. The early detection of abuse relies heavily on professionals who typically serve as first responders to calls or complaints of domestic abuse situations, such as law enforcement and APS staff.

A call to APS does not guarantee that ANE cases involving older adults will be opened unless there is sufficient evidence to warrant continued attention. Research reveals that rates of investigation are highly dependent on the infrastructure in place to deal with ANE.17–18 At the state level, higher investigation rates have been associated with a mandatory reporting policy and penalties for failure to report.17 Substantiation-to-investigation ratios are higher in states that have more abuse definitions in policies, regulations, and laws, as well as those that have separate caseworkers for child and elder abuse investigations.17 At the county level, the location of APS and county government resources are related to both rates of investigations and rates of substantiations.18 Unfortunately, it is difficult to determine the percentage of reports that are being investigated. According to a survey study conducted by Jogerst et al.,19 34 of the participating states kept no records on the total number of reports of ANE in light of substantiated cases. The true burden of ANE is likely grossly underreported.

One of the greatest challenges of quantifying the burden of ANE cases are the methods of evaluation used. Jones et al. 20 determined that victim complaints account for less than 30% of ANE reports and that the majority of cases are detected by clinicians during urgent care visits. The complexities of evaluating cases of abuse are often confounded by natural aging processes, such as compromised skin integrity or bruising that may be attributed to medication.21–23 Consequently, in some clinical settings expert abuse teams have been formed to initiate comprehensive assessments in suspicious cases.24 Since even clinicians may miss elder abuse among older adults, professionals on the frontline of initial case reporting must receive adequate training to improve identification of potential ANE.

Studies Calling For Increased Professional Training

Current research in the field of ANE recommends increased professional training in a variety of fields, including medical professionals, policy makers, public health officials, medical examiners/coroners and APS staff.15,20,25–30 The National Adult Protective Service Association, in partnership with the National Center on Elder Abuse, specifically state that comprehensive training for new and experienced APS employees and their supervisors is essential.30 Additionally, the National Institute of Justice, the research, development and evaluation branch of the United States Department of Justice recently published a report emphasizing the multidisciplinary need for training in all professions that can potentially detect cases of ANE, including the APS workforce.31

Theoretical Context of Study

Older adults who experience abuse suffer decreased quality of life and functional status. Dong32found that elderly victims of abuse report poorer functional status and increasing dependency, greater social isolation, poorer health, and increased reports of helplessness and stress, as well as psychological deterioration. Abuse and neglect have also been identified as independent predictors for higher mortality as found in Lachs et al.33 and Dong et al.34. This trend has important implications for public health professionals who can provide enhanced training, education and response systems for all professionals involved in elder abuse cases. APS staff members play an integral role in identifying ANE. They can be trained to enhance their ability to detect indicators of elder abuse, such as emaciation, bruising, broken bones and burns. This can be vital in early intervention for victims and timely prosecution of abusers. APS staff members’ enhanced ability to identify abuse and recognize Georgia ANE laws may lead to greater levels of case substantiation, and subsequently, more accurate insights into the true scope and breadth of the ANE burden throughout the state would be gained. The purpose of this study is to understand APS staff knowledge of ANE policies laws, practices for case substantiation, and preferences for future training so that the prevention of ANE can be maximized.

METHODS

Researchers received the E-mail directory of all 175 APS staff members located throughout the state of Georgia from the state Division of Aging Services. Researchers invited all APS staff members to complete the survey if they provided an indication of consent. Authors developed survey questions based upon a review of the literature and current ANE policies and procedures pertaining to APS operations in Georgia. Senior leadership at the Georgia Division of Aging Services drafted and reviewed survey items so face validity and clarity of the instrument could be ensured. Three non-APS staff members completed a pilot of the survey and provided feedback on the ease of survey administration, time for completion and organization of items. Researchers examined 39 survey items for this descriptive baseline study.

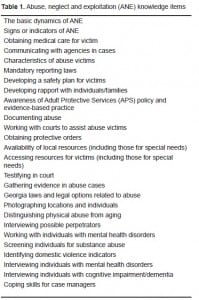

The first section of the survey asked APS staff 26 knowledge-related items. These items were designed to establish a proxy understanding of individual knowledge and content-specific training needs. The survey asked APS staff members to indicate the level of knowledge they think their colleagues currently have about each aspect of ANE and to indicate how much knowledge they think their colleagues need to have about each item in order to be effective in their job. Response options were ‘1-almost none,’ ‘2-a little,’ ‘3-some,’ and ‘4-a lot’ (Table 1).

The next set of survey items focused on training practices and policies at APS. The survey asked, “How would you describe the minimum standards for training currently in place for all APS staff?” Response categories included: no policy/not applicable; staff is encouraged to seek training; some staff required to attend training depending upon the topic; all staff is required to attend training. A follow-up question asked respondents about minimum training standards currently in place for new APS staff. The response options included: there is formal on-the-job training, but no instructor-led training; there is informal training provided by my supervisor or a peer; there is instructor-led training; or I am not aware of new staff training policies. The next item asked how frequent required training should be offered. Options included quarterly, annually, as needed or a free response option.

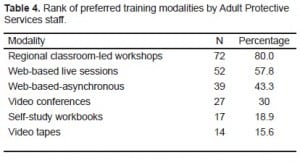

The final section of the questionnaire gathered demographic information as well as preferred training methods. The survey asked participants to identify their race, age, gender, number of years working with APS, urbanicity of practice area, as well as preferred methods of training. Respondents could select multiple training methods from the following choices: video conferences, video tapes, web-based-asynchronous, web-based-live, classroom led/instructor lead workshops, self-study workbooks and other with a field for elaboration.

RESULTS

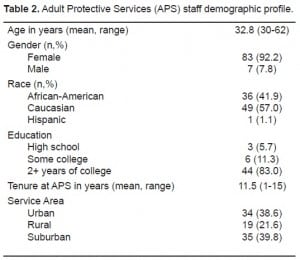

Ninety-two out of 175 APS staff responded to the survey (53% response rate) following three rounds of invitations. An overwhelming majority of participating APS employees were women (92%) with college (50%) or graduate school (30%) education. Over half of APS staff self-identified as Caucasian (56%), followed by African-American (41%). The majority of respondents have worked for APS between one and 15 years (mean 11.5 years of service). The mean age of Georgia APS staff was 32.8 years (SD=10) with ages ranging from 30-years-old to 62-years-old. According to respondents, APS employees deliver services equally in rural (39.8%) and urban (38.6%) areas and less so in suburban areas (21.6%), [Table 2].

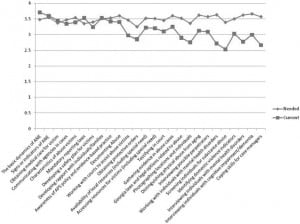

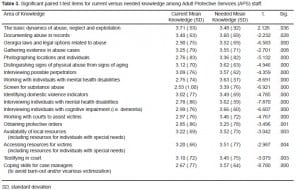

In terms of knowledge possessed and knowledge needed by APS staff, we identified significant differences in 18 out of the 26 items (Figure 1). Items where knowledge needed was statistically different from current knowledge possessed are presented in Table 3.

For the section that asked APS staff to describe the minimum training standards currently in place, 59% of respondents indicated that all staff were required to attend training, 18.5% indicated that some staff were required to attend training depending on the topic, 12% responded that staff was encouraged to seek training, and finally, 11% indicated that no policy existed or it was not applicable. Over half the sample (53%) indicated that the frequency of ANE training should be offered on an as-needed basis. Furthermore, 22% of respondents were not aware of policies for training new APS employees.

This study also sought to discern the preferred method of training as reported by survey participants. Table 4 presents the preferred training modalities in order. We also examined tests of association between preferred training methods and demographic characteristics. Chi-square tests revealed that non-Caucasians significantly preferred video conferencing as a training format (44% compared to 18%), [χ2(1) = 5.900 p ≤ .015], whereas Caucasians preferred asynchronous online learning formats (55% compared to 28%), [χ2(1) = 4.936, p ≤ .026]. We also found significant associations between training preferences and educational attainment. Staff members with graduate level education were more likely than those with four year college education to choose self-study workbooks as a viable training option (34.6% compared to 11.4%), [χ2(1) = 4.165, p ≤ .041]. Staff members with graduate level education were also more likely to choose video conferences (46.2% compared to 18.2%), [χ2 (1) = 4.970, p≤.026] than employees with four year college education.

DISCUSSION

This exploratory study is important because little research has focused on APS staff and their knowledge of elder abuse policies and case investigation procedures. There is a critical window of opportunity for APS staff in terms of early detection, intervention and potential prevention of further elder victimization. This study highlights specific educational topics and training insights for public health professionals and researchers to consider. The impact of premature death, violence and suffering at the end of life is an urgent matter that warrants increased focus and attention. Including APS staff in future scientific inquiry, research and training is paramount to advancing the ANE agenda.

Knowledge of ANE policies and case investigations may be associated with other demographic factors, such as age, gender and race. These patterns were not examined in this initial study. In further research, analysis of the diversity of the sample and the role of education (80% of sample had a college education and higher) in a regression model would be worthwhile to further reveal potential avenues for more appropriately staged training development.

Of the 18 statistically-significant paired samples t-tests between the perceived levels of knowledge attained and needed only one measure, the basic dynamics of ANE, showed that the APS staff members’ current knowledge (M = 3.71, SD = .53) exceed needed knowledge (M = 3.4831, SD = .92) [t(88) = 2.13, p< 0.05 (two tailed)]. For the remaining 17 knowledge areas, APS staff members knew significantly less than what was needed pertaining to service delivery. These 17 significant items can be condensed into four more general categories.

APS staff indicated the greatest knowledge needs are in areas of evidence collection, legal procedures, cross training and serving clients with mental health disabilities. Each of these four categories contains at least two items reported as areas of needed knowledge. The need for knowledge on the collection of evidence and relevant legal procedures are closely aligned. The more clearly and concretely APS staff can prove abuse, the more effectively the legal system can uphold policies in place to protect vulnerable adults. Gaps or mistakes in evidence collection may slow and even undermine advocacy of elderly individuals within the court system. Since most courts have limited resources and deal with a wide variety of cases, improvements in specialized legal knowledge could draw greater judicial attention and resources to elder abuse.

Likewise, deficiencies in knowledge regarding cognitive impairment and cross training underline the unique vulnerabilities of the population served by APS agencies. Elderly people suffer illness and injury in ways unlike individuals in younger life stages. If APS staff members recognize this problem, yet are unable to fully address it, this may impact APS staff members’ job satisfaction and the ability to fulfill their role in cases where vulnerable individuals are being victimized.

These results substantiate previous research that calls for increased education and professional training in all fields that may be able to identify EM.25,27,35 In a study by Lindbloom et al35substantial knowledge deficit in the field of ANE case investigation was revealed. They found that the majority of APS staff did not know how to distinguish evidence of physical abuse and neglect from the normal course of chronic disease and physical decline. This is a critical skill in ANE case identification.35 Similarly, in our study, APS staff felt they needed significantly more training in the area of distinguishing abuse from signs of aging compared to what they perceive themselves as currently knowing.

In consideration of the minimum training standards questions, the reality is that no standardized mandatory training is specified within the Georgia standard operating policies for the APS workforce. Only 11% of the sample correctly acknowledged this. The Division of Aging Services leadership has acknowledged the need to specify a mandated training policy which would delineate minimum requirements by type and frequency of training for the APS workforce. This is currently being negotiated but has yet to be implemented.

The final results specify training preferences among the APS staff sample. Eighty percent preferred classroom or instructor-led ANE training sessions. However, web-based modalities were the next highest favored, with web-based live training selected by 52 respondents (58%), followed by web-based asynchronous training (43%). These preferences are helpful to those planning further ANE education and training. Combined with the results of the t-tests, these survey findings reveal specific opportunities for enhancing training aimed at APS staff who play a critical role in identifying and addressing elder abuse.

LIMITATIONS

This study was based on a small and homogenous sample. It is also limited by the voluntary nature of the survey. The answers provided by the respondents may not be indicative of the non-respondents. It also would have been helpful for training development to understand the ways that APS staff came to possess the domains of knowledge that were assessed in this survey. Additionally, policies, regulations, responsibilities, and qualifications of APS are determined by individual states and/or local municipalities. Due to the varied range of APS requirements and roles across the county, the generalizability of these study results is limited to locales that follow Georgia’s APS structure and scope of work.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates an awareness of differences not yet adequately addressed by educational methods currently available to APS staff members. Low levels of training for the prevention of elder abuse are failing to meet high levels of need. The result is that many older adults are at unacceptable risk for subjection to violence and injury. Enhancements to the way APS staff are trained can begin to narrow the gap, which could translate into improved standards of living and prevention of abuse for many vulnerable elderly adults. Survey responses indicate that effective training for APS employees is the linchpin of effective delivery of services. Without appropriate training, the overarching purpose of APS is compromised. Empowering those who serve the elderly is critical to ensuring the health, wellbeing, and safety of millions of older Americans.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Abigail Hankin, MD, MPH

Submission history: Submitted: January 18, 2011; Revision received February 25, 2011; Accepted March 3, 2011.

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem.

Address for Correspondence: Sheryl M. Strasser

Georgia State University, Institute of Public Health, Urban Life Building, 140 Decatur St., Atlanta, GA 30303

Email : sstrasser@gsu.edu.

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Vincent GK, Velkoff V. The next four decades: the older population in the United States: 2010 to 2050 (Current Population Reports No P25-1138) Washington, DC: U. S. Census Bureau; Available at:http://www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p25-1138.pdf. Accessed October 20, 2010.

2. Daichman LS, Aguas S, Spencer C. Elder Abuse. In: Heggenhougen Kris, Quah Stella., editors.International Encyclopedia of Public Health. Vol. 2. San Diego: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 310–5.

3. Dauenhauer JA, Mayer KC, Mason A. Evaluation of adult protective services: perspectives of community professionals. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2007;19:41–57. [PubMed]

4. Teaster PB, Wangmo T, Anetzberger G. A glass half full: the dubious history of elder abuse policy. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2010;22:6–15. [PubMed]

5. Teaster PB, Dugar DA, Tyler A, et al. The 2004 survey of State Adult Protective Services: abuse of adults 60 years of age and older. The National Committee for the Prevention of Elder Abuse and The National Adult Protective Services Association, prepared for The National Center on Elder Abuse by the Graduate Center for Gerontology, University of Kentucky. Available at:http://www.ncea.aoa.gov/ncearoot/main_site/pdf/21406%20final%2060+report.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2010.

6. Park K, Johnson K, Flasch S, et al. Structuring decisions in adult protective services. Available at:http://www.nccdcrc.org/nccd/dnld/Home/Structuring_Decisions_in_Adult_Protective_Services.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2010.

7. Jogerst JG, Daly JM, Brinig MF, et al. Domestic elder abuse and the law. Am J Public Health.2003;93:2131–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

8. Pillemer K, Finkelhor D. The prevalence of elder abuse: a random sample survey. Gerontologist.1988;28:51–7. [PubMed]

9. Podnieks E. National survey on abuse of the elderly in Canada. J Elder Abuse Negl. 1992;4:5–58.

10. National Research Council. Elder mistreatment: Abuse, neglect, and exploitation in an aging America Panel to review risk and prevalence of elder abuse and neglect. In: Bonnie RJ, Wallace RB, editors. Committee on National Statistics and Committee on Law and Justice, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003.

11. Laumann EO, Leitsch SA, Waite LJ. Elder mistreatment in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a nationally representative study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008;63:S248–54.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

12. Choi NG, Mayer J. Elder abuse, neglect, and exploitation. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2000;33:5–25.[PubMed]

13. Lachs MS, Pillemer K. Elder abuse. Lancet. 2004;364:1263–72. [PubMed]

14. Payne BK. Crime and elder abuse: an integrated perspective. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 2005.

15. Oswald RA, Jogerst GJ, Daly JM, et al. Iowa family physician’s reporting of elder abuse. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2005;16:75–88.

16. Fulmer T, Guadagno L, Bitondo C, et al. Progress in elder abuse screening and instruments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:297–304. [PubMed]

17. Jogerst G, Daly JM, Brinig M, et al. Domestic elder abuse and the law. Am J Public Health.2003;93:2131–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

18. Jogerst GJ, Daly JM. County government resources associated with dependent-adult abuse investigations in Iowa. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2008;20:251–64. [PubMed]

19. Jogerst G, Daly JM, Dawson JD, et al. APS investigative systems associated with county reported domestic elder abuse. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2005;16:1–17. [PubMed]

20. Jones J, Dougherty JD, Schelbie D, et al. Emergency department protocol for the diagnosis and evaluation of geriatric abuse. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;17:1006–15. [PubMed]

21. Mosqueda L, Burnight K, Solomon L. The life cycle of bruises in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc.2005;53:1339–43. [PubMed]

22. Muehlbauer M, Crane PA. Elder abuse and neglect. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv.2006;44:43–8. [PubMed]

23. Strasser SM, Fulmer T. The clinical presentation of elder neglect: what we know and what we can do. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2007;12:340–9.

24. Fulmer T, Paveza G, VandeWeerd C, et al. Dyadic vulnerability and risk profiling for elder neglect.Gerontologist. 2005;45:525–34. [PubMed]

25. Yaffe MJ, Wolfson C, Lithwick M. Professions show different enquiry strategies for elder abuse detection: implications for training and interprofessional care. J Interprof Care. 2009;23:646–54.[PubMed]

26. Dunlop BD, Rothman MD, Condon KM, et al. Elder abuse: risk factors and use of case data to improve policy and practice. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2001;12:95–122.

27. Ingram EM. Expert panel recommendation on elder mistreatment using a public health framework. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2004;15:45–65.

28. Lindbloom E, Kruse R, Brandt J, et al. Mandatory reporting of nursing home deaths: markers for mistreatment, effect on care quality, and generalizability. US Department of Justice. 2008

29. Payne BK. Training adult protective services workers about domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2008;14:1199–213. [PubMed]

30. National Adult Protective Services Association (NAPSA) Adult protective services core competencies. Available at: www.apsnetwork.org/Resources/docs/CoreCompetencies71005.ppt. Accessed on October 29, 2010.

31. Bulman P. Elder Abuse Emerges From the Shadows of Public Consciousness. National Institute of Justice Journal #265. Available at: http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij/journals/265/elder-abuse.htm. Accessed on February 4, 2011.

32. Dong X. Medical implications of elder abuse and neglect. Clin Geriatr Med. 2005;21:293–313.[PubMed]

33. Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, et al. The mortality of elder abuse. JAMA. 1998;280:428–32.[PubMed]

34. Dong X, Simon M, Mendes de Leon C, et al. Elder self-neglect and abuse and mortality risk in a community-dwelling population. JAMA. 2009;302:517–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

35. Lindbloom E, Brandt J, Hawes C, et al. The role of forensic science in identification of mistreatment deaths in long-term care facilities: final report. US Department of Justice. 2005