| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Kevin M Swartout, PhD | Department of Psychology, Georgia State University, Atlanta, Georgia |

| Sarah L Cook, PhD | Department of Psychology, Georgia State University, Atlanta, Georgia |

| Jacquelyn W White, PhD | Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, North Carolina |

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

The purposes of this study were to assess the extent to which latent trajectories of female intimate partner violence (IPV) victimization exist; and, if so, use negative childhood experiences to predict trajectory membership.

Methods:

We collected data from 1,575 women at 5 time-points regarding experiences during adolescence and their 4 years of college. We used latent class growth analysis to fit a series of person-centered, longitudinal models ranging from 1 to 5 trajectories. Once the best-fitting model was selected, we used negative childhood experience variables—sexual abuse, physical abuse, and witnessing domestic violence—to predict most-likely trajectory membership via multinomial logistic regression.

Results:

A 5-trajectory model best fit the data both statistically and in terms of interpretability. The trajectories across time were interpreted as low or no IPV, low to moderate IPV, moderate to low IPV, high to moderate IPV, and high and increasing IPV, respectively. Negative childhood experiences differentiated trajectory membership, somewhat, with childhood sexual abuse as a consistent predictor of membership in elevated IPV trajectories.

Conclusion:

Our analyses show how IPV risk changes over time and in different ways. These differential patterns of IPV suggest the need for prevention strategies tailored for women that consider victimization experiences in childhood and early adulthood.

INTRODUCTION

Latent Trajectories of Intimate Partner Violence Victimization

Male physical violence against women within the context of an intimate relationship—intimate partner violence (IPV)—is an unfortunate global reality. Over 30% of women in the United States (U.S.) are physically victimized by their intimate partners at some point during their lives.1 Although similar rates have been found for men and women, the consequences of male-to-female IPV are decidedly more severe; the majority of patients who visit emergency departments for IPV-related injuries are women,2and far more women are killed at the hands of male partners than the converse.3 This study analyzed longitudinal data on women’s experiences of IPV victimization to test whether there is a single trajectory of IPV across time that represents all women or if there are multiple trajectories.

Because IPV occurs within the context of intimate relationships, it is common for women to be repeatedly victimized: one in three victims of IPV reported experiencing 4 or more incidents of physical violence committed by the same partner.4 In fact, the strongest predictor of IPV victimization is previous victimization.5 Researchers know more about characteristics of perpetrators who commit multiple acts of IPV, than about victims.6,7 Researchers also know a large proportion of IPV victims were also victims of childhood abuse, a phenomenon known as revictimization.8,9 Revictimized women report experiencing significantly more depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder related symptomology than women without a history of victimization.10

The purpose of this investigation is to determine whether latent trajectories of physical IPV victimization exist, and if so, the role of revictimization in these trajectories. We tested a series of latent class growth models to assess meaningful patterns of IPV experiences using longitudinal data collected from female college students. Latent class growth analysis (LCGA) is a simplified case of growth mixture modeling where within-class variances are fixed at zero.11,12 This technique has been used previously to explore trajectories of female sexual victimization.13

Our first research question concerned latent heterogeneity within our sample in terms of the frequency of IPV experiences across time. Based on the previous literature, we expected to find at least 2 distinct subgroups: a large group of women who were not victimized during adolescence or college and a smaller group of women who were consistently victimized across this time period.5

Our second research question examined whether negative childhood experiences could differentiate between groups that emerged. To test this question we explored whether childhood sexual abuse, witnessing domestic violence and parental physical punishment predicted latent trajectory membership. Consistent with previous literature, we hypothesized these negative childhood experiences would differentially predict IPV trajectory membership.

METHODS

Participants

Data for this study are part of a large longitudinal dataset of social experiences (data available at http://dx.doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR03212). Participants were 18- to 19-year-old women enrolled at a medium-sized university in the southeastern U.S. Two incoming classes of first-year women were invited to complete a series of 5 surveys over 4 years of college; 85% of women invited agreed to participate by completing the initial survey (n = 1,575). Approximately 25.3% of women self-identified as African-American, 70.9% as Caucasian, and 3.8% identified with other ethnic groups. Participants’ average age was 18.3 years; 92.8% had never been married.

Procedure

The local institutional review board approved all procedures. The surveys gauged a number of social experiences including predictors, correlates, and consequences of interpersonal violence. Data collection at the first time-point—negative childhood experiences and adolescent IPV victimization—was conducted during the university’s fall first-year orientation for 2 consecutive years with hour-long sessions conducted by trained undergraduate orientation leaders. Leaders acquired informed consent before survey administration after explaining the purpose and method of data collection. Experiences during each year of college—collegiate IPV victimization—were assessed at the end of the spring semester over the subsequent four years. Participants were given $15 in exchange for each survey completed. To protect confidentiality, the third author obtained a federal Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Mental Health. Yearly participant retention rates were 89%, 86%, 80%, and 78%, respectively; 47.2% of the initial sample completed all 5 time-points of the study.

Measures

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV): The Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS)14,15 assessed physical IPV victimization during adolescence and college. The CTS has been the most widely used measure over 3 decades of research on conflict and violence within intimate relationships. Participants are asked to indicate the number of times they have experienced: (1) threats to hit or throw something at the participant; (2) throwing something; (3) pushing, grabbing, or shoving; (4) hitting or attempting to hit, but not with anything; or (5) hitting or attempting to hit with something hard. The item assessing whether a respondent was “beaten up” was excluded due to low endorsement-rates during pilot testing. Participants responded to each item on a scale ranging from 1 to 5, with 1 = “never,” 2 = “once,” 3 = “2 to 5 times,” 4 = “6 to 10 times,” 5 = “more than 10 times.” IPV experiences during high school were assessed at the first time point, and experiences during each year of college were measured during each subsequent time points. Responses were coded so “never” was scored 0, “once” was scored 1, “2 to 5 times” was scored 2, “6 to 10 times” was scored 6, and “more than 10 times” was scored 11.

Negative Childhood Experiences: Participants provided retrospective reports of childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and witnessing domestic violence during initial data collection. Each form of abuse was assessed based on measures used by Koss, Gidycz, and Wisniewski.16

Childhood Sexual Abuse: Childhood sexual abuse was defined as being a victim of sexual acts perpetrated by an adult or any coercive sexual act perpetrated by a similarly-aged peer prior to the age of 14 (e.g., “A person fondled you in a sexual way or touched your sex organs or asked you to touch their sex organs”). Four items were recorded on 5-point scales ranging from “Never had this experience” to “More than 5 times;” the resulting childhood sexual abuse frequency ranged from 0 to 24.

Parental Physical Abuse: Parental physical abuse was defined as recurrent experiences, rather than rare events, during childhood. Participants read the following: “Physical blows (like hitting, kicking, throwing someone down) sometimes occur between family members. For an average month, when you were growing up (i.e., ages 8 to 14 years), indicate how often one of your parents did this to you.” Participants responded on a 5-point scale ranging from “Never” to “Over 20 times.” Responses were recoded to yield a frequency score that ranged from 0 to 21.

Witnessing Domestic Violence: Witnessing domestic violence was defined by the statement: “For an average month, indicate how often one of your parents or stepparents delivered physical blows to the other.” Participants responded on a 5-point scale ranging from “Never” to “Over 20 times.” Responses were recoded to yield a witnessing domestic violence frequency that ranged from 0 to 21.

Analytic Strategy

We conducted an LCGA with Mplus version 5.1 to estimate models using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors.17 Because this estimator assumes data are missing at random, it uses all cases and all data to estimate model parameters.18 Please see White and Smith (2009) for an overview of attrition within this sample.19 The frequency of physical victimization at each time-point was entered as an indicator in the analysis. Thus, the latent trajectory class structure is based on patterns of physical victimization frequency across time. We designated the frequency variables as count, which prompted the software to use a Poisson distribution—where the mean equals the conditional variance.20 To assess the power of past negative childhood experiences in discriminating between latent trajectory classes, we regressed class membership on childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and witnessing domestic violence; although these three variables were not used to estimate the latent groups or classes.

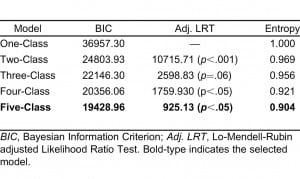

The data were fit to LCGA models ranging from 1 to 5 classes. When building a mixture model there is no singular indicator of model fit; multiple statistical indicators must be paired with a theoretical understanding of the constructs to determine an appropriate class structure.21,22 We used the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted Likelihood Ratio Test to compare model fit, and entropy and posterior probabilities to compare how cleanly each model classified cases into each class structure.23 In addition, we reviewed plots of estimated means for each model to compare heterogeneous class structures with past theoretical and empirical information concerning frequency of sexual victimization. We used negative childhood experience covariates to establish additional discriminant validity between the latent trajectory classes.24

RESULTS

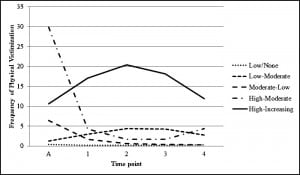

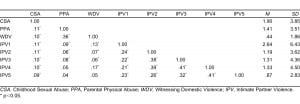

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between variables used in the modeling process are presented in Table 1. The five-class model best fit the data, significantly better than the 4-class model (p= 0.04) according to the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted Likelihood Ratio Test. The 5-class model has a higher BIC compared with the 4-class model; although the entropy is a bit lower for the 5-class model compared with the 4-class model (.904 versus .921), both exhibited respectable classification quality. Finally, we selected the 5-class model because we found it most interpretable; see Figure 1 for the estimated means plot of the 5-class model. We interpreted each of the latent trajectory classes below based on parameters noted in Table 2 and the plot depicted in Figure 1.

Low or No IPV

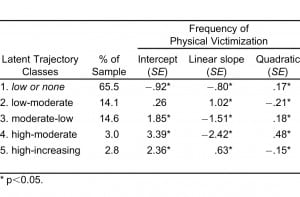

Of the 5 classes, this class had the highest most-likely membership (n=1066, 67.6%). The intercept of this trajectory class is significantly lower than the average frequency at baseline (see Table 3). Although the linear and quadratic slopes are significant, the frequency of IPV in this trajectory starts and stays low across the 5 time-points (Figure 1). Because most-likely members of this class experienced little to no victimization across the study, this class was used as the reference group for the multinomial logistic regressions of latent trajectory class membership on the negative childhood experience variables.

Low to Moderate IPV

This class is estimated to account for over 12% of the sample (n=200). The intercept of this trajectory class is not significantly different from average, but its linear slope is significantly positive and its quadratic slope is significantly negative (Table 3). This translates to a trajectory including women who have slightly elevated levels of victimization during adolescence and then experience more IPV as they progress through college, although this increase is somewhat attenuated during their fourth year of college (Figure 1). We interpreted this latent class as the low to moderate IPV trajectory for these reasons.

Moderate to Low IPV

This class accounted for over an estimated 14% of the sample (n=218). The intercept of this trajectory class is significantly higher than average, the linear slope is significantly negative, and the quadratic slope is significantly positive (see Table 3). Figure 1 and Table 4 show IPV frequency is elevated during adolescence but drops sharply beginning at year 1 of college to a consistently low frequency thereafter. For this reason we interpreted this latent class as the moderate to low IPV trajectory.

High to Moderate IPV

This class is one of the smaller groups in terms of most-likely membership (n=47, 3.0%). In a similar pattern to the moderate to low trajectory, this trajectory has a significantly above average intercept, a significantly negative linear slope, and a significantly positive quadratic slope. The obvious difference between these two trajectories—as depicted in Figure 1—is the intercept of this trajectory greatly exceeds that of the moderate-to-low IPV trajectory. Women in this IPV trajectory are the most highly victimized group during adolescence, but these levels drop sharply at year 1 of college, although a moderate level of victimization persists across college. We interpreted this latent class as the high to moderate IPV trajectory.

High to Increasing IPV

The final class is the smallest group in terms of most likely membership (n=44, 2.8%). The intercept of this class trajectory is significantly higher than the average, the linear slope is significantly positive, but the quadratic slope is significantly negative (Table 3). This translates to a trajectory of women who are highly victimized during adolescence and whose average frequency of victimization experiences actually increase in number after they enter college, although this increase is somewhat attenuated toward their later 2 years of college (Figure 1). These factors let us to interpret this latent class as the high to increasing IPV trajectory.

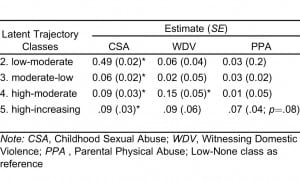

Negative Childhood Experiences

We specified observed negative childhood experience variables as auxiliary covariates to predict latent trajectory class membership. With the low or no trajectory class as the reference group, multinomial logistic regressions suggested that negative childhood experiences predicted IPV victimization trajectory membership (Table 3). Childhood sexual abuse predicted membership in all of the elevated IPV victimization trajectories when compared with the low or no victimization trajectory. Furthermore, witnessing domestic violence predicted membership in the high to moderate trajectory, and parental physical abuse marginally predicted high to increasing trajectory membership.

DISCUSSION

Our primary goal was to investigate the heterogeneity of women’s experiences of IPV beginning in adolescence and spanning their 4 years of college. Using a person-centered approach to longitudinal data analysis, we identified 5 clearly articulated trajectories. Based upon estimated intercepts and slopes for each trajectory, the 5 IPV trajectories were interpreted as low or no, low to moderate, moderate to low, high to moderate, and high to increasing. This distribution of trajectories suggests college women have very diverse experiences with IPV; it also indicates the frequency of IPV dramatically changes across time for most women affected. The period between adolescence and the end of the first year of college seems to be where most of the change occurs, in both positive and negative directions.

Our second goal was to predict trajectory membership with negative childhood experiences. Women who were victims of childhood physical abuse are more likely to be in the trajectory characterized by frequent and consistent IPV—findings consistent with the revictimization literature.8–10 Childhood sexual abuse predicted membership in all 4 elevated IPV trajectories, underscoring its central role in future victimization experiences. Witnessing domestic violence predicted membership in the high to moderate trajectory and childhood physical abuse predicted membership in the high to increasing trajectory, the 2 most worrisome trajectories.

IMPLICATIONS

The ultimate goal of this research is to decrease or even prevent IPV. To prevent IPV, we must understand patterns of risk. Our analyses suggest how IPV risk can change over time for different groups of women. Many IPV prevention and intervention programs are indiscriminately applied with the belief that all girls and women are at relatively equal risk of becoming victims, although the literature has indicated otherwise for some time.4,5 Differential patterns of IPV apparent in our data suggest the need for prevention strategies for women that consider victimization experiences in childhood and early adulthood. Future investigation should focus on other childhood variables predicting future IPV trajectories, such as family income, parents’ education, and the presence of substance use in the home. Future research should also assess factors leading to these increases and decreases in IPV shortly after college matriculation to better understand IPV risk and protective factors.

LIMITATIONS

All data used for these analyses were collected from students at 1 Southeastern university. Although the Carnegie Foundation has found students at this institution to be representative of all students at U.S. state colleges and universities,25 the findings of this study may not generalize to all female U.S. college students, students from other countries, or non-college populations. The IPV literature does not suggest trajectories would differ across subpopulations of women; however, caution should be used in generalizing these findings. Another limitation of this work was its primary focus on the frequency of women’s IPV experiences. By limiting the scope of the current research to frequency of victimization, all IPV experiences are given the same weight in the analysis. Future research designs that include examinations of IPV severity or other assault characteristics will extend the current findings. Finally, witnessing domestic violence and physical abuse during childhood each were measured with 1 item; future research should use validated measures including multiple items to assess each construct.

CONCLUSION

The present study makes the case for subgroups of college women in terms of their patterns of IPV frequency across time. LCGA identified 5 classes across adolescence and 4 years of college. These 5 classes are interpreted as low or no, low to moderate, moderate to low, high to moderate, and high to increasing IPV trajectories of victimization across time. Negative childhood experiences—childhood sexual abuse, witnessing domestic violence, and parental physical punishment—distinguished between the latent trajectories. Application of research that distinguishes cohesive subgroups of victims may inform the disparate efforts of IPV prevention programs.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Monica H Swahn, PhD, MPH

Submission history: Submitted January 18, 2012; Revision received March 11, 2012; Accepted March 17, 2012

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

DOI: 10.5811/westjem.2012.3.11788

Address for Correspondence: Kevin M Swartout, PhD

Georgia State University, Atlanta, Georgia

Email: kswartout@gsu.edu

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: 2011. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. In.

2. Schwartz MD. Gender and injury in spousal assault. Sociological Focus. 1987;3:239–248.

3. Bachman R, Saltzman LE. U. S. Department of Justice. Washington DC: 1994. Violence against women: Estmates from the redesigned survey. In.

4. Walby S, Allen J. Home Office Research Study 276. London, England: 2004. Domestic violence, sexual assault and stalking: Findings from the British crime survey.

5. Foa EB, Cascardi M, Zoellner LA, Feeny NC. Psychological and environmental factors associated with partner violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2000;1(1):67–91.

6. Bennett Cattaneo L, Goodman LA. Risk factors for reabuse in intimate partner violence: A cross-disciplinary critical review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2005;6(2):141–175.

7. Kuijpers KF, van der Knaap LM, Lodewijks IAJ. Victims’ influence on intimate partner violence revictimization: A systematic review of prospective evidence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse.2011;12(4):198–219.

8. Koverola C, Proulx J, Battle P, Hanna C. Family functioning as predictors of distress in revictimized sexual abuse survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1996;11(2):263–280.

9. Tusher CP, Cook SL. Comparing revictimization in two groups of marginalized women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25(10):1893–1911. [PubMed]

10. Messman-Moore TL, Long PJ, Siegfried NJ. The revictimization of child sexual abuse survivors: An examination of the adjustment of college women with child sexual abuse, adult sexual assault, and adult physical abuse. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5(1):18–27. [PubMed]

11. Nagin DS. Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group-based approach.Psychological Methods. 1999;4(2):139–157.

12. Swartout AG, Swartout KM, White JW. What your data didn’t tell you the first time around: Advanced analytic approaches to longitudinal analyses. Violence Against Women. 2011;17(3):309–321.

13. Swartout KM, Swartout AG, White JW. A person-centered, longitudinal approach to sexual victimization. Psychology of Violence. 2011;1(1):29–40.

14. Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1979;41(1):75–88.

15. Straus MA. Cross-cultural reliability and validity of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales: A study of university student dating couples in 17 nations. Cross-Cultural Research: The Journal of Comparative Social Science. 2004;38(4):407–432.

16. Koss MP, Gidycz CA, Wisniewski N. The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55(2):162–170. [PubMed]

17. Mplus (Version 5.1) Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2008. computer program.

18. McKnight PE, McKnight KM, Sidani S, Figueredo AJ. Missing data: A gentle introduction. New York, NY US: Guilford Press;; 2007.

19. White JW, Smith PH. Covariation in the use of physical and sexual intimate partner aggression among adolescent and college-age men: A longitudinal analysis. Violence Against Women.2009;15(1):24–43. [PubMed]

20. Long JS. Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc;; 1997.

21. Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Schulenberg JE. Conjoint developmental trajectories of young adult alcohol and tobacco use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114(4):612–626. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

22. Tucker JS, Orlando M, Ellickson PL. Patterns and correlates of binge drinking trajectories from early adolescence to young adulthood. Health Psychology. 2003;22(1):79–87. [PubMed]

23. Muthén B. Latent variable analysis: Growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D, editor. Handbook of quantitative methodology for the social sciences.Newbury Park, CA: Sage;; 2004. In. ed.

24. Muthén B. Statistical and substantive checking in growth mixture modeling: Comment on Bauer and Curran (2003) Psychological Methods. 2003;8(3):369–377. [PubMed]

25. The Carnegie Foundation. A classification of institutions of higher education. Princeton, NJ: 1987.