| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Jose V. Nable, MD | University of Maryland Baltimore County, Department of Emergency Health Services, Baltimore, Maryland |

| John C. Greenwood, MD | University of Maryland School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland |

| Michael K. Abraham, MD | University of Maryland School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland |

| Michael C. Bond, MD | University of Maryland School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland |

| Michael E. Winters, MD | University of Maryland School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland |

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

ABSTRACT

Introduction

There is scant literature regarding the optimal resident physician staffing model of academic emergency departments (ED) that maximizes learning opportunities. A department of emergency medicine at a large inner-city academic hospital initiated a team-based staffing model. Its pre-interventional staffing model consisted of residents and attending physicians being separately assigned patients, resulting in residents working with two different faculty providers in the same shift. This study aimed to determine if the post-interventional team-based system, in which residents were paired with a single attending on each shift, would result in improved residents’ learning and clinical experiences as manifested by resident evaluations and the number of patients seen.

Methods

This retrospective before-and-after study at an academic ED with an annual volume of 52,000 patients examined the mean differences in five-point Likert-scale evaluations completed by residents assessing their ED rotation experiences in both the original and team-based staffing models. The residents were queried on their perceptions of feeling part of the team, decision-making autonomy, clinical experience, amount of supervision, quality of teaching, and overall rotational experience. We also analyzed the number of patients seen per hour by residents. Paired sample t-tests were performed. Residents who were in the program in the year preceding and proceeding the intervention were eligible for inclusion.

Results

34 of 38 eligible residents were included (4 excluded for lack of evaluations in either the pre- or post-intervention period). There was a statistically significant improvement in resident perception of the quality and amount of teaching, 4.03 to 4.27 (mean difference=0.24, p=0.03). There were non-statistically significant trends toward improved mean scores for all other queries. Residents also saw more patients following the initiation of the team-based model, 1.24 to 1.56 patients per hour (mean difference=0.32, p=0.0005).

Conclusion

Adopting a team-based physician staffing model is associated with improved resident perceptions of quality and amount of teaching. Residents also experience a greater number of patient evaluations in a team-based model.

INTRODUCTION

Duty-hour restrictions imposed on resident physicians challenge residency programs to develop clinical experiences that meet patients’ needs as well as trainees’ educational requirements. The implementation of work hour rules forces residency programs to maximize learning opportunities for their residents. The Residency Review Committee in Emergency Medicine (RRC-EM) has adopted a 60-hour clinical work week, which is more restrictive than the 80-hour limit of the American College of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).1 Emergency medicine residency programs are therefore confronted with a need to take full advantage of a limited amount of time to teach physicians-in-training. Little has been published about the effect of emergency department (ED) physician staffing models on learners’ attitudes and perceptions.

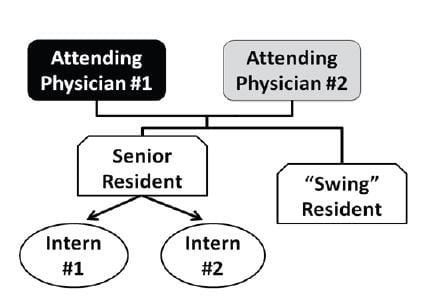

In 2012, our EM residency program, located at an academic medical center, adopted a new resident staffing model for our ED. The previous staffing model included two faculty physicians, one senior resident, two interns, and one “swing” resident. The two faculty physicians geographically split the 30-bed acute ED. Urgent care patients are seen in a separate part of the studied ED; the described staffing changes did not affect the urgent care area. A senior resident in his or her final year of EM training supervised the two interns. Patients were assigned to the interns on an alternating basis. The swing resident, a PGY2 or PGY3+ resident, took responsibility for the most critically ill patients in the ED to decompress the workload on the interns by assuming responsibility for a fraction of the patients initially assigned to them. Because the attending physicians’ bed assignments were determined geographically and the interns were assigned patients on an alternating basis, each intern had the opportunity to work with two faculty physicians on the same shift. The original staffing model is depicted in Figure 1.

Since the swing resident was not directly assigned patient beds but was expected to self-select patients, the amount of intern load-leveling was highly dependent on the efficiency, speed, and motivation of the swing resident. A highly efficient resident was obviously more likely to lessen the interns’ patient load. The number of patients seen by a resident on a shift has been shown to be directly related to perceived stress.2 We realized that the line of responsibility needs to be clearly delineated, because communication in a busy ED is complex, requiring multiple interactions among staff members for each patient.3 In this model, only the attending was confined geographically, making it difficult for nurses to identify which resident was assigned to an individual patient. Finally, because residents worked with two attending physicians at the same time, the learning environment was less conducive to individualized instruction.4,5

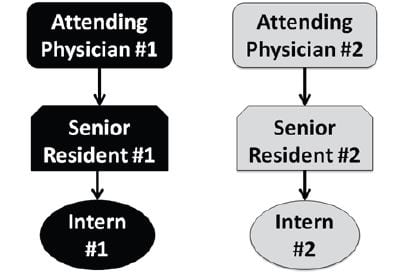

After soliciting input from residents, nursing staff, and faculty physicians, we designed a new staffing model, which was implemented in June 2012. In this new team-based approach, the ED is divided geographically between two teams. Each team consists of an attending physician, an upper-level (PGY2 or PGY3+) resident, and an intern. The new staffing model is depicted in Figure 2. We hypothesized that this new team-based system would improve residents’ learning and clinical experiences, as manifested by higher rotation evaluation scores. We further hypothesized that the elimination of the “swing” resident, in favor of a second senior resident responsible for a defined set of ED beds, would result in an increase in patient exposure as manifested by higher patients seen per hour. This article describes the effects of the change in ED staffing.

METHODS

Study Design

This retrospective before-and-after study was based on de-identified data that were collected from an electronic resident evaluation system and an electronic patient tracking system. The study design was reviewed and approved by our institutional review board.

Study Setting and Population

The study site is a 30-bed urban academic ED with 52,000 patient visits per year and a 20% admission rate. We include in the study EM residents who worked in our ED between November 12, 2011, and April 28, 2013, with at least one rotation in both the pre- and post-intervention periods.

Study Protocol

In EM residency program, all residents evaluate each of their rotations. We obtained data for this study using an Internet-based electronic evaluation tool, E*Value (Minneapolis, Minnesota), which solicits and collects resident evaluations every 4 weeks. Data were de-identified and examined in aggregate so as to not attribute any evaluation score to an individual.

The new team-based staffing model was implemented on June 24, 2012, the beginning of an academic year. Evaluations submitted by residents rotating in the ED between November 14, 2011, and June 23, 2012, were considered pre-intervention evaluations. Residents are assigned to the ED on 4-week block rotations; a total of eight 4-week blocks were included in the pre-intervention period. Three 4-week block rotations (June 24 to September 16, 2012) following institution of the new staffing model were considered a washout period to minimize effects introduced by staff members’ adjustment to the change and the “July phenomenon,” the tendency toward increased errors and decreased hospital efficiency at teaching hospitals at the start of the academic year.6 Evaluations completed during the eight 4-week blocks between September 17, 2012, and April 28, 2013, were considered the post-intervention group.

Additionally, we determined the number of patients seen by each resident in the pre-intervention and post-intervention periods using a reporting function available through the study site’s electronic patient tracking system FirstNet (Cerner, North Kansas City, Missouri). Resident work hours were retrieved via an electronic physician shift scheduling software OnCall (Spiral Software, Newton, Massachusetts).

Measures

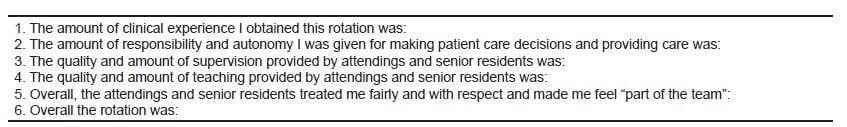

A five-point Likert scale was used to query all residents about their experience in the ED at the conclusion of their rotation. The questions that are the focus of this study are listed in Figure 3, as is the scale used by the residents to indicate their responses. The quantity of patient exposure by residents was measured as patients per hour (PPH).

Figure 3

Resident evaluation questions examined in this study in which all responses were on a scale of 1–5: 1, poor; 2, below average; 3, average; 4, above average; 5, exceptional.

Data Analysis

We included in the final analysis evaluations and PPH by residents who rotated in the ED in both the pre-intervention and post-intervention. The mean Likert scale scores for evaluations completed by the residents and PPH were calculated. We determined mean differences and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) between both periods among all residents using paired sample t-tests. Statistician 2.0 (xlQA, Melbourne, Australia) was used for data analysis.

RESULTS

Out of 38 residents who were in the program during both the pre- and post-intervention periods, evaluations were completed for both periods by 34 residents. To allow for paired sample t-tests, we included in the study analysis only those 34 residents who rotated in the ED in both periods and completed evaluations.

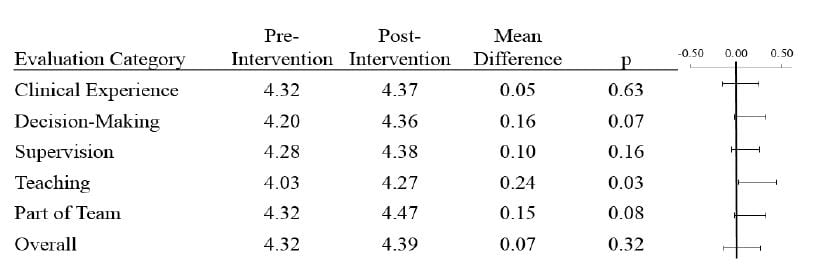

The mean Likert scale scores are presented in Figure 4. Following the initiation of the team-based staffing model, there was a statistically-significant increase in the mean scores for the query regarding the quality and amount of teaching, which improved from 4.03 to 4.27 (mean difference=0.24, p=0.03). There were non-statistically significant trends toward improved mean scores for all other queries.

Residents (PGY-2+) saw more patients following the initiation of the team-based model (Table). Prior to the team-based staffing system, residents saw an average of 1.24 PPH, with an increase to 1.56 PPH post-intervention (mean difference=0.32, p=0.0005, 95% confidence interval [0.17 to 0.47])).

Figure 4

Mean evaluation responses by residents are shown. Each category corresponds to the questions in Figure 3 posed to each resident, who responded using a five-point Likert scale. Mean differences between the pre-intervention and post-intervention periods are calculated and 95% confidence intervals shown on the right.

Table. Resident productivity as measured by patients evaluated per hour (mean difference=0.32, p=0.0005).

| Patients per hour | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 1.24 | 1.56 |

| SD | ± 0.36 | ± 0.39 |

SD, standard deviation

DISCUSSION

In today’s EM environment, characterized by high patient acuity, increasing patient volumes, and an emphasis on fast throughput, the time available for individual patient care and clinical education is often limited.7 This constraint is particularly important in the chaotic environment of the ED, where workloads are unpredictable and physicians are interrupted frequently.8,9 Team-based learning is a powerful pedagogical tool that has been classically applied to didactic teaching.10 Incorporating this type of educational tool into the clinical setting may improve residents’ clinical experience and education. By applying a vigorous qualitative analysis to self-reports, we have identified several areas that residents perceive as improved after moving to a team-based physician-staffing model.

EM residents value participation in the work environment, focused learning moments, repetitive teaching cycles, and intense learning experiences.11 We feel that the structure of the clinical work environment, specifically using the physician-staffing model, might have a significant impact on learners’ attitudes and perceptions about their clinical experience.

Qualitative reports and expert opinion regarding improvements in medical education have been well documented.12 In this study, moving from a staffing model led by senior residents to one based on teams trended toward a higher number of favorable responses to subjective questions related to residents’ clinical experience in the ED. Significant improvements were found in subgroups related to patient care decisions, clinical experience, and teaching.

Our residents’ evaluations of their experience generally trended towards improved scores following the initiation of a team-based model. In our previous staffing model, the swing resident managed the most critically ill patients in the ED. In the team-based model, a number of changes could account for residents’ improved attitudes about their clinical experience. First, team leaders were upper-level residents paired with a single attending and intern throughout an entire shift, which reduced confusion related to patient assignment during a busy clinical shift. Second, team leaders were expected to see a higher volume of patients during a given shift, as they were given a large and specific geographic responsibility within the ED (in contrast to the previous model’s swing resident, who assumed care for patients at his or her own pace). And, third, having an intern available in the team-based structure allowed the senior resident to share tasks, such as arranging follow-up, calling consults, and documenting patient care. Having the option to share these responsibilities might enhance residents’ perceptions of their clinical experience.

Perceptions of teaching quality significantly improved when the swing and team-based approaches were compared. A number of previous studies found that faculty members have a limited amount of direct interaction and observation of EM residents.13,14 We believe the team-based staffing model allows a higher-degree of interaction between faculty physicians and residents, increasing teaching efficiency. Managing patients using a team-based approach also encourages residents to discuss patient care decisions together more frequently, which encourages active participation, learning, and more efficient communication of “teachable moments” among multiple learners. Many of these techniques have been described as effective learning techniques.15

Additionally, there was a significant improvement in the number of patients seen by the residents (PGY-2+) following the initiation of the team-based model. In the previous model, the swing resident could self-select his patients. Individual resident motivation and efficiency likely affected the number of patient evaluations. In the team-based model, however, the two senior residents geographically split the ED, reducing the ability of slower residents to select a fewer number of patients.

Further research by our department will likely incorporate more specifically intern-level experience. The electronic patient tracking system used in our ED during the study period allowed associating only residents (PGY-2+) to patients. Interns were therefore not included in the resident productivity analysis. Since our patient tracking system now records patients evaluated by interns, how the educational experience of these first-year physicians is affected by staffing model changes can be more readily examined. The addition of a teaching resident in the staffing model, whose role is to provide more comprehensive and complimentary instruction of interns and medical students, will likely be studied.

LIMITATIONS

A significant limitation of this study is that we used a non-validated survey tool to measure residents’ responses. Our findings are based on self-reported perceptions and therefore do not directly measure any quantitative outcomes within the chosen survey categories. Although the ACGME Common Program Requirements mandate that resident feedback be used in assessing multiple aspects of a residency program’s educational experiences,16 there is currently no uniform approach to obtaining such evaluative measures. The observed effects in resident perceptions of their ED educational experience may have varied had the queries been worded differently. The survey instrument used in this study, however, has been used at our institution for the last five years, allowing the program to internally ascertain trends. As a further limitation, residents were also not required to complete the survey until the rotation ended, so recall bias might have influenced their responses. Also, the increase in number of patients seen in the post-intervention staffing model may be a reflection of the improved efficiency expected of residents who are farther into their training program. Finally, this study did not examine effects on patient outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Data are scarce regarding the effect of physician staffing models on residents’ attitudes and perceptions about their clinical experience. Our results demonstrate that adopting a team-based physician staffing model can improve residents’ perceptions about their educational experience. Our study also demonstrated that a team-based model was associated with an increased number of patient evaluations as compared to a staffing model in which residents could self-select their patients. We hope that the results from this study will be helpful in the development of ED physician staffing models that improve the teaching environment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge Linda J. Kesselring, MS, ELS, the technical editor/writer in the Department of Emergency Medicine University of Maryland School of Medicine, for her contributions as copyeditor of the manuscript. The authors further acknowledge Michael Taigman, MA, instructor in the Department of Emergency Health Services University of Maryland Baltimore County for his guidance on this project.

Footnotes

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Jose Nable, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine. Email: jnable@umem.org. 9 / 2014; 15:682 – 686

Submission history: Revision received December 14, 2013; Accepted May 5, 2014

Conflicts of Interest: By the West JEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1 Wagner MJ, Wolf S, Promes S Duty hours in emergency medicine: balancing patient safety, resident wellness, and the resident training experience: a consensus response to the 2008 institute of medicine resident duty hours recommendations. Acad Emerg Med. 2010; 17:1004-11

2 Wrenn K, Lorenzen B, Jones I Factors affecting stress in emergency medicine residents while working in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2010; 28:897-902

3 Patterson PD, Pfeiffer AJ, Weaver MD Network analysis of team communication in a busy emergency department. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013; 13:109

4 Kelly SP, Shapiro N, Woodruff M The effects of clinical workload on teaching in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2007; 14:526-31

5 Penciner R Clinical teaching in a busy emergency department: strategies for success. CJEM. 2002; 4:286-8

6 Inaba K, Recinos G, Teixeira PG Complications and death at the start of the new academic year: is there a July phenomenon?. J Trauma. 2010; 68:19-22

7 Cohen JJ Heeding the plea to deal with resident stress. Ann Intern Med. 2002; 136:394-5

8 Chisholm CD, Dornfeld AM, Nelson DR Work interrupted: a comparison of workplace interruptions in emergency departments and primary care offices. Ann Emerg Med. 2001; 38:146-51

9 Levin S, France DJ, Hemphill R Tracking workload in the emergency department. Hum Factors. 2006; 48:526-39

10 Haidet P, O’Malley KJ, Richards B An initial experience with “team learning” in medical education. Acad Med. 2002; 77:40-4

11 Goldman E, Plack M, Roche C Learning in a chaotic environment. J Workplace Learning. 2009; 21:555-74

12 Irby DM What clinical teachers in medicine need to know. Acad Med. 1994; 69:333-42

13 Burdick WP, Schoffstall J Observation of emergency medicine residents at the bedside: how often does it happen?. Acad Emerg Med. 1995; 2:909-13

14 Chisholm CD, Whenmouth LF, Daly EA An evaluation of emergency medicine resident interaction time with faculty in different teaching venues. Acad Emerg Med. 2004; 11:149-55

15 Bandiera G, Lee S, Tiberius R Creating effective learning in today’s emergency departments: how accomplished teachers get it done. Ann Emerg Med. 2005; 45:253-61

16 . Common Program Requirements. 2013;