| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Regina A. Kovach, MD | Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Departments of Medicine and Surgery, Divisions of General Internal Medicine and Emergency Medicine, Springfield, IL |

| David L. Griffen, MD, PhD | Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Departments of Medicine and Surgery, Divisions of General Internal Medicine and Emergency Medicine, Springfield, IL |

| Mark L. Francis, MD | Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Departments of Medicine and Surgery, Divisions of General Internal Medicine and Emergency Medicine, Springfield, IL |

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

Faculty often evaluate learners in the emergency department (ED) at the end of each shift. In contrast, learners usually evaluate faculty only at the end of a rotation. In December 2007 Southern Illinois University School of Medicine changed its evaluation process, requiring ED trainees to complete end-of-shift evaluations of faculty. Determine the feasibility and acceptance of end-of-shift evaluations for emergency medicine faculty.

Methods:

We conducted this one-year observational study at two hospitals with 120,000 combined annual ED visits. Trainees (residents and students) anonymously completed seven-item shift evaluations and placed them in a locked box. Trainees and faculty completed a survey about the new process.

Results:

During the study, trainees were assigned 699 shifts, and 633 end-of-shift evaluations were collected for a completion rate of 91%. The median number of ratings per faculty was 31, and the median number of comments was 11 for each faculty. The survey was completed by 16/22 (73%) faculty and 41/69 (59%) trainees. A majority of faculty (86%) and trainees (76%) felt comfortable being evaluated at end-of-shift. No trainees felt it was a time burden.

Conclusion:

Evaluating faculty following an ED shift is feasible. End-of-shift faculty evaluations are accepted by trainees and faculty.

INTRODUCTION

Exceptional teaching improves learner outcomes.1–3 Identifying good teachers and improving the skills of all teachers, therefore, have important implications for medical learners. Similarly, determining those whose skills need improvement is an obligation of program and course directors. Learners are a valid judge of teaching skills, but assessment of clinical teachers in the emergency department (ED) usually occurs at the end of a clinical rotation at a time distant from the actual teaching encounter.4–6 Furthermore, end-of-rotation evaluations commonly focus on topics such as organization, clarity of objectives and fairness in grading, rather than on each faculty’s teaching performance.7 The result is that end-of-rotation evaluation systems may provide little specific information or feedback about the teaching performance of individual faculty. Ideally, the evaluation of clinical teachers by learners would focus on the teaching abilities of the individual teacher and would be part of a system in which enough evaluations are collected to provide reliable measures of teacher performance. Eight to 20 trainee evaluations are needed to achieve reproducible, dependable estimates of teaching performance.4,8–12 Given that residents and students may encounter some clinicians infrequently, if rotation evaluations are the primary source for teaching evaluations, several years may be required to achieve a reliable estimate of an individual teacher’s performance.12

The teaching and learning environment in an ED is unique and particularly challenging because patient volumes and levels of acuity are unpredictable, and trainees may be exposed to teaching faculty sporadically for different amounts of time. Although resident and student performance is often evaluated at the conclusion of each shift by supervising faculty, we are unaware of any published information that describes the evaluation of emergency medicine (EM) faculty at the end of a shift.13–15 We hypothesized that evaluating an instructor at the end of a teaching shift would be feasible in a busy ED. Our aim was to develop an end-of-shift faculty evaluation form that emphasized observations made in the routine conduct of clinical teaching, and was confidential and acceptable to teachers and learners.16 In December 2007 Southern Illinois University School of Medicine (SIU SOM) changed its evaluation process, requiring residents and students rotating in the ED to complete end-of-shift evaluations of supervising faculty.

The objective of this study is to determine the feasibility and acceptance of evaluating EM faculty at the end of clinical shifts.

METHODS

Study Design

This is an observational feasibility study conducted at two medical school-affiliated teaching hospitals. The project received approval from the SIU SOM Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects and approval by the institutional review board for both hospitals and the SOM.

Study Setting and Population

SIU SOM is a community-based medical school with 72 students per class affiliated with two large tertiary care teaching hospitals. There are 25 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education approved residency and fellowship programs at SIU SOM, and the Residency Review Committee approved an EM residency program in September 2009. We conducted this study at the EDs of both affiliated hospitals with a combined annual ED visit volume greater than 120,000. Two separate physician groups staff each ED, and the departments do not share faculty. Subjects were residents rotating on the EM service from the departments of Internal Medicine, Family Medicine, Orthopedics and Obstetrics and Gynecology; junior and senior students on an EM elective; and faculty supervisors in both hospital EDs.

Study Protocol

During orientation to the EM rotation, students and residents are informed they will evaluate the teaching skills of faculty at the end of each shift, and are given a pocket-sized packet of evaluation forms. They are taught how to complete the forms, and are told that the evaluations are anonymous and should be placed in a locked box in the ED at the conclusion of each shift. The authors developed the evaluation form by consensus; it has seven items rated on an eight-point Likert scale and includes space for comments (Figure 1). Four items on the form address easily observable behaviors, (for example, “Did the faculty ask you questions about your patients?”), one item asks an opinion of self learning (“Did faculty instruction contribute to your fund of knowledge?”), and one requests a global assessment (“How would you rate the faculty as a teacher?”). The specific items on the form were selected because they are desired behaviors in our faculty teachers and viewed as relevant for both student and resident learners. We included teaching behaviors that could easily be observed in one shift and were amenable to feedback and faculty improvement. The form was not pilot tested. An administrative assistant collected the forms weekly and entered both the numerical ratings and comments in an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Inc., Redmond, WA). Twice yearly, faculty receive the mean rating of their evaluations, the mean rating of their peers, and specific comments from their evaluations.

To accomplish the study objective we analyzed end-of-shift evaluations completed by residents and students during the 12-month study period. In addition, residents, students and faculty voluntarily and anonymously completed web-based opinion surveys about the new process (SurveyMonkey.com, Portland, OR). The survey was developed by consensus among the authors. The faculty survey contained four items, and the trainee survey contained five items. All survey inquiries asked for responses on a five-point Likert scale, except one. A “yes/no” response was sought for an item that asked trainees and faculty if they had prior experience evaluating or being evaluated immediately after a clinical experience. We included the link to the surveys in an E-mail request sent to all trainees and faculty. We decided a priori to conclude the process was feasible and acceptable if trainees completed the evaluations greater than 75% of the time and if greater than 75% of faculty and trainees indicated on the surveys they were comfortable with the process.

We performed qualitative content analysis of comments written on end-of-shift evaluations using an iterative process. One author (RK) and a research assistant reviewed and categorized the comments into strengths and weaknesses and whether they referenced modifiable behaviors (e.g. “gave good feedback”) or non-specific personality or department characteristics (e.g. “smart guy” or “slow day”). They then subcategorized them into themes, and any disagreement was resolved by consensus.

RESULTS

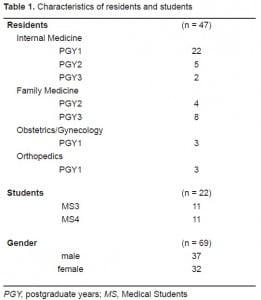

Of the 22 faculty attendings evaluated during the study period, 18 (82%) were men and four (18%) were women. The majority of faculty (17/22, 77%) had been in practice for greater than ten years. Sixty-nine trainees (47 residents and 22 students) completed the end-of-shift evaluations. Demographic characteristics of the trainees are included in Table 1.

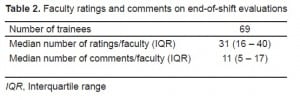

During the 12-month period, trainees were assigned 699 shifts, and 633 end-of-shift evaluations were collected, resulting in a completion rate of 91%. There was a median of 31 ratings per faculty (interquartile range [IQR]; 16 – 40). The majority of faculty (73%) had more than 20 evaluations. Trainees wrote a median number of 11 (IQR 5 – 17) comments per faculty (Table 2).

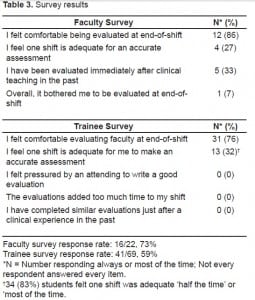

The response rates for the faculty and student surveys were 73% (16/22) and 59% (41/69) respectively (Table 3). The majority of faculty (86%) and trainees (76%) were comfortable with end-of-shift evaluations. When asked if one shift was enough exposure to make an accurate assessment, a minority of faculty (27%) and trainees (33%) responded “always” or “almost always,” although 51% of trainees indicated that one shift was adequate “about half the time.” None of the trainees had prior experience assessing faculty immediately following a clinical experience, and none found the end-of shift evaluations a time burden.

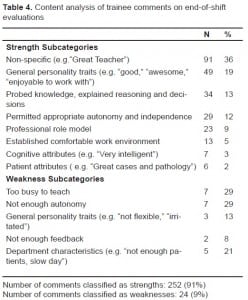

Trainees wrote 276 comments on the end-of-shift evaluations. There were 252 comments categorized as strengths and 24 as weaknesses (Table 4). A majority (168/276, 61%) cited general, non-specific characterstics of faculty or departments, such as “pleasant to be around,” or “great patients.” Less than 40% (108/276) focused on specifc teaching behaviors, for example, “let me know how he was thinking,” or “didn’t let me do anything.” Themes addressing favorable personality traits, good teaching in general, probing of knowledge and decision making, and permitting trainee autonomy were most often spontaneously reported.

DISCUSSION

We were pleased to see that in a one-year period almost three-quarters of our faculty had received more than 20 evaluations, a number that many investigators report as sufficient to make a reliable estimate of performance. Since learner evaluations of clinical teaching have a major impact on faculty self-improvement and career advancement,4,16 it is important that they accurately reflect a teacher’s effectiveness. One might question the usefulness of the end-of-shift evaluations since only 51% of learners felt they could accurately assess faculty after one shift “about half the time.” Although we did not specifically measure reliability, we are encouraged with the numbers of evaluations obtained for each teacher, and our opinion is that as the numbers of daily evaluation cumulatively increase over time, the likelihood of providing reliable feedback to faculty improves. We plan to study the reliability of the process in the future. Many comments were provided on the end-of-shift evaluations, and almost 40% of these comments contained specific feedback targeting modifiable behaviors of value to teachers. More than half of the comments, however, expressed non-specific sentiments such as “great teacher” or “a pleasure to work with,” which are less helpful for guiding teacher improvement. Since some trainees believe they are not taught to evaluate teaching performance, we view this as an excellent opportunity to educate students and residents in this regard.17 We plan to enhance the orientation of learners by addressing not only how to complete the form but by including training on how to evaluate teaching, give effective feedback, and by emphasizing the importance of writing comments directed toward specific instructional behaviors.

We are unaware of any published information that addresses whether faculty evaluations completed immediately after a clinical experience are congruent with those done at the end of a rotation. One might speculate that end-of-shift evaluations, completed when the teaching encounter is fresh in memory, would provide more factual information about a teacher’s effectiveness, and ratings on end-of-rotation evaluations might be less valuable if they represent a particularly memorable teaching experience, whether good or bad. Another view, however, is that an end-of-rotation evaluation may be superior to end-of-shift evaluations if it reflects a trainee’s synthesis of experiences in the ED over time and takes into account comparisons with other teachers. While these points were not the focus of our project, we feel they are worthy of future investigation.

We wanted the faculty shift evaluations to be operationally feasible. We were concerned that faculty might object to being scrutinized daily or trainees might feel coerced to write a favorable evaluation after working closely with one clinician for an entire shift. We felt it was possible that trainees would not comply with the process of evaluating faculty at end-of-shift, if they found the process time consuming or objectionable for other reasons. The high completion rate and survey data demonstrated, however, that trainee assessment of teachers at the end of a shift is feasible and readily accepted by both teachers and learners in the ED. We believe that by instituting a process whereby faculty and trainees are both evaluated in the same fashion (end-of-shift) we emphasize that teaching and learning are equally important, and hope the process has had a positive impact on the educational culture in our EDs.

Ultimately, one of the most important goals of assessing clinical teaching performance is to improve the skills of weaker teachers. It has been shown that when clinical teachers are provided periodic ratings of their teaching performance together with mean ratings of their colleagues, teaching skills improve.18 Our evaluation process has not been in place long enough to confirm these findings, but we plan to study whether sharing the data from end-of-shift evaluations along with peer comparisons will help us provide meaningful feedback to faculty and result in improved teacher performance.

LIMITATIONS

There are limitations to this study. First, it was conducted at two large hospital EDs at one medical school, and our findings may not generalize to other institutions. Second, the study period was one year, and we did not assess the long-term acceptance of the evaluation process. Third, the participating residents were not EM residents, and there may be differences in how EM residents rate EM faculty compared to medical students and residents from other departments. Fourth, similar to most institutions, trainees were not formally taught how to evaluate faculty.17 This lack of training may have positively or negatively influenced actual faculty ratings, completion rates of the daily evaluations, and responses on the acceptance survey.

CONCLUSION

We found that faculty end-of-shift evaluations are feasible in a busy ED and are accepted by trainees and faculty. We believe end-of-shift evaluations of faculty are potentially a valuable tool for assessing faculty teaching effectiveness and warrant further study.

Footnotes

We thank Kate Beasley for her help with comment analysis, data entry and manuscript preparation.

Supervising Section Editor: Gene Hern Jr., MD

Submission history: Submitted January 5, 2010; Revision Received May 3, 2010; Accepted May 10, 2010

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Regina A. Kovach, MD, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, 701 North First Street — Room C402, PO Box 19636, Springfield, Illinois 62794-9636

Email: rkovach@siumed.edu

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Blue AV, Griffith CH, 3rd, Wilson J, et al. Surgical teaching quality makes a difference. Am J Surg.1999;177:86–9. [PubMed]

2. Griffith CH, 3rd, Georgesen JC, Wilson JF. Six-year documentation of the association between excellent clinical teaching and improved students’ examination performances. Acad Med.2000;7:S62–4. [PubMed]

3. Stern DT, Williams BC, Gill A, et al. Is there a relationship between attending physicians’ and residents’ teaching skills and students’ examination scores? Acad Med. 2000;75:1144–6. [PubMed]

4. Irby D, Rakestraw P. Evaluating clinical teaching in medicine. J Med Educ. 198;56:181–6.[PubMed]

5. Steiner IP, Franc-Law J, Kelly KD, et al. Faculty evaluation by residents in an emergency medicine program: a new evaluation instrument. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1015–21. [PubMed]

6. Williams BC, Litzelman DK, Babbott SF, et al. Validation of a global measure of faculty’s clinical teaching performance. Acad Med. 2002;77:177–80. [PubMed]

7. Kogan JR, Shea JA. Course evaluation in medical education. Teaching and Teacher Education.2007;23:251–64.

8. Hayward RA, Williams BC, Gruppen LD, et al. Measuring attending physician performance in a general medicine outpatient clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:504–10. [PubMed]

9. James PA, Kreiter CD, Shipengrover J, et al. A generalizability study of a standardized rating form used to evaluate instructional quality in clinical ambulatory sites. Acad Med. 2001;76:S33–5.[PubMed]

10. Mazor K, Clauser B, Cohen A, et al. The dependability of students’ ratings of preceptors. Acad Med. 1999;74:S19–21. [PubMed]

11. Ramsbottom-Lucier MT, Gillmore GM, Irby DM, et al. Evaluation of clinical teaching by general internal medicine faculty in outpatient and inpatient settings. Acad Med. 1994;69:152–4. [PubMed]

12. Solomon DJ, Speer AJ, Rosebraugh CJ, et al. The reliability of medical student ratings of clinical teaching. Eval Health Prof. 1997;20:343–52. [PubMed]

13. Bandiera G, Lendrum D. Daily encounter cards facilitate competency-based feedback while leniency bias persists. CJEM. 2008;10:44–50. [PubMed]

14. University of Michigan Health System Web site. [Accessed January 5, 2010]. Available at:http://www.med.umich.edu/em/education/requirements.htm.

15. Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine Web site. [Accessed January 5, 2010]. Available at: http://www.med.wright.edu/ortho/res/emergency.html.

16. Snell L, Tallett S, Haist S, et al. A review of the evaluation of clinical teaching: new perspectives and challenges. Med Educ. 2000;34:862–70. [PubMed]

17. Alfonso NM, Cardoza LJ, Mascarenasas OA, et al. Are anonymous evaluations a better assessment of faculty teaching performance? A comparative analysis of open and anonymous evaluation processes. Family Medicine. 2005;37:43–7. [PubMed]

18. Maker VK, Lewis MJ, Donnelly MB. Ongoing faculty evaluations: developmental gain or just more pain? Curr Surg. 2006;63:80–4. [PubMed]