| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Nese C. Oray, MD | Dokuz Eylul University, School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Izmir, Turkey |

| Semra Sivrikaya, MD | Dokuz Eylul University, School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Izmir, Turkey |

| Basak Bayram, MD | Dokuz Eylul University, School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Izmir, Turkey |

| Tufan Egeli, MD | Dokuz Eylul University, School of Medicine, Department of Genergal Surgery, Izmir, Turkey |

| Oguz Dicle, MD | Dokuz Eylul University, School of Medicine, Department of Radiology, Izmir, Turkey |

ABSTRACT

Traumatic perforation of the esophagus due to blunt trauma is a rare thoracic emergency. The most common causes of esophageal perforation are iatrogenic, and the upper cervical esophageal region is the most often injured. Diagnosis is frequently determined late, and mortality is therefore high. This case report presents a young woman who was admitted to the emergency department (ED) with esophageal perforation after having fallen from a high elevation. Esophageal perforation was diagnosed via thoracoabdominal tomography with ingestion of oral contrast. The present report discusses alternative techniques for diagnosing esophageal perforation in a multitrauma patient.

CASE

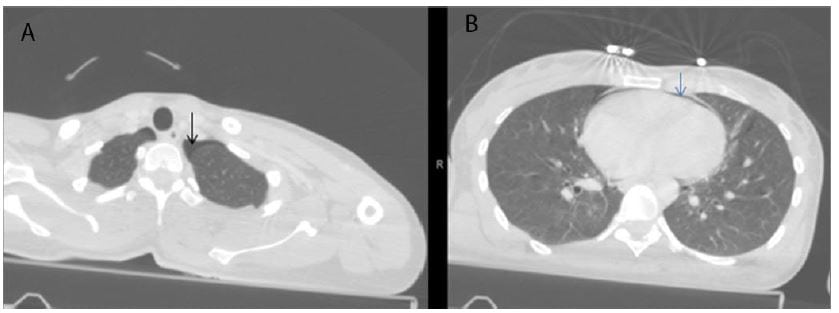

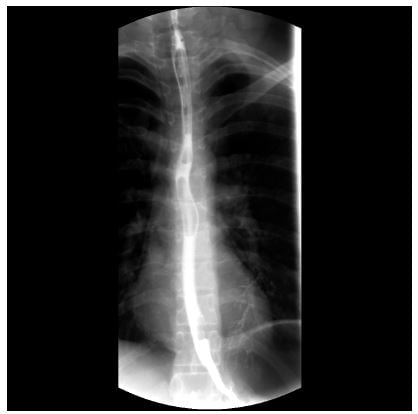

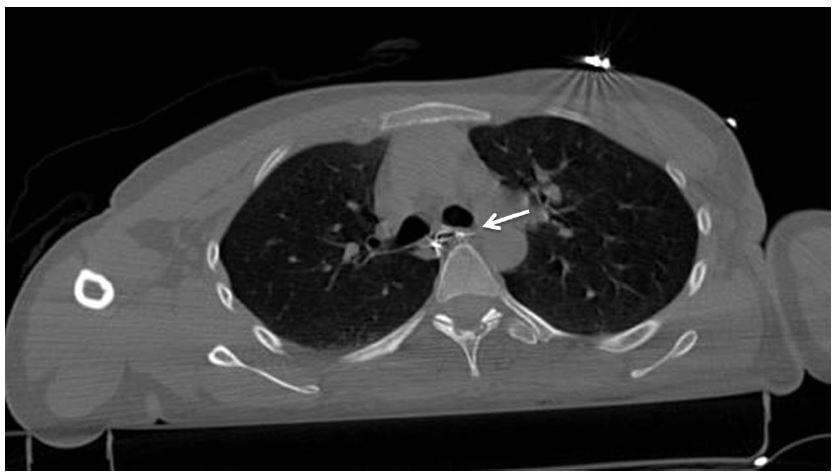

A 33-year-old woman was transported to the ED by ambulance after having jumped from the second story of a building in a suicide attempt. She was conscious on arrival. Patient evaluation revealed the following: Glasgow Coma Scale, E4M6V4; blood pressure, 104/65 mmHg; heart rate, 124 beats/min; breathing, 28 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 99%. Bilateral periorbital ecchymosis, superficial skin lesions approximately 2 and 3 cm in size in the right frontal area, and pain/tenderness above the left zygoma and the left clavicle were present. There was no shortness of breath or chest pain. The only pain was present in the left paravertebral region at the T3-4 level, and there were no other lesions on her back. Minimal tenderness was present on abdominal examination. Other physical examinations were normal. Bedside ultrasound (FAST) revealed no intra-abdominal or pericardial fluid, although left kidney contusion was suspected. Bedside chest radiograph revealed suspected pneumomediastinum. Hemoglobin level was 13.6 g/dL, and hematocrit level was 39.6%. Intravenous contrast enhancement for thoracoabdominal spiral computed tomography (CT) was performed and revealed bilateral minimal pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium, left kidney contusion, left transverse process fractures in the L3-4 vertebra, and non-displaced fracture at the left clavicle. A cortical contusion in the left frontal lobe and fractures in the superior aspect of the right lateral orbit, at the level of the frontotemporal junction on the right and in the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus, were determined on cerebral and maxillofacial CT. A left transverse process fracture was present in the T1 vertebra on cervical CT. Bedside echocardiography detected ejection fraction, and valves were normal; there was no pericardial effusion. Endoscopy was initially planned to exclude esophageal rupture, but alternative tests were then considered due to difficulties positioning the patient. Due to multiple fractures, the standing position required for contrast esophagography was not possible, and the patient was examined in the supine position. The patient ingested non-ionic contrast material in a supine position, and thoracic CT was performed at the time of swallowing. Contrast material extralumination from the esophagus was observed, and esophageal rupture was diagnosed. The patient was admitted to the general surgery department. Conservative treatment for esophageal perforation was performed with a nasogastric tube and intravenous antibiotherapy (ampicillin sulbactam 4×1.5 g and metronidazole 3×500 mg). Endoscopy revealed a probable area of perforation in the posterior hypopharynx. Esophagography with intense contrast material was performed in the anterior and lateral planes. No evidence of contrast leakage or compromised esophageal wall integrity was detected. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed no perforation at the tracheal or bronchial levels. No additional symptoms were encountered throughout observation, and the patient left the hospital of her own volition on the fifth day.

Figure 2

Thoracic computed tomography with oral contrast enhancement showing extraluminal contrast material from the esophagus.

DISCUSSION

Esophageal perforation is one of the most frequent causes of thoracic trauma-related mediastinitis. Iatrogenic causes are the most common in the etiology.3,4 The mechanism involved in blunt trauma-related esophageal rupture is unclear. The most common theory is that, as in Boerhaave syndrome, perforation occurs in the weakest area of the esophagus.5 Perforation can also occur when the esophagus is trapped between the sternum and thoracic vertebrae in association with fracture or compression of the thoracic vertebrae.6 Only a T1 transverse process fracture was present in the current case, and the region of the esophagus with contrast leakage was inferior to the carina. Therefore, the probable mechanism was thought to involve a rise in intraluminal pressure.

The most frequently observed symptoms in esophageal perforation are dysphagia, odynophagia, chest pain, and shortness of breath. No specific physical symptoms are associated with the early period. The most commonly observed finding is subcutaneous emphysema.4 In the current patient, the single finding present was back pain in the left paravertebral area. The absence of any skin lesion, deformity, or crepitation that might have accounted for pain in that region led to suspicion of esophageal perforation. When possible causes of the minimal pneumothorax, pneumopericardium, and pneumomediastinum observed on thoracic CT were investigated, the sternum and scapula were healthy, while stable bone fractures were present in the transverse processes in the clavicle and vertebra. No pulmonary contusion or bronchopulmonary lesion was seen. All of these negative findings caused suspicion, and the patient was evaluated for esophageal perforation in the early period. Esophageal perforation might have been easily overlooked had even one of these injuries been present in the patient.

Review of the literature revealed that esophageal perforations are frequently diagnosed late and that the associated mortality is high.2,7 Early diagnosis reduces mortality. However, suspicion is first necessary for early diagnosis. When esophageal rupture is suspected, diagnosis is often determined with contrast esophagography, chest radiograph, thoracic CT, or upper gastrointestinal system endoscopy. Imaging with Gastrografin is recommended in stable patients and has a false negativity rate of 36%.1,8 However, since multi-trauma patients are monitored on a trauma board and in a supine position in the early period, contrast esophagography, which must be performed while standing, is often not possible. Because chest radiograph has high sensitivity but low specificity for esophageal rupture, its contribution to diagnosis is limited. Upper gastrointestinal system endoscopy is often not an option in the ED. In addition, the endoscopy procedure is contraindicated in patients with cervical injury and wearing a neck brace, and the procedure is technically difficult. There was no direct evidence of esophageal perforation on the first contrast thoracic CT. Endoscopy could not be performed at the beginning both for technical reasons and because our multi-trauma patient could not stand. The patient ingested non-ionic contrast material, and CT imaging was performed at the time of swallowing. Contrast leakage was observed and esophageal perforation was diagnosed.

Successful treatment of esophageal perforations depends on the size of the rupture, time to diagnosis, and underlying diseases.1,9 Patients must be started on wide spectrum antibiotics. Primary surgery has been recommended as the gold standard in the past, although conservative treatment has been recommended for select patients in recent years.1,3 The present patient was stable and monitored conservatively since she was diagnosed in the early period.

CONCLUSION

Esophageal perforation should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting to the ED with pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium, or pneumothorax. If multiple trauma is present and neither contrast esophagography nor upper gastrointestinal system endoscopy can be performed, then performing thoracic CT with non-ionic contrast material may be a good diagnostic alternative.

Footnotes

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Nese Colak Oray, MD, Email: nese.oray@deu.edu.tr 9 / 2014; 15:659 – 662

Submission history: Revision received December 26, 2013; Submitted May 19, 2014; Accepted May 21, 2014

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1 Kuppusamy MK, Hubka M, Felisky CD Evolving management strategies in esophageal perforation: surgeons using nonoperative techniques to improve outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2011; 213:164-71

2 Brinster CJ, Singhal S, Lee L Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004; 77:1475-83

3 Eroglu A, Turkyilmaz A, Aydin Y Current management of esophageal perforation: 20 years experience. Dis Esophagus. 2009; 22:374-80

4 Søreide JA, Viste A Esophageal perforation: diagnostic work-up and clinical decision-making in the first 24 hours. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2011; 19:66

5 Blencowe NS, Strong S, Hollowood AD Spontaneous oesophageal rupture. BMJ. 2013; 346:f3095

6 Strauss DC, Tandon R, Mason RC Distal thoracic oesophageal perforation secondary to blunt trauma: case report. World J Emerg Surg. 2007; 2:8

7 Shaker H, Elsayed H, Whittle I The influence of the ‘golden 24-h rule’ on the prognosis of oesophageal perforation in the modern era. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010; 38:216-22

8 Hermansson M, Johansson J, Gudbjartsson T Esophageal perforation in South of Sweden: results of surgical treatment in 125 consecutive patients. BMC Surg. 2010; 10:31

9 Wu JT, Mattox KL, Wall MJ Esophageal perforations: new perspectives and treatment paradigms. J Trauma. 2007; 63:1173-84