| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Daniel Miller, MD, FACEP | University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Department of Emergency Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa |

ABSTRACT

Emergency physicians are often required to evaluate and treat undifferentiated patients suffering acute hemodynamic compromise (AHC). It is helpful to apply a structured approach based on a differential diagnosis including all causes of AHC that can be identified and treated during a primary assessment. Tension pneumoperitoneum (TP) is an uncommon condition with the potential to be rapidly fatal. It is amenable to prompt diagnosis and stabilization in the emergency department. We present a case of a 16-year-old boy with TP to demonstrate how TP should be incorporated into a differential diagnosis when evaluating an undifferentiated patient with AHC.

CASE

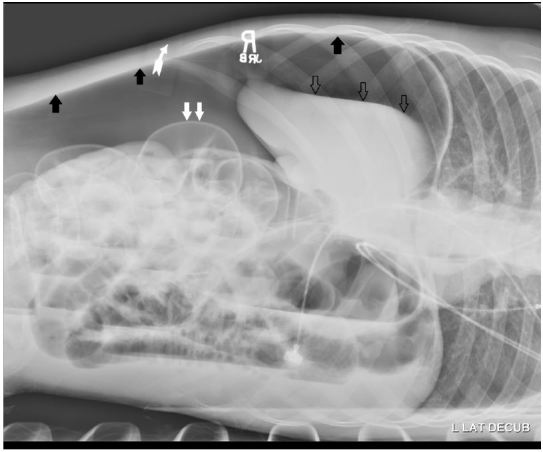

A 16-year-old Hispanic male presented to our emergency department (ED) with difficulty breathing that his mother first noted on the previous night. He had a history of muscular dystrophy (MD), frequent seizures and severe developmental delay causing him to be non-verbal at baseline. He also had a long-standing history of constipation. His mother had not noted any new symptoms until the previous night when he appeared to develop difficulty breathing. Upon arrival to the ED he was found to be in respiratory distress. His vital signs were significant for the following: heart rate 144 beats/minute; blood pressure of 43/22mmHg; temperature of 35.2ºC; and respiratory rate of 44 breaths/minute. Pulse oximetry waveform was initially undetectable. On initial exam we noted markedly but symmetrically diminished lung aeration, a tensely distended abdomen and mottled skin with cyanosis. When we attempted supplemental ventilation with bag valve mask we noted high airway pressures. Concurrent with obtaining intravenous access and placing the patient on continuous monitoring, we obtained portable supine chest (Figure 1) and left lateral decubitus abdominal (Figure 2) radiographs.

After noting massive pneumoperitoneum and elevation of the diaphragm we suspected tension pneumoperitoneum (TP) as the cause of shock. We positioned the patient in the right lateral decubitus position and placed three 14-gauge needles through the left abdominal wall, just lateral to the rectus musculature, and we advanced each needle until a rush of air was heard. As air was evacuated the patient’s abdominal distension visibly resolved. We soon noted decreased airway resistance and improved aeration. Within minutes the patient’s blood pressure improved to 93/47mmHg, and his pulse oximetry waveform became detectable at 93%. A repeat chest radiograph showed markedly improved pneumoperitoneum and diaphragmatic excursion with persistently dilated loops of bowel (Figure 3).

The patient was then taken to the operating room where he was found to have purulent peritonitis, and a 1.5cm cecal perforation was identified and repaired. A large rectal scybalum was also noted, and as there was no other bowel pathology identified during laparotomy, the cause of our patient’s bowel perforation was determined to be obstipation. We suspect that his preexisting communication difficulties caused a delay in presentation, allowing his constipation to progress to bowel perforation.

DISCUSSION

Pneumoperitoneum is a radiographic term defined as free air within the peritoneal cavity. This finding usually suggests a perforated viscous, but up to 15% of cases occur in the absence of perforation.1 Pneumoperitoneum can occur post-procedurally or from passage of air from thoracic, abdominal, gynecologic or idiopathic sources (Table). Post-procedural pneumoperitoneum can follow percutaneous tube placement, laparotomy, laparoscopy and endoscopy. After laparoscopy air is expected to be visible on imaging for one week but may last up to four weeks.2 Approximately 0.1% of endoscopic procedures will result in pneumoperitoneum.3 The majority of these cases are the result of microperforation and do not result in peritonitis. In thoracic sources high intrathoracic pressure leads to introduction of air into the peritoneum via either diaphragmatic defects or perivascular connective tissue, allowing the mediastinum to communicate with the peritoneum. Pneumoperitoneum from abdominal sources occur through perforation of a hollow viscous, gas-forming bacterial infection (abscess or peritonitis) or rupture of gas-filled cysts within the alimentary tract wall (pneumatosis cystoides). Gynecologic sources of pneumoperitoneum are a result of the anatomic communication between the fallopian tubes and the peritoneal cavity and can occur under any circumstances that cause the pressure of air within the gynecologic organs to exceed the intraabdominal pressure (IAP) (mean IAP is between 16 and 20mmHg with a maximum of 25.5mmHg in non-pathologic states).4 The rate of pneumoperitoneum caused by processes that do not require surgical intervention has been estimated at 10%, so it is helpful to divide pneumoperitoneum into surgical and non-surgical categories.5 A method has been proposed to identify cases of pneumoperitoneum that do not require surgical intervention. If all of the following criteria are met it may be reasonable to consider non-surgical management: pneumoperitoneum is identified incidentally, there is a benign alternative explanation for the presence of air, there is no free fluid in the abdomen, and there are no signs of peritonitis or sepsis.6 While this method has not been prospectively validated, it is reasonable to consider managing with advanced imaging and serial examinations in these potentially non-surgical cases.

| Category | Cause |

|---|---|

| Abdominal | Anastomotic leak |

| Collagen vascular diseases | |

| Diverticulosis (jejunal or sigmoid) | |

| Perforation of hollow viscus | |

| Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis | |

| Rupture of intra-abdominal abscess | |

| Gynecologic | Coitus |

| Knee-chest exercise | |

| Pelvic inflammatory diseases | |

| Post-partum exercise | |

| Vaginal insufflation | |

| Vaginal douching | |

| Thoracic | Adenotonsillectomy |

| Asthma | |

| Barotrauma/thoracic trauma | |

| Bleb rupture (spontaneous) | |

| Bronchopulmonary fistula | |

| Bronchoscopy | |

| Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (can occur from blunt trauma, positive pressure ventilation or both) | |

| Pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum | |

| Positive end-expiratory pressure ventilation | |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | |

| Severe coughing | |

| Post-procedural | Laparoscopy/laparotomy |

| Endoscopy | |

| Gynecologic examination procedures | |

| Postpolypectomy syndrome | |

| Percutaneous enteric tube placement/displacement | |

| Peritoneal dialysis | |

| Other | Gas forming bacterial infection |

| Idiopathic |

TP is an extreme form of pneumoperitoneum that occurs when intraabdominal free air reaches pressures high enough to impede venous return to the heart and to inhibit diaphragmatic excursion. Diminished venous return leads to decreased diastolic filling thereby decreasing cardiac output. This manifests as hypotension and decreased systemic perfusion. Inhibition of diaphragmatic excursion decreases tidal volume. If the patient is unable to compensate with an increased respiratory rate this will result in decreased minute ventilation and manifest as hypercarbic respiratory distress. If not diagnosed and treated promptly, TP will rapidly lead to death.

TP was first described in the medical literature by Oberst in 1917 when a grenade explosion resulted in gastric perforation.7 TP has since been reported as a complication of bowel perforation secondary to endoscopy, peptic ulcer disease and bowel obstruction.8-12 It is theorized that TP results from viscous perforation when overlying omental fat acts as a one-way valve, allowing gas to reach high pressures in the peritoneal cavity. It appears that barotrauma-induced TP without any viscous perforation is particularly rare, but this has also been reported.13 Of particular interest to emergency physicians are cases of TP following positive pressure ventilation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation with associated gastric rupture.14,15 Because the air is extraluminal, a gastric tube will not improve ventilation in these cases. Upon our review of the literature, we were unable to identify any previously reported cases of TP caused by constipation. We suspect that our patient’s history of MD, combined with his non-mobile and non-verbal status resulted in this novel presentation of TP. MD is known to be associated with increased colonic transit times, resulting not only from direct damage to smooth muscle, but also due to immobility and weak abdominal musculature contributing to constipation.16,17 Additionally, our patient was non-verbal. His inability to communicate his symptoms allowed his condition to progress unnoticed until it resulted in spontaneous perforation of his colon, a condition more commonly described in elderly patients with constipation.18 His non-verbal status further allowed this catastrophe to go unnoticed until it led to TP and its associated respiratory distress, the symptom that prompted his mother to bring him to the ED for evaluation.

The diagnosis of TP should be suspected in patients who present with respiratory distress associated with abdominal distension. Physical exam findings reveal high airway pressures, a tensely distended abdomen and poor systemic perfusion in TP. This diagnosis can be supported by chest and abdominal radiographs showing low lung volumes and a large amount of intraperitoneal free air. Sometimes the liver can also be observed to be inferiorly and medially displaced (the “saddle bag” sign). Initial treatment of TP consists of percutaneous needle decompression. The vast majority of reported cases of TP are associated with a perforated viscous. These patients should be emergently transferred to the operating room for diagnostic and therapeutic laparotomy unless there is highly compelling evidence to suggest that no such perforation has occurred.

CONCLUSION

TP should be included in the differential diagnosis when assessing undifferentiated patients presenting to the ED with acute hemodynamic compromise. These patients present with hypotension, respiratory distress, a tensely distended abdomen and high inspiratory pressures. The diagnosis of TP can be supported by portable radiographs, and it can be confirmed with diagnostic and therapeutic needle decompression of the abdomen.

Footnotes

Section Editor: Rick A. McPheeters, DO

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Daniel Miller, MD, FACEP, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, 200 Hawkins Drive, 1008 RCP, Iowa City, IA 52242. Email: Daniel-miller@uiowa.edu. 9 / 2015; 16:777 – 780

Submission history: Revision received December 23, 2014; Submitted May 13, 2015; Accepted June 3, 2015

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Roh JJ, Thompson JS, Harned RK, et al. Value of pneumoperitoneum in the diagnosis of visceral perforation. Am J Surg. 1983;146(6):830-3.

2. Gayer G, Jonas T, Apter S, et al. Postoperative pneumoperitoneum as detected by CT: prevalence, duration, and relevant factors affecting its possible significance. Abdom Imaging. 2000;25:301-5.

3. Mularski RA, Ciccolo ML, Rappaport WD. Nonsurgical causes of pneumoperitoneum. West J Med. 1999;170:41-6.

4. Cobb WS, Burns JM, Kercher KW, et al. Normal Intraabdominal Pressure in Healthy Adults. J Surg Res. 2005;129(2):231-235.

5. Cecka F, Sotona O, Subrt Z. How to distinguish between surgical and non-surgical pneumoperitoneum?. Signa Vitae. 2014;9:1.

6. Oberst A. Das Spannungspneumoperitonaion. Zentralbl f Chir. 1917;44:354-355.

7. Kim SJ, Ahn SI, Hong KC, et al. Pneumatic colonic rupture accompanied by tension pneumoperitoneum. Yonsei Med J. 2000;41(4):533-535.

8. Kealey WD, McCallion WA, Boston VE. Tension pneumoperitoneum: a potentially life-threatening complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrojejunostomy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1996;22(3):334-335.

9. Ortega-Carnicer J, Ruiz-Lorenzo F, Ceres F. Tension pneumoperitoneum due to gastric perforation. Resuscitation. 2002;54(2):215-216.

10. Hector A. Pneumoperitoneum under tension in peritonitis due to digestive tract perforation (apropos of 15 cases). Actual Hepatogastroenterol. 1968;4(4):153-163.

11. Devine JF, McCarter TG. Tension Pneumoperitoneum, Images In Clinical Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1985.

12. Canivet JL, Yans T, Piret S, et al. Barotrauma-induced tension pneumoperitoneum. Acta Anaesth Belg. 2003;54:233-236.

13. Mills SA, Paulson D, Scott SM, et al. Tension pneumoperitoneum and gastric rupture following cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Ann Emerg Med. 1983;12(2):94-5.

14. Cameron PA, Rosengarten PL, Johnson WR, et al. Tension pneumoperitoneum after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Med J Aust. 1991;155(1):44-7.

15. Perkin GD, Murray-Lyon I. Neurology and the gastrointestinal system. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:291-300.

16. Gottrand F, Guillonneau I, Carpentier A. Segmental colonic transit time in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66(10):1262.

17. Yang B, Huai-Kun N. Diagnosis and treatment of spontaneous colonic perforation: Analysis of 10 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(28):4569-4572.