| Author | Affiliation |

| Justin Yax, DO, DMTH | Case Western Reserve University, University Hospitals/Case Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio |

| David Cheng, MD, DMTH | Case Western Reserve University, University Hospitals/Case Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio |

Introduction

Case Presentation

ABSTRACT

Osteomyelitis pubis is an infectious inflammation of the symphysis pubis and accounts for 2% of hematogenous osteomyelitis. This differs from osteitis pubis, a non-infectious inflammation of the pubic symphysis, generally caused by shear forces in young athletes. Both conditions present with similar symptoms and are usually differentiated on the basis of biopsy and/or culture. A case of osteomyelitis pubis is presented with a discussion of symphisis pubis anatomy, clinical and laboratory presentation, etiology and risk factors, and optimal imaging studies.

INTRODUCTION

Infection of the symphysis pubis, or osteomyelitis pubis, and non-infectious inflammation of the same joint, or osteitis pubis, are distinct entities that present similarly. The diagnosis of osteomyelitis pubis is often missed or delayed due to the infrequency of the disease and its variable presentation. Because many patients with this condition report sudden onset of pelvic pain, they are often seen in the emergency department (ED). The emergency physician can make a difference in the course of the disease by recognizing the condition early, and starting the patient on the road to definitive workup and treatment, which involves pain control and long-term intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 39-year-old woman with a history of genital herpes and normal vaginal delivery eight months ago presented with nine days of severe pelvic pain. Initially she experienced a spontaneous peri-vaginal “pressure sensation” that was five out of ten in intensity. She denied vesicles in her perineum or vulva, fever, or chills. Seven days prior to presentation, she developed a temperature to 100.3ºF and went to another hospital where a pelvic exam, pelvic ultrasound and a computed tomography (CT) of the pelvis with oral and IV contrast were performed. All tests were normal except for a leukocytosis of 14,000 cells/mcL. She was discharged with a diagnosis of leukocytosis of unclear etiology and discharged on hydrocodone/acetaminophen for pain control. On follow-up with an obstetrician a few days later, another pelvic exam was unremarkable and no vesicles were seen. She was started on valaciclovir for suspected herpes sine herpete, an atypical presentation of genital herpes without obvious lesions.

Three days prior to presentation, our patient had increasing difficulty walking secondary to her pain. She presented to another hospital where a repeat CT of the pelvis was negative. She was discharged on oxycodone/acetaminophen and ibuprofen and was to follow up with her obstetrics pelvic floor specialist. Prior to her follow-up appointment, however, her pain was so great she presented to our institution unable to ambulate without a walker and now had pain that radiated into her right buttock.

At presentation, she denied loss of bowel or bladder function, but had soiled herself due to her difficulty reaching the bathroom and her limited mobility. She denied trauma. She was febrile to 101.3ºF and the remainder of her vital signs were normal. Her exam revealed severe suprapubic tenderness and her lower extremity exam revealed severe pain with hip flexion bilaterally and normal bilateral patellar and Achilles reflexes. Saddle hyperestheia was noted and otherwise sensation was normal. Rectal tone was normal and examination of her back showed no spinal step-offs or lesions. She was exquisitely tender over the right gluteus region. Her white blood cell count was 12,600 cells/mcL, C-reactive protein (CRP) was 37.1mg/L, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 114mm/hr. The laboratory abnormalities caused the treating physicians to order a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis, which was consistent with osteomyelitis pubis. She was admitted for pain control and further workup. Blood cultures drawn on admission grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, and the patient was discharged on four weeks of IV ceftriaxone and gradually improved.

DISCUSSION

The pubic symphysis is classified as an amphiarthrodial (slightly movable) joint and shares this classification with the intervertebral disks of vertebral bodies, the distal tibiofibular articulation, and sacroiliac joint articulation with pelvic bones.5,6 The pubic symphysis consists of an intrapubic fibrocartilage disk sandwiched between thin layers of hyaline cartilage.5 The hip adductors originate inferiorly on the pubic symphysis and the pectineus, rectus, and the inguinal ligament insert superiorly while muscles of the pelvic floor insert posteriorly, helping to explain the extensive distribution of pain throughout the pelvis in our patient.

Osteitis pubis, a non-infectious inflammation of the pubic symphysis, is caused by shear stresses to the joint and is not an infectious process. Athletes are more predisposed to this condition given the insertion and origin of several muscle groups on the pubic rami. In particular, athletes in sports involving twisting and cutting motions such as rugby, American football, soccer, ice hockey, tennis, basketball and endurance running are at higher risk.7-9 One study showed that 76% of players on an English professional soccer team had symphyseal abnormalities on pelvic radiographs, suggestive of repetitive stress injury.10 This is thought to be due to shear forces transmitted along hip adductors by repetitive kicking.11 Younger patients are thought to be at higher risk for hematogenous bacterial seeding of a sterile, inflamed amphiarthrosis given their ligamentous laxity. In older patients, these joints become sclerosed and ossified, probably reducing the risk of bacterial seeding.12-14 Therefore, theoretically, in young patients osteitis pubis may become hematogenously seeded by bacteria, creating osteomyelitis pubis.

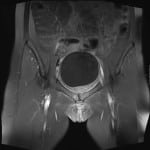

Figure. Axial T2 weighted image of the pelvis with fat saturation reveals bone marrow edema (white) on the right ischial spine just adjacent to the symphysis pubis suggesting osteomyelitis. Blood cultures grew Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus and patient was treated with a prolonged course of intravenous ceftriaxone by the inpatient infectious disease team and improved.

Osteomyelitis pubis by definition is infectious in nature and its clinical and laboratory manifestations can vary. In a study of 100 patients with laboratory-confirmed osteomyelitis pubis, only 74% had fever, 59% had painful gait and 45% had pain with hip motion.15 Laboratory values were not always abnormal, as in the same study leukocytosis was observed in only 35% of patients. ESR and CRP may be abnormal but are nonspecific. Bacteremia, not a useful marker in the ED, was present in 73% of patients with blood culture results reported. Cultures of needle aspirates of the symphysis pubis were more sensitive with 86% positive. Finally, in 89% of cases requiring surgical debridement, surgical specimens were the only positive culture result.14

Emergency physicians need to be aware of the risk factors that predispose to osteomyelitis pubis. The major risk factors in this study were female incontinence surgery (24%), being an athlete (19%), history of pelvic malignancies (17%), and IV drug use (15%). The remainder of the risk factors included vaginal delivery, male incontinence surgery, cardiac catheterization, and herniorraphy. Ten percent of the patients in the study had no identifiable risk factors.15 Staphylococcus aureus was the most common etiologic agent in athletes, whereas polymicrobial infection and enteric pathogens were most often responsible in patients with pelvic malignancies. Pseudomonas aeruginosa was a common etiology in intravenous drug users prior to 1983, but its incidence is decreasing.2

Our patient underwent CT of the pelvis twice at outside facilities and plane radiographs once prior to an MRI finally revealing her diagnosis (Figure). Studies have shown that MRI is 100% sensitive for detecting cases of osteomyelitis pubis, but are not readily available at all institutions.15 CT is another option, but false negative rates as high as 10% have been reported in the literature15 and this should be considered if clinical suspicion is high despite a negative CT of the pelvis. These patients should be admitted for further workup or referred urgently for MRI if the diagnosis is still suspected.

Osteomyelitis pubis should be added to the emergency physician’s differential diagnosis for acute onset pelvic pain of unclear etiology, and MRI may be needed for definitive diagnosis. Despite the complicated workup and treatment of this disease, the emergency physician can make a significant difference in the timely diagnosis and early treatment in these patients if the diagnosis is considered in patients presenting with severe pelvic pain.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Joel Schofer, MD, MBA

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Justin Yax, DO, DMTH, 11100 Euclid Ave, Wearn B-17, Cleveland, OH 44106. Email: Justin.Yax@uhhospitals.org.

Submission history: Submitted July 27, 2014; Revision received August 19, 2014; Accepted August 20, 2014

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

- McHenry MC, Alfidi RJ, Wilde AH, et al. Hematogenous osteomyelitis; a changing disease. Clev Clinic Q. 1975;42:125-53. [PubMed]

- Baum C, Hsu JP, Nelson RC. The impact of the addition of naloxone on the use and abuse of Pentazocine. Public Health Rep. 1987;102:426-429. [PubMed]

- Bouza E, Winston DJ, Hewitt WL. Infectious osteitis pubis. Urology. 1978;12:663-9. [PubMed]

- Lupovitch A, Elie JC, Wysocki R. Diagnosis of acute bacterial osteomyelitis of the pubis by means of fine needle aspiration. Acta Cytol. 1989;33:649-51. [PubMed]

- Gamble JG, Simmons SC, Freedman M. The symphysis pubis. Anatomic and pathologic considerations. Clin Orthop. 1986;203:261-72. [PubMed]

- Goldring SR, Goldring MB. Firestein: Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology, 8th ed., Structure and function of Bone, Joints and Connective Tissue. 2008.

- Batt ME, McShane JM, Dillingham MF. Osteitis pubis in collegiate football players. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:629-633. [PubMed]

- Koch RA, Jackson DW. Pubic symphysitis in runners: A report of two cases. Am J Sports Med. 1981;9:62-63. [PubMed]

- Pauli S, Willemsen P, Declerck K, et al. Osteomyelitis pubis versus osteitis pubis: A case presentation and review of the literature. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36:71-73. [PubMed]

- Harris NH, Murray RO. Lesions of the pubic symphysis in athletes. Br Med J. 1974;4:211-214. [PubMed]

- Hanson PG, Angevine M, Juhl JH. Osteitis pubis in sport activities. Phys Sportsmed. 1978;6:111-114.

- Baker ME, Martinez S, Kier R, et al. High resolution computed tomography of the cadaveric sternoclaviular joint: findings in degenerative joint disease. J Computed Tomogr. 1988;12:13-18. [PubMed]

- Shibata Y, Shirai Y, Miyamoto M. The aging process in the sacroiliac joint: Helical computed tomography analysis. J Orthop Sci. 2002;7:12-18. [PubMed]

- Snow CC. Equations for estimating age at death from the pubic symphysis. J Forensic Sci. 1983;28:864-870. [PubMed]

- Ross JJ, Hu LT. Septic arthritis of the pubic symphysis: a review of 100 cases. Medicine. 2003;82(5):s340-344. [PubMed]