| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Stefan Flores, MD | Highland Hospital-Alameda Health System, Department of Emergency Medicine, Oakland, California |

| Christine Riguzzi, MD | Highland Hospital-Alameda Health System, Department of Emergency Medicine, Oakland, California; Alta Bates Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Oakland, California |

| Andrew A. Herring, MD | Highland Hospital-Alameda Health System, Department of Emergency Medicine, Oakland, California; University of California, San Francisco, Department of Emergency Medicine, San Francisco, California |

| Arun Nagdev, MD | Highland Hospital-Alameda Health System, Department of Emergency Medicine, Oakland, California; University of California, San Francisco, Department of Emergency Medicine, San Francisco, California |

Case report

Discussion

Conclusion

ABSTRACT

Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks are becoming more essential for the management of acute pain in the emergency department (ED). With increased block frequency comes unexpected complications that require prompt recognition and treatment. The superficial cervical plexus block (SCPB) has been recently described as a method for ED management of clavicle fracture pain. Horner’s syndrome (HS) is a rare and self-limiting complication of regional anesthesia in neck region such as brachial and cervical plexus blocks. Herein we describe the first reported case of a HS after an ultrasound-guided SCPB performed in the ED and discuss the complex anatomy of the neck that contributes to the occurrence of this complication. [West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(3):428–431.]

CASE REPORT

A 20-year-old male presented to the emergency department (ED) with right shoulder pain and deformity after falling from his bicycle. Exam was notable for swelling and tenderness overlying the right clavicle with a comminuted mildly displaced clavicular fracture confirmed by plain radiography. The patient complained of severe pain unrelieved by initial parenteral opioids. For improved pain management, an ultrasound-guided superficial cervical plexus block (SCPB) was performed.1,2

Ultrasound-guided SCPB

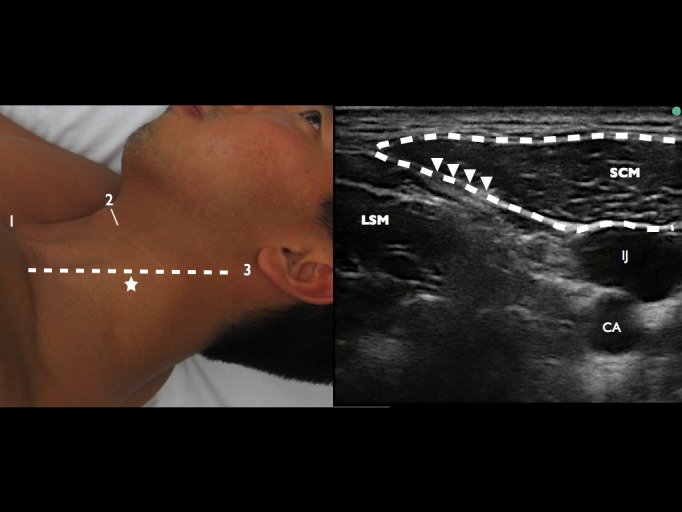

The patient was placed on continuous cardiac monitoring. Placement of a high frequency linear transducer (13-6 MHz, SonoSite™ M-Turbo, Bothell, WA) was approximated by palpation of the superior pole of the thyroid cartilage (C4 level), and visual approximation of the midpoint of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM), from mastoid to the clavicle.

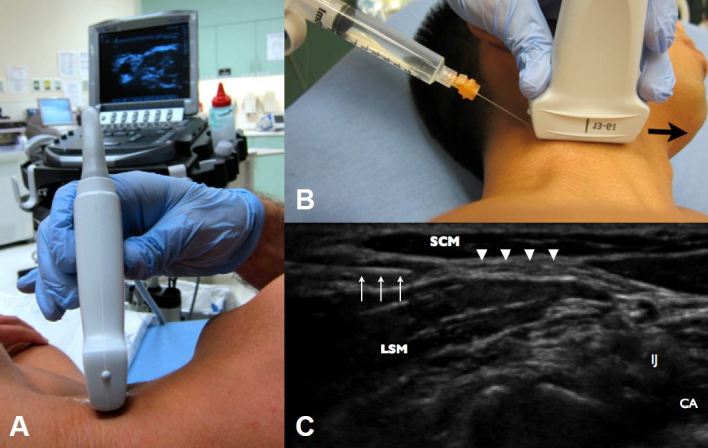

The superficial cervical plexus was identified as the hyper echoic fascia posterior to the SCM and superficial to the levator scapula muscle (LSM) (Figure 1). The area was prepped with chlorehexidine and a skin wheal of 1% lidocaine was injected. The patient was placed in left lateral decubitus with the ultrasound system contralateral to the provider (Figure 2). Using a 25g 1.5-inch standard hypodermic needle, with an in-plane posterior approach, 10mL of 0.5% bupivacaine was injected under the SCM in the fascial space between the SCM and LSM. Aspiration and real-time visualization of anechoic anesthetic was done to prevent intravenous injection (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A, Probe positioning for the in-plane approach in the lateral decubitus position. B, Needle injection and proper orientation of probe marker during superficial cervical plexus block. The arrow delineates the probe marker orientation. C, Ultrasound image of needle injection within the superficial cervical plexus. The arrows mark the needle. The sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) noted on the top right, the levator scapulae muscle on top left (LSM), the carotid artery (CA) and internal jugular vein (IJ) on the bottom right, and the injection site marked (arrowheads).

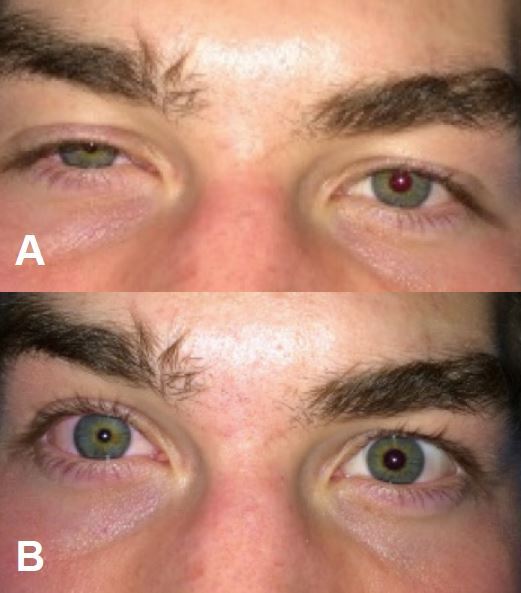

Approximately 15 minutes after block placement, the patient had complete pain relief, reporting sensory deficit in the cape region of the shoulder, neck, and skin overlying the clavicle without changes in motor function of the arm. Forty-five minutes later, the patient complained of right-sided facial numbness and was noted to have ptosis, miosis, and conjunctival injection on the ipsilateral side of the block (Figure 3). There was no voice hoarseness, anhidrosis or enophthalmos. The patient was observed in the ED and symptoms resolved 1.5 hours after the block was placed.

DISCUSSION

Potential complications of a SCPB include Horner’s Syndrome (HS), partial brachial plexus blocks, phrenic and recurrent laryngeal nerve blocks. We believe the HS described here developed as an inadvertent complication of deep spread of local anesthetic after superficial injection, involving the ipsilateral cervical sympathetic chain.3 Several studies suggest that the deeper compartments of the neck, (containing the cervical sympathetic chain), and superficial spaces are in communication with each another allowing for potential deep spread of a superficial injection.4-6

Nash et al.7 reported that the investing layer of the deep cervical fascia in the anterior triangle of the neck is nearly non-existent, suggesting that fat and connective tissues surrounding neck neurovascular structures provide direct communication between the subcutaneous tissue and the prevertebral layer beneath the deep cervical fascia. Pandit et al.4 further demonstrated that dye injected above the prevertebral layer of the deep cervical fascia penetrates through pores where the nerves pierce the fascia, ending in the deep cervical space. While the precise anatomy has not been completely elucidated, current data supports the concept that the deeper neck compartments potentially communicate directly with the subcutaneous tissue, which explains why in our case the patient experienced a ipsilateral HS after a SCPB. We hypothesize that adhering to three simple precautions can reduce the incidence of HS. More than 5mLs of local anesthetic volume is unnecessary, and placing larger volumes may promote deeper spread of local anesthetic via the anatomic pathways described above. Needle placement at the superior pole of the thyroid (C4 level) should be ensured and not approximated, as was done in this case. Finally, proper depth of injection should be ensured. Needle-tip placement should be maintained just underneath the SCM belly; insertion past the superficial investing fascia may promote the anesthetic to spread into the deep cervical fascial plane potentially involving the phrenic nerve, brachial plexus, and the stellate ganglion.5

Finally, it is important to be aware that if HS occurs after the SCPB, providers should consider it self-limiting, requiring only patient reassurance and observation versus urgent neuroimaging to evaluate for an acute stroke.

CONCLUSION

The SCPB is strategy for ED pain management of clavicle fractures. However, emergency clinicians should be aware that similar complications expected of a deep cervical plexus block could occur with the SCPB, such as HS. To minimize risk of complications of the SCPB, in addition to standard precautions for ultrasound-guided nerve blocks, several precautions should be taken. Clinicians should be aware of the anatomy of the superficial cervical plexus and be familiar with the landmarks, ensuring to stay at the level of C4; the injection should be shallow, just under the SCM belly; and appropriate anesthetic volumes (2–5mL) should be used. The development of HS after SCPB can be frightening to patients and the physician should reassure the patient that it is self-limited and not a sign of intracranial pathology or permanent damage.

Footnotes

Section Editor: David T. Williams, MD

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for Correspondence: Stefan Flores, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, Highland Hospital-Alameda Health System, 1411 E. 31st St., Oakland, CA 94602-1018. Email: Stefanos.flores@gmail.com. 5 / 2015; 16:428 – 431

Submission history: Revision received January 4, 2015; Submitted January 18, 2015; Accepted February 25, 2015

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

Needle injection within the superficial cervical plexus.

REFERENCES

1. Herring AA, Stone MB, Frenkel O, et al. The ultrasound-guided superficial cervical plexus block for anesthesia and analgesia in emergency care settings. AM J Emerg Med. 2012;30:1263-7.

2. Tran de QH, Tiyaprasertkul W, Gonzalez AP. Analgesia for clavicular fracture and surgery: a call for evidence. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2013;38:539-43.

3. Alzahrani T, Alnajjar M, Algarni AD, et al. Delayed Horner’s syndrome following ultrasound-guided interscalene brachial plexus block. Saudi J Anaesth. 2014;8:121-3.

4. Pandit JJ, Dutta D, Morris JF. Spread of injectate with superficial cervical plexus block in humans: an anatomical study. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91:733-5.

5. Pandit JJ, Satya-Krishna R, Gration P. Superficial or deep cervical plexus block for carotid endarterectomy: a systematic review of complications. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:159-69.

6. Pintaric TS, Hocevar M, Jereb S, et al. A prospective, randomized comparison between combined (deep and superficial) and superficial cervical plexus block with levobupivacaine for minimally invasive parathyroidectomy. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2007;105:1160-3.

7. Nash L, Nicholson HD, Zhang M. Does the investing layer of the deep cervical fascia exist?. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:962-8.