| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Vinodinee L. Dissanayake, MD | John H Stroger, Jr. Hospital of Cook County, Department of Emergency Medicine, Chicago, Illinois |

| Isam Nasr, MD | John H Stroger, Jr. Hospital of Cook County, Department of Emergency Medicine, Chicago, Illinois |

Introduction

Case report

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

ABSTRACT

Social networking sites (SNS), the modern mainstay of adolescent expression, may provide vital information to physicians. The emergency department (ED) is a setting where SNS may be helpful. A reticent 19-year-old in the ED prompted a search for pertinent information on the Internet, where a profile on www.myspace.com relayed a troubled post. The patient was admitted for psychiatric evaluation due to intentional overdose. These SNS may provide a venue for physicians to learn about risky behaviors and life stressors that would help identify underlying medical issues in young adults. We provide a guideline on how to utilize SNS with privacy rights in mind.

INTRODUCTION

Social networking sites (SNS) are popular among adolescents. Teens use SNS for a variety of reasons, such as to weblog (blog), to find and maintain relationships, to be entertained, to locate information, and to secure an emotional outlet.1–7 According to a national survey, 87% of adolescents aged 12–17 confirmed Internet use, and about 51% admitted to daily use.1 MySpace, a once-popular SNS, contains 200 million web profiles, and a quarter of these are owned by minors.2 Online interaction has been reported to be a safe and effective means for adolescents to mature; it is a place where they learn self-control, find it easier to express feelings, and see varying viewpoints.1,8 Studies and anecdotal experience have found that online profiles often reveal personal details regarding relationships, health risk behaviors such as substance abuse and sexual practices, and mental health issues such as depression.9,10 When adolescents post this information publicly, concerns of safety arise as the information may be accessible to anyone, including cyber-bullies, sexual predators and criminals, especially if privacy concerns were not addressed at the time of opening the account.1,2

Physicians have more recently started to use these websites to interact with patients to provide information regarding disease and to keep in touch in a more effective manner.11 However, a previously unrecognized utility exists; there have been no reports of physicians employing this tool to obtain historical data when patients are not able to provide a history. The following case depicts a clinical scenario where visiting a MySpace public profile provided information regarding an uncommunicative patient’s mood and potential motives for drug intoxication. Concerns regarding patient privacy may deter the use of these profiles by health practitioners; however, these profiles are published on the web with the inferred permission of their owners.

CASE REPORT

A 19-year-old male was brought to the emergency department (ED) by the fire department after he was found wandering in the bus terminal, combative and agitated. He provided us with 2 different names and his city of origin but would not divulge any details such as family history, past medical or surgical history, current medications, social history or whether he had ingested any medications or taken any drugs prior to arrival. Among his belongings was an empty pill bottle labeled cyclobenzaprine, which had been prescribed to someone other than the name provided. He had 3 different identification cards in his possession, yet none of them had any photographs resembling him.

On examination, he was well-appearing, disoriented, agitated and mumbling anxiously. His heart rate was 130 beats per minute, blood pressure was 96/60 mmHg, temperature was 35.9°C (96.7°F), respiratory rate was 24 breaths per minute with an oxygen saturation of 96% on room air. His skin was flushed, warm and dry without obvious trauma or any other abnormalities. The pupils were mid-range and sluggish to light. Cardiac examination revealed tachycardia without murmurs, and the lung examination was clear to auscultation bilaterally. He had no abdominal tenderness. He displayed no focal neurologic deficits and moved all extremities spontaneously with 5/5 strength. Reflexes were +2/4 bilaterally. He was disoriented to place and time and after persistent requests to state his name, he gave the same name consistently as time progressed.

A chest radiograph showed clear lung fields, and an ECG showed sinus tachycardia without QRS widening or QT prolongation. The patient became increasingly anxious, attempting to leave the room and becoming more hostile with medical personnel even after multiple trials of reorientation, reassurance and calming techniques. He would not provide us with any family contacts for further information. He was restrained for his own safety. A basic metabolic panel, a complete blood count, acetaminophen and aspirin levels, and a urine drug screen were ordered.

As we were unable to determine his true identity, we used the names he had given us to search the Internet. Upon entering one of the names on www.myspace.com, an account that displayed a picture of our patient appeared. Positive identity was made after reviewing several photographs while matching his hometown to what was included as “location” on his profile. On his public profile, 3 days prior to presentation, he stated that he was “chillin in [a] motel room,” and his mood was “betrayed.” This enabled us to determine that he might have suffered a life stressor recently that eventually led to his visit to the ED that night.

DISCUSSION

SNS have been underused by the medical profession for historical data when faced with a difficult patient. These websites may represent a previously overlooked yet easily accessible domain that could provide meaningful information at a moment’s notice for recalcitrant adolescents and young adults in the ED suffering from emotional turmoil. These sites are often mired with privacy issues; however, those who set up these profiles determine how much information they would like to publish in their privacy settings. Thus, it may be argued that the information published in the public domain is viewed with the inferred permission of its owner.

The blog is an important service provided through SNS.3 Studies have shown that adolescents who live in households earning less than $50,000 per year and those who live with a single parent are more likely to blog on the Internet.12 Blogs have become more prevalent with the advent of frequently updated websites, such as Twitter, where a change in status is portrayed in reverse chronological order for others to see and make commentary. With regard to truthful disclosure, sufficient evidence has shown that bloggers tend to post accurate portrayals of themselves on their profiles.1

An important function blogging provides for users is an outlet to share emotions with a community and receive feedback.3 Prior to the advent of blogs, journals were used as a coping strategy, and multiple studies have shown that this remains an effective therapeutic tool, leading to a revitalization of the author’s physical, emotional, and psychological health, and improving social functioning.13–17 In 2006 a study found that 70% of blogs were considered personal journals where daily activities, thoughts and feelings were expressed. However, what was once a private diary is now open to public feedback, an attribute that is unique to the blog experience.3,7 The practice of blogging engages authors in cathartic venting of psychological frustration and effectively reduces distress through self-reflection and constructive feedback from the community.7 In addition, new bloggers may have signed up with SNS for the sole purpose of sharing with their community the life stressors they are facing.3,7

LIMITATIONS

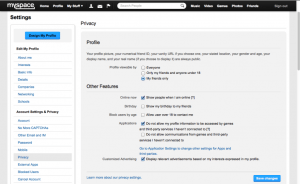

There are limitations in the use of the Internet as sources of information regarding patients. Although studies have found most blog entries to be quite truthful, some bloggers may embellish life events heavily or even lie about high-risk behaviors. However, such exaggerated claims on the Internet may serve as a platform for physicians to further educate our troubled teens and young adults about high-risk behaviors, regardless of how embellished they may be. Finally, the ethics of patient privacy is a concern. Those opening an SNS account must agree to a “Terms of Use Agreement and Privacy Policy.” The privacy policy at MySpace states that information posted on a profile, both “personally identifiable” and non-identifiable information, is posted at the sole discretion of the account-holder.18 Control of who is able to access and view this information is determined by the privacy settings of the account-holder.19 Figures 1 and 2 portray the privacy policy and demonstrates the available privacy options.

Figure 1. MySpace privacy policy.

Figure 2. Available privacy options in account settings.

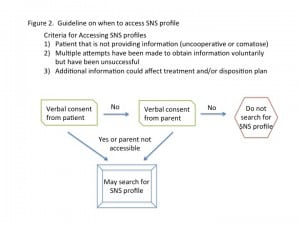

Even with implied consent from this policy, it is uncertain whether adolescents are aware of the consequences of not adequately placing controls on their privacy settings. Guidelines would be helpful in safeguarding the privacy of account holders while providing physicians with the ethical means to seek information on these sites. Figure 3 demonstrates a guideline that may aid physicians in determining when it would be appropriate to seek SNS profiles.

Figure 3. Guideline on when to access social network site(SNS) profile.

Every patient has unique needs that need to be addressed, but risks, benefits, and ethics should be assessed. If patients are unable to communicate their needs to a physician due to intoxication or incapacitation, physicians must decide whether an SNS profile could help in understanding patient needs to improve patient care and outcomes. Although permission may not necessarily be granted, the ethical dilemma is one that must be weighed and judged by the physician with the best interests of the patient in mind.

CONCLUSION

During a period of observation of 4 hours, the patient received 3 liters of normal saline boluses, in addition to 2 doses of intravenous lorazepam and haloperidol. He eventually became more oriented and his restraints were removed.

The laboratory studies returned within normal range, and his urine drug screen was positive for benzodiazepines alone. Due to the information obtained from the patient’s public profile, concerns for intentional overdose and depression prompted urgent psychiatry consultation. Psychiatric evaluation revealed that the patient had a history of bipolar disorder, was noncompliant on treatment, and had a history of suicidal ideation one year prior. He also admitted to the psychiatrist that his girlfriend had betrayed him and confirmed current suicidal ideation after taking cyclobenzaprine pills, which he had not revealed to ED physicians. His vital signs remained stable and he continued to be asymptomatic during the remainder of his time in the ED. He was admitted to a psychiatric facility for suicidal ideation and was placed on his bipolar medications again.

SNS have become a controversial issue, as concerns for exposure to a hostile group of predators run rampant.1 However, we believe that there are benefits to adolescents using these sites not only for their own personal development,3,8 but also as a reference for the medical community. Our patient did not reveal many details of his at-risk behaviors on his profile, but these behaviors are prevalent in this age group and many of these activities are more openly displayed on blogs.2,9 The information our patient provided through his public profile led us to view his drug use in a more intentional rather than recreational light, and spurred a psychiatric evaluation that further revealed a depressed individual who was seeking dangerous avenues to take away the pain of betrayal. Our patient’s public profile led to his admission to a psychiatric facility for suicidal ideation. SNS can prove to be useful in situations where little information is available to healthcare practitioners and time is of the essence in determining the need for more than just supportive care.

Footnotes

Address for Correspondence: Vinodinee L Dissanayake, MD. Cook County Hospital, Department of Emergency Medicine, 1900 W Polk St, 10th Floor, Chicago, IL 60612. Email: venaccbh@gmail.com. 2 / 2014; 15:31 – 34

Submission history: Revision received February 10, 2013; Submitted June 12, 2013; Accepted June 21, 2013

Conflicts of Interest : By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. Pujazon-Zazik M, Park M. To tweet or not to tweet: gender differences and potential positive and negative health outcomes of adolescents’ social Internet use. Am J of Men’s Health. 2010;4(1):77–85.[PubMed]

2. Moreno M, VanderStoep A, Parks M, et al. Reducing at-risk adolescents’ display of risk behavior on a social networking web site. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(1):35–41. [PubMed]

3. Fullwood C, Sheehan N, Nicholls W. Blog function revisited: a content analysis of MySpace blogs. Cyberpsych and Beh. 2009;12(6):685–9. [PubMed]

4. Wilson K, Fornasier S, White K. Psychological predictors of young adults’ use of social networking sites. Cyberpsych and Beh. 2009;12(0):1–5.

5. Young S, Dutta D, Dommety G. Extrapolating psychological insights from Facebook profiles: a study of religion and relationship status. Cyberpsych and Beh. 2009;12(3):347–350. [PubMed]

6. Park N, Kee K, Valenzuela S. Facebook groups, uses and gratifications, and social outcomes. Cyberpsych and Beh. 2009;12(6):729–733. [PubMed]

7. Baker J, Moore S. Distress, coping and blogging: comparing new MySpace users by their intention to blog. Cyberpsych and Beh. 2008;11(1):81–85. [PubMed]

8. Berson IR, Berson MJ, Ferron JM. Emerging risks of violence in the digital age: Lessons for educators from an online study of adolescent females in the United States. J School Violence. 2002;1:51–71.

9. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Personal information of adolescents on the Internet: a quantitative content analysis of MySpace. J Adolesc. 2008;31(1):125–146. [PubMed]

10. Moreno M, Fost N, Christakis D. Research ethics in the MySpace era. Pediatrics. 2008;121:157–161.[PubMed]

11. Farmer A, Bruckner Holt C, Cook M, et al. Social networking sites: a novel portal for communication. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:455–459. [PubMed]

12. Lenhart A, Madden M, Macgill A, et al. Teens and social media. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project; 2007. [Last Accessed March 5, 2010]. Available at:http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2007/Teens-and-Social-Media.aspx.

13. Smyth J. Written emotional expression: effect sizes, outcome types, and moderating variables. J Consult Clin Psych. 1998;66:174–84. [PubMed]

14. Zeiger RB. Use of the journal in treatment of the seriously emotionally disturbed adolescent: a case study. Arts Psychother. 1994;21:197–204.

15. Burt CDB. Prospective and retrospective account making in diary entries: a model of anxiety reduction and avoidance. Anxiety Stress Coping. 1994;6:327–340.

16. Lepore S. Expressive writing moderates the relation between intrusive thoughts and depressive symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73:1030–1037. [PubMed]

17. L’Abate L. The use of writing in psychotherapy. Am J Psychother. 1991;45:87–98. [PubMed]

18. Myspace LLC, Privacy settings on Myspace: what you need to know. [Last Accessed June 10, 2013]. Available at: http://www.myspace.com/pages/privacysettings.

19. Myspace LLC, Myspace. [Last Accessed June 10, 2013]. Available at:http://www.myspace.com/my/settings/account/privacy.