| Author | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Tetsuji Suzuki, EMT | Graduate School of Health Information Science, Teikyo Heisei University, Department of Pre-hospital Emergency Medical Care |

| Masamichi Nishida, MD, PhD | Teikyo University, School of Medicine, Emergency Medicine |

| Yuriko Suzuki, RN | Kyoto Kujo Hospital, Department of Nursing |

| Kunio Kobayashi, MD, PhD | Graduate School of Health Information Science, Teikyo Heisei University, Department of Pre-hospital Emergency Medical Care |

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

Japan has a universal healthcare system, and this paper describes the reality of the healthcare services provided, as well as current issues with the system.

Methods:

Academic, government, and press reports on Japanese healthcare systems and healthcare guidelines were reviewed.

Results:

The universal healthcare system of Japan is considered internationally to be both low-cost and effective because the Japanese population enjoys good health status with a long life expectancy, while healthcare spending in Japan is below the average given by the Organization for Economic Corporation and Development (OECD). However, in many regions of Japan the existing healthcare resources are seriously inadequate, especially with regard to the number of physicians and other health professionals. Because healthcare is traditionally viewed as “sacred” work in Japan, healthcare professionals are expected to make large personal sacrifices. Also, public attitudes toward medical malpractice have changed in recent decades, and medical professionals are facing legal issues without experienced support of the government or legal professionals. Administrative response to the lack of resources and collaboration among communities are beginning, and more efficient control and management of the healthcare system is under consideration.

Conclusion:

The Japanese healthcare system needs to adopt an efficient medical control organization to ease the strain on existing healthcare professionals and to increase the number of physicians and other healthcare resources. Rather than continuing to depend on healthcare professionals being able and willing to make personal sacrifices, the government, the public and medical societies must cooperate and support changes in the healthcare system.

INTRODUCTION

While universal health insurance is commonly viewed in the United States (U.S.) as a means to guarantee adequate healthcare to all residents of the community, the system in Japan does not actually function this way. In fact, the Japanese healthcare system is breaking down rapidly. Offering inexpensive care equally to all citizens has depended on heavy individual sacrifices by healthcare professionals, especially pediatricians, obstetricians and gynecologists, and critical care/emergency care physicians. Doctors are exhausted and lack healthcare support and resources. Emergency and pre-hospital care systems are paying one of the heaviest tolls. Recent incidents, such as ambulances not being able to find hospitals with the appropriate resources to treat patients, are making national headlines.

In 2006 there were 8,943 hospitals (defined as a medical facility with 20 beds or more), with national or public hospitals accounting for 18.4%, and medical corporations (private entities) and private practice hospitals accounting for 70.5%. The number of clinics without inpatient facility (or 19 beds or less) was 98,609, while medical corporations and private practice accounted for the majority at 83.8%.1 Local clinics and hospitals serve as the primary emergency medical facility for treatment of minor cases; these local facilities also take turns attending to night-time and holiday duties. Larger hospitals and university hospitals, regardless of whether privately or publicly owned, are responsible for providing secondary or tertiary emergency medical care.

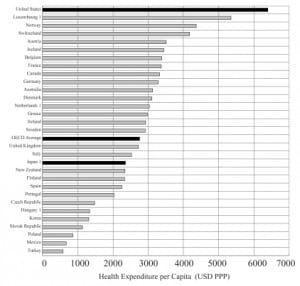

The Fatigue of Healthcare Professionals

Shortages of physicians in all specialties are apparent. According to a report by the OECD released in July 2007, the number of physicians per 1,000 people is two; this ratio is among the lowest in industrialized countries and below the 30-member OECD average of three.2 In the same 2007 OECD report, health expenditures as a share of GDP was reported to be 8% in Japan during the year of 2004, which is also below the 9% OECD average, while in the United States 15.3% was spent on healthcare in 2005. Health expenditure per capita was reported as $2,358 for Japan, $2,753 for the OECD average, and $6,401 for the United States (Figure 1). Therefore, the number of healthcare professionals and the amount spent on healthcare are possibly the lowest of the G7 nations (United States, Japan, Germany, France, United Kingdom, Italy, and Canada).

Nurses are chronically in short supply. In most hospitals the ratio of the number of nurses to patients is more than 10 to 1. The Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare is proposing a 7 to 1 ratio in 60% of hospitals with 300 beds or more by 2009. However, with this ratio the shortage of nurses is expected to be 70,000 by April 2008.3

On the other hand, the number of licensed paramedics in Japan is increasing. According to April 2007 data published by the Fire and Disaster Management Agency, there are 20,059 licensed paramedics in Japan, 99.9% of fire stations have in-house paramedics, and of 4,940 emergency response teams, 4,201 have licensed paramedics.4 Japan has a state-of-the-art emergency communication system with highly equipped ambulances. Because Japan is geographically small, the average arrival time for an ambulance is 6.5 minutes. Therefore, paramedics arriving at the site is not considered to be a healthcare issue.

Overall the Japanese population enjoys a very long life expectancy (82 years for the entire population) and an extremely low infant mortality rate of 2.8 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2005 close to half of the OECD average.2 Interestingly, Japan has the highest number of doctor consultations per capita of 13.8; Japanese people visit a healthcare facility on average almost 14 times a year, while the OECD average is 6.5 times, and the U.S. average is 3.9 times.2 In the Japanese medical system, this number of visits is considered acceptable, despite the low number of practicing physicians per population of 1000 (two in Japan, 2.4 in the U.S., and more than three in many European countries).2

Many factors, such as genetics, diet, culture and technology, can account for the seemingly good health of the Japanese. Despite those favorable circumstances, only so much can be done in terms of serious diseases or injuries. The greatest contributing factor by far is that the Japanese healthcare system depends on physicians and healthcare professionals making many personal sacrifices. These individuals work long hours, often without either documentation of or compensation for overtime. According to a 2006 survey of 3,388 medical doctors by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japanese physicians worked 66.4 (±18.0) hours/week, with the maximum reported at 152.5 hours, and physicians younger than 30 years old worked an average of 77.3 hours/week.5 While U.S. physicians receive an annual compensation of $150,000 to $300,000,6 the average compensation for Japanese physicians was about $104,000 for those in their early forties and $77,000 for those in their mid-thirties.7

Traditionally because the Japanese public has viewed working in healthcare professions as “sacred,” sacrificing personal time and pleasure was expected. This cultural attitude has been used by many public hospitals as a reason to limit the labor rights of their physicians, who have been unable to organize strikes or protest for higher wages or shorter hours. Times have changed, and the Japanese healthcare system is no longer exempt from legal and patient issues. Malpractice lawsuits are on the rise, healthcare spending by government is decreasing, and patient expectations have increased. These factors, along with the increased availability of information through the media and the Internet, are contributing to a change in public attitude toward healthcare.

Old Values Have Led to System Issues

When faced with physician shortages, other countries have delegated various jobs to other qualified healthcare professionals, such as nurses, pharmacists or medical technicians. Such delegation is a new concept in the Japanese medical systems. In Japan healthcare professionals, especially physicians, are granted high levels of authority; others refrain from assisting because the act of helping the physician is perceived as an insult to the physician’s ability and knowledge and as an invasion of the medical profession.

With the shortage of physicians and of interaction between professionals, training other technicians for job delegation becomes especially difficult. In addition, there are not enough emergency care physicians to train emergency medical technicians (EMTs), who could possibly become leaders in the field. This is compounded by the fact that EMTs have a relatively low public status in Japan compared with their situation in other developed nations. In turn, this low level of respect leads to low motivation and to lack of leaders and role models. More public awareness of the importance of the role of EMTs and a publicity effort may be needed. Although most EMTs in Japan are stationed at fire departments, in 1991 the official role and regulation of paramedics in Japan was established via a national licensing system. Five years of working experience as ambulance staff, more than 500 hours of lecture, and more than 400 hours of hospital training or simulation in a training facility are required to become an EMT in Japan. However, unlike in the EMT system of the U.S., in Japan there is only one level of EMT, and on-the-job training or continuing education is not required.8

The Nara Incidents

On August 7, 2006, a mother in the delivery room of Oyodo Hospital in the southern part of Nara prefecture became unconscious. The attending doctor diagnosed eclampsia and contacted the Nara Medical University Hospital. The facility refused the patient because no bed was available. Other hospitals were also contacted, but none could accommodate the patient. Finally, the National Cardiovascular Center in Osaka prefecture accepted the patient, and she was diagnosed with cerebral hemorrhage. An emergency operation and cesarean section was performed, but the mother died about a week later. The family sued Oyodo Hospital for civil damages.9

In the same Nara prefecture about a year later, a pregnant woman called an ambulance because of abdominal pain early in the morning of August 29, 2007. Nine hospitals refused the patient because of insufficient resources. The woman was not under prenatal care and had a history of miscarriage; she delivered a stillborn child before eventually arriving at Takatsuki Hospital in Osaka.10

Media reaction further aggravated the local situation, forcing Oyodo hospital to close its obstetrics/gynecology department indefinitely, despite the fact that investigators concluded that making a diagnosis of cerebral hemorrhage was difficult in the situation, and no criminal case was established.10 The Oyodo case captured tremendous media attention and became one of the causes of a national trend in physicians leaving regional or public hospitals. Some physicians can afford to leave the hospital in favor of solo private practices, while others simply resign their hospital position for part-time or temporary work at other hospitals or clinics. The physician author Hideki Komatsu coined a phrase “tachisarigata sabotage,” which means “sabotage by leaving.”11 This expression is an apt description of how hospitals are losing already scarce doctors.

The shortage of physicians in emergency medicine is especially critical, as reported from a survey in the Fukuoka prefecture conducted by Ezaki et al.12 Fukuoka prefecture is home to the city of Fukuoka, one of Japan’s major urban centers, and an industrial area with the nation’s ninth largest population – approximately five million as of 2006. Despite an adequate social and economic infrastructure, only 24.4% (32 out of 131) of its emergency medicine facilities responding to a survey had emergency medicine specialists or acute care physicians. Most other facilities were attended by non-emergency or acute care physicians with certifications from organizations, such as the Japan Surgical Society or Japan Society of Internal Medicine.

More Patient Issues

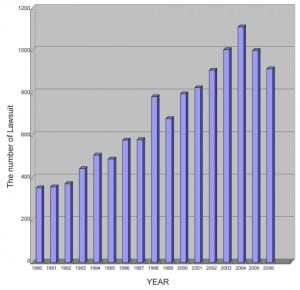

The Japanese healthcare system traditionally does not feature a family doctor or primary care physician, and insurance providers allow patients to see specialists directly without the need for a referral. Most hospitals and clinics routinely accept walk-in patients who usually must wait for long periods of time to see a doctor. One result is that specialists must spend time seeing minor cases that do not require specialist care. For instance, a patient with red eyes goes directly to an ophthalmologist in a university hospital when only minor treatment is needed for mild conjunctivitis. This lack of an organized primary care system overwhelms Japan’s limited medical resources. Some facilities are starting to adopt booking systems to manage appointments with doctors. However, when a fully booked schedule causes a patient to be turned away, the Japanese public views this as impersonal and immoral because healthcare professionals are supposed to help people in need whenever asked. Therefore, the facilities using appointment systems usually must accept walk-ins as well, making the appointment system essentially meaningless. This idea stems from the same misconception that the arrival of an ambulance automatically guarantees medical care. The idea that health and safety is guaranteed in Japan has created another issue—that of the so-called “monster patient,” who makes unreasonable demands of healthcare professionals. Some patients demand that medicine be perfect and that medical care should always cure the disease. Of course, in reality, this is impossible. The rise in the number of medical malpractice suits in recent years shows that the attitude of Japanese patients toward the healthcare profession has certainly changed, and it is being reflected in the rise of malpractice suits. During the mid 1980s to the early 1990s, the number of new medical malpractice suits in all of Japan numbered in the three hundreds. However, during the late 1990s to early 2000s, the number increased rapidly (Figure 2) while the total number of all civil cases remained at about 150,000 in Japan.13,14 In the past few years, the effort to obtain informed consent from patients and families may be contributing to a leveling off in the number of new malpractice lawsuits. However, the psychological barrier that had inhibited lawsuits against a physician who does a sacred job has clearly been lowered. Despite such change in public attitudes, the Japanese legal system has not yet developed a method of properly judging medical fault versus unreasonable demand or expectation; in other words, the legal system is not currently prepared to make decisions in medical cases.

Another issue highlighted by the Nara cases is that many medical facilities are reluctant to establish emergency care systems in obstetrics because they have only half the necessary number of doctors, and therefore, accommodating emergency cases will likely lead to malpractice suits.15

Recent Responses from the Japanese Administration

One positive result from the Nara incidents and other issues was a response from government and prefectural administrations that ordered the prefectures to improve transportation systems. Japan has been reducing its number of physicians since the 1980s, in an effort to limit healthcare costs. This policy is now being reconsidered, and Yoichi Masuzoe, Minister of Health, Welfare and Labor, announced the formation of a study group on solving various healthcare-related issues, such as the insufficient number of physicians and regional differences in the level of healthcare.16 This group will consider inviting foreign physicians to practice under certain agreements and mandating medical school graduates to work in rural regions. The prefectural governors are asking the group to identify ways to increase the number of medical school admissions, to delegate some of the work currently being performed by doctors to registered nurses, and to educate primary care physicians to practice at a local level.

In the Nara prefecture the governor of Nara, Shougo Araki, is leading the “Nara Prefecture Board Meeting of A Survey on Issues in Emergency Transportation of Pregnant Women” and implementing a plan to assign a “high-risk pregnant women transport coordinator” system, as well as a network of private practitioners to take turns handling emergency on-call duties. The prefecture started simulation trainings for transport coordinators in November 2007, and four coordinators were assigned for weekends and holiday duties at Nara Prefectural Medical College Hospital as of November 27, 2007.17The Board published an emergency response manual for these services, emphasizing the importance of sharing critical patient information between paramedics and hospitals.18The Board also intends to create a seamless system through collaboration of emergency personnel, hospital personnel, and other medical professionals. The need for medical control of emergency and pre-hospital care should be reemphasized throughout.

Introduction of True Medical Control and Medical Director as a Solution

The proposed coordinator system is considered adjunctive to medical control of pre-hospital care. Currently in the Japanese emergency department (ED), physicians working in the ED are the ones making decisions on either to accept or refuse the arrival of patients by ambulance.19 Both public and healthcare professionals hope this new system would eliminate situations in which ED physicians refuse ambulance arrival without recognizing the severity of the case or knowing the availability of beds in the hospital. In Japan the medical control of pre-hospital care is defined as ensuring the quality of medical activities by having physicians instruct, advise, or evaluate the medical activities of paramedics during transport of patients from incident sites to medical facilities.20

The idea for medical control of emergency and pre-hospital care is relatively new in Japan. It was brought into focus by a 1998 Ministry of Health report on the study of the pre-hospital care situation in various regions of the U.S.21 and by two other Japanese reports, namely, a 2000 report from a study group on the future of the emergency service system, Ministry of Welfare, and a 2001 report from a study group on promoting advancement of emergency services of the Fire and Disaster Management Agency (FDMA).

Despite the fact that the study groups did not provide specific recommendations on changing the emergency service system in Japan, they emphasized collaboration among prefectures, regardless of differences in prefectural administrations, as well as collaboration between physicians and the FDMA, which most Japanese paramedics belong to. The groups were generally optimistic that developing and implementing such a system could be realized, especially considering the current level of medical technology and the expertise of the FDMA. In fact, the Tokyo metropolitan area has established a medical control system in which the efforts of administration, the fire department, and local emergency medicine physicians have been coordinated to function as one group.22

A proposed next step would be to support the creation and development of a role for a medical director. This individual would oversee the entire operation and improve its efficiency while ensuring the quality of healthcare and transport activities. Within Japan’s current medical control system, emergency care physicians have neither the authority to assign or terminate personnel nor the power to make decisions on how local programs should continue. The Japan Society of Emergency Medicine and other researchers in emergency medicine are currently studying the U.S. system of emergency medical services, especially the activities and achievements of the National Association of EMS Physicians.23

Implementing a system in Japan that is similar to that of the United States would certainly have some difficulties. For example, the Japanese administration would first need to define the role and responsibilities of a medical director, and then establish standardized programs and educational courses at the national level for medical directors. However, it can be done—the medical associations in the United States showed strong leadership to establish and maintain such programs, and a similar effort is needed in Japan to develop and implement a more coordinated and higher quality system.

LIMITATIONS

The subject of this article is topical, and comparison to other nations or systems is difficult because of differing cultural and economic backgrounds.

CONCLUSION

Serious issues in the Japanese healthcare system need immediate attention. Adopting an efficient medical control system is needed to ease the strain on existing healthcare professionals and to increase the number of physicians and amount of resources. Cooperation and support from the government, the public and medical societies are essential. When contemplating universal healthcare and finding the best method of pre-hospital and emergency care and transport, other nations should heed the current status of the healthcare situation in Japan as an example.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Tareg Bey, MD

Submission history: Submitted December 12, 2007; Revision Received March 13, 2008; Accepted March 14, 2008

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Address for correspondence: Tetsuji Suzuki, EMT. Department of Pre-hospital Emergency Medical Care, Graduate School of Health Information Science, Teikyo Heisei University, 2-51-4 Higashi-Ikebukuro, Toshimaku, Tokyo 170-8445 Japan

Email: cpr119@coral.ocn.ne.jp

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources, and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none.

REFERENCES

1. The Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Ministerial Secretariat Statistical Information Department. Status (and Trends) of Medical Facility Survey 2006. 2006.

2. Organization for Economic Corporation and Development (OECD) Health Data. [Accessed March 11, 2008];2007 Available at:http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/45/51/38979974.pdf.

3. Japan Medical Association. Report on Supply and Demand of Nursing Staffs – October 2006 Survey (Rapid Report). January 17, 2007.

4. Ministry of Internal Affaires and Communications, Fire and Disaster Management Agency. Overview of Emergency Medical Response during 2006. September 7, 2007.

5. The Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare report on “Survey on Working Status of Medical Doctors in relation to Medical Doctor Supply and Demand.” [Accessed February 2, 2008]; Available at: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/shingi/2006/02/s0208-12b.html.

6. U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Outlook Handbook, Physicians and Surgeons. [Accessed February 2, 2008]; Available at:http://www.bls.gov/oco/ocos074.htm.

7. Japan Medical Association Scheduled Brief on “Responses to the Survey on Wages Basic Statistical Report.” [Accessed as February 2, 2008];2007 April 12; Available at:http;//www.med.or.jp/teireikaiken.

8. Shigeta M, Maeda K. Kyukyutaiin to Kyukyu kyumeishi kyoiku (ambulance crew and paramedic education) Rinsho to Kyoiku (Clinical Activities and Education) 2000;77(8)

9. Death of pregnant woman in Nara, the family sues for malpractice. [Accessed May 29 2007];Asahi Shinbun. 2007 May 23; Available at:http://www.asahi.com/national/update/0523/OSK200705230082.html.

10. Tragedy of pregnant woman again, miscarriage during emergency transport. [Accessed November 25, 2007];Yomiuri Shinbun. 2007 August 29; Available at:http;//Osaka.yomiuri.co.jp/mama/tokushu1/mt20070830kk05.htm.

11. Komatsu H. Iryou Houkai Tachisarigata Sabotage (Crisis in Medicine – Sabotage by Leaving) Tokyo, Japan: Asahi Shinbun Sha; 2006.

12. Ezaki T, Yamada T, Yasuda M, Kanna T, Shiraishi K, Hashizume M. Current status of Japanese emergency medicine based on a cross-sectional survey of one prefecture. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19:523–527. [PubMed]

13. Hojyo M. Medical Malpractice and Measures for Safety in Medicine, Shakai Hoken Jyunpo, No.2202. Medical and Legal Research Association; Tokyo: 2004. [Accessed March 11, 2008]. Available at: http://www.m-l.or.jp/research/media040321.htm.

14. Supreme Court of Japan. Medical related suits processing status and average time for trial time. [Accessed January 29, 2008]; Available at:http://www.courts.go.jp/saikosai/about/iinkai/izikankei/toukei_01.html.

15. Outline of Nara Prefecture Board Meeting of Survey on Issues in August 2007 Emergency Transportation of Pregnant Women Incident. Prefecture of Nara. 2007

16. Measure to the lack of physicians. Forming study group by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. [Accessed November 26, 2007];Asahi Shinbun. 2007 Available at:http://www.asahi.com/life/update/1126/TKY200711260159.html.

17. Dispatch training using phone, coordinators and thirty other staffs joined. [Accessed November 27, 2007];Nara Shinbun. 2007 Available at: http://www.nara-np.co.jp/n_all/071127/all071127b.shtml.

18. Place coordinator within this month – prefectural survey group submits final report. [Accessed November 25, 2007];Nara Shinbun. 2007 Available at: http://www.nara-np.co.jp/n_all/071110/all071110b.shtml.

19. O’Malley RN, O’Malley GF, Ochi G. Emergency medicine in Japan. Ann Emerg Med.2001;38:441–446. [PubMed]

20. Japan Society of Emergency Medicine. Pre-hospital care and medical control. Edited by Study group of medical control system: Igakushoinn; Tokyo, Japan. 2005. p. 19.

21. Heisei Ten Scientific report and study result report of the Ministry of Welfare. 1998. Survey on pre-hospital care situation in various United States locations.

22. Yokoyama M. Collaboration with emergency life-saving technicians and medical doctors, developed by medical control. Jpn J Acute Med. 2006;30:383–389.

23. Guide for Preparing Medical Directors. American College of Emergency Physicians. [Accessed Nov 28, 2007];National Association of EMS Physicians. Available at:http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/ems/2001GuideMedical.pdf.